15. മാപ്പിള ലഹളയെ വിശാലമായൊന്ന് നോക്കിയാൽ

15. മാപ്പിള ലഹളയെ വിശാലമായൊന്ന് നോക്കിയാൽ

Last edited by VED on Mon Jun 30, 2025 6:07 pm, edited 6 times in total.

Contents

c #

1. ഇരുപക്ഷത്തും തീകൊളുത്തി നടുവിൽ പിടിച്ചു നിൽക്കേണ്ടി വന്നവരെക്കുറിച്ച്

2. ഹിന്ദി ഇംപീരിയലിസത്തിന് കൂറ് കാണിക്കുന്നത് സ്വാതന്ത്ര്യമാവുന്നത്

3. എഴുത്തിന്റെല ഒഴുക്കിലേക്ക് വീണ്ടും

4. ഹിന്ദുക്കളും ഇസ്ലാം മതവിശ്വാസികളും അന്ന്

5. പൊതുശത്രുവിനെ കാണിച്ചുകൊടുക്കാൻ ആയാൽ

6. സമൂഹത്തിൽ സ്ഫോടനാത്മകമായ സാമൂഹിക യന്ത്രകാരകപ്രവർത്തനം

7. പരസ്പരവിരുദ്ധങ്ങളായ വിവരത്തുണ്ടുകളിൽ നിന്നും മനസ്സിലാക്കാവുന്നത്

8. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കമ്പനി, ഭരണം നേരിട്ടെടുത്തതിനെക്കുറിച്ച്

9. ഏതോ ഒരു അസഹനീയമായ നിഷ്ഠൂരവാഴ്ചയുടെ സൂചന

10. വാക്ക് കോഡുകളിൽ തരംതാഴ്ത്തിക്കൊണ്ടുള്ള ഏറ്റുമുട്ടൽ

11. പന്തല്ലൂർ കുന്നിൽ നിന്നും 15 മൈൽ വൃത്തപരിധിക്കുള്ളിൽ

12. ഹൈന്ദവ - മാപ്പിള വർഗ്ഗീയ ഭാവത്തിന്റെs പിന്നാമ്പുറം

13. ഒരു രോഗബാധപോലെ നിലനിന്നിരുന്ന ഒരു മാനസികഭാവം

14. ഞങ്ങളാണ് ഇസ്ലാമിന്റെന സംരക്ഷകർ എന്ന ഭാവം

15. കോപാവേശത്തെ മതഭ്രാന്തുമായി കൂട്ടിക്കുഴച്ച് ഓടി അടുക്കുന്നവർ

16. ചിന്തകളിൽ മാറാല വല പോലുള്ള അദൃശമായ പല മാനസിക പിടിവലികളും വളർത്തുന്ന ഭാഷ

17. അന്നത്തെ ഉന്നത ജനങ്ങളുടെ വീക്ഷണ കോണിലൂടെ

18. മലബാറിലെ വ്യത്യസ്തരായ മാപ്പിളമാരും, അവരോരുത്തരെക്കുറിച്ചുമുള്ള വ്യത്യസ്തമായ കാഴ്ചപ്പാടും

19. വൻ പോക്കിരിയുടെ സ്വഭാവഗുണം

20. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണ പക്ഷത്തിന്റെr മാനസിക നിലവാരത്തിൽ നിന്നും വ്യത്യസ്തമായ കാര്യങ്ങൾ

21. പ്രാദേശിക ഉന്നതരെ രണ്ടു വ്യത്യസ്ത രീതിയികളിൽ കണ്ടിരിക്കാം

22. വെറും വാക്കുകളിലൂടെ പാറക്കല്ലിന്റെ= ഭാരം ഏറ്റുവാങ്ങേണ്ടിവരുന്നതിനെക്കുറിച്ച്

23. ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷ ഉദ്ദേശ്യ ലക്ഷ്യ പ്രവർത്തനങ്ങളിൽ പങ്ക് ചേർന്നുപോയതിനെക്കുറിച്ച്

24. സമൂഹത്തെ ഒരു പൊട്ടിത്തെറിയിലേക്ക് കൊണ്ടെത്തിച്ച സാമൂഹിക പരിഷ്ക്കരണം

25. തിരുത്തൽ വരുത്താൻ പാതകളില്ലാത്ത ദുഷ്ട നാട്ടുനടുപ്പുകളും കീഴ്വഴക്കങ്ങളും

26. വാസ്തവം പറയാൻ ആർക്കും താൽപ്പര്യം ഇല്ലാത്തത്

27. അസഹ്യമായി തോന്നാവുന്ന സാധാരണ സാമൂഹിക യാഥാർത്ഥ്യം

28. സാമൂഹിക തകിടം മറിച്ചിടലിനേക്കാൾ ഭയാനകമായ ഒരു കാര്യം

29. യാതോരു ലാഭേച്ചയും ഇല്ലാതെ നടപ്പിൽ വരുത്തിയ കാര്യം

30. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭാഷയുടെ യാതോരു പരിസരസ്വാധീനവും ഇല്ലാത്ത അടിമത്തം

31. അടിമത്തം ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭാഷാ പരിസരാന്തരീക്ഷത്തിൽ

32. അടിമത്തത്തെ നിലനിർത്താൻ താൽപ്പര്യപ്പെടുന്ന നാട്ടിൽ അടിമത്തം തുടച്ചുനീക്കിയത്

33. സാമൂഹീക ഘടനയും സാമൂഹിക ആശയവിനിമയ പാതകളും നിശ്ചയിക്കുന്നത് ഭാഷയാണ്

34. ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥർ ആയാൽ സാമൂഹിക ബലം ലഭിക്കും എന്ന കണ്ടെത്തൽ

35. പുതിയ വ്യക്തിത്വത്തിന് നിരക്കാത്ത സാമൂഹികവും ഭാഷാപരവും ആയ അനുഭവങ്ങൾ

36. സ്വന്തം പാരമ്പര്യ ആത്മീയ പ്രസ്ഥാനം അന്യാധീനപ്പെടുന്നത് കണ്ടുനിന്നവർ

37. ഇങ്ഗ്ളണ്ടിൽ നിലനിൽക്കുന്ന ഗുരുതരമായ പിശകുകളും പരിമിതികളും

38. എതിർകോണുകളിൽ നിലകൊള്ളുന്ന മൃഗീയത

39. ഉന്നതർ പാപ്പരായാൽ, വീടിന് പുറത്ത് ഇറങ്ങാൻ പോലും പറ്റാത്ത തരത്തിലുള്ള ഭാഷാ പ്രസ്ഥാനം

40. തുടച്ചുനീക്കപ്പെട്ട കൊള്ളയടി പ്രസ്ഥാനത്തിന്റെw തിരിച്ചുവരവ്

41. വൻ നിലവാരത്തിലുള്ള മാനസിക പരിശീലനം ലഭിച്ചതിനെക്കുറിച്ച്

42. വിവരം ലഭിച്ചാൽ മാഞ്ഞുപോകുന്ന ഒരു മതിപ്പ്

43. ജനങ്ങളുടെ ഭാഷാപരമായ സംസ്ക്കാരത്തിന് അനുസൃതമായിട്ടായിരിക്കും, അവരുടെ വാണിജ്യപ്രസ്ഥാനങ്ങളുടെ സ്വഭാവം

44. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണം ബൃട്ടിഷ്-ഇന്ത്യയിൽ കൊണ്ടുവന്ന മഹത്തായ കാര്യങ്ങളെ എണ്ണിപ്പറയാം

45. English East India Company ഭരണം British-Indiaയിൽ തുടങ്ങിവച്ച വിദ്യാഭ്യാസ പ്രസ്ഥാനങ്ങളുടെ ഒരു തലക്കെട്ട് ലിസ്റ്റ്

46. ജനങ്ങൾ നിത്യവും അനുഭവിച്ച ദുരിതങ്ങൾക്ക് ഒരു അന്ത്യം കണ്ടുതുടങ്ങിയത്

47. മൂല്യചോഷണത്തിന് എതിരായുള്ള ഒരു വൻമതിലായി നിലനിന്നിരുന്നത്

48. പലവിധ എതിർപ്പുകളേയും നേരിട്ടുകൊണ്ട് തന്നെ പല ക്ഷേമരാഷ്ട്ര പദ്ധതികൾക്കും തുടക്കമിട്ടത്

49. മാപ്പിളമാരിലെ പാരമ്പര്യ ഉന്നത കൂട്ടർ അന്ധാളിച്ചു നിന്നിരുന്നതിനെക്കുറിച്ച്

50. മാപ്പിള ലഹളയ്ക്ക് പിന്നണിയിൽ നിലനിന്ന സാമൂഹിക സങ്കീർണ്ണതകൾ

1. ഇരുപക്ഷത്തും തീകൊളുത്തി നടുവിൽ പിടിച്ചു നിൽക്കേണ്ടി വന്നവരെക്കുറിച്ച്

2. ഹിന്ദി ഇംപീരിയലിസത്തിന് കൂറ് കാണിക്കുന്നത് സ്വാതന്ത്ര്യമാവുന്നത്

3. എഴുത്തിന്റെല ഒഴുക്കിലേക്ക് വീണ്ടും

4. ഹിന്ദുക്കളും ഇസ്ലാം മതവിശ്വാസികളും അന്ന്

5. പൊതുശത്രുവിനെ കാണിച്ചുകൊടുക്കാൻ ആയാൽ

6. സമൂഹത്തിൽ സ്ഫോടനാത്മകമായ സാമൂഹിക യന്ത്രകാരകപ്രവർത്തനം

7. പരസ്പരവിരുദ്ധങ്ങളായ വിവരത്തുണ്ടുകളിൽ നിന്നും മനസ്സിലാക്കാവുന്നത്

8. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കമ്പനി, ഭരണം നേരിട്ടെടുത്തതിനെക്കുറിച്ച്

9. ഏതോ ഒരു അസഹനീയമായ നിഷ്ഠൂരവാഴ്ചയുടെ സൂചന

10. വാക്ക് കോഡുകളിൽ തരംതാഴ്ത്തിക്കൊണ്ടുള്ള ഏറ്റുമുട്ടൽ

11. പന്തല്ലൂർ കുന്നിൽ നിന്നും 15 മൈൽ വൃത്തപരിധിക്കുള്ളിൽ

12. ഹൈന്ദവ - മാപ്പിള വർഗ്ഗീയ ഭാവത്തിന്റെs പിന്നാമ്പുറം

13. ഒരു രോഗബാധപോലെ നിലനിന്നിരുന്ന ഒരു മാനസികഭാവം

14. ഞങ്ങളാണ് ഇസ്ലാമിന്റെന സംരക്ഷകർ എന്ന ഭാവം

15. കോപാവേശത്തെ മതഭ്രാന്തുമായി കൂട്ടിക്കുഴച്ച് ഓടി അടുക്കുന്നവർ

16. ചിന്തകളിൽ മാറാല വല പോലുള്ള അദൃശമായ പല മാനസിക പിടിവലികളും വളർത്തുന്ന ഭാഷ

17. അന്നത്തെ ഉന്നത ജനങ്ങളുടെ വീക്ഷണ കോണിലൂടെ

18. മലബാറിലെ വ്യത്യസ്തരായ മാപ്പിളമാരും, അവരോരുത്തരെക്കുറിച്ചുമുള്ള വ്യത്യസ്തമായ കാഴ്ചപ്പാടും

19. വൻ പോക്കിരിയുടെ സ്വഭാവഗുണം

20. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണ പക്ഷത്തിന്റെr മാനസിക നിലവാരത്തിൽ നിന്നും വ്യത്യസ്തമായ കാര്യങ്ങൾ

21. പ്രാദേശിക ഉന്നതരെ രണ്ടു വ്യത്യസ്ത രീതിയികളിൽ കണ്ടിരിക്കാം

22. വെറും വാക്കുകളിലൂടെ പാറക്കല്ലിന്റെ= ഭാരം ഏറ്റുവാങ്ങേണ്ടിവരുന്നതിനെക്കുറിച്ച്

23. ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷ ഉദ്ദേശ്യ ലക്ഷ്യ പ്രവർത്തനങ്ങളിൽ പങ്ക് ചേർന്നുപോയതിനെക്കുറിച്ച്

24. സമൂഹത്തെ ഒരു പൊട്ടിത്തെറിയിലേക്ക് കൊണ്ടെത്തിച്ച സാമൂഹിക പരിഷ്ക്കരണം

25. തിരുത്തൽ വരുത്താൻ പാതകളില്ലാത്ത ദുഷ്ട നാട്ടുനടുപ്പുകളും കീഴ്വഴക്കങ്ങളും

26. വാസ്തവം പറയാൻ ആർക്കും താൽപ്പര്യം ഇല്ലാത്തത്

27. അസഹ്യമായി തോന്നാവുന്ന സാധാരണ സാമൂഹിക യാഥാർത്ഥ്യം

28. സാമൂഹിക തകിടം മറിച്ചിടലിനേക്കാൾ ഭയാനകമായ ഒരു കാര്യം

29. യാതോരു ലാഭേച്ചയും ഇല്ലാതെ നടപ്പിൽ വരുത്തിയ കാര്യം

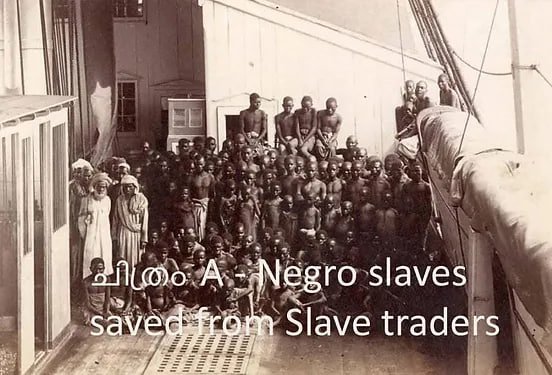

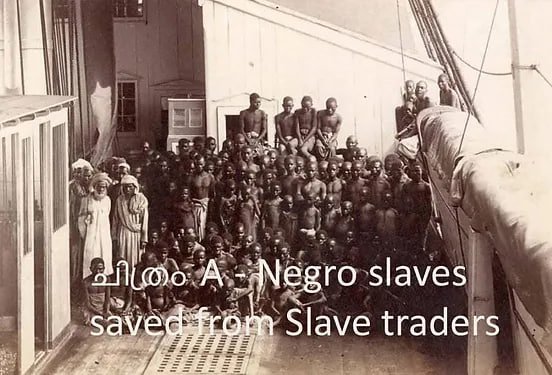

30. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭാഷയുടെ യാതോരു പരിസരസ്വാധീനവും ഇല്ലാത്ത അടിമത്തം

31. അടിമത്തം ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭാഷാ പരിസരാന്തരീക്ഷത്തിൽ

32. അടിമത്തത്തെ നിലനിർത്താൻ താൽപ്പര്യപ്പെടുന്ന നാട്ടിൽ അടിമത്തം തുടച്ചുനീക്കിയത്

33. സാമൂഹീക ഘടനയും സാമൂഹിക ആശയവിനിമയ പാതകളും നിശ്ചയിക്കുന്നത് ഭാഷയാണ്

34. ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥർ ആയാൽ സാമൂഹിക ബലം ലഭിക്കും എന്ന കണ്ടെത്തൽ

35. പുതിയ വ്യക്തിത്വത്തിന് നിരക്കാത്ത സാമൂഹികവും ഭാഷാപരവും ആയ അനുഭവങ്ങൾ

36. സ്വന്തം പാരമ്പര്യ ആത്മീയ പ്രസ്ഥാനം അന്യാധീനപ്പെടുന്നത് കണ്ടുനിന്നവർ

37. ഇങ്ഗ്ളണ്ടിൽ നിലനിൽക്കുന്ന ഗുരുതരമായ പിശകുകളും പരിമിതികളും

38. എതിർകോണുകളിൽ നിലകൊള്ളുന്ന മൃഗീയത

39. ഉന്നതർ പാപ്പരായാൽ, വീടിന് പുറത്ത് ഇറങ്ങാൻ പോലും പറ്റാത്ത തരത്തിലുള്ള ഭാഷാ പ്രസ്ഥാനം

40. തുടച്ചുനീക്കപ്പെട്ട കൊള്ളയടി പ്രസ്ഥാനത്തിന്റെw തിരിച്ചുവരവ്

41. വൻ നിലവാരത്തിലുള്ള മാനസിക പരിശീലനം ലഭിച്ചതിനെക്കുറിച്ച്

42. വിവരം ലഭിച്ചാൽ മാഞ്ഞുപോകുന്ന ഒരു മതിപ്പ്

43. ജനങ്ങളുടെ ഭാഷാപരമായ സംസ്ക്കാരത്തിന് അനുസൃതമായിട്ടായിരിക്കും, അവരുടെ വാണിജ്യപ്രസ്ഥാനങ്ങളുടെ സ്വഭാവം

44. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണം ബൃട്ടിഷ്-ഇന്ത്യയിൽ കൊണ്ടുവന്ന മഹത്തായ കാര്യങ്ങളെ എണ്ണിപ്പറയാം

45. English East India Company ഭരണം British-Indiaയിൽ തുടങ്ങിവച്ച വിദ്യാഭ്യാസ പ്രസ്ഥാനങ്ങളുടെ ഒരു തലക്കെട്ട് ലിസ്റ്റ്

46. ജനങ്ങൾ നിത്യവും അനുഭവിച്ച ദുരിതങ്ങൾക്ക് ഒരു അന്ത്യം കണ്ടുതുടങ്ങിയത്

47. മൂല്യചോഷണത്തിന് എതിരായുള്ള ഒരു വൻമതിലായി നിലനിന്നിരുന്നത്

48. പലവിധ എതിർപ്പുകളേയും നേരിട്ടുകൊണ്ട് തന്നെ പല ക്ഷേമരാഷ്ട്ര പദ്ധതികൾക്കും തുടക്കമിട്ടത്

49. മാപ്പിളമാരിലെ പാരമ്പര്യ ഉന്നത കൂട്ടർ അന്ധാളിച്ചു നിന്നിരുന്നതിനെക്കുറിച്ച്

50. മാപ്പിള ലഹളയ്ക്ക് പിന്നണിയിൽ നിലനിന്ന സാമൂഹിക സങ്കീർണ്ണതകൾ

Last edited by VED on Mon Jun 16, 2025 11:03 am, edited 13 times in total.

1. ഇരുപക്ഷത്തും തീകൊളുത്തി നടുവിൽ പിടിച്ചു നിൽക്കേണ്ടി വന്നവരെക്കുറിച്ച്

ഇന്ത്യയിൽ ചരിത്ര എഴുത്ത് ഇന്ന് നിലവിൽ ഉള്ള ഇന്ത്യയെന്ന രാജ്യത്തിനെ കേന്ദ്രീകരിച്ചുകൊണ്ടാണ് നടക്കുന്നത്. ഈ വിധം ആപേക്ഷികമായി എന്തും എഴുതാം.

ഉദാഹരണത്തിന്, പ്രപഞ്ചത്തിന്റെ മധ്യത്തിലാണ് നാം ഇരിക്കുന്നത് എന്ന ഭാവത്തിൽ പ്രപഞ്ചത്തിലെ മറ്റെല്ലാ വസ്തുക്കളേയും അവയുടെ നീക്കങ്ങളേയും അവയുടെ വേഗതേയും മറ്റും നമുക്ക് ആപേക്ഷികമായി അളക്കാനും വ്യാഖ്യാനിക്കാനും ആവും.

എന്നാൽ നമുക്ക് ലഭിക്കുന്ന എല്ലാവിവരങ്ങളും ഭൂമിയെന്ന Frame of referenceസിനുള്ളിൽ (ചട്ടക്കൂടിനുള്ളിൽ നിന്നുമുള്ള വീക്ഷണകോണിൽനിന്നും) മാത്രം സത്യമാകുന്ന കാര്യങ്ങൾ ആയേക്കാം. ഭൂമിയെ ഒന്ന് പിടിവിട്ടുകൊണ്ട് നീങ്ങിയാൽ, നമുക്ക് ലഭിച്ച എല്ലാ അളവുകളും ദിശകളും വേഗതകളും മറ്റും അർത്ഥശൂന്യമായിപ്പോകും.

അതേ പോലൊക്കെത്തന്നെയാണ് ഇന്ത്യയിലെ ഇന്നുള്ള ചരിത്രപഠനവും. വെറും കുറച്ച് പതിറ്റാണ്ടുകൾ മാത്രം വയസ്സുള്ള ഒരു രാജ്യം ദക്ഷിണേഷ്യയുടെ ഭൂതകാലത്തെ അത്രയും സ്വന്തം കൈകളിൽ അടക്കിവച്ചിരിക്കുകയാണ്. പണ്ടത്തെ ദക്ഷിണേഷ്യയിലുള്ള വ്യത്യസ്ത പ്രദേശങ്ങളിൽ ജീവിച്ചിരുന്നവർ തങ്ങൾ ഇന്ത്യാക്കാരാണ് എന്ന് അത്മാഭിമാനത്തോടുകൂടി പറഞ്ഞിരിക്കാൻ യാതോരു സാധ്യതയും ഇല്ലതന്നെ.

ഭാവിയിൽ ഈ പ്രദേശത്ത് ഇന്നില്ലാത്ത കുറേ രാജ്യങ്ങൾ വളർന്നുവന്നാൽ, ഇന്ന് ഇന്ത്യ പറഞ്ഞൊപ്പിച്ച എല്ലാ ചരിത്ര പഠനവും അർത്ഥശൂന്യമാകും.

ഈ രീതിയിലാണോ ചരിത്രം എഴുതുകയും പഠിക്കുകയും ചെയ്യേണ്ടത് എന്ന ഒരു ചോദ്യം മനസ്സിൽ കയറിനിൽക്കുന്നുണ്ട്.

ഈ വിഷയത്തിലേക്ക് കൂടുതൽ കടക്കുന്നില്ല.

എന്നാൽ ഈ വിധം ഇവിടെ എഴുതാനുള്ള ഒരു പ്രേരണ ലഭിച്ചത് Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങളെക്കുറിച്ച് ചിലയിടത്ത് എഴുതിയത് കണ്ടതിലെ ചേതോവികാരം കണ്ടറിഞ്ഞതു കൊണ്ടാണ്. ഇദ്ദേഹത്തെ ഒരു ഇന്ത്യൻ സ്വാതന്ത്ര്യ സമര നേതാവോ സ്വാതന്ത്ര്യ സമര താത്വികാചാര്യനോ മറ്റോ ആയി പുനഃപ്രതിഷ്ഠിക്കാനുള്ള ഒരു പാഴ്വേല കാണുന്നില്ലേ എന്നൊരു സംശയം.

ഇദ്ദേഹം ജീവിച്ചിരുന്ന കാലഘട്ടത്തിൽ ഇന്ത്യയില്ലതന്നെ. പോരാത്തതിന്, ബൃട്ടിഷ്-ഇന്ത്യ തന്നെ പൂർണ്ണരൂപത്തിൽ എത്തിയിട്ടില്ല എന്നാണ് തോന്നുന്നത്. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കമ്പനിയും പിന്നീട് ബൃട്ടിഷ് ഭരണവും ഇവിടെ സാവധനത്തിൽ ഒരു രാഷ്ട്രം കെട്ടിപ്പടുത്തു കൊണ്ടിരിക്കുകയായിരുന്നു അന്ന്.

Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കൊളോണിയൽ വാഴ്ചക്ക് എതിരായിട്ടാണ് പൊരുതിയത് എന്ന് വിജ്ഞാനികൾ ആവർത്തിച്ചാവർത്തിച്ച് പറയുന്നുണ്ട് എങ്കിലും വാസ്തവത്തിൽ ഇദ്ദേഹത്തിന്റെ ദൃഷ്ടികേന്ദ്രം കാലാകാലങ്ങളായി ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിൽ ജീവിച്ചിരുന്ന പാരമ്പര്യ അധികാരി വർഗ്ഗത്തിൽ തന്നെയായിരുന്നു.

മാപ്പിള കർഷകരുടേയും മറ്റു കുടിയന്മാരുടേയും പരിവേദനങ്ങൾ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരെ നേരിട്ട് അറിയിക്കാൻ യാതോരു പഴുതോ പാതയോ ഈ കീഴ്ജന കൂട്ടർക്ക് ഇല്ലായിരുന്നു. അവരെക്കുറിച്ചുള്ളതും അവരുടേതായതുമായ എന്തുവിവരവും ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥർക്ക് ലഭിക്കുന്നത് അവരുടെ ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥ പ്രസ്ഥാനത്തിലെ പ്രഗൽഭരായ ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരായ പാരമ്പര്യ അധികാരികളിലൂടേയും മറ്റ് ഭൂജന്മി കുടുംബക്കാരിലൂടേയും തന്നെയായിരുന്നു.

ഇവരെ മാറ്റി കീഴ്ജനത്തിനെ ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരാക്കിയാൽ സാമൂഹിക വ്യവസ്ഥതി ആകെ താറുമാറാകും എന്നല്ലാതെ യാതോരു പ്രയോജനവും വരില്ലതന്നെ. കാരണം, ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷാ പ്രദേശങ്ങളിൽ സമൂഹത്തിലെ വ്യക്തികളെ നിയന്ത്രിക്കാൻ പറ്റുന്ന ആളുകളിലൂടെ വേണം ഭരണം നടത്താൻ. അതിന് സാമൂഹികമായി എന്തെങ്കിലും ഒരു വരേണ്യ നാമം ആ വ്യക്തിയിൽ നിക്ഷിപ്തമായിരിക്കേണം.

ഇന്നും ഈ ഒരു കാര്യം വാസ്തവം തന്നെയാണ്. സർക്കാരിന് ഏതെങ്കിലും പ്രദേശങ്ങളിൽ എന്തെങ്കിലും ഒരു സംഗതിക്കായി ജനങ്ങളെ അണിനിരത്തിയും കൂട്ടംചേർത്തും അവരെ നിയന്ത്രിക്കാൻ മലബാറിൽ പലപ്പോഴും പേരിന് പിന്നിൽ ഒരു മാഷ് എന്ന വാക്ക് ഉള്ളവരെ സർക്കാർ ഉപയോഗിക്കുന്നത് കണ്ടിട്ടുണ്ട്. അല്ലാതെ വറും പേരുകാരായ കണാരനേയും കിട്ടനേയും മറ്റും ഈ വിധമായുള്ള അനൗപചാരിക നേതൃത്വ സ്ഥാനങ്ങളിൽ സ്ഥാപിച്ചാൽ ആരും തിരിഞ്ഞുനേക്കില്ലതന്നെ.

ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥർക്ക് സാമൂഹത്തിന്റെ ഉള്ളറകളിലേക്ക് നേരിട്ട് കടുന്നവന്ന് ഇഴകിച്ചേരാൻ പ്രയാസം തന്നെയാണ്. കാരണം, പ്രാദേശിക വ്യക്തികൾ തമ്മിൽ കോർത്തിണക്കപ്പെട്ടിട്ടുള്ളത് ഇഞ്ഞി, ഇങ്ങൾ, ഓൻ, ഓള്, ഓര്, ഓല്, ഓറ്, ഐറ്റിങ്ങൾ, എടാ, എടീ, അനെ, അളെ, ചേട്ടൻ, ചേച്ചി, അനിയൻ, അനിയത്തി, ചെക്കൻ, പെണ്ണ് എന്നെല്ലാം വാക്കുകളിൽ ആണ്. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥർ ഈ വ്യക്തി ബന്ധ സങ്കീർണ്ണതയിൽ കയറിക്കൂടിയാൽ അവരും ഇതേ വാക്കുകൾ പറയുകയും അവയുടെ പിടിവലികളിൽ അവരും പെടുകയും ചെയ്യും. അതോടെ അവരുടെ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് പ്രതിച്ഛായ തന്നെ മാഞ്ഞുപോകും.

ഇന്നും ഇത് ഒരു സാമൂഹിക വാസ്തവം തന്നെയാണ്. മുകളിൽ ഉള്ള വ്യക്തികൾ താഴേതട്ടിലുള്ള വ്യക്തി ബന്ധ കണ്ണികളിൽ നിന്നും വിട്ടും ഉയർന്നും നിൽക്കും. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷിൽ ആവുന്നതു മാതിരി താഴെതട്ടിലുള്ളവരോടു യാതോരു അതിരുകളും വെക്കാതെ പെരുമാറിയാൽ ആള് നാറിപ്പോകും എന്നല്ലാതെ യാതോരു പ്രയോജനവും കിട്ടില്ല.

ദക്ഷിണേഷ്യൻ സാമൂഹങ്ങൾക്ക് ഒരു തരം അപ്രവേശ്യ (impermeable) സ്വഭാവം ഉണ്ട് എന്ന് പല ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരും മനസ്സിലാക്കിയിട്ടുണ്ട് എന്നാണ് കാണുന്നത്.

മാപ്പിള കുടിയാന്മാർക്ക് മാത്രമല്ല മറിച്ച് മുഹമ്മദീയരല്ലാത്ത കുടിയാന്മാർക്കും മറ്റ് കൃഷിക്കാർക്കും മറ്റും പലതും ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണത്തിനെ അറിയിക്കണം എന്നുണ്ടായിരുന്നു.

എന്നാൽ അവർക്ക് മുകളിൽ ഒരു വൻ കമ്പിളിപ്പുതപ്പുപോലെ അവരെ അമർത്തിപ്പിടിച്ചു നിൽക്കുന്ന അധികാരി കുടുംബക്കാരേയും ഭൂജന്മികുടുംബക്കാരേയും മറികടന്ന് അവരുടെ മുകളിലേക്ക് ചാടിക്കടന്ന് ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരെ കാര്യങ്ങൾ അറിയിക്കാൻ അവർ ശ്രമിച്ചിരുന്നു എന്ന സൂചന നൽകുന്ന് രണ്ട് വ്യത്യസ്ത സംഭവങ്ങൾ തന്നെ ഈ എഴുത്തുകാരന്റെ ശ്രദ്ധയിൽ വന്നിട്ടുണ്ട്.

ആ കാര്യങ്ങൾ പിന്നീട് പറയാം.

ഇനി Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങളുടെ കാര്യത്തിലേക്ക് നിങ്ങാം.

ഇദ്ദേഹം ശുദ്ധമായ അറബി രക്തപാതയിൽ ഉള്ള വ്യക്തിയാണ്. അതിനാൽ തന്നെ പ്രാദേശിക ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷാ വാക്കുകൾക്ക് ഇദ്ദേഹത്തെ ഒരു പരിധിക്കപ്പുറം മുറിവേൽപ്പിക്കാൻ പറ്റില്ല. എന്നിരുന്നാലും പൊതുവായി പറഞ്ഞാൽ ആ വക വാക്കുകൾ മുഹമ്മദീയരിലെ തങ്ങൾ വ്യക്തികൾക്ക് നേരെ ഉപയോഗിക്കാൻ പാടില്ലാ എന്ന ചട്ടം കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാർക്ക് മനസ്സിലാക്കിക്കൊടുത്തിരുന്നു.

നായർമാരെ 'ഇങ്ങൾ' എന്ന പദത്തിൽ സംബോധന ചെയ്യേണ്ട എന്ന് Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാർക്ക് നിർദ്ദേശം നൽകിയിരുന്നു എന്ന ഒരു കാര്യം ഈ എഴുത്തുകാരന്റെ ശ്രദ്ധയിൽ വന്ന കാര്യം നേരത്തെ സൂചിപ്പിച്ചിരുന്നു. ഈ കാര്യം ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷിൽ എഴുതുമ്പോൾ അതിന്റെ സ്ഫോടന ശക്തിയെന്താണ് എന്ന് മനസ്സിലാക്കാൻ ആവില്ല.

പിന്നെ ഇദ്ദേഹം പള്ളിപ്രസംഗത്തിലോ മറ്റോ, അന്യായമായി കുടിഒഴിപ്പിക്കുന്ന ഭൂജന്മികളെ കൊല്ലുന്നത് ഒരു സുകൃതമാണ് എന്നും പറഞ്ഞുപോലും. ഇങ്ങിനെ ഒരു കാര്യം Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ പറഞ്ഞിരുന്നു എന്ന് ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരെ അറിയിച്ചത് മലബാർ ജില്ലയിലെ ഡപ്യൂട്ടി കലക്ടർ ആയിരുന്ന സി. കണാരൻ ആണ് പോലും.

ഈ സി. കണാരൻ, ചൂരയിൽ കണാരൻ എന്നോ മറ്റോ പേരിൽ അറിയപ്പെട്ടിരുന്ന തീയർ സമുദായക്കാരനായ വ്യക്തിയാണ് എന്നു തോന്നുന്നു. ഈ ആളുടെ കാര്യം പറഞ്ഞാൽ, ഈ ആൾ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണ പ്രസ്ഥാനത്തിൽ കയറിയ അവസരത്തിൽ ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരിലെ ഉന്നത ജാതിക്കാർ ഈ ആൾക്ക് ഓഫിനിൽ നിലത്തിരിക്കാനുള്ള സൗകര്യമാണ് നൽകിയത്.

ഒരിക്കൽ മലബാർ ജില്ലാ കലക്ടറായിരുുന്ന Henry Conolly, ഔദ്യോഗിക ആവശ്യത്തിനായി Tellicherry Sub Divisional Officeസിൽ വന്നപ്പോൾ കണ്ടത് ഈ ഓഫിസർ പദവിക്കാരൻ നിലത്തിരുന്ന് തൊഴിൽ ചെയ്യുന്നതായിട്ടാണ്. ഉടനെ ഈ ആൾക്ക് ഇരിക്കാനുള്ള കസേരയും തൊഴിൽ ചെയ്യാനുള്ള മേശയും നൽകാൻ Conolly ഉത്തരവിട്ടുപോലും.

പ്രാദേശിക സമൂഹത്തിൽ പലവിധ വ്യക്തിവിദ്വേഷങ്ങൾ നിലനിന്നിരുന്നു. അതിനെല്ലാം മുകളിൽ നിൽക്കാനെ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് പക്ഷത്തിന് ആയുള്ളു.

സി. കണാരന് ഈ വിധം അവഹേളനപരമായുള്ള ഒരു അനുഭവം ഉന്നത ജനവംശങ്ങളിൽ നിന്നും ലഭിച്ചിരുന്നു എങ്കിലും, സാമൂഹികമായി ഉന്നതരായ ബ്രഹ്മണ പക്ഷക്കാരോടും ആ വിധ ഭൂജന്മികളേടും അധികാരികളോടും ഇദ്ദേഹത്തിന് വ്യക്തി ബന്ധം വളർന്നുവന്നിട്ടുണ്ടാവും എന്നത് സാധ്യമായ കാര്യം തന്നെയാണ്.

കുടിയൊഴിപ്പിക്കുന്ന ഭൂജന്മികളെ കൊല്ലണം എന്ന് യഥാർത്ഥത്തിൽ Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ പറഞ്ഞിരുന്നുവോ എന്നതും ചെറിയ തോതിലുള്ള ഒരു സംശയ ദൃഷ്ടിയോടുകൂടി നോക്കേണ്ടിയും വരാം. ഈ വിധമായുള്ള ഒരു കഥ ചിലപ്പോൾ കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാർ കെട്ടിച്ചമച്ചതായിരിക്കാം. അതുമല്ലായെങ്കിൽ ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷക്കാർ ഉണ്ടാക്കിയ കഥയാവാം.

കാരണം, കൊല്ലാൻ പദ്ധതിയിടുന്നതിനേക്കാൾ ആപൽക്കരമായിട്ടുള്ള ഒരു കാര്യമാണ് Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാർക്ക് പറഞ്ഞുകൊടുത്തത്. അതായത്, നായർമാരെ ഇങ്ങൾ എന്ന് സംബോധന ചെയ്യേണ്ട എന്ന്. എന്നുവച്ചാൽ, നായർമാരും സ്ത്രീകൾ അടക്കമുള്ള അവരുടെ കുടുംബക്കാരും ഇഞ്ഞി / ഇജ്ജ് നിലവാരത്തിലേക്ക് ഉരുണ്ട് വീഴാനുള്ള സാമൂഹിക കുഴിയാണ് Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ സൃഷ്ടിച്ചുകൊടുത്തിരിക്കുന്നത്.

കൊല്ലാനുള്ള പദ്ധതിയെ ആയുധവേലകൊണ്ട് തടയാം. വാക്ക് കോഡുകളിലൂടെയുള്ള ഇടിച്ചുതാഴ്ത്തലിനെ കാര്യക്ഷമമായി തടയാൻ, ആയുധം ഉപയോഗിച്ചുള്ള പ്രത്യാക്രമണം അല്ലാതെ മറ്റ് യാതോരു പ്രതിരോധ ഉപായവും ഇല്ലതന്നെ.

Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ വേറേയും ചില അതിഗംഭീരമായ ആക്രമണ പദ്ധതികൾ നടപ്പിലാക്കാൻ മാപ്പിളമാർക്ക് നിർദ്ദേശം നൽകിയിരുന്നു. അവയും തികച്ചും അഹിംസാപരമായുള്ള ആക്രമണങ്ങൾ തന്നെയായിരുന്നു. എന്നാൽ ഇന്നുള്ള ഇന്ത്യയുടെ പിതവ് എന്ന് മാധ്യമങ്ങളിൽ വെറുതേ പറയപ്പെടുന്ന വ്യക്തിപോലും അക്രമാസക്തനായേക്കാവുന്ന തരത്തിലുള്ള പദ്ധതികൾ ആണ് Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ ഉദ്ഘോഷിച്ച അംഹിസാപരമായുള്ള പദ്ധതികൾ.

നായർമാർക്ക് ഇദ്ദേഹത്തെ ഓടിച്ചുവിട്ടേ പറ്റൂ. അവരേയും കുറ്റം പറയാൻ ആവില്ല. കാരണം അവർക്കും തല ഉയർത്തിത്തന്നെ വേണം നാട്ടിൽ ജീവിക്കാൻ.

എന്നാൽ Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങളെ ഓടിക്കാൻ പ്രാപ്തിയുള്ളത് ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണത്തിനാണ്.

ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷം ഇരു പക്ഷത്തും തീകൊളുത്തി നടുവിൽ പിടിച്ചുനിന്നു വേണം കാര്യങ്ങൾ നടപ്പിലാക്കാൻ. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് പക്ഷം അധിനിവേഷക്കാർ ആണ് എങ്കിൽ Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങളും അധിനിവേഷക്കരൻ തന്നെ.

മാപ്പിളമാരിലും മക്കത്തായ തീയരിലും മരുമക്കത്തായ തീയരിലും അധിനിവേഷ രക്തബന്ധ പാതകൾ ഉണ്ട്. പോരാത്തതിന് മറ്റ് പല ജനവംശങ്ങളിലും ഇത് ഉണ്ട്.

ഉദാഹരണത്തിന്, പ്രപഞ്ചത്തിന്റെ മധ്യത്തിലാണ് നാം ഇരിക്കുന്നത് എന്ന ഭാവത്തിൽ പ്രപഞ്ചത്തിലെ മറ്റെല്ലാ വസ്തുക്കളേയും അവയുടെ നീക്കങ്ങളേയും അവയുടെ വേഗതേയും മറ്റും നമുക്ക് ആപേക്ഷികമായി അളക്കാനും വ്യാഖ്യാനിക്കാനും ആവും.

എന്നാൽ നമുക്ക് ലഭിക്കുന്ന എല്ലാവിവരങ്ങളും ഭൂമിയെന്ന Frame of referenceസിനുള്ളിൽ (ചട്ടക്കൂടിനുള്ളിൽ നിന്നുമുള്ള വീക്ഷണകോണിൽനിന്നും) മാത്രം സത്യമാകുന്ന കാര്യങ്ങൾ ആയേക്കാം. ഭൂമിയെ ഒന്ന് പിടിവിട്ടുകൊണ്ട് നീങ്ങിയാൽ, നമുക്ക് ലഭിച്ച എല്ലാ അളവുകളും ദിശകളും വേഗതകളും മറ്റും അർത്ഥശൂന്യമായിപ്പോകും.

അതേ പോലൊക്കെത്തന്നെയാണ് ഇന്ത്യയിലെ ഇന്നുള്ള ചരിത്രപഠനവും. വെറും കുറച്ച് പതിറ്റാണ്ടുകൾ മാത്രം വയസ്സുള്ള ഒരു രാജ്യം ദക്ഷിണേഷ്യയുടെ ഭൂതകാലത്തെ അത്രയും സ്വന്തം കൈകളിൽ അടക്കിവച്ചിരിക്കുകയാണ്. പണ്ടത്തെ ദക്ഷിണേഷ്യയിലുള്ള വ്യത്യസ്ത പ്രദേശങ്ങളിൽ ജീവിച്ചിരുന്നവർ തങ്ങൾ ഇന്ത്യാക്കാരാണ് എന്ന് അത്മാഭിമാനത്തോടുകൂടി പറഞ്ഞിരിക്കാൻ യാതോരു സാധ്യതയും ഇല്ലതന്നെ.

ഭാവിയിൽ ഈ പ്രദേശത്ത് ഇന്നില്ലാത്ത കുറേ രാജ്യങ്ങൾ വളർന്നുവന്നാൽ, ഇന്ന് ഇന്ത്യ പറഞ്ഞൊപ്പിച്ച എല്ലാ ചരിത്ര പഠനവും അർത്ഥശൂന്യമാകും.

ഈ രീതിയിലാണോ ചരിത്രം എഴുതുകയും പഠിക്കുകയും ചെയ്യേണ്ടത് എന്ന ഒരു ചോദ്യം മനസ്സിൽ കയറിനിൽക്കുന്നുണ്ട്.

ഈ വിഷയത്തിലേക്ക് കൂടുതൽ കടക്കുന്നില്ല.

എന്നാൽ ഈ വിധം ഇവിടെ എഴുതാനുള്ള ഒരു പ്രേരണ ലഭിച്ചത് Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങളെക്കുറിച്ച് ചിലയിടത്ത് എഴുതിയത് കണ്ടതിലെ ചേതോവികാരം കണ്ടറിഞ്ഞതു കൊണ്ടാണ്. ഇദ്ദേഹത്തെ ഒരു ഇന്ത്യൻ സ്വാതന്ത്ര്യ സമര നേതാവോ സ്വാതന്ത്ര്യ സമര താത്വികാചാര്യനോ മറ്റോ ആയി പുനഃപ്രതിഷ്ഠിക്കാനുള്ള ഒരു പാഴ്വേല കാണുന്നില്ലേ എന്നൊരു സംശയം.

ഇദ്ദേഹം ജീവിച്ചിരുന്ന കാലഘട്ടത്തിൽ ഇന്ത്യയില്ലതന്നെ. പോരാത്തതിന്, ബൃട്ടിഷ്-ഇന്ത്യ തന്നെ പൂർണ്ണരൂപത്തിൽ എത്തിയിട്ടില്ല എന്നാണ് തോന്നുന്നത്. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കമ്പനിയും പിന്നീട് ബൃട്ടിഷ് ഭരണവും ഇവിടെ സാവധനത്തിൽ ഒരു രാഷ്ട്രം കെട്ടിപ്പടുത്തു കൊണ്ടിരിക്കുകയായിരുന്നു അന്ന്.

Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കൊളോണിയൽ വാഴ്ചക്ക് എതിരായിട്ടാണ് പൊരുതിയത് എന്ന് വിജ്ഞാനികൾ ആവർത്തിച്ചാവർത്തിച്ച് പറയുന്നുണ്ട് എങ്കിലും വാസ്തവത്തിൽ ഇദ്ദേഹത്തിന്റെ ദൃഷ്ടികേന്ദ്രം കാലാകാലങ്ങളായി ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിൽ ജീവിച്ചിരുന്ന പാരമ്പര്യ അധികാരി വർഗ്ഗത്തിൽ തന്നെയായിരുന്നു.

മാപ്പിള കർഷകരുടേയും മറ്റു കുടിയന്മാരുടേയും പരിവേദനങ്ങൾ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരെ നേരിട്ട് അറിയിക്കാൻ യാതോരു പഴുതോ പാതയോ ഈ കീഴ്ജന കൂട്ടർക്ക് ഇല്ലായിരുന്നു. അവരെക്കുറിച്ചുള്ളതും അവരുടേതായതുമായ എന്തുവിവരവും ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥർക്ക് ലഭിക്കുന്നത് അവരുടെ ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥ പ്രസ്ഥാനത്തിലെ പ്രഗൽഭരായ ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരായ പാരമ്പര്യ അധികാരികളിലൂടേയും മറ്റ് ഭൂജന്മി കുടുംബക്കാരിലൂടേയും തന്നെയായിരുന്നു.

ഇവരെ മാറ്റി കീഴ്ജനത്തിനെ ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരാക്കിയാൽ സാമൂഹിക വ്യവസ്ഥതി ആകെ താറുമാറാകും എന്നല്ലാതെ യാതോരു പ്രയോജനവും വരില്ലതന്നെ. കാരണം, ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷാ പ്രദേശങ്ങളിൽ സമൂഹത്തിലെ വ്യക്തികളെ നിയന്ത്രിക്കാൻ പറ്റുന്ന ആളുകളിലൂടെ വേണം ഭരണം നടത്താൻ. അതിന് സാമൂഹികമായി എന്തെങ്കിലും ഒരു വരേണ്യ നാമം ആ വ്യക്തിയിൽ നിക്ഷിപ്തമായിരിക്കേണം.

ഇന്നും ഈ ഒരു കാര്യം വാസ്തവം തന്നെയാണ്. സർക്കാരിന് ഏതെങ്കിലും പ്രദേശങ്ങളിൽ എന്തെങ്കിലും ഒരു സംഗതിക്കായി ജനങ്ങളെ അണിനിരത്തിയും കൂട്ടംചേർത്തും അവരെ നിയന്ത്രിക്കാൻ മലബാറിൽ പലപ്പോഴും പേരിന് പിന്നിൽ ഒരു മാഷ് എന്ന വാക്ക് ഉള്ളവരെ സർക്കാർ ഉപയോഗിക്കുന്നത് കണ്ടിട്ടുണ്ട്. അല്ലാതെ വറും പേരുകാരായ കണാരനേയും കിട്ടനേയും മറ്റും ഈ വിധമായുള്ള അനൗപചാരിക നേതൃത്വ സ്ഥാനങ്ങളിൽ സ്ഥാപിച്ചാൽ ആരും തിരിഞ്ഞുനേക്കില്ലതന്നെ.

ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥർക്ക് സാമൂഹത്തിന്റെ ഉള്ളറകളിലേക്ക് നേരിട്ട് കടുന്നവന്ന് ഇഴകിച്ചേരാൻ പ്രയാസം തന്നെയാണ്. കാരണം, പ്രാദേശിക വ്യക്തികൾ തമ്മിൽ കോർത്തിണക്കപ്പെട്ടിട്ടുള്ളത് ഇഞ്ഞി, ഇങ്ങൾ, ഓൻ, ഓള്, ഓര്, ഓല്, ഓറ്, ഐറ്റിങ്ങൾ, എടാ, എടീ, അനെ, അളെ, ചേട്ടൻ, ചേച്ചി, അനിയൻ, അനിയത്തി, ചെക്കൻ, പെണ്ണ് എന്നെല്ലാം വാക്കുകളിൽ ആണ്. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥർ ഈ വ്യക്തി ബന്ധ സങ്കീർണ്ണതയിൽ കയറിക്കൂടിയാൽ അവരും ഇതേ വാക്കുകൾ പറയുകയും അവയുടെ പിടിവലികളിൽ അവരും പെടുകയും ചെയ്യും. അതോടെ അവരുടെ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് പ്രതിച്ഛായ തന്നെ മാഞ്ഞുപോകും.

ഇന്നും ഇത് ഒരു സാമൂഹിക വാസ്തവം തന്നെയാണ്. മുകളിൽ ഉള്ള വ്യക്തികൾ താഴേതട്ടിലുള്ള വ്യക്തി ബന്ധ കണ്ണികളിൽ നിന്നും വിട്ടും ഉയർന്നും നിൽക്കും. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷിൽ ആവുന്നതു മാതിരി താഴെതട്ടിലുള്ളവരോടു യാതോരു അതിരുകളും വെക്കാതെ പെരുമാറിയാൽ ആള് നാറിപ്പോകും എന്നല്ലാതെ യാതോരു പ്രയോജനവും കിട്ടില്ല.

ദക്ഷിണേഷ്യൻ സാമൂഹങ്ങൾക്ക് ഒരു തരം അപ്രവേശ്യ (impermeable) സ്വഭാവം ഉണ്ട് എന്ന് പല ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരും മനസ്സിലാക്കിയിട്ടുണ്ട് എന്നാണ് കാണുന്നത്.

മാപ്പിള കുടിയാന്മാർക്ക് മാത്രമല്ല മറിച്ച് മുഹമ്മദീയരല്ലാത്ത കുടിയാന്മാർക്കും മറ്റ് കൃഷിക്കാർക്കും മറ്റും പലതും ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണത്തിനെ അറിയിക്കണം എന്നുണ്ടായിരുന്നു.

എന്നാൽ അവർക്ക് മുകളിൽ ഒരു വൻ കമ്പിളിപ്പുതപ്പുപോലെ അവരെ അമർത്തിപ്പിടിച്ചു നിൽക്കുന്ന അധികാരി കുടുംബക്കാരേയും ഭൂജന്മികുടുംബക്കാരേയും മറികടന്ന് അവരുടെ മുകളിലേക്ക് ചാടിക്കടന്ന് ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരെ കാര്യങ്ങൾ അറിയിക്കാൻ അവർ ശ്രമിച്ചിരുന്നു എന്ന സൂചന നൽകുന്ന് രണ്ട് വ്യത്യസ്ത സംഭവങ്ങൾ തന്നെ ഈ എഴുത്തുകാരന്റെ ശ്രദ്ധയിൽ വന്നിട്ടുണ്ട്.

ആ കാര്യങ്ങൾ പിന്നീട് പറയാം.

ഇനി Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങളുടെ കാര്യത്തിലേക്ക് നിങ്ങാം.

ഇദ്ദേഹം ശുദ്ധമായ അറബി രക്തപാതയിൽ ഉള്ള വ്യക്തിയാണ്. അതിനാൽ തന്നെ പ്രാദേശിക ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷാ വാക്കുകൾക്ക് ഇദ്ദേഹത്തെ ഒരു പരിധിക്കപ്പുറം മുറിവേൽപ്പിക്കാൻ പറ്റില്ല. എന്നിരുന്നാലും പൊതുവായി പറഞ്ഞാൽ ആ വക വാക്കുകൾ മുഹമ്മദീയരിലെ തങ്ങൾ വ്യക്തികൾക്ക് നേരെ ഉപയോഗിക്കാൻ പാടില്ലാ എന്ന ചട്ടം കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാർക്ക് മനസ്സിലാക്കിക്കൊടുത്തിരുന്നു.

നായർമാരെ 'ഇങ്ങൾ' എന്ന പദത്തിൽ സംബോധന ചെയ്യേണ്ട എന്ന് Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാർക്ക് നിർദ്ദേശം നൽകിയിരുന്നു എന്ന ഒരു കാര്യം ഈ എഴുത്തുകാരന്റെ ശ്രദ്ധയിൽ വന്ന കാര്യം നേരത്തെ സൂചിപ്പിച്ചിരുന്നു. ഈ കാര്യം ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷിൽ എഴുതുമ്പോൾ അതിന്റെ സ്ഫോടന ശക്തിയെന്താണ് എന്ന് മനസ്സിലാക്കാൻ ആവില്ല.

പിന്നെ ഇദ്ദേഹം പള്ളിപ്രസംഗത്തിലോ മറ്റോ, അന്യായമായി കുടിഒഴിപ്പിക്കുന്ന ഭൂജന്മികളെ കൊല്ലുന്നത് ഒരു സുകൃതമാണ് എന്നും പറഞ്ഞുപോലും. ഇങ്ങിനെ ഒരു കാര്യം Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ പറഞ്ഞിരുന്നു എന്ന് ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരെ അറിയിച്ചത് മലബാർ ജില്ലയിലെ ഡപ്യൂട്ടി കലക്ടർ ആയിരുന്ന സി. കണാരൻ ആണ് പോലും.

ഈ സി. കണാരൻ, ചൂരയിൽ കണാരൻ എന്നോ മറ്റോ പേരിൽ അറിയപ്പെട്ടിരുന്ന തീയർ സമുദായക്കാരനായ വ്യക്തിയാണ് എന്നു തോന്നുന്നു. ഈ ആളുടെ കാര്യം പറഞ്ഞാൽ, ഈ ആൾ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണ പ്രസ്ഥാനത്തിൽ കയറിയ അവസരത്തിൽ ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരിലെ ഉന്നത ജാതിക്കാർ ഈ ആൾക്ക് ഓഫിനിൽ നിലത്തിരിക്കാനുള്ള സൗകര്യമാണ് നൽകിയത്.

ഒരിക്കൽ മലബാർ ജില്ലാ കലക്ടറായിരുുന്ന Henry Conolly, ഔദ്യോഗിക ആവശ്യത്തിനായി Tellicherry Sub Divisional Officeസിൽ വന്നപ്പോൾ കണ്ടത് ഈ ഓഫിസർ പദവിക്കാരൻ നിലത്തിരുന്ന് തൊഴിൽ ചെയ്യുന്നതായിട്ടാണ്. ഉടനെ ഈ ആൾക്ക് ഇരിക്കാനുള്ള കസേരയും തൊഴിൽ ചെയ്യാനുള്ള മേശയും നൽകാൻ Conolly ഉത്തരവിട്ടുപോലും.

പ്രാദേശിക സമൂഹത്തിൽ പലവിധ വ്യക്തിവിദ്വേഷങ്ങൾ നിലനിന്നിരുന്നു. അതിനെല്ലാം മുകളിൽ നിൽക്കാനെ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് പക്ഷത്തിന് ആയുള്ളു.

സി. കണാരന് ഈ വിധം അവഹേളനപരമായുള്ള ഒരു അനുഭവം ഉന്നത ജനവംശങ്ങളിൽ നിന്നും ലഭിച്ചിരുന്നു എങ്കിലും, സാമൂഹികമായി ഉന്നതരായ ബ്രഹ്മണ പക്ഷക്കാരോടും ആ വിധ ഭൂജന്മികളേടും അധികാരികളോടും ഇദ്ദേഹത്തിന് വ്യക്തി ബന്ധം വളർന്നുവന്നിട്ടുണ്ടാവും എന്നത് സാധ്യമായ കാര്യം തന്നെയാണ്.

കുടിയൊഴിപ്പിക്കുന്ന ഭൂജന്മികളെ കൊല്ലണം എന്ന് യഥാർത്ഥത്തിൽ Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ പറഞ്ഞിരുന്നുവോ എന്നതും ചെറിയ തോതിലുള്ള ഒരു സംശയ ദൃഷ്ടിയോടുകൂടി നോക്കേണ്ടിയും വരാം. ഈ വിധമായുള്ള ഒരു കഥ ചിലപ്പോൾ കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാർ കെട്ടിച്ചമച്ചതായിരിക്കാം. അതുമല്ലായെങ്കിൽ ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷക്കാർ ഉണ്ടാക്കിയ കഥയാവാം.

കാരണം, കൊല്ലാൻ പദ്ധതിയിടുന്നതിനേക്കാൾ ആപൽക്കരമായിട്ടുള്ള ഒരു കാര്യമാണ് Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാർക്ക് പറഞ്ഞുകൊടുത്തത്. അതായത്, നായർമാരെ ഇങ്ങൾ എന്ന് സംബോധന ചെയ്യേണ്ട എന്ന്. എന്നുവച്ചാൽ, നായർമാരും സ്ത്രീകൾ അടക്കമുള്ള അവരുടെ കുടുംബക്കാരും ഇഞ്ഞി / ഇജ്ജ് നിലവാരത്തിലേക്ക് ഉരുണ്ട് വീഴാനുള്ള സാമൂഹിക കുഴിയാണ് Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ സൃഷ്ടിച്ചുകൊടുത്തിരിക്കുന്നത്.

കൊല്ലാനുള്ള പദ്ധതിയെ ആയുധവേലകൊണ്ട് തടയാം. വാക്ക് കോഡുകളിലൂടെയുള്ള ഇടിച്ചുതാഴ്ത്തലിനെ കാര്യക്ഷമമായി തടയാൻ, ആയുധം ഉപയോഗിച്ചുള്ള പ്രത്യാക്രമണം അല്ലാതെ മറ്റ് യാതോരു പ്രതിരോധ ഉപായവും ഇല്ലതന്നെ.

Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ വേറേയും ചില അതിഗംഭീരമായ ആക്രമണ പദ്ധതികൾ നടപ്പിലാക്കാൻ മാപ്പിളമാർക്ക് നിർദ്ദേശം നൽകിയിരുന്നു. അവയും തികച്ചും അഹിംസാപരമായുള്ള ആക്രമണങ്ങൾ തന്നെയായിരുന്നു. എന്നാൽ ഇന്നുള്ള ഇന്ത്യയുടെ പിതവ് എന്ന് മാധ്യമങ്ങളിൽ വെറുതേ പറയപ്പെടുന്ന വ്യക്തിപോലും അക്രമാസക്തനായേക്കാവുന്ന തരത്തിലുള്ള പദ്ധതികൾ ആണ് Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങൾ ഉദ്ഘോഷിച്ച അംഹിസാപരമായുള്ള പദ്ധതികൾ.

നായർമാർക്ക് ഇദ്ദേഹത്തെ ഓടിച്ചുവിട്ടേ പറ്റൂ. അവരേയും കുറ്റം പറയാൻ ആവില്ല. കാരണം അവർക്കും തല ഉയർത്തിത്തന്നെ വേണം നാട്ടിൽ ജീവിക്കാൻ.

എന്നാൽ Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങളെ ഓടിക്കാൻ പ്രാപ്തിയുള്ളത് ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണത്തിനാണ്.

ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷം ഇരു പക്ഷത്തും തീകൊളുത്തി നടുവിൽ പിടിച്ചുനിന്നു വേണം കാര്യങ്ങൾ നടപ്പിലാക്കാൻ. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് പക്ഷം അധിനിവേഷക്കാർ ആണ് എങ്കിൽ Sayyid Fazal തങ്ങളും അധിനിവേഷക്കരൻ തന്നെ.

മാപ്പിളമാരിലും മക്കത്തായ തീയരിലും മരുമക്കത്തായ തീയരിലും അധിനിവേഷ രക്തബന്ധ പാതകൾ ഉണ്ട്. പോരാത്തതിന് മറ്റ് പല ജനവംശങ്ങളിലും ഇത് ഉണ്ട്.

Last edited by VED on Sun Jun 15, 2025 11:25 am, edited 2 times in total.

2. ഹിന്ദി ഇംപീരിയലിസത്തിന് കൂറ് കാണിക്കുന്നത് സ്വാതന്ത്ര്യമാവുന്നത്

മാപ്പിള അഥവാ മുഹമ്മദീയ കീഴ്ജന അക്രമങ്ങളെക്കുറിച്ച് ചിന്തിക്കുമ്പോൾ, സാമൂഹികവും രാഷ്ട്രീയവും ആയുള്ള വിപ്ളവങ്ങളെക്കുറിച്ച് ഒന്ന് ആലോചിക്കേണ്ടതുണ്ട്.

ഇന്നത്തെ പാലസ്തീൻകാരുടെ സ്വാതന്ത്ര്യ സമരത്തെക്കുറിച്ച് ആലോചിക്കാം. അവരുടെ ഭാഷ അറബിയാണ് എന്നു തോന്നുന്നു.

പാലസ്തീനിൽ ഇന്ത്യാക്കാരും മറ്റ് ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷക്കാരും കാര്യമായി ഇല്ലാ എന്നാണ് തോന്നുന്നത്.

ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷക്കാരുടെ സാന്നിദ്ധ്യത്തെക്കുറിച്ച് പറഞ്ഞതിന്റെ കാര്യം ഇതാണ്:

ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷക്കാരുടെ സാന്നിദ്ധ്യം ഉണ്ട് എങ്കിൽ അത് അറബി ഭാഷയേയും സ്വാധീനിക്കും. പോരാത്തതിന് അത് ആഭാഷയെ ഒരു പരിധിവരെ വികലപ്പെടുത്തുകയും ചെയ്തേക്കാം. ഈ പറഞ്ഞത് വെറും ഒരു ഊഹോപോഹം മാത്രമാണ്. കാരണം, ഈ എഴുത്തുകാരന് അറബി അറിയില്ല.

എന്നിരുന്നാലും, ഭാഷകോഡുകളിൽ മാനസികമായി മലമുകളിൽ ഉള്ളവരേയും, കുഴിയിൽ പെട്ടുകിടക്കുന്നവരേയും അറബി ഭാഷ വ്യത്യസ്തരായി അഭിമുഖീകരിക്കുമ്പോൾ, ആ ഭാഷയിലെ നൈസർഗികമായ വാക്ക് കോഡുകൾക്ക് ഒരു പര്യാപ്തതക്കുറവ് അനുഭവപ്പെട്ടേക്കാം. പോരാത്തതിന്, ഈ കൂട്ടർ അറബി ജനത്തിനേയും നിർവ്വചിക്കുന്ന അനുഭവവും അറബി പക്ഷക്കാരിൽ ചെറിയ തോതിലുള്ള ഭാവപ്പകർച്ചകൾ സൃഷ്ടിച്ചേക്കാം. അതും ഭാഷാ വാക്ക്കോഡുകളിൽ മാറ്റം വരുത്തിയേക്കാം.

ഇനി പാലസ്ത്തീൻകാരുടെ കാര്യം. അവരുടെ ഭാഷ മലയാളം, തമിഴ്, ഹിന്ദി തുടങ്ങിയ ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷകളെപ്പോലെയാണ് എങ്കിൽ ആ ജനതയ്ക്ക് ഒറ്റക്കെട്ടായുള്ള ഒരു ചെറുത്ത് നിൽപ്പ് ആവില്ലതന്നെ. ആവുമെങ്കിൽതന്നെ അവയെല്ലാം വളരെ വേഗത്തിൽ പല ഗ്രൂപ്പുകളായി ചിന്നിച്ചിതറുമായിരുന്നു.

പോരാത്തതിന്, ഇസ്റേലി ആക്രമണങ്ങളിൽ വീടുകളും മറ്റും നഷ്ടപ്പെട്ടാൽ വ്യക്തികൾക്ക് തമ്മിൽ സംസാരിക്കാൻ തന്നെ പ്രയാസം നേരിടും. കാരണം, മുകളിൽ സൂചിപ്പിച്ച ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷാ ആശയവിനിമയത്തിൽ വീടിന്റെ മഹിമ ഒരു പ്രധാന ഘടകമാണ്. വീട് തരിപ്പണമായാൽ, വ്യക്തിയും വാക്ക് കോഡുകളിൽ തരിപ്പണമായിപ്പോകും.

അറബി ഭാഷാ വാക്ക്കോഡുകൾ തമ്മിൽ തെറ്റിക്കാതെ നിർത്തുന്ന അവിടുള്ള ജനത്തിന് ഇസ്ലാം കൂടുതലായുള്ള ഒരു ഐക്യബോധം വരുത്തുന്നുണ്ട് എന്നത് ശരിയാണ് എങ്കിലും, മറ്റ് ഇസ്ലാം രാഷ്ട്രങ്ങൾ മിക്കവയും പാലസ്ത്തീകാരുടെ പ്രശ്നത്തിൽ ഒരു തണുപ്പൻ പ്രതികരണമാണ് നൽകിയത് എന്നും ഓർക്കുക.

ബൃട്ടിഷ്-ഇന്ത്യയെ Clement Atlee നെഹ്റുപക്ഷത്തിന് നൽകുകയും ആ കൂട്ടർ ഒരു ഹിന്ദി ഇംപീരിയലിസം ഈ ഉപഭൂഖണ്ഡത്തിൽ നടപ്പിലാക്കാൻ ശ്രമിക്കുകയും ചെയ്തപ്പോൾ, ബൃട്ടിഷ്-ഇന്ത്യയിൽ എല്ലായിടത്തും സാമൂഹികമായി ഉന്നതരായുള്ള വ്യക്തികൾ പുതിയ ഭരണപ്രസ്ഥാനത്തിൽ പിടിച്ചുകയറാനും സ്വന്തം പ്രദേശത്തുള്ള മറ്റുവ്യക്തികളെ പിന്നിലാക്കാനും ആണ് വെപ്രാളപ്പെട്ടും ധൃതിപിടിച്ചും ശ്രമിച്ചത്.

കുറച്ചുകൂടി വ്യക്തമായി പറഞ്ഞാൽ, ബൃട്ടിഷ്-മലബാറിൽ കുറച്ച് വകതിരുവുള്ള ഏതൊരു വ്യക്തിക്കും മനസ്സിലാക്കുവന്നതേയുള്ള, ഈ പ്രദേശം ചരിത്രത്തിൽ ഒരിക്കൽ പോലും ഹിന്ദിക്കാരുടെ കീഴിൽ വരാത്ത പ്രദേശമാണ് എന്ന്. പോരാത്തതിന്, മലബാറി ഭാഷയിൽ സംസ്കൃതവാക്കുകൾ പോലും വളരെ നിസ്സാരമായേ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നുള്ളു.

അതേ സമയം സംസ്കൃത വാക്കുകൾ മിക്ക ദക്ഷിണേഷ്യൻ ഭാഷകളിലും അടുത്തകാലത്ത് കൂട്ടിച്ചേർത്തവ മാത്രമാണ് എന്നതും ഇവിടെ പ്രസ്താവ്യമാണ്. ഈ സംസ്കൃത ഭാഷാ വാക്കുകൾ ഈ ഉപഭൂഖണ്ഡത്തിലെ ഭാഷകളിൽ നിന്നും മാച്ചുകളഞ്ഞാൽ, ഇന്നുള്ള ഇന്ത്യയെന്ന സങ്കൽപ്പം തന്നെ നിർവ്വീര്യമാകും.

മലബാറുകാർക്ക് തമ്മിൽ സംഘടിക്കാനും സഹകരിക്കാനും ആവുന്ന ഭാഷയല്ല പ്രാദേശിക ഭാഷ. എന്നാൽ ഉപഭൂഖണ്ഡത്തിന്റെ വടക്കൻ പ്രദേശങ്ങളിലെ രാഷ്ടീയ നേതാക്കളുടെ പേരിന് കീഴിൽ അണിനിരന്നാൽ ഒരു കൃത്രിമമായിട്ടുള്ള ഐക്യബോധം കൈവരും. ഇതാണ് ബൃട്ടിഷ്-മലബാറിനെ ഹിന്ദി ഇംപീരിയലിസത്തിന് കീഴിൽ എത്തിച്ചത്.

ഈ വിഷയത്തെക്കുറിച്ച് ഇവിടെ കൂടുതലായുള്ള വിശകലനത്തിന് പോകുന്നില്ല. എന്നാൽ ഇതിൽ നിന്നും ചില കാര്യങ്ങൾ മലബാറിലെ മാപ്പിള ആക്രമണ പ്രശ്നത്തിലേക്ക് വലിച്ചെടുക്കുകയാണ്. അവ പൂർണ്ണമായും മലബാറിൽ ശരിയാവണമെന്നില്ല.

എന്നാൽ നോക്കൂ:

മൈസൂറുകാരുടെ ആക്രമണം പല കീഴ്ജന വ്യക്തികൾക്കും അവരുടെ കന്നുകാലി നിലവാരത്തിലുള്ള അടിമ അവസ്ഥയിൽ നിന്നും രക്ഷപ്പെടാൻ സൗകര്യം നൽകി. അവരിൽ പലരും ഇസ്ലാമിലേക്ക് കടന്നു.

ഇതോടുകൂടി സാമൂഹികവും വ്യക്തിപരവും ആയി അവരിൽ പലരിലും വൻ ഔന്നിത്യം വന്നുതുടങ്ങി. വെളുത്ത ത്വക്കിൻ നിറത്തിലുള്ള അറബി രക്തപാതയും അവരിൽ കയറിത്തുടങ്ങി. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണമാണ് സ്ഥാപിതമായത് എന്നതിനാൽ ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷക്കാരായ നായർ മേധവികൾക്ക് അവരെ അടിച്ചു തമർത്താൻ ആയില്ല.

ഭരണം ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷുകാരുടേതാണ് എങ്കിലും ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷുകാരെ ആരേയും സാമൂഹത്തിൽ കാണാൻ ഇല്ലായിരുന്നു. എന്നുവച്ചാൽ സമൂഹം അന്നും ബ്രഹ്മണമേധവിത്വത്തിലും നായർമാരുടെ മേൽനോട്ടത്തിലും ആയി നിലനിന്നു.

കാലകാലങ്ങളായി കന്നുകാലികൾ ആയി നിലനിർത്തപ്പെട്ടിരുന്ന അടിമജനത്തിന് തമ്മിൽ സംഘടിക്കാൻ ആയിട്ടില്ല. ഇതിന്റെ ഏറ്റവും ശക്തമായ കാരണം, ആ പ്രദേശത്തിൽ ഉള്ള ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷതന്നെ.

മുകളിലുള്ളവരെ ആദരിക്കാനും, കൂടെയുള്ളവരെ അപമാനിക്കാനും തരംതാഴ്ത്താനും കൊച്ചാക്കി സംസാരിക്കാനും അസൂയയോടുകൂടി വീക്ഷിക്കാനും പിന്നിൽ നിന്നും കുത്താനും മറ്റും നിരന്തര പ്രേരണ നൽകുന്ന ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷയാണ് എല്ലാരും സംസാരിക്കുന്നത്.

ഇത്രയും വിനാശയകരമായതും എന്നാൽ വൻ സൗന്ദര്യം പാട്ടുകളിലൂടെ സൃഷ്ടിക്കാൻ ആവുന്നതുമായ പ്രാദേശിക ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷയുടെ യന്ത്രസംവിധാനത്തെ തടയാൻ ഒരു വൻ പരിധിവരെ ഇസ്ലാമിനു കഴിഞ്ഞു എന്നാണ് മനസ്സിലാക്കേണ്ടത്.

എന്നുവച്ചാൽ ഇസ്ലാം ഇല്ലാതെ ഈ കീഴ്ജന വ്യക്തികൾ സാമൂഹികമായി കയറൂരി നിൽക്കാൻ ശ്രമിച്ചാൽ, അവർ തുടക്കത്തിൽ തന്നെ തമ്മിൽ ഏറ്റുമുട്ടും. തമ്മിൽ വൻ സംശയത്തോടും, ഭീതിയോടും അസൂയയോടും വീക്ഷിച്ചും തമ്മിൽ പാരവച്ചും, തമ്മിൽ സ്ത്രീകളെ വശീകരിച്ച് അതുമായി ബന്ധപ്പെട്ട് അടിപിടികൂടിയും മറ്റുമായി അവർ സാമൂഹികമായി കെട്ടടങ്ങും.

അവരുടെ നാടോടി ഗാനങ്ങളിൽ അവർ അവരുടെ നായർ മേധാവികളുടെ വീര കഥകൾ പാടിപ്പാടി ഉല്ലസിക്കും. അവരുടെ ഇടയിലുള്ള ആരെങ്കിലും ബ്രാഹ്മണ മേധാവികളെക്കുറിച്ചോ അവരുടെ സ്ത്രീജനങ്ങളെക്കുറിച്ചോ എന്തെങ്കിലും അവഹേളന വാക്കുകൾ പറഞ്ഞാൽ അവരിൽ പലരും വൻ ധൃതിയോടുകൂടി ഇക്കാര്യം അവരുടെ നായർ മേധാവികളെ അറിയിക്കാൻ ഉത്സാഹം കാണിക്കും.

ഇങ്ങിനെയുള്ള ഒരു ജനതയിൽ വൻ സാഹോദര്യബോധവും സഹകരണ മാനസികാവസ്ഥയും ഐക്യവും കൊണ്ടുവന്നത് ഇസ്ലാം ആണ്.

ഇത് ഒരു ഭയങ്കര കാര്യം തന്നെയാണ്. ഉദാഹരണത്തിന് ബ്രാഹ്മണമതം ഈ രീതയിൽ പെരുമാറിയെന്നു കരുതുക.

അവർ അവരുടെ അടിമ ജനത്തിന് അവർ പൊന്നുപോലെ കൊണ്ടുനടന്ന ആദ്ധ്യാത്മിക പാരമ്പര്യങ്ങളും മറ്റും പഠിപ്പിക്കുകയും, ഈ കീഴ്ജനത്തിന് ബ്രാഹ്മണ പാരമ്പര്യത്തിലെ വരേണ്യവക്തികളുടെ പേരുകൾ ഉപയോഗിക്കാൻ അവകാശം നൽകുകയും മറ്റും ചെയ്താലുള്ള കാര്യം ആലോചിക്കുക.

പറമ്പിലെ കുപ്പത്തൊട്ടിപോലുള്ള ഇടങ്ങളിൽ നിലത്ത് ഇരിക്കുകയും കിടക്കുയും ചെയ്തിരുന്ന ജനവംശങ്ങൾക്ക് വീട്ടിനുള്ള വരാനും കസേരയിൽ ഇരിക്കാനും വൻ ദാർശനികാര്യങ്ങൾ ചർച്ചചെയ്യാനും സ്വന്തം വീട്ടിലെ ആളുകളെ വിളക്കാനും സംബോധന ചെയ്യാനും കൂടി ഈ ബ്രാഹ്മണർ അവസരം നൽകുകകൂടി ചെയ്തു എന്നു ചിന്തിക്കുക. ഭാഷ ഫ്യൂഡൽ സ്വഭാവമുള്ളതാണ് എന്ന കാര്യം മറക്കരുത്.

ഇന്നും സ്വന്തം വീട്ടിലെ അടുക്കള വേലക്കാരിക്ക് മിക്ക ഇന്ത്യൻ വീടുകളിലും കസേരയിൽ ഇരിക്കാൻ ആരും അനുവദിക്കില്ല.

ഇങ്ങിനെ അനുവദിച്ചാൽ വീട്ടിൽ എന്തോവിധ മാലിന്യം കയറിവരും എന്ന് ഏവർക്കും അറിയാം.

അതേ സമയം ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കമ്പനിയിലെ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥർക്ക് ഈ കാര്യത്തിന്റെ പൊരുൾ അത്രകണ്ട് മനസ്സിലായിക്കാണില്ല. ഒരാൾ അടിച്ചുവാരുന്ന തൊഴിൽ ചെയ്താൽ അയാൾക്ക് ഇരിപ്പിടം നൽകരുതാത്തത് എന്തുകൊണ്ടാണ് എന്ന് അവർക്ക് അറിയില്ല. പോരാത്തതിന്, അവർ അവരുടെ സ്വന്തം നാട്ടിൽ എല്ലാ വിധ തൊഴിലും ചെയ്യുകയും ചെയ്യുന്നവർ തന്നെ.

എന്നാൽ അവർക്കും മലബാറിലെ കീഴ്ജനത്തിനെ പിടിച്ച് കസേരയിൽ ഇരുത്താൻ ആവില്ല. അങ്ങിനെ അവർ ചെയ്താൽ, മലബാറിലെ ഉന്നത വ്യക്തികൾ അവരുടെ സ്ഥാപനങ്ങളിൽ കയറില്ല.

ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷം കീഴ്ജനത്തിനെ അവരുടെ പാരമ്പര്യ ആദ്ധ്യാത്മിക പ്രസ്ഥാനത്തിൽ കയറ്റിയാൽ ബ്രാഹ്മണ പ്രസ്ഥാനം മലിനപ്പെടും. പോരാത്തതിന്, ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷക്കാർക്ക് അവരുടെ എല്ലാവിധ പാരമ്പര്യ അവകാശങ്ങളും നഷ്ടമാകും. കയറിവന്ന കീഴ്ജനം അവരെ തുരത്തും. വാക്കുകളിൽ തരംതാഴ്ത്തും.

പോരാത്തതിന്, ബ്രഹ്മണ മതം തന്നെ വികലപ്പെടും. അത് ഒരു തരം തെമ്മാടി മതവും അടിപിടിക്കാരുടേയും ബഹളക്കാരുടേയും മതമായും മാറാം.

ഇത് സംഭാവ്യമായ ഒരു വാസ്തവം തന്നെയാണ്.

ഈ വീക്ഷണകോണിൽ നിന്നും നോക്കിയാൽ ഇസ്ലാം കീഴ്ജനത്തിനെ വളർത്തിയെടുക്കാൻ ശ്രമിച്ചത് ഒരു വൻ കാര്യം തന്നെയാണ്. ആലോചിച്ചാൽ സാമൂഹികമായി പലരിലും വിറയൽ തന്നെ വരുത്തിയേക്കാം.

കുറേകാലത്തേക്ക് മലബാറി മാപ്പിളമാരിൽ ഇസ്ലാമിന്റെ സ്വതസിദ്ധമായ ഭാവങ്ങൾക്ക് അതീതമായുള്ള ഒരു ഭീകര രൂപം ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നിരിക്കാം. ഈ കാര്യത്തെ ഇസ്ലാം മതത്തിന്റെ ഭീകരതയായി നിർവ്വചിക്കാൻ എളുപ്പമാണ്. എന്നാൽ വാസ്തവം മുകളിൽ സൂചിപ്പിച്ചതുതന്നെ.

കയറൂരിവടപ്പെട്ട കീഴ്ജനത്തിൽ വെളുത്ത ത്വക്കിൻ നിറത്തിലുള്ള അറബി രക്തപാതയും ഇസ്ലാമിക ആദ്ധ്യാത്മിക പരീശീലനങ്ങളും മറ്റും ലഭിച്ചത് കൊണ്ട് മാത്രം സമൂഹത്തിൽ സമാധാനം വരില്ല.

മറിച്ച് സമൂഹത്തിൽ ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷ ഇറക്കിവിടുന്ന ഭീകരതയ്ക്ക് ഒരു ആക്കം കൂട്ടൽ മാത്രമാണ് ഉണ്ടാവുക.

സമൂഹത്തിൽ ഈ മാപ്പിളമാർ മാത്രമല്ല ജീവിക്കുന്നത്. പാരമ്പര്യമായ ഒരു ഉച്ചനീചത്വ സാമൂഹിക ആന്തരീക്ഷവും നിലവിൽ ഉണ്ട്.

സംഘടിച്ചു നിൽക്കുന്ന കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാർക്ക് പലവിധ വിഷമങ്ങളും വിദ്വേഷങ്ങളും ഉണ്ട്. അവർ സമൂഹത്തിന്റെ പാരമ്പര്യ കീഴ്വഴക്കങ്ങളെ അനുസരിക്കാതെ സമൂഹത്തിൽ ജീവിക്കാനും തൊഴിൽ ചെയ്യാനും തുടങ്ങിയാൽ സമൂഹത്തിലെ മറ്റ് ജനവംശരിൽ വൻ വെപ്രാളം വരുത്തും എന്നത് വാസ്തവം തന്നെ.

ഇസ്ലാമിലേക്ക് കയറാത്ത മറ്റ് കീഴ്ജനം ഈ പുതിയ മാപ്പിളമാരെ വൻ നീരസത്തോടും ഭീതിയോടും വീക്ഷിക്കും. കാരണം, ഓരോ തലമുറ കഴിയുന്തോറും കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാരിൽ വൻ വ്യത്യസം വന്നതായി കാണും. അവർ പഴയ കീഴജന രക്തബന്ധ പാതയിൽ ഉള്ളവർ ആണ് എന്ന ബോധം തന്നെ മാഞ്ഞുതുടങ്ങും.

നായർമർക്കും പ്രശ്നം തന്നെയാണ്. അവർക്ക് സാമൂഹികമായി ചില മേൽനോട്ട അവകാശം ഉണ്ട്. അത് അവരുടെ തലയെടുപ്പിന്റെ ഭാഗമായി അവർ കൊണ്ടുനടക്കും. എന്നാൽ അവരെ വകവെക്കാത്ത ഒരു കൂട്ടർ ആണ് ഈ പുതിയ മാപ്പിളമാർ.

ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷു പോലുള്ള ഒരു ഭാഷയല്ല പ്രാദേശിക ഭാഷ. ഓരോ വാക്കിലും വിധേയത്വം അല്ലെങ്കിൽ അതിന്റെ നേരെ വിപരീതമായ ധാർഷ്ട്യം നിർബന്ധമായും പ്രത്യക്ഷപ്പെടും. വിധേയത്വം മര്യാദയായും ധാർഷ്ട്യം ആക്രമണമായും മനസ്സിലാക്കപ്പെടും.

ഇത് കണ്ടില്ലായെന്നും കേട്ടില്ലായെന്നും ഒന്നും നടിക്കാൻ ആവില്ല. കണ്ണും ചെവിയും ഉള്ളർ ഈ വാക്കുകളുടെ കോഡുകൾക്ക് വിധേയരായി പ്രതിപ്രർത്തിക്കും. പ്രതികരിക്കും.

ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് പക്ഷവും ലോകത്തിന്റെ പലദിക്കിലും കീഴ്ജന വ്യക്തികളെ വളർത്തിക്കൊണ്ട് വന്നിട്ടുണ്ട്. എന്നാൽ അത് മറ്റൊരു രീതിയിൽ ആണ്. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭാഷ പഠിപ്പിക്കുകയും ആ ഭാഷ സംസാരിപ്പിക്കുകയും ചെയ്യുമ്പോൾ, പ്രാദേശിക ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷകളുടെ അടിമപ്പെടുത്തലുകളിൽ നിന്നും വ്യക്തികൾ സ്വാഭാവികമായി മോചിതരാകും. മറ്റുള്ളവരിൽ വേദനയോ വിരോധമോ പ്രകോപനമോ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭാഷാ വാക്കുകൾ സാധാരണയായി വളർത്തില്ല. (എന്നാൽ ഇതിനെക്കുറിച്ച് ചിലത് പറയാനുണ്ട്. പിന്നീടെപ്പോഴെങ്കിലും ആവാം അത്).

ഈ ഒരു കാര്യം ഇസ്ലാമിന് ചെയ്യാനായിട്ടില്ല. എന്നാൽ ചെയ്തകാര്യം വൻ കാര്യം തന്നെയാണ്. എന്നാൽ സമൂഹത്തിൽ മറ്റൊരു ഭീകരാവസ്ഥയാണ് സംജാതമായത്. അതിന്റെ കാരണവരും കണ്ടത്തേണ്ടതുണ്ട്.

ഇന്നത്തെ പാലസ്തീൻകാരുടെ സ്വാതന്ത്ര്യ സമരത്തെക്കുറിച്ച് ആലോചിക്കാം. അവരുടെ ഭാഷ അറബിയാണ് എന്നു തോന്നുന്നു.

പാലസ്തീനിൽ ഇന്ത്യാക്കാരും മറ്റ് ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷക്കാരും കാര്യമായി ഇല്ലാ എന്നാണ് തോന്നുന്നത്.

ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷക്കാരുടെ സാന്നിദ്ധ്യത്തെക്കുറിച്ച് പറഞ്ഞതിന്റെ കാര്യം ഇതാണ്:

ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷക്കാരുടെ സാന്നിദ്ധ്യം ഉണ്ട് എങ്കിൽ അത് അറബി ഭാഷയേയും സ്വാധീനിക്കും. പോരാത്തതിന് അത് ആഭാഷയെ ഒരു പരിധിവരെ വികലപ്പെടുത്തുകയും ചെയ്തേക്കാം. ഈ പറഞ്ഞത് വെറും ഒരു ഊഹോപോഹം മാത്രമാണ്. കാരണം, ഈ എഴുത്തുകാരന് അറബി അറിയില്ല.

എന്നിരുന്നാലും, ഭാഷകോഡുകളിൽ മാനസികമായി മലമുകളിൽ ഉള്ളവരേയും, കുഴിയിൽ പെട്ടുകിടക്കുന്നവരേയും അറബി ഭാഷ വ്യത്യസ്തരായി അഭിമുഖീകരിക്കുമ്പോൾ, ആ ഭാഷയിലെ നൈസർഗികമായ വാക്ക് കോഡുകൾക്ക് ഒരു പര്യാപ്തതക്കുറവ് അനുഭവപ്പെട്ടേക്കാം. പോരാത്തതിന്, ഈ കൂട്ടർ അറബി ജനത്തിനേയും നിർവ്വചിക്കുന്ന അനുഭവവും അറബി പക്ഷക്കാരിൽ ചെറിയ തോതിലുള്ള ഭാവപ്പകർച്ചകൾ സൃഷ്ടിച്ചേക്കാം. അതും ഭാഷാ വാക്ക്കോഡുകളിൽ മാറ്റം വരുത്തിയേക്കാം.

ഇനി പാലസ്ത്തീൻകാരുടെ കാര്യം. അവരുടെ ഭാഷ മലയാളം, തമിഴ്, ഹിന്ദി തുടങ്ങിയ ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷകളെപ്പോലെയാണ് എങ്കിൽ ആ ജനതയ്ക്ക് ഒറ്റക്കെട്ടായുള്ള ഒരു ചെറുത്ത് നിൽപ്പ് ആവില്ലതന്നെ. ആവുമെങ്കിൽതന്നെ അവയെല്ലാം വളരെ വേഗത്തിൽ പല ഗ്രൂപ്പുകളായി ചിന്നിച്ചിതറുമായിരുന്നു.

പോരാത്തതിന്, ഇസ്റേലി ആക്രമണങ്ങളിൽ വീടുകളും മറ്റും നഷ്ടപ്പെട്ടാൽ വ്യക്തികൾക്ക് തമ്മിൽ സംസാരിക്കാൻ തന്നെ പ്രയാസം നേരിടും. കാരണം, മുകളിൽ സൂചിപ്പിച്ച ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷാ ആശയവിനിമയത്തിൽ വീടിന്റെ മഹിമ ഒരു പ്രധാന ഘടകമാണ്. വീട് തരിപ്പണമായാൽ, വ്യക്തിയും വാക്ക് കോഡുകളിൽ തരിപ്പണമായിപ്പോകും.

അറബി ഭാഷാ വാക്ക്കോഡുകൾ തമ്മിൽ തെറ്റിക്കാതെ നിർത്തുന്ന അവിടുള്ള ജനത്തിന് ഇസ്ലാം കൂടുതലായുള്ള ഒരു ഐക്യബോധം വരുത്തുന്നുണ്ട് എന്നത് ശരിയാണ് എങ്കിലും, മറ്റ് ഇസ്ലാം രാഷ്ട്രങ്ങൾ മിക്കവയും പാലസ്ത്തീകാരുടെ പ്രശ്നത്തിൽ ഒരു തണുപ്പൻ പ്രതികരണമാണ് നൽകിയത് എന്നും ഓർക്കുക.

ബൃട്ടിഷ്-ഇന്ത്യയെ Clement Atlee നെഹ്റുപക്ഷത്തിന് നൽകുകയും ആ കൂട്ടർ ഒരു ഹിന്ദി ഇംപീരിയലിസം ഈ ഉപഭൂഖണ്ഡത്തിൽ നടപ്പിലാക്കാൻ ശ്രമിക്കുകയും ചെയ്തപ്പോൾ, ബൃട്ടിഷ്-ഇന്ത്യയിൽ എല്ലായിടത്തും സാമൂഹികമായി ഉന്നതരായുള്ള വ്യക്തികൾ പുതിയ ഭരണപ്രസ്ഥാനത്തിൽ പിടിച്ചുകയറാനും സ്വന്തം പ്രദേശത്തുള്ള മറ്റുവ്യക്തികളെ പിന്നിലാക്കാനും ആണ് വെപ്രാളപ്പെട്ടും ധൃതിപിടിച്ചും ശ്രമിച്ചത്.

കുറച്ചുകൂടി വ്യക്തമായി പറഞ്ഞാൽ, ബൃട്ടിഷ്-മലബാറിൽ കുറച്ച് വകതിരുവുള്ള ഏതൊരു വ്യക്തിക്കും മനസ്സിലാക്കുവന്നതേയുള്ള, ഈ പ്രദേശം ചരിത്രത്തിൽ ഒരിക്കൽ പോലും ഹിന്ദിക്കാരുടെ കീഴിൽ വരാത്ത പ്രദേശമാണ് എന്ന്. പോരാത്തതിന്, മലബാറി ഭാഷയിൽ സംസ്കൃതവാക്കുകൾ പോലും വളരെ നിസ്സാരമായേ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നുള്ളു.

അതേ സമയം സംസ്കൃത വാക്കുകൾ മിക്ക ദക്ഷിണേഷ്യൻ ഭാഷകളിലും അടുത്തകാലത്ത് കൂട്ടിച്ചേർത്തവ മാത്രമാണ് എന്നതും ഇവിടെ പ്രസ്താവ്യമാണ്. ഈ സംസ്കൃത ഭാഷാ വാക്കുകൾ ഈ ഉപഭൂഖണ്ഡത്തിലെ ഭാഷകളിൽ നിന്നും മാച്ചുകളഞ്ഞാൽ, ഇന്നുള്ള ഇന്ത്യയെന്ന സങ്കൽപ്പം തന്നെ നിർവ്വീര്യമാകും.

മലബാറുകാർക്ക് തമ്മിൽ സംഘടിക്കാനും സഹകരിക്കാനും ആവുന്ന ഭാഷയല്ല പ്രാദേശിക ഭാഷ. എന്നാൽ ഉപഭൂഖണ്ഡത്തിന്റെ വടക്കൻ പ്രദേശങ്ങളിലെ രാഷ്ടീയ നേതാക്കളുടെ പേരിന് കീഴിൽ അണിനിരന്നാൽ ഒരു കൃത്രിമമായിട്ടുള്ള ഐക്യബോധം കൈവരും. ഇതാണ് ബൃട്ടിഷ്-മലബാറിനെ ഹിന്ദി ഇംപീരിയലിസത്തിന് കീഴിൽ എത്തിച്ചത്.

ഈ വിഷയത്തെക്കുറിച്ച് ഇവിടെ കൂടുതലായുള്ള വിശകലനത്തിന് പോകുന്നില്ല. എന്നാൽ ഇതിൽ നിന്നും ചില കാര്യങ്ങൾ മലബാറിലെ മാപ്പിള ആക്രമണ പ്രശ്നത്തിലേക്ക് വലിച്ചെടുക്കുകയാണ്. അവ പൂർണ്ണമായും മലബാറിൽ ശരിയാവണമെന്നില്ല.

എന്നാൽ നോക്കൂ:

മൈസൂറുകാരുടെ ആക്രമണം പല കീഴ്ജന വ്യക്തികൾക്കും അവരുടെ കന്നുകാലി നിലവാരത്തിലുള്ള അടിമ അവസ്ഥയിൽ നിന്നും രക്ഷപ്പെടാൻ സൗകര്യം നൽകി. അവരിൽ പലരും ഇസ്ലാമിലേക്ക് കടന്നു.

ഇതോടുകൂടി സാമൂഹികവും വ്യക്തിപരവും ആയി അവരിൽ പലരിലും വൻ ഔന്നിത്യം വന്നുതുടങ്ങി. വെളുത്ത ത്വക്കിൻ നിറത്തിലുള്ള അറബി രക്തപാതയും അവരിൽ കയറിത്തുടങ്ങി. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണമാണ് സ്ഥാപിതമായത് എന്നതിനാൽ ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷക്കാരായ നായർ മേധവികൾക്ക് അവരെ അടിച്ചു തമർത്താൻ ആയില്ല.

ഭരണം ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷുകാരുടേതാണ് എങ്കിലും ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷുകാരെ ആരേയും സാമൂഹത്തിൽ കാണാൻ ഇല്ലായിരുന്നു. എന്നുവച്ചാൽ സമൂഹം അന്നും ബ്രഹ്മണമേധവിത്വത്തിലും നായർമാരുടെ മേൽനോട്ടത്തിലും ആയി നിലനിന്നു.

കാലകാലങ്ങളായി കന്നുകാലികൾ ആയി നിലനിർത്തപ്പെട്ടിരുന്ന അടിമജനത്തിന് തമ്മിൽ സംഘടിക്കാൻ ആയിട്ടില്ല. ഇതിന്റെ ഏറ്റവും ശക്തമായ കാരണം, ആ പ്രദേശത്തിൽ ഉള്ള ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷതന്നെ.

മുകളിലുള്ളവരെ ആദരിക്കാനും, കൂടെയുള്ളവരെ അപമാനിക്കാനും തരംതാഴ്ത്താനും കൊച്ചാക്കി സംസാരിക്കാനും അസൂയയോടുകൂടി വീക്ഷിക്കാനും പിന്നിൽ നിന്നും കുത്താനും മറ്റും നിരന്തര പ്രേരണ നൽകുന്ന ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷയാണ് എല്ലാരും സംസാരിക്കുന്നത്.

ഇത്രയും വിനാശയകരമായതും എന്നാൽ വൻ സൗന്ദര്യം പാട്ടുകളിലൂടെ സൃഷ്ടിക്കാൻ ആവുന്നതുമായ പ്രാദേശിക ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷയുടെ യന്ത്രസംവിധാനത്തെ തടയാൻ ഒരു വൻ പരിധിവരെ ഇസ്ലാമിനു കഴിഞ്ഞു എന്നാണ് മനസ്സിലാക്കേണ്ടത്.

എന്നുവച്ചാൽ ഇസ്ലാം ഇല്ലാതെ ഈ കീഴ്ജന വ്യക്തികൾ സാമൂഹികമായി കയറൂരി നിൽക്കാൻ ശ്രമിച്ചാൽ, അവർ തുടക്കത്തിൽ തന്നെ തമ്മിൽ ഏറ്റുമുട്ടും. തമ്മിൽ വൻ സംശയത്തോടും, ഭീതിയോടും അസൂയയോടും വീക്ഷിച്ചും തമ്മിൽ പാരവച്ചും, തമ്മിൽ സ്ത്രീകളെ വശീകരിച്ച് അതുമായി ബന്ധപ്പെട്ട് അടിപിടികൂടിയും മറ്റുമായി അവർ സാമൂഹികമായി കെട്ടടങ്ങും.

അവരുടെ നാടോടി ഗാനങ്ങളിൽ അവർ അവരുടെ നായർ മേധാവികളുടെ വീര കഥകൾ പാടിപ്പാടി ഉല്ലസിക്കും. അവരുടെ ഇടയിലുള്ള ആരെങ്കിലും ബ്രാഹ്മണ മേധാവികളെക്കുറിച്ചോ അവരുടെ സ്ത്രീജനങ്ങളെക്കുറിച്ചോ എന്തെങ്കിലും അവഹേളന വാക്കുകൾ പറഞ്ഞാൽ അവരിൽ പലരും വൻ ധൃതിയോടുകൂടി ഇക്കാര്യം അവരുടെ നായർ മേധാവികളെ അറിയിക്കാൻ ഉത്സാഹം കാണിക്കും.

ഇങ്ങിനെയുള്ള ഒരു ജനതയിൽ വൻ സാഹോദര്യബോധവും സഹകരണ മാനസികാവസ്ഥയും ഐക്യവും കൊണ്ടുവന്നത് ഇസ്ലാം ആണ്.

ഇത് ഒരു ഭയങ്കര കാര്യം തന്നെയാണ്. ഉദാഹരണത്തിന് ബ്രാഹ്മണമതം ഈ രീതയിൽ പെരുമാറിയെന്നു കരുതുക.

അവർ അവരുടെ അടിമ ജനത്തിന് അവർ പൊന്നുപോലെ കൊണ്ടുനടന്ന ആദ്ധ്യാത്മിക പാരമ്പര്യങ്ങളും മറ്റും പഠിപ്പിക്കുകയും, ഈ കീഴ്ജനത്തിന് ബ്രാഹ്മണ പാരമ്പര്യത്തിലെ വരേണ്യവക്തികളുടെ പേരുകൾ ഉപയോഗിക്കാൻ അവകാശം നൽകുകയും മറ്റും ചെയ്താലുള്ള കാര്യം ആലോചിക്കുക.

പറമ്പിലെ കുപ്പത്തൊട്ടിപോലുള്ള ഇടങ്ങളിൽ നിലത്ത് ഇരിക്കുകയും കിടക്കുയും ചെയ്തിരുന്ന ജനവംശങ്ങൾക്ക് വീട്ടിനുള്ള വരാനും കസേരയിൽ ഇരിക്കാനും വൻ ദാർശനികാര്യങ്ങൾ ചർച്ചചെയ്യാനും സ്വന്തം വീട്ടിലെ ആളുകളെ വിളക്കാനും സംബോധന ചെയ്യാനും കൂടി ഈ ബ്രാഹ്മണർ അവസരം നൽകുകകൂടി ചെയ്തു എന്നു ചിന്തിക്കുക. ഭാഷ ഫ്യൂഡൽ സ്വഭാവമുള്ളതാണ് എന്ന കാര്യം മറക്കരുത്.

ഇന്നും സ്വന്തം വീട്ടിലെ അടുക്കള വേലക്കാരിക്ക് മിക്ക ഇന്ത്യൻ വീടുകളിലും കസേരയിൽ ഇരിക്കാൻ ആരും അനുവദിക്കില്ല.

ഇങ്ങിനെ അനുവദിച്ചാൽ വീട്ടിൽ എന്തോവിധ മാലിന്യം കയറിവരും എന്ന് ഏവർക്കും അറിയാം.

അതേ സമയം ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കമ്പനിയിലെ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥർക്ക് ഈ കാര്യത്തിന്റെ പൊരുൾ അത്രകണ്ട് മനസ്സിലായിക്കാണില്ല. ഒരാൾ അടിച്ചുവാരുന്ന തൊഴിൽ ചെയ്താൽ അയാൾക്ക് ഇരിപ്പിടം നൽകരുതാത്തത് എന്തുകൊണ്ടാണ് എന്ന് അവർക്ക് അറിയില്ല. പോരാത്തതിന്, അവർ അവരുടെ സ്വന്തം നാട്ടിൽ എല്ലാ വിധ തൊഴിലും ചെയ്യുകയും ചെയ്യുന്നവർ തന്നെ.

എന്നാൽ അവർക്കും മലബാറിലെ കീഴ്ജനത്തിനെ പിടിച്ച് കസേരയിൽ ഇരുത്താൻ ആവില്ല. അങ്ങിനെ അവർ ചെയ്താൽ, മലബാറിലെ ഉന്നത വ്യക്തികൾ അവരുടെ സ്ഥാപനങ്ങളിൽ കയറില്ല.

ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷം കീഴ്ജനത്തിനെ അവരുടെ പാരമ്പര്യ ആദ്ധ്യാത്മിക പ്രസ്ഥാനത്തിൽ കയറ്റിയാൽ ബ്രാഹ്മണ പ്രസ്ഥാനം മലിനപ്പെടും. പോരാത്തതിന്, ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷക്കാർക്ക് അവരുടെ എല്ലാവിധ പാരമ്പര്യ അവകാശങ്ങളും നഷ്ടമാകും. കയറിവന്ന കീഴ്ജനം അവരെ തുരത്തും. വാക്കുകളിൽ തരംതാഴ്ത്തും.

പോരാത്തതിന്, ബ്രഹ്മണ മതം തന്നെ വികലപ്പെടും. അത് ഒരു തരം തെമ്മാടി മതവും അടിപിടിക്കാരുടേയും ബഹളക്കാരുടേയും മതമായും മാറാം.

ഇത് സംഭാവ്യമായ ഒരു വാസ്തവം തന്നെയാണ്.

ഈ വീക്ഷണകോണിൽ നിന്നും നോക്കിയാൽ ഇസ്ലാം കീഴ്ജനത്തിനെ വളർത്തിയെടുക്കാൻ ശ്രമിച്ചത് ഒരു വൻ കാര്യം തന്നെയാണ്. ആലോചിച്ചാൽ സാമൂഹികമായി പലരിലും വിറയൽ തന്നെ വരുത്തിയേക്കാം.

കുറേകാലത്തേക്ക് മലബാറി മാപ്പിളമാരിൽ ഇസ്ലാമിന്റെ സ്വതസിദ്ധമായ ഭാവങ്ങൾക്ക് അതീതമായുള്ള ഒരു ഭീകര രൂപം ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നിരിക്കാം. ഈ കാര്യത്തെ ഇസ്ലാം മതത്തിന്റെ ഭീകരതയായി നിർവ്വചിക്കാൻ എളുപ്പമാണ്. എന്നാൽ വാസ്തവം മുകളിൽ സൂചിപ്പിച്ചതുതന്നെ.

കയറൂരിവടപ്പെട്ട കീഴ്ജനത്തിൽ വെളുത്ത ത്വക്കിൻ നിറത്തിലുള്ള അറബി രക്തപാതയും ഇസ്ലാമിക ആദ്ധ്യാത്മിക പരീശീലനങ്ങളും മറ്റും ലഭിച്ചത് കൊണ്ട് മാത്രം സമൂഹത്തിൽ സമാധാനം വരില്ല.

മറിച്ച് സമൂഹത്തിൽ ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷ ഇറക്കിവിടുന്ന ഭീകരതയ്ക്ക് ഒരു ആക്കം കൂട്ടൽ മാത്രമാണ് ഉണ്ടാവുക.

സമൂഹത്തിൽ ഈ മാപ്പിളമാർ മാത്രമല്ല ജീവിക്കുന്നത്. പാരമ്പര്യമായ ഒരു ഉച്ചനീചത്വ സാമൂഹിക ആന്തരീക്ഷവും നിലവിൽ ഉണ്ട്.

സംഘടിച്ചു നിൽക്കുന്ന കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാർക്ക് പലവിധ വിഷമങ്ങളും വിദ്വേഷങ്ങളും ഉണ്ട്. അവർ സമൂഹത്തിന്റെ പാരമ്പര്യ കീഴ്വഴക്കങ്ങളെ അനുസരിക്കാതെ സമൂഹത്തിൽ ജീവിക്കാനും തൊഴിൽ ചെയ്യാനും തുടങ്ങിയാൽ സമൂഹത്തിലെ മറ്റ് ജനവംശരിൽ വൻ വെപ്രാളം വരുത്തും എന്നത് വാസ്തവം തന്നെ.

ഇസ്ലാമിലേക്ക് കയറാത്ത മറ്റ് കീഴ്ജനം ഈ പുതിയ മാപ്പിളമാരെ വൻ നീരസത്തോടും ഭീതിയോടും വീക്ഷിക്കും. കാരണം, ഓരോ തലമുറ കഴിയുന്തോറും കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാരിൽ വൻ വ്യത്യസം വന്നതായി കാണും. അവർ പഴയ കീഴജന രക്തബന്ധ പാതയിൽ ഉള്ളവർ ആണ് എന്ന ബോധം തന്നെ മാഞ്ഞുതുടങ്ങും.

നായർമർക്കും പ്രശ്നം തന്നെയാണ്. അവർക്ക് സാമൂഹികമായി ചില മേൽനോട്ട അവകാശം ഉണ്ട്. അത് അവരുടെ തലയെടുപ്പിന്റെ ഭാഗമായി അവർ കൊണ്ടുനടക്കും. എന്നാൽ അവരെ വകവെക്കാത്ത ഒരു കൂട്ടർ ആണ് ഈ പുതിയ മാപ്പിളമാർ.

ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷു പോലുള്ള ഒരു ഭാഷയല്ല പ്രാദേശിക ഭാഷ. ഓരോ വാക്കിലും വിധേയത്വം അല്ലെങ്കിൽ അതിന്റെ നേരെ വിപരീതമായ ധാർഷ്ട്യം നിർബന്ധമായും പ്രത്യക്ഷപ്പെടും. വിധേയത്വം മര്യാദയായും ധാർഷ്ട്യം ആക്രമണമായും മനസ്സിലാക്കപ്പെടും.

ഇത് കണ്ടില്ലായെന്നും കേട്ടില്ലായെന്നും ഒന്നും നടിക്കാൻ ആവില്ല. കണ്ണും ചെവിയും ഉള്ളർ ഈ വാക്കുകളുടെ കോഡുകൾക്ക് വിധേയരായി പ്രതിപ്രർത്തിക്കും. പ്രതികരിക്കും.

ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് പക്ഷവും ലോകത്തിന്റെ പലദിക്കിലും കീഴ്ജന വ്യക്തികളെ വളർത്തിക്കൊണ്ട് വന്നിട്ടുണ്ട്. എന്നാൽ അത് മറ്റൊരു രീതിയിൽ ആണ്. ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭാഷ പഠിപ്പിക്കുകയും ആ ഭാഷ സംസാരിപ്പിക്കുകയും ചെയ്യുമ്പോൾ, പ്രാദേശിക ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷകളുടെ അടിമപ്പെടുത്തലുകളിൽ നിന്നും വ്യക്തികൾ സ്വാഭാവികമായി മോചിതരാകും. മറ്റുള്ളവരിൽ വേദനയോ വിരോധമോ പ്രകോപനമോ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭാഷാ വാക്കുകൾ സാധാരണയായി വളർത്തില്ല. (എന്നാൽ ഇതിനെക്കുറിച്ച് ചിലത് പറയാനുണ്ട്. പിന്നീടെപ്പോഴെങ്കിലും ആവാം അത്).

ഈ ഒരു കാര്യം ഇസ്ലാമിന് ചെയ്യാനായിട്ടില്ല. എന്നാൽ ചെയ്തകാര്യം വൻ കാര്യം തന്നെയാണ്. എന്നാൽ സമൂഹത്തിൽ മറ്റൊരു ഭീകരാവസ്ഥയാണ് സംജാതമായത്. അതിന്റെ കാരണവരും കണ്ടത്തേണ്ടതുണ്ട്.

Last edited by VED on Sun Jun 15, 2025 11:29 am, edited 1 time in total.

3. എഴുത്തിന്റെ ഒഴുക്കിലേക്ക് വീണ്ടും

ഏറ്റവും ഒടുവിലത്തെ എഴുത്ത് 2021 മെയ് മാസത്തിലാണ് പ്രക്ഷേപണം ചെയ്തത് എന്നു തോന്നുന്നു. ഇന്ന് ഇപ്പോൾ നവംമ്പർ മാസം 18 ആണ്.

എഴുതിക്കൊണ്ടിരുന്ന വിഷയം ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിൽ നടമാടിയ മാപ്പിള ലഹളയെന്ന് വിശേഷിപ്പിക്കപ്പെടുന്ന ചരിത്ര സംഭവം ആയിരുന്നു. അന്ന് എഴുതുന്ന അവസരത്തിൽ കാര്യങ്ങൾ മനസ്സിൽ ഒരു അരുവി കണക്കെ ഒഴുകി വന്നിരുന്നു. എന്നാൽ ഇന്ന് ഇപ്പോൾ മനസ്സിൽ നോക്കുമ്പോൾ ആ അരുവിയുടെ യാതോരു അംശവും കാണുന്നില്ല.

അന്ന് എന്തൊക്കെയാണ് എഴുതാനിരുന്നത് എന്നതുതന്നെ വിസ്മൃയിൽ മാഞ്ഞുപോയിരിക്കുന്നു.

എന്നാലും എഴുത്തിന്റെ ഒഴുക്കിലേക്ക് പിടിച്ചുകയറാൻ ശ്രമിക്കുകയാണ്.

മാപ്പിള ലഹളയെക്കുറിച്ച് പ്രാദേശിക ഇസ്ലാമിക പണ്ഡിതർ ഏതുവിധത്തിലാണ് മനസ്സിലാക്കിയത് എന്ന് ഈ എഴുത്തുകാരന് അറിയില്ല. എന്നിരുന്നാലും ഡോക്ട്രൽ തീസുസുകളായി സമർപ്പിക്കപ്പെട്ട ചില എഴുത്തുകൾ ഇപ്പോൾ കൺമുൻപിൽ ഉണ്ട്.

ഈ വിധ എഴുത്തുകൾക്ക് ഒരു വൻ പാളിച്ചയായി കാണപ്പെടുന്ന കാര്യങ്ങളിൽ ഒന്ന് ഇസ്ലാമിന്റേയോ അതുമല്ലെങ്കിൽ മുഹമ്മദിന്റേയോ ഏറ്റവും ഉജ്ജ്വല ആശയമായ സാമൂഹികമായും വ്യക്തിത്വപരമായും വ്യക്തികൾക്ക് ഒരു പരന്ന രീതിയിലുള്ളതും ഉന്നതനിലവാരത്തിലുള്ളതുമായ വ്യക്തിത്വവും അന്തസും എന്ന കാഴ്ചപ്പാടിനെ തീസിസ് പണ്ഡിതർക്ക് കാണാൻ പറ്റിയിട്ടില്ലാ എന്നതാണ് എന്നു തോന്നുന്നു.

മറ്റൊന്ന് പ്രാദേശിക സാമൂഹിക അന്തരീക്ഷത്തിലെ ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷ എന്ന രാക്ഷസീയ വസ്തുവിന്റെ അസ്തിത്വത്തെക്കുറിച്ച് യാതോരു അവബോധവും ഇല്ലാ എന്നുള്ളതാണ്.

പോരാത്തതിന്, മലബാറുകളിലും ദക്ഷിണേഷ്യയിൽ മുഴുവനായും ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണം എന്ന അതിഗംഭീര ചരിത്ര സംവഭത്തെ ഒരു ഉന്നത നിലവാരത്തിൽ നിന്നുകൊണ്ട് മനസ്സിലാക്കാനോ സമീപിക്കാനോ ആയില്ല എന്നുള്ളതും ഒരു പൊതുവായുള്ള പോരായ്മയായി നിലനിൽക്കുന്നുണ്ട്.

സാമൂഹികമായി എന്തിന്റെയൊക്കെയോ അടിയിൽ നിന്നുകൊണ്ടാണ് ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണത്തെ വിലയിരുത്താൻ പലരും ഒരുമ്പിടുന്നത്.

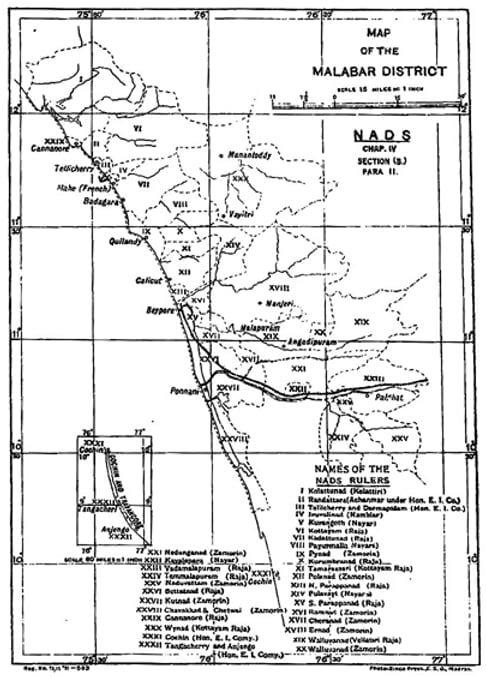

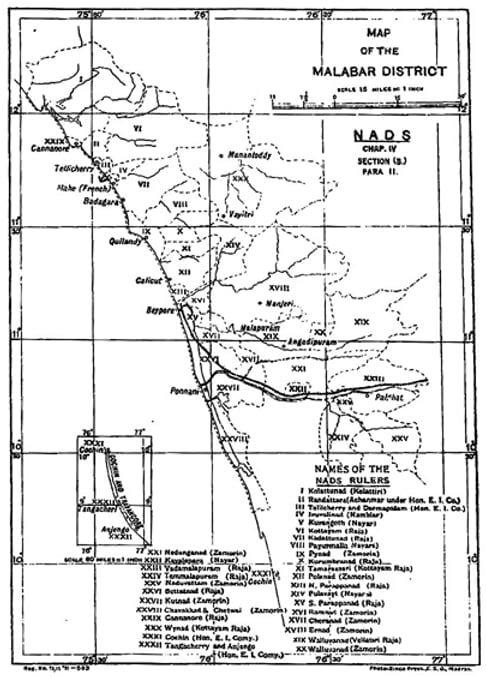

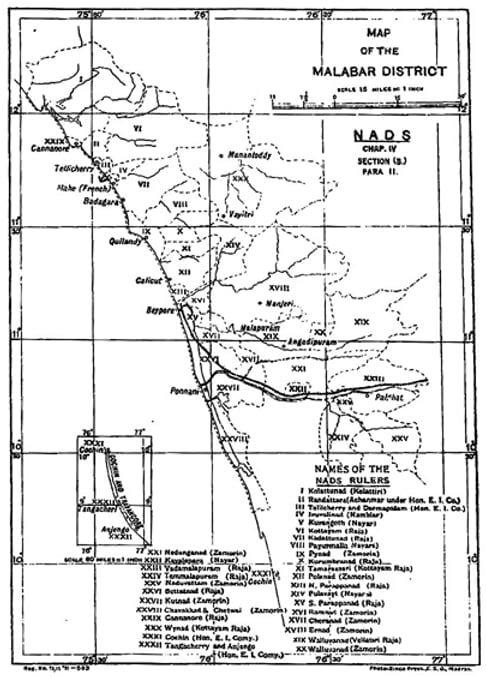

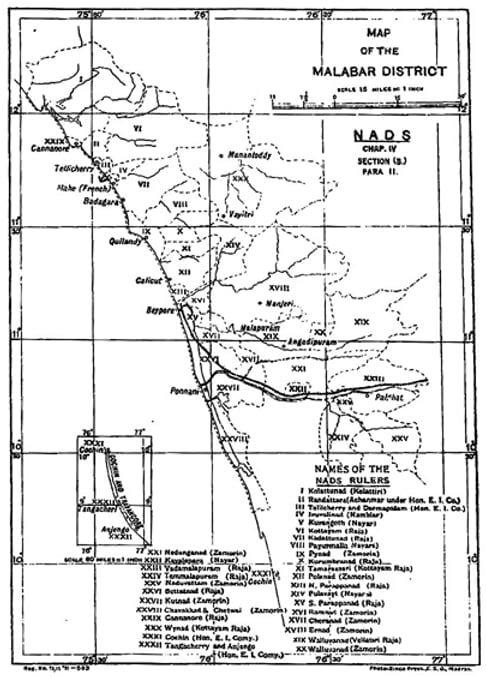

തീസുസുകൾ എഴുതുന്ന പണ്ഡിതർക്ക് ഇന്നുള്ള ഇന്ത്യ അന്നില്ലായിരുന്നുവെന്നോ, ഇന്ന് കാണുന്ന കേരളം അന്നില്ലായിരുന്നുവെന്നോ അറിവ് ലഭിക്കാത്ത ഒരു ഭാവവും കാണുന്നുണ്ട്. ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിലും ഉത്തര മലബാറിലും മൊത്തമായി 29 ഓളം വളരെ ചെറിയ രാജ്യങ്ങളോ അതുപോലുള്ള പ്രദേശങ്ങളോ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു. ഇവയെ എല്ലാം ചേർത്തെടുത്ത് മെഡ്രാസ് പ്രസിഡൻയിലെ ഒരു ഒറ്റ ജില്ലയാക്കുകയും അതിന് ശേഷം, അവിടങ്ങളിൽ ജനാധിപത്യമെന്ന ഭരണ സംവിധാനം നടപ്പാക്കിയതും ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണം ആണ്.

ഈ വിധമായുള്ള ഒരു അതി നൂതനമായി ചരിത്ര സംഭവം നടന്നപ്പോൾ, അവിടെ ജീവിച്ചിരുന്ന എല്ലാ ജന വംശങ്ങളിലും പലവിധ ഏറ്റക്കുറിച്ചലുകളും പൊളിച്ചെഴുത്തുകളും മറ്റും സംഭവിച്ചിരുന്നു. പല പാരമ്പര്യ ഉന്നത ജനക്കൂട്ടങ്ങളിൽ വൻ വെപ്രാളം തന്നെ സംഭവിച്ചിരുന്നു.

ഈ വെപ്രാളം ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷുകാർ അവരുടെ വീടുകളിൽ കയറും എന്നും അവരുടെ സമ്പത്തും സ്ത്രീജനങ്ങളേയും കൈവശപ്പെടുത്തും എന്നതായിരുന്നില്ല. മറിച്ച്, പാരമ്പര്യമായി അവരേക്കാൾ കീഴിൽ നിലനിന്നിരുന്ന ജനക്കൂട്ടങ്ങൾ സാമൂഹികമായി വളരും എന്നും അവർ തങ്ങളുടെ സാമൂഹിക സ്ഥാനങ്ങളും സ്വത്തുക്കളും കൈവശപ്പെടുത്തുമെന്നും തങ്ങളെ വാക്കുകളിലെ മഹത് സ്ഥാനങ്ങളിൽനിന്നും അവർ കുടിയിറക്കും എന്ന വെപ്രാളം തന്നെയായിരുന്നു.

ഇവിടേയും മനസ്സിലാക്കേണ്ടത്, പല കീഴ്ജനങ്ങളും ഇസ്ലാമിലേക്ക് കയറയിരുന്നു എന്നത് ശരിയാണ് എങ്കിൽ കൂടി, പാരമ്പര്യമായി സാമൂഹിക മഹിമയിൽ ജീവിച്ചിരുന്ന ഇസ്ലാമിക കുടുംബങ്ങളും മലബാറുകളിൽ അന്ന് ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു.

H.V. Connolly എന്ന ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷുകാരനായ മലബാർ ജീല്ലാ കലക്ടർ യഥാർത്ഥത്തിൽ മാപ്പിളമാരോട് പൊതുവായും കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാരോടു പ്രത്യേകമായും അനുകമ്പയുള്ള വ്യക്തിയാണ് എന്ന ഒരു ആരോപണം തന്നെ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണം മാപ്പിള സങ്കർഷങ്ങളെക്കുറിച്ച് പഠിക്കാൻ നിയോഗിച്ച Mr. Strange എന്ന ന്യായാധിപൻ പുറപ്പെടുവിച്ചിരുന്നു.

എന്നാൽ H.V. Connollyയെ ഏതാനും തെമ്മാടി വ്യക്തികൾ വെട്ടികൊലപ്പെടുത്തിയത് ഇസ്ലാമിക പ്രവർത്തനമായുള്ള ഒരു വൻ അഹ്ളാദകരമായ സംഭവം എന്ന രീതിയിൽ ആണ് തീസിസുകാർ എഴുതിക്കാണുന്നത്. ഈ വിധ വിഡ്ഢി പ്രവർത്തനത്തവുമായി ചെറിയ തോതിലെങ്കിലും മൗലിക ഇസ്ലാമിനെക്കുറിച്ച് വകതിരിവള്ള വ്യക്തികൾ ഇസ്ലാമിനെകൂട്ടിക്കലർത്താൻ ശ്രമിക്കും എന്ന് തോന്നുന്നില്ല.

ദക്ഷിണേഷ്യയിൽ അന്യാദൃശ്യമായ വ്യക്തിത്വ പ്രഭാവം ഉന്നത കുടുംബക്കാരായ ഇസ്ലാമിക വ്യക്തികളിൽ ഉണ്ട് എന്ന ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കമ്പനി ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരുടെ നിരീക്ഷണം തീസിസ് എഴുത്തുകളിൽ ഉണ്ടോ എന്ന് വ്യക്തമല്ല. ഉണ്ടാവാൻ സാധ്യത കാണുന്നില്ല.

എന്തിനും ഏതിനും ബൃട്ടിഷ് ഭരണത്തെ അടിച്ചു തമർത്തു എന്ന രീതിയിൽ ആണ് തീസിസുകളിലെ ചരിത്ര എഴുത്തുകൾ കാണപ്പെട്ടത്.

ഇതൊന്നുമായിരുന്നില്ല വാസ്തവം. ഇന്നുള്ള ഇന്ത്യൻ അക്കാഡമിക്ക് ചരിത്രം വായിച്ചു പഠിച്ചതിന്റേയും തിരുവിതാകൂറിലും ബോംബെയിലും സൃഷ്ടിക്കപ്പെടുന്ന പൊട്ട ചരിത്ര സിനിമകൾ കണ്ടതിന്റെ സ്വാധീനവും ഈ വിധ തീസിസുകൾ എഴുതുന്ന വ്യക്തികളുടെ മാസനിക പ്രവർത്തനത്തെ ബാധിച്ചിട്ടുണ്ടാവാം എന്നു തോന്നുന്നു.

ഈ മുകളിൽ എഴുതിയ മിക്ക കാര്യങ്ങളും നേരത്തെ ഈ എഴുത്തിൽ സൂചിപ്പിച്ചിട്ടുണ്ട് എന്നാണ് തോന്നുന്നത്. പോരാത്തതിന് കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാർക്ക് ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണ പ്രസ്ഥാത്തിലെ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് അല്ലെങ്കിൽ ബൃട്ടിഷ് പൗരന്മാരായ ഉന്നത ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരുമായി നേരിട്ട് സമ്പർക്കം കിട്ടാനുള്ള യാതോരു പാതയും സമൂഹത്തിൽ നിലവിൽ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നില്ല എന്ന ഒരു വേദനാജനകമായ മാനസികാവസ്ഥയും കീഴ്തജന മാപ്പിളമാരിൽ നിലനിന്നിരുന്നു എന്നതിന്റെ സൂചനയും കണ്ടതായി ഓർക്കുന്നു.

മലബാർ ജില്ലയിൽ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് അല്ലെങ്കിൽ ബൃട്ടിഷുകാരനായ ഒരു ജില്ലാ കലക്ടർ. ഈ കലക്ടർക്ക് കീഴിൽ ഡെപ്യൂട്ടി കലക്ടറും ആ സ്ഥാനത്തിന് കീഴിൽ അനവധി താസിൽദാർമാരും. ഈ രണ്ട് സ്ഥാനങ്ങളിലും ഉള്ളത് പ്രാദേശിക വ്യക്തികൾ തന്നെ.

ഈ സ്ഥാനങ്ങളിൽ നല്ല ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭാഷാ പ്രാവീണ്യവും മറ്റ് വ്യക്തി പ്രഭാവങ്ങളും ഉള്ള ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരെ (Tellicherryയിൽ നിന്നുമുള്ള തീയരെ വരെ) ഒരു പൊതുപരിക്ഷയുടെ അടിസ്ഥാനത്തിൽ തിരഞ്ഞെടുത്ത് നിയമിക്കാൻ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കമ്പനിക്ക് പതിറ്റാണ്ടുകൾ തന്നെ കാത്തിരിക്കേണ്ടി വന്നിരുന്നു.

ഈ വിധമായുള്ള ഒരു Madras Presidency Public Service Commission ഉന്നത ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരെ നിയമിച്ചുതുടങ്ങുന്നതുവരെ മലബാറിലെ എല്ലാ ഇടത്തും ഭരണം നടത്തിയിരുന്നത് പ്രാദേശിക പാരമ്പര്യ അധികാരി കുടുംബക്കാർ തന്നെയാണ്.

ഈ കൂട്ടർ തനി കള്ളന്മാരും പിന്നിൽനിന്നും കുത്തുന്നവരും അഴിമതിക്കാരും യാതോരു വകതിരിവില്ലാത്തവരും ആയിരുന്നു എന്ന വാസ്തവം മലബാർ മാന്വലിൽ രേഖപ്പെടുത്തിക്കാണുന്നുണ്ട്.

ഇവർക്ക് ഇടയിൽ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണം നിമയ ചട്ടങ്ങളും അവ നടപ്പിലാക്കാനുള്ള കോടതികളും സ്ഥാപിച്ചെടുത്തു. ഇവയിൽ ജഡ്ജ് മാരായി പ്രവർത്തിച്ചിരുന്നത് ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷുകാരോ അതുമല്ലെങ്കിൽ മറ്റ് ബൃട്ടിഷുകാരോ ആയിരുന്നു എന്നാണ് തോന്നുന്നത്.

ഭൂസ്വത്ത് ഭൂജന്മിയുടെ കൈകളിൽ തന്നെയാണ് ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നത്. ഈ വിധം തന്നെയാണ് അന്നും ഇന്നും ഇങ്ഗ്ളണ്ടിൽ ഉള്ളത്. അതുകൊണ്ട് അവിടെ യാതോരു പ്രശ്നവും കണ്ടിരുന്നില്ല.

എന്നാൽ ബൃട്ടിണിൽ തന്നെയുള്ള Irelandൽ ഈ വിധമായുള്ള ഒരു സാമൂഹിക അന്തരീക്ഷം പ്രശ്നം തന്നെയായിരുന്നു. അവിടെ ജന്മികൾ കൃഷിഭൂമി പാട്ടമായി നൽകുമെങ്കിലും, ആ ഭൂമി പാട്ടക്കാരനിൽ നിന്നും ഭൂജ്മി ഭൂമി തട്ടിയെടുക്കുന്ന ഒരു പതിവുണ്ടായിരുന്നു. ആ ഭൂജന്മികളെ land grabbers എന്നുവരെ നിർവ്വചിക്കപ്പെട്ടിരുന്നു. ഈ ദുരവസ്ഥയ്ക്കും ഐറിഷുകാർ ഇങ്ഗ്ളണ്ടിനെയാണ് അന്ന് പഴിച്ചിരുന്നത്. ഇന്നും ആരോപണത്തിൽ വ്യത്യാസം വന്നിട്ടില്ല.

എന്നാൽ സാമൂഹിക പിശക് മറ്റൊന്നായിരുന്നു. ഭൂജന്മകളുടെ സാന്നിദ്ധ്യം അല്ല പ്രശ്നം എന്ന് മനസ്സിലാക്കേണ്ടിയിരിക്കുന്നു.

ഇത്രയും കാര്യം എഴുതിയത് ഈ എഴുത്ത് വീണ്ടും എഴുതിത്തുടങ്ങാനുള്ള ഒരു warming up എന്ന രീതിയിൽ ആണ്. അടുത്ത എഴുത്തിൽ കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാർ മാത്രമല്ല, മറിച്ച് മറ്റ് കീഴ്ജനങ്ങളും മറ്റും നേരിട്ട ഒരു പ്രത്യേക സാമൂഹിക തടസ്സത്തെക്കുറിച്ച് പ്രതിപാദിക്കാം.

എഴുതിക്കൊണ്ടിരുന്ന വിഷയം ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിൽ നടമാടിയ മാപ്പിള ലഹളയെന്ന് വിശേഷിപ്പിക്കപ്പെടുന്ന ചരിത്ര സംഭവം ആയിരുന്നു. അന്ന് എഴുതുന്ന അവസരത്തിൽ കാര്യങ്ങൾ മനസ്സിൽ ഒരു അരുവി കണക്കെ ഒഴുകി വന്നിരുന്നു. എന്നാൽ ഇന്ന് ഇപ്പോൾ മനസ്സിൽ നോക്കുമ്പോൾ ആ അരുവിയുടെ യാതോരു അംശവും കാണുന്നില്ല.

അന്ന് എന്തൊക്കെയാണ് എഴുതാനിരുന്നത് എന്നതുതന്നെ വിസ്മൃയിൽ മാഞ്ഞുപോയിരിക്കുന്നു.

എന്നാലും എഴുത്തിന്റെ ഒഴുക്കിലേക്ക് പിടിച്ചുകയറാൻ ശ്രമിക്കുകയാണ്.

മാപ്പിള ലഹളയെക്കുറിച്ച് പ്രാദേശിക ഇസ്ലാമിക പണ്ഡിതർ ഏതുവിധത്തിലാണ് മനസ്സിലാക്കിയത് എന്ന് ഈ എഴുത്തുകാരന് അറിയില്ല. എന്നിരുന്നാലും ഡോക്ട്രൽ തീസുസുകളായി സമർപ്പിക്കപ്പെട്ട ചില എഴുത്തുകൾ ഇപ്പോൾ കൺമുൻപിൽ ഉണ്ട്.

ഈ വിധ എഴുത്തുകൾക്ക് ഒരു വൻ പാളിച്ചയായി കാണപ്പെടുന്ന കാര്യങ്ങളിൽ ഒന്ന് ഇസ്ലാമിന്റേയോ അതുമല്ലെങ്കിൽ മുഹമ്മദിന്റേയോ ഏറ്റവും ഉജ്ജ്വല ആശയമായ സാമൂഹികമായും വ്യക്തിത്വപരമായും വ്യക്തികൾക്ക് ഒരു പരന്ന രീതിയിലുള്ളതും ഉന്നതനിലവാരത്തിലുള്ളതുമായ വ്യക്തിത്വവും അന്തസും എന്ന കാഴ്ചപ്പാടിനെ തീസിസ് പണ്ഡിതർക്ക് കാണാൻ പറ്റിയിട്ടില്ലാ എന്നതാണ് എന്നു തോന്നുന്നു.

മറ്റൊന്ന് പ്രാദേശിക സാമൂഹിക അന്തരീക്ഷത്തിലെ ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷ എന്ന രാക്ഷസീയ വസ്തുവിന്റെ അസ്തിത്വത്തെക്കുറിച്ച് യാതോരു അവബോധവും ഇല്ലാ എന്നുള്ളതാണ്.

പോരാത്തതിന്, മലബാറുകളിലും ദക്ഷിണേഷ്യയിൽ മുഴുവനായും ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണം എന്ന അതിഗംഭീര ചരിത്ര സംവഭത്തെ ഒരു ഉന്നത നിലവാരത്തിൽ നിന്നുകൊണ്ട് മനസ്സിലാക്കാനോ സമീപിക്കാനോ ആയില്ല എന്നുള്ളതും ഒരു പൊതുവായുള്ള പോരായ്മയായി നിലനിൽക്കുന്നുണ്ട്.

സാമൂഹികമായി എന്തിന്റെയൊക്കെയോ അടിയിൽ നിന്നുകൊണ്ടാണ് ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണത്തെ വിലയിരുത്താൻ പലരും ഒരുമ്പിടുന്നത്.

തീസുസുകൾ എഴുതുന്ന പണ്ഡിതർക്ക് ഇന്നുള്ള ഇന്ത്യ അന്നില്ലായിരുന്നുവെന്നോ, ഇന്ന് കാണുന്ന കേരളം അന്നില്ലായിരുന്നുവെന്നോ അറിവ് ലഭിക്കാത്ത ഒരു ഭാവവും കാണുന്നുണ്ട്. ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിലും ഉത്തര മലബാറിലും മൊത്തമായി 29 ഓളം വളരെ ചെറിയ രാജ്യങ്ങളോ അതുപോലുള്ള പ്രദേശങ്ങളോ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു. ഇവയെ എല്ലാം ചേർത്തെടുത്ത് മെഡ്രാസ് പ്രസിഡൻയിലെ ഒരു ഒറ്റ ജില്ലയാക്കുകയും അതിന് ശേഷം, അവിടങ്ങളിൽ ജനാധിപത്യമെന്ന ഭരണ സംവിധാനം നടപ്പാക്കിയതും ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണം ആണ്.

ഈ വിധമായുള്ള ഒരു അതി നൂതനമായി ചരിത്ര സംഭവം നടന്നപ്പോൾ, അവിടെ ജീവിച്ചിരുന്ന എല്ലാ ജന വംശങ്ങളിലും പലവിധ ഏറ്റക്കുറിച്ചലുകളും പൊളിച്ചെഴുത്തുകളും മറ്റും സംഭവിച്ചിരുന്നു. പല പാരമ്പര്യ ഉന്നത ജനക്കൂട്ടങ്ങളിൽ വൻ വെപ്രാളം തന്നെ സംഭവിച്ചിരുന്നു.

ഈ വെപ്രാളം ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷുകാർ അവരുടെ വീടുകളിൽ കയറും എന്നും അവരുടെ സമ്പത്തും സ്ത്രീജനങ്ങളേയും കൈവശപ്പെടുത്തും എന്നതായിരുന്നില്ല. മറിച്ച്, പാരമ്പര്യമായി അവരേക്കാൾ കീഴിൽ നിലനിന്നിരുന്ന ജനക്കൂട്ടങ്ങൾ സാമൂഹികമായി വളരും എന്നും അവർ തങ്ങളുടെ സാമൂഹിക സ്ഥാനങ്ങളും സ്വത്തുക്കളും കൈവശപ്പെടുത്തുമെന്നും തങ്ങളെ വാക്കുകളിലെ മഹത് സ്ഥാനങ്ങളിൽനിന്നും അവർ കുടിയിറക്കും എന്ന വെപ്രാളം തന്നെയായിരുന്നു.

ഇവിടേയും മനസ്സിലാക്കേണ്ടത്, പല കീഴ്ജനങ്ങളും ഇസ്ലാമിലേക്ക് കയറയിരുന്നു എന്നത് ശരിയാണ് എങ്കിൽ കൂടി, പാരമ്പര്യമായി സാമൂഹിക മഹിമയിൽ ജീവിച്ചിരുന്ന ഇസ്ലാമിക കുടുംബങ്ങളും മലബാറുകളിൽ അന്ന് ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു.

H.V. Connolly എന്ന ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷുകാരനായ മലബാർ ജീല്ലാ കലക്ടർ യഥാർത്ഥത്തിൽ മാപ്പിളമാരോട് പൊതുവായും കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാരോടു പ്രത്യേകമായും അനുകമ്പയുള്ള വ്യക്തിയാണ് എന്ന ഒരു ആരോപണം തന്നെ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണം മാപ്പിള സങ്കർഷങ്ങളെക്കുറിച്ച് പഠിക്കാൻ നിയോഗിച്ച Mr. Strange എന്ന ന്യായാധിപൻ പുറപ്പെടുവിച്ചിരുന്നു.

എന്നാൽ H.V. Connollyയെ ഏതാനും തെമ്മാടി വ്യക്തികൾ വെട്ടികൊലപ്പെടുത്തിയത് ഇസ്ലാമിക പ്രവർത്തനമായുള്ള ഒരു വൻ അഹ്ളാദകരമായ സംഭവം എന്ന രീതിയിൽ ആണ് തീസിസുകാർ എഴുതിക്കാണുന്നത്. ഈ വിധ വിഡ്ഢി പ്രവർത്തനത്തവുമായി ചെറിയ തോതിലെങ്കിലും മൗലിക ഇസ്ലാമിനെക്കുറിച്ച് വകതിരിവള്ള വ്യക്തികൾ ഇസ്ലാമിനെകൂട്ടിക്കലർത്താൻ ശ്രമിക്കും എന്ന് തോന്നുന്നില്ല.

ദക്ഷിണേഷ്യയിൽ അന്യാദൃശ്യമായ വ്യക്തിത്വ പ്രഭാവം ഉന്നത കുടുംബക്കാരായ ഇസ്ലാമിക വ്യക്തികളിൽ ഉണ്ട് എന്ന ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കമ്പനി ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരുടെ നിരീക്ഷണം തീസിസ് എഴുത്തുകളിൽ ഉണ്ടോ എന്ന് വ്യക്തമല്ല. ഉണ്ടാവാൻ സാധ്യത കാണുന്നില്ല.

എന്തിനും ഏതിനും ബൃട്ടിഷ് ഭരണത്തെ അടിച്ചു തമർത്തു എന്ന രീതിയിൽ ആണ് തീസിസുകളിലെ ചരിത്ര എഴുത്തുകൾ കാണപ്പെട്ടത്.

ഇതൊന്നുമായിരുന്നില്ല വാസ്തവം. ഇന്നുള്ള ഇന്ത്യൻ അക്കാഡമിക്ക് ചരിത്രം വായിച്ചു പഠിച്ചതിന്റേയും തിരുവിതാകൂറിലും ബോംബെയിലും സൃഷ്ടിക്കപ്പെടുന്ന പൊട്ട ചരിത്ര സിനിമകൾ കണ്ടതിന്റെ സ്വാധീനവും ഈ വിധ തീസിസുകൾ എഴുതുന്ന വ്യക്തികളുടെ മാസനിക പ്രവർത്തനത്തെ ബാധിച്ചിട്ടുണ്ടാവാം എന്നു തോന്നുന്നു.

ഈ മുകളിൽ എഴുതിയ മിക്ക കാര്യങ്ങളും നേരത്തെ ഈ എഴുത്തിൽ സൂചിപ്പിച്ചിട്ടുണ്ട് എന്നാണ് തോന്നുന്നത്. പോരാത്തതിന് കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാർക്ക് ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണ പ്രസ്ഥാത്തിലെ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് അല്ലെങ്കിൽ ബൃട്ടിഷ് പൗരന്മാരായ ഉന്നത ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരുമായി നേരിട്ട് സമ്പർക്കം കിട്ടാനുള്ള യാതോരു പാതയും സമൂഹത്തിൽ നിലവിൽ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നില്ല എന്ന ഒരു വേദനാജനകമായ മാനസികാവസ്ഥയും കീഴ്തജന മാപ്പിളമാരിൽ നിലനിന്നിരുന്നു എന്നതിന്റെ സൂചനയും കണ്ടതായി ഓർക്കുന്നു.

മലബാർ ജില്ലയിൽ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് അല്ലെങ്കിൽ ബൃട്ടിഷുകാരനായ ഒരു ജില്ലാ കലക്ടർ. ഈ കലക്ടർക്ക് കീഴിൽ ഡെപ്യൂട്ടി കലക്ടറും ആ സ്ഥാനത്തിന് കീഴിൽ അനവധി താസിൽദാർമാരും. ഈ രണ്ട് സ്ഥാനങ്ങളിലും ഉള്ളത് പ്രാദേശിക വ്യക്തികൾ തന്നെ.

ഈ സ്ഥാനങ്ങളിൽ നല്ല ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭാഷാ പ്രാവീണ്യവും മറ്റ് വ്യക്തി പ്രഭാവങ്ങളും ഉള്ള ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരെ (Tellicherryയിൽ നിന്നുമുള്ള തീയരെ വരെ) ഒരു പൊതുപരിക്ഷയുടെ അടിസ്ഥാനത്തിൽ തിരഞ്ഞെടുത്ത് നിയമിക്കാൻ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കമ്പനിക്ക് പതിറ്റാണ്ടുകൾ തന്നെ കാത്തിരിക്കേണ്ടി വന്നിരുന്നു.

ഈ വിധമായുള്ള ഒരു Madras Presidency Public Service Commission ഉന്നത ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥരെ നിയമിച്ചുതുടങ്ങുന്നതുവരെ മലബാറിലെ എല്ലാ ഇടത്തും ഭരണം നടത്തിയിരുന്നത് പ്രാദേശിക പാരമ്പര്യ അധികാരി കുടുംബക്കാർ തന്നെയാണ്.

ഈ കൂട്ടർ തനി കള്ളന്മാരും പിന്നിൽനിന്നും കുത്തുന്നവരും അഴിമതിക്കാരും യാതോരു വകതിരിവില്ലാത്തവരും ആയിരുന്നു എന്ന വാസ്തവം മലബാർ മാന്വലിൽ രേഖപ്പെടുത്തിക്കാണുന്നുണ്ട്.

ഇവർക്ക് ഇടയിൽ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണം നിമയ ചട്ടങ്ങളും അവ നടപ്പിലാക്കാനുള്ള കോടതികളും സ്ഥാപിച്ചെടുത്തു. ഇവയിൽ ജഡ്ജ് മാരായി പ്രവർത്തിച്ചിരുന്നത് ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷുകാരോ അതുമല്ലെങ്കിൽ മറ്റ് ബൃട്ടിഷുകാരോ ആയിരുന്നു എന്നാണ് തോന്നുന്നത്.

ഭൂസ്വത്ത് ഭൂജന്മിയുടെ കൈകളിൽ തന്നെയാണ് ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നത്. ഈ വിധം തന്നെയാണ് അന്നും ഇന്നും ഇങ്ഗ്ളണ്ടിൽ ഉള്ളത്. അതുകൊണ്ട് അവിടെ യാതോരു പ്രശ്നവും കണ്ടിരുന്നില്ല.

എന്നാൽ ബൃട്ടിണിൽ തന്നെയുള്ള Irelandൽ ഈ വിധമായുള്ള ഒരു സാമൂഹിക അന്തരീക്ഷം പ്രശ്നം തന്നെയായിരുന്നു. അവിടെ ജന്മികൾ കൃഷിഭൂമി പാട്ടമായി നൽകുമെങ്കിലും, ആ ഭൂമി പാട്ടക്കാരനിൽ നിന്നും ഭൂജ്മി ഭൂമി തട്ടിയെടുക്കുന്ന ഒരു പതിവുണ്ടായിരുന്നു. ആ ഭൂജന്മികളെ land grabbers എന്നുവരെ നിർവ്വചിക്കപ്പെട്ടിരുന്നു. ഈ ദുരവസ്ഥയ്ക്കും ഐറിഷുകാർ ഇങ്ഗ്ളണ്ടിനെയാണ് അന്ന് പഴിച്ചിരുന്നത്. ഇന്നും ആരോപണത്തിൽ വ്യത്യാസം വന്നിട്ടില്ല.

എന്നാൽ സാമൂഹിക പിശക് മറ്റൊന്നായിരുന്നു. ഭൂജന്മകളുടെ സാന്നിദ്ധ്യം അല്ല പ്രശ്നം എന്ന് മനസ്സിലാക്കേണ്ടിയിരിക്കുന്നു.

ഇത്രയും കാര്യം എഴുതിയത് ഈ എഴുത്ത് വീണ്ടും എഴുതിത്തുടങ്ങാനുള്ള ഒരു warming up എന്ന രീതിയിൽ ആണ്. അടുത്ത എഴുത്തിൽ കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാർ മാത്രമല്ല, മറിച്ച് മറ്റ് കീഴ്ജനങ്ങളും മറ്റും നേരിട്ട ഒരു പ്രത്യേക സാമൂഹിക തടസ്സത്തെക്കുറിച്ച് പ്രതിപാദിക്കാം.

Last edited by VED on Sun Jun 15, 2025 11:37 am, edited 1 time in total.

4. ഹിന്ദുക്കളും ഇസ്ലാം മതവിശ്വാസികളും അന്ന്

ഏതാണ്ട് 1836കൾ മുതൽ ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിൽ മാപ്പിളമാരിൽ ചില കൂട്ടരും ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷത്തിൽ പെട്ട ചിലരും തമ്മിൽ നിരന്തരമായ ഏറ്റുമുട്ടൽ ഭാവം നിലനിന്നിരുന്നു എന്നു കാണുന്നുണ്ട്.

ഈ കാര്യത്തെക്കുറിച്ച് കൂടുതൽ കാര്യങ്ങൾ പറയുന്നതിന് മുൻപായി രണ്ടു പക്ഷത്തുള്ള ജനക്കൂട്ടങ്ങളേയും വ്യക്തമായി നിർവ്വചിക്കേണ്ടതുണ്ട്. അല്ലെങ്കിൽ ഹിന്ദു, മുസ്ലിം എന്നീ പദങ്ങൾ കൊണ്ട് ഇന്ന് നിർവ്വചിക്കപ്പെടുന്ന വ്യക്തികളുമായി ഈ വിധ പദ പ്രയോഗങ്ങൾ കുഴഞ്ഞുപോയേക്കാം.

ഹിന്ദുക്കൾ എന്ന് പറയുന്ന മതക്കാർ ബ്രാഹ്മണരാണ്.

അവരുടെ പക്ഷത്ത് അന്ന് ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നത് അമ്പലവാസികളും നായർമാരും ആണ്. അവർക്ക് കീഴിൽ വരുന്ന ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിലെ മക്കത്തായ തീയരും അവർക്കും കീഴിൽ വരുന്ന അനവധി കീഴ്ജനങ്ങളും ബ്രാഹ്മണ (ഹൈന്ദവ) പക്ഷക്കാരുടെ ആശ്രിതർ മാത്രമാണ്. ചെറുമർ, പോലുള്ളവർ യഥാർത്ഥത്തിൽ പൂർണ്ണമായും അടിമകളും അർദ്ധ മനുഷ്യരും തന്നെ, അന്ന്.

വ്യക്തമായും മനസ്സിലാക്കേണ്ടത് ഇന്ന് മലബാർ പ്രദേശത്ത് ഹൈന്ദവ മേൽവിലാസം പാറിക്കാണിക്കുന്നവരിൽ ഒരു വൻ ശതമാനം പേരും വടക്കേ മലബാറിലെ മരുമക്കത്തായ തീയരും ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിലെ മക്കത്തായ തീയരും ആണ്. എന്നാൽ ഈ രണ്ട് കൂട്ടരോടും ആയിരുന്നില്ല, അന്ന് 1830കളിൽ മാപ്പിളമാർ ഏറ്റുമുട്ടിക്കൊണ്ടിരുന്നത്.

പൊതുവായി പറഞ്ഞാൽ, ബ്രാഹ്മണർ സസ്യബുക്കുകളും ആയുധ പ്രയോഗങ്ങളിൽ നിന്നും വിട്ടു നിൽക്കുന്നവരും ആയിരിക്കാം. എന്നാൽ അവർ സാമൂഹികമായി പ്രാദേശിക ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷയുടെ മുകളിൽ നിന്നു കൊണ്ട് മറ്റ് ജനവംശങ്ങളെ അടിച്ചമർത്തിയവർ തന്നെ. അവരുടെ കാലാൾപടയായി നിന്നിരുന്നത് നായർ മേലാളന്മാരാണ്.

ബ്രാഹ്മണ ഹൈന്ദവതയിൽ കീഴ്ജനങ്ങൾ കയറി നിറഞ്ഞ ഈ കാലത്ത്, ഹൈന്ദവ മതം ഈ പുതിയ ഹൈന്ദവരുടെ മുഖഭാവമാണ് പ്രകടിപ്പിക്കുക.

ഇനി അന്നത്തെ മാപ്പിളമാരുടെ കാര്യം.

ഉത്തര മലബാറിലും ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിലും ഇസ്ലാം മതവിശ്വാസികൾ ഏതാനും നൂറ്റാണ്ടുകൾക്ക് മുൻപേ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു. അവരിൽ ഒരു വിഭാഗക്കാർ ഉന്നത കുടുംബക്കാർ തന്നെയായിരുന്നു. അറബി രക്തപാതയിൽ ഉറച്ചു നിന്നിരുന്ന പല ഇസ്ലാമിക കുടുംബക്കാരും വൻ വര്യേണ്യരായി നിലനിന്നിരുന്നു.

പോരാത്തതിന്, മൈസൂറുകാരുടെ ആക്രമണ സമയത്ത് ബ്രാഹ്മണ, അമ്പലവാസി, നായർ കുടുംബക്കാർ പലതും ഇസ്ലാമിലേക്ക് ചേർന്നിരുന്നു. അവരിൽ പലരും അവരുടെ വരേണ്യഭാവം തുടർന്നും നിലനിർത്തിയവർ തന്നെ.

ഇവർക്കും ഉപരിയായി, Cannanore പ്രദേശത്ത് യവന രക്തപാതയിൽ ഉള്ള ഇസ്ലാമിക കുടുബക്കാരും ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു എന്നും തോന്നുന്നു. ഇവർ മിക്കവാറും അവരുടെ രക്തബന്ധ പാത വളരെ ശുദ്ധമായി നിലനിർത്തിരുന്നു എന്ന് തോന്നുന്നു.

ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിൽ ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷത്തിനെ വൻ നീരസത്തോടുകൂടി വിക്ഷിച്ചിരുന്നത് യഥാർത്ഥത്തിൽ ഇവരാരും തന്നെയായിരുന്നില്ല. പോരാത്തതിന്, കുണ്ടോട്ടിയിലെ തങ്ങൾ കുടുംബക്കാരും അവരുടെ പക്ഷക്കാരും വ്യത്യസ്തരായി നിലനിന്നിരുന്നു എന്നും തോന്നുന്നു.

ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിൽ ഇസ്ലാമിക മതത്തിന് ഒരു ഭീകരഭാവം ഉണ്ട് എന്ന് ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷക്കാർക്ക് തിരിച്ചറിവ് വന്നത് കീഴ്ഡന വംശങ്ങൾ കൂട്ടത്തോടെ ഇല്ലാമിലേക്ക് കയറിത്തുടങ്ങിയതോടുകൂടിയാണ്.

ഈ ഭീകര ഭാവം ഇസ്ലാം മതത്തിന്റേയും ആ ആദ്ധ്യാത്മികതയുടെ ആചാര്യ സ്ഥാനത്തുനിൽക്കുന്നുവെന്ന് മനസ്സിലാക്കപ്പെടുന്ന മുഹമ്മദിന്റേയും നൈസർഗ്ഗികമായുള്ള ഒരു മാസനിക സിദ്ധാന്തം ആണ് എന്നാണ് പൊതുവായി അന്നുള്ളതും ഇന്നുള്ളതുമായ ഹൈന്ദവ പക്ഷം ചത്രീകരികരിക്കുന്നത്.

എന്നാൽ ഈ കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാരിലെ വ്യക്തിപരമായുള്ളതും സാമൂഹികമായുള്ളതുമായ പക അവരുടെ സാമൂഹിക അവസ്ഥയുടെ ഒരു പ്രതിഫലനം മാത്രമാകാം.

കാരണം, ഈ ഒരു സാമൂഹിക ഏറ്റുമുട്ടൽ തുടങ്ങുന്നതുവരെ ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷക്കാരും ഇസ്ലാമിലെ ഉന്നത കുടുംബക്കാരും അറബി കച്ചവട സംഘങ്ങളും മറ്റും ഒത്തൊരുമായോടുകൂടിതന്നെയാണ് ജീവിച്ചത്. അവരിലെ പൊതുവായുള്ള ലക്ഷ്യം കീഴ്ജന വ്യക്തികളെ അവർ തളച്ചിടപ്പെട്ട സാമൂഹിക അവസ്ഥയിൽ നിന്നും ഉയരാൻ സമ്മതിക്കരുത് എന്നതുതന്നെയാവാം.

വ്യക്തികൾക്ക് അവർ ജനിച്ചനാൾ മുതൽ സമൂഹത്തിൽ നേരിട്ടു കാണുന്നതും കേൾക്കുന്നതും മറ്റുമായ കാര്യങ്ങൾക്ക് അപ്പുറം അറിവ് ലഭക്കാൻ സാധ്യത കുറവാണ്.

ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിൽ ബ്രാഹ്രണ കുടുംബക്കാരായ ഭൂജന്മികൾ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു. അവരുടെ മേൽനോട്ടക്കാരായ നായർമാർ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു. ഭൂജന്മികൾ നായർമാർക്കും ചിലപ്പോൾ മക്കത്തായ തീയർ വ്യക്തികൾക്കും ഭൂമി പാട്ടത്തിന് നൽകുന്നു. ഈ പാട്ടക്കാർ അവരുടെ കൃഷിയിടത്തിൽ വേലചെയ്യാനായി അടിമവ്യക്തികളെ വിലക്കെടുക്കുകയോ പാട്ടത്തിന് എടുക്കുകയോ ചെയ്യുന്നു.

ഈ അടിമ വ്യക്തികളിൽ വിള്പവ ഭാവം ഇല്ല. അവരിൽ ഉള്ളത് യജമാന ഭക്തിയാണ്.

ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണകാലത്ത് കീഴ്ഡന വ്യക്തികളിൽ പലരും ഇസ്ലാമിലേക്ക് കയറി. അവർ ഭൂമി പാട്ടത്തിന് എടുത്തു തടുങ്ങി. അവരിൽ പലരും കച്ചവടം നടത്തിത്തുടങ്ങി. കാളവണ്ടികളുടേയും ചരക്കുതോണികളുടേയും ഉടമസ്ഥരായി.

ഇവരിൽ വ്യക്തിത്വ പരമായും മാനസികമായും വൻ മുന്നോറ്റം സംഭവിക്കുന്നു.

ഇത് ഏറ്റവും പ്രശ്നമാവുന്നത് നായർ മേലാളന്മാക്കാണ്. കാരണം, പ്രാദേശിക ഭാഷാകോഡുകൾക്ക് ഈ വിധമായുള്ള ഒരു പരിവർത്തനത്തെ ഉൾക്കൊള്ളാൻ ആവില്ല. തിരുവന്തപുരത്തെ ഓട്ടോ ഡ്രൈവർ പോലീസ് ശിപായിയെ നീ എന്ന് സമ്പോധന ചെയ്യുന്നതുപോലുള്ള ഒരു ഭാഷാ കോഡിങ്ങ് പ്രശ്നം ഉയർന്നുവരും.

നായർമാർക്ക് കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിള വ്യക്തിയെ അവരുടെ അടിമ വ്യക്തിയായിത്തന്നെ കാണാനാണ് ആഗ്രഹം നിലനിൽക്കുക. നായർമാർ അവരുടെ അടിമകളെ പാരമ്പര്യമായി വെട്ടി നുറുക്കി നിയന്ത്രിച്ചവർ തന്നെയാണ്. അങ്ങിനെ ചെയ്യുമ്പോൾ, ആ അടിമ ജനത്തിന് അവരോട് വൻ ആദരവാണ് വളരുക. ഇന്നത്തെ ജനത്തിന് പോലീസുകരോടുള്ള ഭാവം തന്നെ.

ഈ നായർമാർ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണത്തിന്റെ ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥർ ആയാൽ, അവരെ കൃത്യമായി നിയന്ത്രിക്കാൻ ഏകനായ ജില്ലാ കലക്ടർക്ക് ആവില്ല. കാരണം, ഭരണത്തിൽ എല്ലാരും ഈ പ്രദേശത്തുള്ളവർ തന്നെ. അവരുടെ മാനസികവും സാമൂഹികവും ആയ ഭാവങ്ങളും ചിന്തകളും ഗൂഡാലോചനകളും ഭരണയന്ത്രത്തിൽ ഒരു പാടമാതിരി പടർന്നുകിടക്കും.

രണ്ടു പക്ഷത്തുള്ള വ്യക്തികളേയും കുറ്റം പറയാൻ ആവില്ല. അവരിൽ എല്ലാവർക്കും പല തരം വേവലാതികൾ ഉണ്ട്. ഈ വേവലാതികൾ സൃഷ്ടിക്കുന്ന പ്രാദേശിക കാട്ടള ഭാഷ അദൃശ്യമായി നിന്നുകൊണ്ട് വൻ സൗന്ദര്യമുള്ള പാട്ടുകളും ആഘോഷതിമിർപ്പുകളും നടത്തിപ്പുചെയ്യുന്നു.

സാമൂഹിക നേതൃത്വം എന്നത് അത്യന്താപേക്ഷിതമായ ഒരു വ്യക്തിത്വ ഘടകം ആണ് എന്ന് വരേണ്യവ്യക്തികൾക്ക് ഈ ഭാഷ നിത്യവും അറിവും താക്കീതും നൽകുന്നു. അവരുടെ സാമൂഹിക ഉന്നതങ്ങളിൽ പടവെട്ടി നിൽക്കണമെന്ന് മനസ്സിൽ നിശബ്ദമായി മന്ത്രിച്ചു കൊടുക്കുന്നു.

കുറ്റം മുഴുവൻ ആങ്ങ് അകലെ ഉന്നതങ്ങളിൽ നിന്നുകൊണ്ട് സാമൂഹിക പരിവർത്തനത്തിനായി പദ്ധതിയിടുന്ന ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണത്തിന് മേൽ ചാർത്തുക എന്നത് ഒരു വളരെ പ്രായോഗികമായ കാര്യമാണ്. കാരണം, ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് പക്ഷത്തിനെ ജനങ്ങൾക്ക് പറഞ്ഞു മനസ്സിലാക്കിക്കൊടുക്കാൻ പ്രാപ്തരായവരോ താൽപ്പര്യമുള്ളവരോ സമൂഹത്തിൽ ഉണ്ടായിരിന്നിരിക്കില്ല.

ഈ മുകളിൽ എഴുതിയ മിക്ക കാര്യങ്ങളും നേരത്തെ ഈ എഴുത്തിൽ എഴുതിയിട്ടുണ്ട് എന്നാണ് തോന്നുന്നത്.

ഇന്ത്യൻ ഔപചാരിക ചരിത്രകാരന്മാരും തീസിസ് എഴുത്തുകാരും ഇവയിൽ പലതിനും അർഹമായ പരിഗണനൽകാതെ, 1830കളിൽ മാപ്പിള വ്യക്തികൾ നടത്തിയ ആക്രമങ്ങളെ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണത്തിന് എതിരായുള്ള ഒരു സ്വാതന്ത്ര്യ സമര പോരാട്ടമായി വിവരിച്ചുകൊണ്ട് വായനക്കാരേയും ചരിത്രം പഠിക്കാൻ വരുന്നവരേയും വിഡ്ഢികൾ ആക്കുന്ന ഒരു പരിപാടി കാണുന്നുണ്ട് എന്നാണ് തോന്നുന്നത്.

ഈ കാര്യത്തെക്കുറിച്ച് കൂടുതൽ കാര്യങ്ങൾ പറയുന്നതിന് മുൻപായി രണ്ടു പക്ഷത്തുള്ള ജനക്കൂട്ടങ്ങളേയും വ്യക്തമായി നിർവ്വചിക്കേണ്ടതുണ്ട്. അല്ലെങ്കിൽ ഹിന്ദു, മുസ്ലിം എന്നീ പദങ്ങൾ കൊണ്ട് ഇന്ന് നിർവ്വചിക്കപ്പെടുന്ന വ്യക്തികളുമായി ഈ വിധ പദ പ്രയോഗങ്ങൾ കുഴഞ്ഞുപോയേക്കാം.

ഹിന്ദുക്കൾ എന്ന് പറയുന്ന മതക്കാർ ബ്രാഹ്മണരാണ്.

അവരുടെ പക്ഷത്ത് അന്ന് ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നത് അമ്പലവാസികളും നായർമാരും ആണ്. അവർക്ക് കീഴിൽ വരുന്ന ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിലെ മക്കത്തായ തീയരും അവർക്കും കീഴിൽ വരുന്ന അനവധി കീഴ്ജനങ്ങളും ബ്രാഹ്മണ (ഹൈന്ദവ) പക്ഷക്കാരുടെ ആശ്രിതർ മാത്രമാണ്. ചെറുമർ, പോലുള്ളവർ യഥാർത്ഥത്തിൽ പൂർണ്ണമായും അടിമകളും അർദ്ധ മനുഷ്യരും തന്നെ, അന്ന്.

വ്യക്തമായും മനസ്സിലാക്കേണ്ടത് ഇന്ന് മലബാർ പ്രദേശത്ത് ഹൈന്ദവ മേൽവിലാസം പാറിക്കാണിക്കുന്നവരിൽ ഒരു വൻ ശതമാനം പേരും വടക്കേ മലബാറിലെ മരുമക്കത്തായ തീയരും ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിലെ മക്കത്തായ തീയരും ആണ്. എന്നാൽ ഈ രണ്ട് കൂട്ടരോടും ആയിരുന്നില്ല, അന്ന് 1830കളിൽ മാപ്പിളമാർ ഏറ്റുമുട്ടിക്കൊണ്ടിരുന്നത്.

പൊതുവായി പറഞ്ഞാൽ, ബ്രാഹ്മണർ സസ്യബുക്കുകളും ആയുധ പ്രയോഗങ്ങളിൽ നിന്നും വിട്ടു നിൽക്കുന്നവരും ആയിരിക്കാം. എന്നാൽ അവർ സാമൂഹികമായി പ്രാദേശിക ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷയുടെ മുകളിൽ നിന്നു കൊണ്ട് മറ്റ് ജനവംശങ്ങളെ അടിച്ചമർത്തിയവർ തന്നെ. അവരുടെ കാലാൾപടയായി നിന്നിരുന്നത് നായർ മേലാളന്മാരാണ്.

ബ്രാഹ്മണ ഹൈന്ദവതയിൽ കീഴ്ജനങ്ങൾ കയറി നിറഞ്ഞ ഈ കാലത്ത്, ഹൈന്ദവ മതം ഈ പുതിയ ഹൈന്ദവരുടെ മുഖഭാവമാണ് പ്രകടിപ്പിക്കുക.

ഇനി അന്നത്തെ മാപ്പിളമാരുടെ കാര്യം.

ഉത്തര മലബാറിലും ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിലും ഇസ്ലാം മതവിശ്വാസികൾ ഏതാനും നൂറ്റാണ്ടുകൾക്ക് മുൻപേ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു. അവരിൽ ഒരു വിഭാഗക്കാർ ഉന്നത കുടുംബക്കാർ തന്നെയായിരുന്നു. അറബി രക്തപാതയിൽ ഉറച്ചു നിന്നിരുന്ന പല ഇസ്ലാമിക കുടുംബക്കാരും വൻ വര്യേണ്യരായി നിലനിന്നിരുന്നു.

പോരാത്തതിന്, മൈസൂറുകാരുടെ ആക്രമണ സമയത്ത് ബ്രാഹ്മണ, അമ്പലവാസി, നായർ കുടുംബക്കാർ പലതും ഇസ്ലാമിലേക്ക് ചേർന്നിരുന്നു. അവരിൽ പലരും അവരുടെ വരേണ്യഭാവം തുടർന്നും നിലനിർത്തിയവർ തന്നെ.

ഇവർക്കും ഉപരിയായി, Cannanore പ്രദേശത്ത് യവന രക്തപാതയിൽ ഉള്ള ഇസ്ലാമിക കുടുബക്കാരും ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു എന്നും തോന്നുന്നു. ഇവർ മിക്കവാറും അവരുടെ രക്തബന്ധ പാത വളരെ ശുദ്ധമായി നിലനിർത്തിരുന്നു എന്ന് തോന്നുന്നു.

ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിൽ ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷത്തിനെ വൻ നീരസത്തോടുകൂടി വിക്ഷിച്ചിരുന്നത് യഥാർത്ഥത്തിൽ ഇവരാരും തന്നെയായിരുന്നില്ല. പോരാത്തതിന്, കുണ്ടോട്ടിയിലെ തങ്ങൾ കുടുംബക്കാരും അവരുടെ പക്ഷക്കാരും വ്യത്യസ്തരായി നിലനിന്നിരുന്നു എന്നും തോന്നുന്നു.

ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിൽ ഇസ്ലാമിക മതത്തിന് ഒരു ഭീകരഭാവം ഉണ്ട് എന്ന് ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷക്കാർക്ക് തിരിച്ചറിവ് വന്നത് കീഴ്ഡന വംശങ്ങൾ കൂട്ടത്തോടെ ഇല്ലാമിലേക്ക് കയറിത്തുടങ്ങിയതോടുകൂടിയാണ്.

ഈ ഭീകര ഭാവം ഇസ്ലാം മതത്തിന്റേയും ആ ആദ്ധ്യാത്മികതയുടെ ആചാര്യ സ്ഥാനത്തുനിൽക്കുന്നുവെന്ന് മനസ്സിലാക്കപ്പെടുന്ന മുഹമ്മദിന്റേയും നൈസർഗ്ഗികമായുള്ള ഒരു മാസനിക സിദ്ധാന്തം ആണ് എന്നാണ് പൊതുവായി അന്നുള്ളതും ഇന്നുള്ളതുമായ ഹൈന്ദവ പക്ഷം ചത്രീകരികരിക്കുന്നത്.

എന്നാൽ ഈ കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിളമാരിലെ വ്യക്തിപരമായുള്ളതും സാമൂഹികമായുള്ളതുമായ പക അവരുടെ സാമൂഹിക അവസ്ഥയുടെ ഒരു പ്രതിഫലനം മാത്രമാകാം.

കാരണം, ഈ ഒരു സാമൂഹിക ഏറ്റുമുട്ടൽ തുടങ്ങുന്നതുവരെ ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷക്കാരും ഇസ്ലാമിലെ ഉന്നത കുടുംബക്കാരും അറബി കച്ചവട സംഘങ്ങളും മറ്റും ഒത്തൊരുമായോടുകൂടിതന്നെയാണ് ജീവിച്ചത്. അവരിലെ പൊതുവായുള്ള ലക്ഷ്യം കീഴ്ജന വ്യക്തികളെ അവർ തളച്ചിടപ്പെട്ട സാമൂഹിക അവസ്ഥയിൽ നിന്നും ഉയരാൻ സമ്മതിക്കരുത് എന്നതുതന്നെയാവാം.

വ്യക്തികൾക്ക് അവർ ജനിച്ചനാൾ മുതൽ സമൂഹത്തിൽ നേരിട്ടു കാണുന്നതും കേൾക്കുന്നതും മറ്റുമായ കാര്യങ്ങൾക്ക് അപ്പുറം അറിവ് ലഭക്കാൻ സാധ്യത കുറവാണ്.

ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിൽ ബ്രാഹ്രണ കുടുംബക്കാരായ ഭൂജന്മികൾ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു. അവരുടെ മേൽനോട്ടക്കാരായ നായർമാർ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു. ഭൂജന്മികൾ നായർമാർക്കും ചിലപ്പോൾ മക്കത്തായ തീയർ വ്യക്തികൾക്കും ഭൂമി പാട്ടത്തിന് നൽകുന്നു. ഈ പാട്ടക്കാർ അവരുടെ കൃഷിയിടത്തിൽ വേലചെയ്യാനായി അടിമവ്യക്തികളെ വിലക്കെടുക്കുകയോ പാട്ടത്തിന് എടുക്കുകയോ ചെയ്യുന്നു.

ഈ അടിമ വ്യക്തികളിൽ വിള്പവ ഭാവം ഇല്ല. അവരിൽ ഉള്ളത് യജമാന ഭക്തിയാണ്.

ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണകാലത്ത് കീഴ്ഡന വ്യക്തികളിൽ പലരും ഇസ്ലാമിലേക്ക് കയറി. അവർ ഭൂമി പാട്ടത്തിന് എടുത്തു തടുങ്ങി. അവരിൽ പലരും കച്ചവടം നടത്തിത്തുടങ്ങി. കാളവണ്ടികളുടേയും ചരക്കുതോണികളുടേയും ഉടമസ്ഥരായി.

ഇവരിൽ വ്യക്തിത്വ പരമായും മാനസികമായും വൻ മുന്നോറ്റം സംഭവിക്കുന്നു.

ഇത് ഏറ്റവും പ്രശ്നമാവുന്നത് നായർ മേലാളന്മാക്കാണ്. കാരണം, പ്രാദേശിക ഭാഷാകോഡുകൾക്ക് ഈ വിധമായുള്ള ഒരു പരിവർത്തനത്തെ ഉൾക്കൊള്ളാൻ ആവില്ല. തിരുവന്തപുരത്തെ ഓട്ടോ ഡ്രൈവർ പോലീസ് ശിപായിയെ നീ എന്ന് സമ്പോധന ചെയ്യുന്നതുപോലുള്ള ഒരു ഭാഷാ കോഡിങ്ങ് പ്രശ്നം ഉയർന്നുവരും.

നായർമാർക്ക് കീഴ്ജന മാപ്പിള വ്യക്തിയെ അവരുടെ അടിമ വ്യക്തിയായിത്തന്നെ കാണാനാണ് ആഗ്രഹം നിലനിൽക്കുക. നായർമാർ അവരുടെ അടിമകളെ പാരമ്പര്യമായി വെട്ടി നുറുക്കി നിയന്ത്രിച്ചവർ തന്നെയാണ്. അങ്ങിനെ ചെയ്യുമ്പോൾ, ആ അടിമ ജനത്തിന് അവരോട് വൻ ആദരവാണ് വളരുക. ഇന്നത്തെ ജനത്തിന് പോലീസുകരോടുള്ള ഭാവം തന്നെ.

ഈ നായർമാർ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണത്തിന്റെ ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥർ ആയാൽ, അവരെ കൃത്യമായി നിയന്ത്രിക്കാൻ ഏകനായ ജില്ലാ കലക്ടർക്ക് ആവില്ല. കാരണം, ഭരണത്തിൽ എല്ലാരും ഈ പ്രദേശത്തുള്ളവർ തന്നെ. അവരുടെ മാനസികവും സാമൂഹികവും ആയ ഭാവങ്ങളും ചിന്തകളും ഗൂഡാലോചനകളും ഭരണയന്ത്രത്തിൽ ഒരു പാടമാതിരി പടർന്നുകിടക്കും.

രണ്ടു പക്ഷത്തുള്ള വ്യക്തികളേയും കുറ്റം പറയാൻ ആവില്ല. അവരിൽ എല്ലാവർക്കും പല തരം വേവലാതികൾ ഉണ്ട്. ഈ വേവലാതികൾ സൃഷ്ടിക്കുന്ന പ്രാദേശിക കാട്ടള ഭാഷ അദൃശ്യമായി നിന്നുകൊണ്ട് വൻ സൗന്ദര്യമുള്ള പാട്ടുകളും ആഘോഷതിമിർപ്പുകളും നടത്തിപ്പുചെയ്യുന്നു.

സാമൂഹിക നേതൃത്വം എന്നത് അത്യന്താപേക്ഷിതമായ ഒരു വ്യക്തിത്വ ഘടകം ആണ് എന്ന് വരേണ്യവ്യക്തികൾക്ക് ഈ ഭാഷ നിത്യവും അറിവും താക്കീതും നൽകുന്നു. അവരുടെ സാമൂഹിക ഉന്നതങ്ങളിൽ പടവെട്ടി നിൽക്കണമെന്ന് മനസ്സിൽ നിശബ്ദമായി മന്ത്രിച്ചു കൊടുക്കുന്നു.

കുറ്റം മുഴുവൻ ആങ്ങ് അകലെ ഉന്നതങ്ങളിൽ നിന്നുകൊണ്ട് സാമൂഹിക പരിവർത്തനത്തിനായി പദ്ധതിയിടുന്ന ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണത്തിന് മേൽ ചാർത്തുക എന്നത് ഒരു വളരെ പ്രായോഗികമായ കാര്യമാണ്. കാരണം, ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് പക്ഷത്തിനെ ജനങ്ങൾക്ക് പറഞ്ഞു മനസ്സിലാക്കിക്കൊടുക്കാൻ പ്രാപ്തരായവരോ താൽപ്പര്യമുള്ളവരോ സമൂഹത്തിൽ ഉണ്ടായിരിന്നിരിക്കില്ല.

ഈ മുകളിൽ എഴുതിയ മിക്ക കാര്യങ്ങളും നേരത്തെ ഈ എഴുത്തിൽ എഴുതിയിട്ടുണ്ട് എന്നാണ് തോന്നുന്നത്.

ഇന്ത്യൻ ഔപചാരിക ചരിത്രകാരന്മാരും തീസിസ് എഴുത്തുകാരും ഇവയിൽ പലതിനും അർഹമായ പരിഗണനൽകാതെ, 1830കളിൽ മാപ്പിള വ്യക്തികൾ നടത്തിയ ആക്രമങ്ങളെ ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് ഭരണത്തിന് എതിരായുള്ള ഒരു സ്വാതന്ത്ര്യ സമര പോരാട്ടമായി വിവരിച്ചുകൊണ്ട് വായനക്കാരേയും ചരിത്രം പഠിക്കാൻ വരുന്നവരേയും വിഡ്ഢികൾ ആക്കുന്ന ഒരു പരിപാടി കാണുന്നുണ്ട് എന്നാണ് തോന്നുന്നത്.

Last edited by VED on Sun Jun 15, 2025 11:45 am, edited 1 time in total.

5. പൊതുശത്രുവിനെ കാണിച്ചുകൊടുക്കാൻ ആയാൽ

ഇസ്ലാം കാഫിർമാരെ ശത്രുക്കളായി കാണുന്നുണ്ട് എന്ന് പറഞ്ഞ് കേൾക്കുന്നു. പണ്ട് കാലങ്ങളിൽ ശത്രുവിനെ കൊന്നുകളയണം എന്ന പൊതുവായുള്ള ഒരു പരിജ്ഞാനം ജനങ്ങളിൽ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നിരിക്കാം. ഈ വിധം ഖുർആനിൽ ഒരു കാഫിർ വിരോധം രേഖപ്പെടുത്തിയിട്ടുണ്ട് എങ്കിൽ അത് ഏത് എന്ത് contextൽ (പശ്ചാത്തലത്തിൽ, സാഹചര്യത്തിൽ) ആണ് പറഞ്ഞിരിക്കുക എന്ന് ഈ എഴുത്തുകാരന് അറിയില്ല.

പണ്ട് കാലങ്ങളിൽ ഈ വിധമായുള്ള പല കാര്യങ്ങളും പല സമൂഹങ്ങളിലും വളരെ വ്യക്തമായിത്തന്നെ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു എന്നു കാണപ്പെടുന്നു.

ഉദാഹരണത്തിന്, അന്യരാജ്യക്കാരെ ആക്രമിക്കുകയും കൊള്ളയടിക്കുകയും ചെയ്യുക എന്നത് ഒരു രാജാവിന്റെ ധർമ്മമാണ് എന്ന് ശാസ്ത്രത്തിൽ പറയുന്നുണ്ട് എന്ന കാര്യം ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കമ്പനി ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥർക്ക് മലബാറിൽ നിന്നും വിവരം ലഭിച്ചിരുന്നു.

Quote from Malabar Manual:

ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കമ്പനി ഇവിടെ science പഠിപ്പിച്ചു തുടങ്ങുന്നതിന് വളരെ മുൻപ് തന്നെ ഈ നാട്ടിൽ ശാസ്ത്രം ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു എന്നതിന് ഒരു തെളിവായി വേണമെങ്കിൽ ഈ വാചകം ഉദ്ദരിക്കാം.

ബൈബ്ൾ പഴയ നിയമത്തിൽ പലവിധ ആക്രമണ ഉദ്ദേശങ്ങളും ഉണ്ട് എന്നാണ് വായിച്ചതായി ഓർമ്മ. ഈ പഴയ നിയമം (Old Testament) എന്ന വിശുദ്ധ ഗ്രന്ഥത്തിന്റെ സാരം ഇസ്ലാം മതക്കാർക്കും ബാദകമാണ് എന്നതും ഇസ്ലാമിന് ആക്രമണ സ്വഭാവം ഉണ്ട് എന്ന ചിന്തക്ക് ഊക്ക് കൂട്ടാം.

എന്നാൽ ക്രിസ്ത്യാനികളിലും കാഫിർ എന്ന പദത്തിനോട് സാമ്യമുള്ള ഒരു പദപ്രയോഗം കാണുന്നുണ്ട്. അത് Heritic എന്ന വാക്കാണ്. യൂറോപ്പിലെ രാജ്യക്കാർ (Spain ഉൾപ്പെടും എന്ന് തോന്നുന്നു) ഈ വിധ Heritic വ്യക്തികളെ കഠിനമായ രീതികളിൽ കൊന്നുകളയുമായിരുന്നു. ക്രിസ്ത്യൻ മതത്തിന്റെ മനുഷ്യസ്നേഹ സങ്കൽപ്പങ്ങളോട് യോജിക്കാത്ത കാര്യമാണ് ഇത്.

ബ്രാഹ്മണ മതത്തിലെ ഭഗവത് ഗീതയിൽ യുദ്ധരംഗത്തിന്റെ ഉള്ളിൽ നിന്നുകൊണ്ട് അർജ്ജുനോട്, ശത്രു പക്ഷത്ത് കാണപ്പെടുന്ന തന്റെ ബന്ധുജനങ്ങളേയും ഗുരുക്കന്മാരേയും തന്റെ ആയുധബലം ഉപയോഗിച്ചുകൊണ്ട് കൊല്ലേണ്ടുന്നതിന്റെ ധാർമ്മിക അടിത്തറയാണ് വളരെ ദീർഘ നേരം ഉപദേശിക്കുന്നത് എന്നു തോന്നുന്നു.

ഈ സാരോപദേശത്തെ ആ യുദ്ധ രംഗത്തിൽ നിന്നും പുറത്തെടുത്തുകൊണ്ട് നോക്കുകയാണ് എങ്കിൽ, ഈ ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷാ പ്രദേശത്ത് വ്യക്തികൾ ഏത് രീതിയിലാണ് ജീവിതത്തിൽ പ്രവർത്തിക്കേണ്ടത് എന്ന ഉപേദശം ആയിരിക്കാം അത് എന്ന് മനസ്സിലാക്കാനായേക്കാം. ഭഗവത് ഗീത വായിച്ചിട്ടില്ലാത്തതിനാൽ കൂടുതൽ വ്യക്തമായി യാതൊന്നു പറയാൻ ആവില്ല.

ഈ വിധമായുള്ള ഉപദേശങ്ങൾ ഏത് തരം ജനത്തിന്റെ കൈകളിൽ ആണ് ലഭിക്കുന്നത് എന്നതിനെ ആശ്രയിച്ചിരിക്കാം അവയെ സ്വന്തം ജീവതത്തിൽ പ്രയോഗിക്കണമോ വേണ്ടയോ എന്ന തീരുമാനം വ്യക്തിയും സമൂഹവും എടുക്കുക.

സമൂഹത്തിലെ വ്യക്തികളെ സ്വന്തം ആജ്ഞാനുവർത്തികളായി അണിനിരത്താൻ പലരും പല മാർഗ്ഗങ്ങൾ ഉപയോഗിച്ചിട്ടുണ്ട്.

അതിൽ ഒന്ന് കമ്മ്യൂണിസം എന്ന പ്രത്യയ ശാസ്ത്രമാണ്. എല്ലാരേയും ഒരേ നിലവാരത്തിൽ സാമൂഹികമായി എത്തിക്കുക എന്ന സങ്കൽപ്പം വളരെ സുഖം നൽകുന്ന ഒരു ആദ്ധ്യാത്മിക ഭാവം തന്നെയാണ്. ഈ ആദ്ധ്യാത്മികതയിൽ വിശ്വാസം ഏൽപ്പിക്കുന്നവർക്ക് മറ്റൊരു ആദ്ധ്യാത്മികതയും വേണ്ടാ എന്ന വാദം തന്നെയുണ്ട്.

ഈ ആദ്ധ്യാത്മിക ചിന്ത ഒരു വശത്ത് നൽക്കുന്നു. വാസ്തവം മറ്റൊരുവശത്താണ്. ഈ വിശ്വാസികൾക്ക് ഇടയിൽ ഉള്ള വാക്കുകളിലെ കഠിനമായ ഉച്ചനീചത്വം പോലും ഇവർക്ക് മാച്ചുകളയാൻ ആവുന്നില്ല. പിന്നെയല്ലെ സമൂഹത്തിലെ ഉച്ചനീചത്വങ്ങളും അസമത്വങ്ങളും ഇവർക്ക് മാച്ചുകളയാണ് ആവുക!

സ്വന്തം ആക്രമിച്ചു പിടിച്ചടക്കൽ പദ്ധതിയിൽ ആളുകളെ അണിനിരത്താൻ പലരും ശ്രമിച്ചിട്ടുണ്ട്. മറാഠി നേതാവായ ശിവാജി ഹൈന്ദവ ആശയങ്ങൾ വിജയകരമായി ഉപയോഗിച്ചിരുന്നു ഇതിനായി. എന്നാൽ ഈ വിധ പദ്ധതികളിൽ സ്വന്തം നാട്ടിലെ അടിമ ജനത്തിനെ മോചിപ്പിക്കാനൊന്നും ശിവാജി ശ്രമിച്ചതായി ആരും പറഞ്ഞുകേട്ടിട്ടില്ല.

മുഗൾ രാജാക്കന്മാരും മറ്റ് ഇസ്ലാമിക രാജാക്കളും നേതാക്കളും ദക്ഷിണേഷ്യയിൽ ഒരു പരുധിക്കപ്പുറം ഇസ്ലാമിക മതം വികാരം സ്വന്തം ആക്രമണ ഉദ്ദേശങ്ങളിൽ ഉപയോഗിച്ചിട്ടില്ലാ എന്നാണ് തോന്നുന്നത്. കാരണം, അവർക്ക് അണിനിരത്തേണ്ട ജനങ്ങളിൽ മിക്കവരും ഇസ്ലാം മതക്കാരായിരുന്നില്ല.

എന്നാൽ ആളുകളെ അണിനിരത്തിയെടുക്കാൻ ഏറ്റവും പ്രാപ്തമായ ആദ്ധ്യാത്മിക പ്രസ്ഥാനം ഇസ്ലാം തന്നെയായിരിക്കാം. കാരണം, വ്യക്തി ജനിച്ചുതുടങ്ങിയ നാൾ മുതൽ ഏതാണ്ട് ഒരു പട്ടാളച്ചിട്ടയിൽ നിത്യജീവിതത്തിൽ പലതും പാലിച്ചും ചെയ്തും ആണ് വളർന്നുവരുന്നത്. ഈ വ്യക്തിയേയും വ്യക്തികളേയും അവരുടെ നേതൃത്വനിരയിൽ നിന്നുകൊണ്ട് അണിനിരത്താൻ പറ്റിയാൽ നേതാവ് വൻ നേതാവായി മാറും. ഭാഷ ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷയും കൂടിയാണെങ്കിൽ ആള് ഏതാണ്ട് ഒരു പട്ടാള കമാണ്ടർ തന്നെ.

എന്നിരുന്നാലും പൊതുശത്രുവിനെ മുന്നിൽ കാട്ടിക്കൊടുക്കാൻ ആയാൽ മാത്രമേ പലപ്പോഴും ആളുകൾ അണിയായി അണിനിരക്കുള്ളു.

ഇവിടെ ഇത്രയും കാര്യം പറഞ്ഞുവന്നത് ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിൽ മാപ്പിളമാർ കാഫിർമാരെ കൊല്ലുന്നത് ഒരു ദിവ്യമായുള്ള കർത്തവ്യമായി കരുതിയിരിക്കാം എന്ന ചിന്താഗതി കാണുന്നതു കൊണ്ടാണ്. ഈ ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിലെ സാമൂഹിക ഭാവം വളർന്നുവരുന്നതിന് മുൻപ് മലബാറുകളിൽ ജീവിച്ചിരുന്ന ഉന്നത കുടുംബക്കാരായ ഇസ്ലാം വ്യക്തികളിൽ ഈവിധമായുള്ള ഒരു കാഫിർമാരെ തട്ടിക്കളയണം എന്ന ഒരു ഭാവം ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നതായി കാണുന്നില്ല.

അതേ സമയം അന്നും കീഴ്ജന വ്യക്തികളായ മുസ്ലിം വ്യക്തികളെ തെല്ലൊരു അറപ്പോടുകൂടിയാണ് ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷം വീക്ഷിച്ചിരുന്നത്.

ഈ അറപ്പോടുകൂടിയുള്ള വീക്ഷണം ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷത്തുള്ളർ അവരുടെ പ്രദേശത്തുള്ള മറ്റ് കീഴ്ജനങ്ങളോടും കാണിച്ചിരുന്നു എന്നതും വാസ്തവം. എന്നാൽ ഇസ്ലാമികരായ കീഴ്ജനങ്ങൾ സ്വന്തം ആജ്ഞാനുവൃത്തികളായി വരാത്തവർ ആയത് ഒരു കഠിനമായ പ്രശ്നം തന്നെയയിരുന്നിരിക്കാം.

ഇവിടെ മറ്റൊരുകാര്യം കൂടി പറയാൻ ഉണ്ട്. Malabar Manualൽ കാണുന്ന ഒരു കാര്യമാണ്:

ആശയം : ചൈനീസ് കച്ചവടക്കാർ പിൻവാങ്ങിയതോടുകൂടി Calicut രാജ്യത്തിൽ മുഹമ്മദീയരുടെ ബലവും സ്വാധീനവും വളർന്നുവന്നു. ഏതാണ്ട് 1490ൽ സമ്പന്നനായ ഒരു മുഹമ്മദീയൻ മലബാറിൽ വന്നു, സാമൂതിരിയെ പലരീതിയിൽ സ്വാധീനിച്ചു പാട്ടിലാക്കി, Calicut രാജ്യത്തിൽ കുറേ മുഹമ്മദീയ പള്ളികൾ കെട്ടാനുള്ള അനുവാദം വാങ്ങിച്ചു.

കായിക ബലം ഉപയോഗിച്ചോ, അതുമല്ലെങ്കിൽ വിശ്വാസം വളർത്തിയോ, ഈ രാജ്യത്തെ ഒരു ഇസ്ലാമിക രാജ്യം ആക്കുമായിരുന്നു എന്ന കാര്യത്തിൽ യാതോരു സംശയവും ഇല്ല. എന്നാൽ ആ കാലത്ത് കുരുമുളകിന്റെ നാട്ടിലേക്ക് ഒരു നേരിട്ടുള്ള പാത കണ്ടെത്താൻ യൂറോപ്പിലെ കച്ചവടക്കാർ ശ്രമിച്ചുകൊണ്ടിരിക്കുകയായിരുന്നു.

END

പണ്ട് കാലങ്ങളിൽ ഈ വിധമായുള്ള പല കാര്യങ്ങളും പല സമൂഹങ്ങളിലും വളരെ വ്യക്തമായിത്തന്നെ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു എന്നു കാണപ്പെടുന്നു.

ഉദാഹരണത്തിന്, അന്യരാജ്യക്കാരെ ആക്രമിക്കുകയും കൊള്ളയടിക്കുകയും ചെയ്യുക എന്നത് ഒരു രാജാവിന്റെ ധർമ്മമാണ് എന്ന് ശാസ്ത്രത്തിൽ പറയുന്നുണ്ട് എന്ന കാര്യം ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കമ്പനി ഉദ്യോഗസ്ഥർക്ക് മലബാറിൽ നിന്നും വിവരം ലഭിച്ചിരുന്നു.

Quote from Malabar Manual:

The Sastra says the peculiar duty of a king is conquest.

ഇങ്ഗ്ളിഷ് കമ്പനി ഇവിടെ science പഠിപ്പിച്ചു തുടങ്ങുന്നതിന് വളരെ മുൻപ് തന്നെ ഈ നാട്ടിൽ ശാസ്ത്രം ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നു എന്നതിന് ഒരു തെളിവായി വേണമെങ്കിൽ ഈ വാചകം ഉദ്ദരിക്കാം.

ബൈബ്ൾ പഴയ നിയമത്തിൽ പലവിധ ആക്രമണ ഉദ്ദേശങ്ങളും ഉണ്ട് എന്നാണ് വായിച്ചതായി ഓർമ്മ. ഈ പഴയ നിയമം (Old Testament) എന്ന വിശുദ്ധ ഗ്രന്ഥത്തിന്റെ സാരം ഇസ്ലാം മതക്കാർക്കും ബാദകമാണ് എന്നതും ഇസ്ലാമിന് ആക്രമണ സ്വഭാവം ഉണ്ട് എന്ന ചിന്തക്ക് ഊക്ക് കൂട്ടാം.

എന്നാൽ ക്രിസ്ത്യാനികളിലും കാഫിർ എന്ന പദത്തിനോട് സാമ്യമുള്ള ഒരു പദപ്രയോഗം കാണുന്നുണ്ട്. അത് Heritic എന്ന വാക്കാണ്. യൂറോപ്പിലെ രാജ്യക്കാർ (Spain ഉൾപ്പെടും എന്ന് തോന്നുന്നു) ഈ വിധ Heritic വ്യക്തികളെ കഠിനമായ രീതികളിൽ കൊന്നുകളയുമായിരുന്നു. ക്രിസ്ത്യൻ മതത്തിന്റെ മനുഷ്യസ്നേഹ സങ്കൽപ്പങ്ങളോട് യോജിക്കാത്ത കാര്യമാണ് ഇത്.

ബ്രാഹ്മണ മതത്തിലെ ഭഗവത് ഗീതയിൽ യുദ്ധരംഗത്തിന്റെ ഉള്ളിൽ നിന്നുകൊണ്ട് അർജ്ജുനോട്, ശത്രു പക്ഷത്ത് കാണപ്പെടുന്ന തന്റെ ബന്ധുജനങ്ങളേയും ഗുരുക്കന്മാരേയും തന്റെ ആയുധബലം ഉപയോഗിച്ചുകൊണ്ട് കൊല്ലേണ്ടുന്നതിന്റെ ധാർമ്മിക അടിത്തറയാണ് വളരെ ദീർഘ നേരം ഉപദേശിക്കുന്നത് എന്നു തോന്നുന്നു.

ഈ സാരോപദേശത്തെ ആ യുദ്ധ രംഗത്തിൽ നിന്നും പുറത്തെടുത്തുകൊണ്ട് നോക്കുകയാണ് എങ്കിൽ, ഈ ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷാ പ്രദേശത്ത് വ്യക്തികൾ ഏത് രീതിയിലാണ് ജീവിതത്തിൽ പ്രവർത്തിക്കേണ്ടത് എന്ന ഉപേദശം ആയിരിക്കാം അത് എന്ന് മനസ്സിലാക്കാനായേക്കാം. ഭഗവത് ഗീത വായിച്ചിട്ടില്ലാത്തതിനാൽ കൂടുതൽ വ്യക്തമായി യാതൊന്നു പറയാൻ ആവില്ല.

ഈ വിധമായുള്ള ഉപദേശങ്ങൾ ഏത് തരം ജനത്തിന്റെ കൈകളിൽ ആണ് ലഭിക്കുന്നത് എന്നതിനെ ആശ്രയിച്ചിരിക്കാം അവയെ സ്വന്തം ജീവതത്തിൽ പ്രയോഗിക്കണമോ വേണ്ടയോ എന്ന തീരുമാനം വ്യക്തിയും സമൂഹവും എടുക്കുക.

സമൂഹത്തിലെ വ്യക്തികളെ സ്വന്തം ആജ്ഞാനുവർത്തികളായി അണിനിരത്താൻ പലരും പല മാർഗ്ഗങ്ങൾ ഉപയോഗിച്ചിട്ടുണ്ട്.

അതിൽ ഒന്ന് കമ്മ്യൂണിസം എന്ന പ്രത്യയ ശാസ്ത്രമാണ്. എല്ലാരേയും ഒരേ നിലവാരത്തിൽ സാമൂഹികമായി എത്തിക്കുക എന്ന സങ്കൽപ്പം വളരെ സുഖം നൽകുന്ന ഒരു ആദ്ധ്യാത്മിക ഭാവം തന്നെയാണ്. ഈ ആദ്ധ്യാത്മികതയിൽ വിശ്വാസം ഏൽപ്പിക്കുന്നവർക്ക് മറ്റൊരു ആദ്ധ്യാത്മികതയും വേണ്ടാ എന്ന വാദം തന്നെയുണ്ട്.

ഈ ആദ്ധ്യാത്മിക ചിന്ത ഒരു വശത്ത് നൽക്കുന്നു. വാസ്തവം മറ്റൊരുവശത്താണ്. ഈ വിശ്വാസികൾക്ക് ഇടയിൽ ഉള്ള വാക്കുകളിലെ കഠിനമായ ഉച്ചനീചത്വം പോലും ഇവർക്ക് മാച്ചുകളയാൻ ആവുന്നില്ല. പിന്നെയല്ലെ സമൂഹത്തിലെ ഉച്ചനീചത്വങ്ങളും അസമത്വങ്ങളും ഇവർക്ക് മാച്ചുകളയാണ് ആവുക!

സ്വന്തം ആക്രമിച്ചു പിടിച്ചടക്കൽ പദ്ധതിയിൽ ആളുകളെ അണിനിരത്താൻ പലരും ശ്രമിച്ചിട്ടുണ്ട്. മറാഠി നേതാവായ ശിവാജി ഹൈന്ദവ ആശയങ്ങൾ വിജയകരമായി ഉപയോഗിച്ചിരുന്നു ഇതിനായി. എന്നാൽ ഈ വിധ പദ്ധതികളിൽ സ്വന്തം നാട്ടിലെ അടിമ ജനത്തിനെ മോചിപ്പിക്കാനൊന്നും ശിവാജി ശ്രമിച്ചതായി ആരും പറഞ്ഞുകേട്ടിട്ടില്ല.

മുഗൾ രാജാക്കന്മാരും മറ്റ് ഇസ്ലാമിക രാജാക്കളും നേതാക്കളും ദക്ഷിണേഷ്യയിൽ ഒരു പരുധിക്കപ്പുറം ഇസ്ലാമിക മതം വികാരം സ്വന്തം ആക്രമണ ഉദ്ദേശങ്ങളിൽ ഉപയോഗിച്ചിട്ടില്ലാ എന്നാണ് തോന്നുന്നത്. കാരണം, അവർക്ക് അണിനിരത്തേണ്ട ജനങ്ങളിൽ മിക്കവരും ഇസ്ലാം മതക്കാരായിരുന്നില്ല.

എന്നാൽ ആളുകളെ അണിനിരത്തിയെടുക്കാൻ ഏറ്റവും പ്രാപ്തമായ ആദ്ധ്യാത്മിക പ്രസ്ഥാനം ഇസ്ലാം തന്നെയായിരിക്കാം. കാരണം, വ്യക്തി ജനിച്ചുതുടങ്ങിയ നാൾ മുതൽ ഏതാണ്ട് ഒരു പട്ടാളച്ചിട്ടയിൽ നിത്യജീവിതത്തിൽ പലതും പാലിച്ചും ചെയ്തും ആണ് വളർന്നുവരുന്നത്. ഈ വ്യക്തിയേയും വ്യക്തികളേയും അവരുടെ നേതൃത്വനിരയിൽ നിന്നുകൊണ്ട് അണിനിരത്താൻ പറ്റിയാൽ നേതാവ് വൻ നേതാവായി മാറും. ഭാഷ ഫ്യൂഡൽ ഭാഷയും കൂടിയാണെങ്കിൽ ആള് ഏതാണ്ട് ഒരു പട്ടാള കമാണ്ടർ തന്നെ.

എന്നിരുന്നാലും പൊതുശത്രുവിനെ മുന്നിൽ കാട്ടിക്കൊടുക്കാൻ ആയാൽ മാത്രമേ പലപ്പോഴും ആളുകൾ അണിയായി അണിനിരക്കുള്ളു.

ഇവിടെ ഇത്രയും കാര്യം പറഞ്ഞുവന്നത് ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിൽ മാപ്പിളമാർ കാഫിർമാരെ കൊല്ലുന്നത് ഒരു ദിവ്യമായുള്ള കർത്തവ്യമായി കരുതിയിരിക്കാം എന്ന ചിന്താഗതി കാണുന്നതു കൊണ്ടാണ്. ഈ ദക്ഷിണ മലബാറിലെ സാമൂഹിക ഭാവം വളർന്നുവരുന്നതിന് മുൻപ് മലബാറുകളിൽ ജീവിച്ചിരുന്ന ഉന്നത കുടുംബക്കാരായ ഇസ്ലാം വ്യക്തികളിൽ ഈവിധമായുള്ള ഒരു കാഫിർമാരെ തട്ടിക്കളയണം എന്ന ഒരു ഭാവം ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നതായി കാണുന്നില്ല.

അതേ സമയം അന്നും കീഴ്ജന വ്യക്തികളായ മുസ്ലിം വ്യക്തികളെ തെല്ലൊരു അറപ്പോടുകൂടിയാണ് ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷം വീക്ഷിച്ചിരുന്നത്.

ഈ അറപ്പോടുകൂടിയുള്ള വീക്ഷണം ബ്രാഹ്മണ പക്ഷത്തുള്ളർ അവരുടെ പ്രദേശത്തുള്ള മറ്റ് കീഴ്ജനങ്ങളോടും കാണിച്ചിരുന്നു എന്നതും വാസ്തവം. എന്നാൽ ഇസ്ലാമികരായ കീഴ്ജനങ്ങൾ സ്വന്തം ആജ്ഞാനുവൃത്തികളായി വരാത്തവർ ആയത് ഒരു കഠിനമായ പ്രശ്നം തന്നെയയിരുന്നിരിക്കാം.

ഇവിടെ മറ്റൊരുകാര്യം കൂടി പറയാൻ ഉണ്ട്. Malabar Manualൽ കാണുന്ന ഒരു കാര്യമാണ്:

it may be safely concluded that, after the retirement of the Chinese, the power and influence of the Muhammadans were on the increase, and indeed there exists a tradition that in 1489 or 1490 a rich Muhammadan came to Malabar, ingratiated, himself with the Zamorin, and obtained leave to build additional Muhammadan mosques. The country would no doubt have soon been converted to Islam either by force or by conviction, but the nations of Europe were in the meantime busy endeavouring to find a direct road to the pepper country of the East.

ആശയം : ചൈനീസ് കച്ചവടക്കാർ പിൻവാങ്ങിയതോടുകൂടി Calicut രാജ്യത്തിൽ മുഹമ്മദീയരുടെ ബലവും സ്വാധീനവും വളർന്നുവന്നു. ഏതാണ്ട് 1490ൽ സമ്പന്നനായ ഒരു മുഹമ്മദീയൻ മലബാറിൽ വന്നു, സാമൂതിരിയെ പലരീതിയിൽ സ്വാധീനിച്ചു പാട്ടിലാക്കി, Calicut രാജ്യത്തിൽ കുറേ മുഹമ്മദീയ പള്ളികൾ കെട്ടാനുള്ള അനുവാദം വാങ്ങിച്ചു.

കായിക ബലം ഉപയോഗിച്ചോ, അതുമല്ലെങ്കിൽ വിശ്വാസം വളർത്തിയോ, ഈ രാജ്യത്തെ ഒരു ഇസ്ലാമിക രാജ്യം ആക്കുമായിരുന്നു എന്ന കാര്യത്തിൽ യാതോരു സംശയവും ഇല്ല. എന്നാൽ ആ കാലത്ത് കുരുമുളകിന്റെ നാട്ടിലേക്ക് ഒരു നേരിട്ടുള്ള പാത കണ്ടെത്താൻ യൂറോപ്പിലെ കച്ചവടക്കാർ ശ്രമിച്ചുകൊണ്ടിരിക്കുകയായിരുന്നു.

END

Last edited by VED on Sun Jun 15, 2025 11:51 am, edited 1 time in total.

6. സമൂഹത്തിൽ സ്ഫോടനാത്മകമായ സാമൂഹിക യന്ത്രകാരകപ്രവർത്തനം

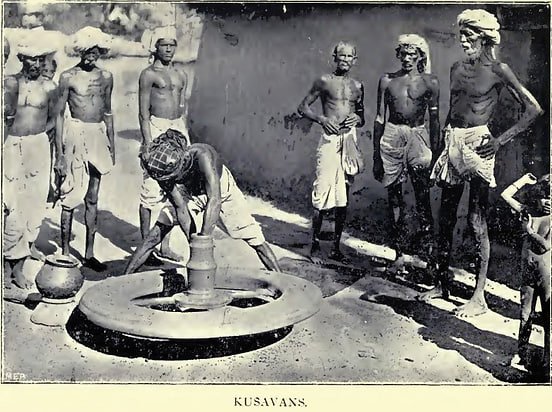

ഒരു പ്രദേശത്ത് കുറേ ചെറുകിട തൊഴിലുകാർ. അവർ ധനവാന്മാരായ പലരുടേയും വീടുകളിൽ വീട്ടുവേല ചെയ്യുന്നു. അവർക്ക് വളരെ തുച്ഛമായ വേതനമാണ് ലഭിക്കുക. അവരെ ആ വീടുകളിൽ ഒരു അഴുക്കുപോലെയാണ് വീട്ടുകാർ കാണുക. കസേരയിൽ ഇരിക്കാൻ പറ്റില്ല. ഭക്ഷണം നിലത്തിരുന്നാണ് കഴിക്കേണ്ടത്.

വീട്ടുകാർ അവരുടെ പഴയ പഴകിയ വസ്ത്രങ്ങൾ ഈ തൊഴിലുകാർക്ക് നൽകും. തൊഴിലുകാരനും ഭാര്യയും കുട്ടികളും ഇവ ധരിക്കും. ഇവർക്ക് അവരുടെ യജമാനന്മാരോട് വൻ മതിപ്പും ഭക്തിയും നിലനിൽക്കും.

അവരിൽ ഒരു ആൾക്ക് ഒരു പുതിയ വീട്ടിൽ തൊഴിൽ ലഭിക്കുന്നു. ആ വീട്ടിൽനിന്നും നല്ല വേതനം ലഭിക്കും. ആ വീട്ടുകാർ ഈ വ്യക്തിക്ക് കൂടുതൽ മെച്ചപ്പെട്ട പരിഗണന നൽകും. ഇരിക്കാൻ കസേര നൽകും. പുതിയ വസ്ത്രങ്ങൾ നൽകും. അയാളുടെ കുട്ടികൾക്ക് സാമൂഹികമായി വളരാനുള്ള സാഹചര്യം ഒരുക്കും. എന്നാൽ ആ ആൾ ആ വിട്ടുകാരുടെ വേലക്കാരൻ മാത്രമാണ്. ഈ ഒരു കാര്യം വളരെ വ്യക്തമായി നിലനിൽക്കും.

ഓരോ വർഷം ചെല്ലുന്തോറും ഈ ആളും അയാളുടെ കുട്ടികളും കുടുബവും സാമൂഹികമായി ഉന്നതങ്ങളിലേക്ക് നീങ്ങിക്കൊണ്ടിരിക്കും.