9. When social inequalities get tumbled upside down!

9. When social inequalities get tumbled upside down!

Written by VED from VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

Previous page - Next page

1. The life struggles of the lower castes

2. The unease caused by uplifting the lower castes

3. Official spaces inaccessible to the lower castes

4. In search of individuals with high mental calibre

5. In British-India, it’s like this, it is like that &c.

6. Artificially and naturally divided, mutually opposing crowds

7. The nuisance that are caste names

8. Forced labour and other issues

9. Manifestations of official arrogance

10. Once in the hands of officials, he or she done for

11. English can bestow social personality and vigour on the downtrodden

12. Caste-based thinking within new Christians

13. Continental Europeans piggyback riding on the English

14. When social hierarchies are turned upside down

15. Elements used to make religious conversion and worship practices attractive

16. Hindu traditions in Travancore

17. A short list of Hindu customs

18. Transcendental software systems and Brahmanical traditions

19. The transcendental software platform of auspicious and inauspicious omens

20. Neither melody nor sweetness shapes human personality

21. Travancore's loyalty and obligation to the English rule in rhe neighbourhood

22. Those who grab huge wage and bribe

23. Integrating primitive regions

24. Protection-giving and protection-seeking links entangled in society

25. Alongside the rise of the lower classes in Travancore, another major issue emerges

26. Various Christian movements operating in southern South Asia

27. A place to relocate the socially advancing lower castes

28. The new digital version of the Malabar Manual and discovering India in history

29. The meticulous precision and efficiency of the English administrative system

30. Keralamahatmyam and Keralolpatti

31. Traditional Malayalam in Malabar and the Malayalam created in Travancore

32. The Malayalam incomprehensible to Travancoreans, and the uneducated Malabaris

33. Fabrications in the Malabar Manual

34. The story of a railway track

35. A detail erased from memory

36. When unbridled!

37. The moral obligation of those who rose from the status of slaves in Travancore

38. A distinct social and occupational culture in Malabar

39. We are not us, but you!

40. Does the nature of language affect skin colour and its perceived quality?

41. On exaggeration and concealment

42. A charismatic leader versus a person who shook the very foundation of an evil society with mere words

43. Those who rallied to seize an empire through verbal acrobatics

44. The legacy of the Guru

45. The limits and beyond of defining the Guru

46. When did revolutions for change in Travancore’s social system begin?

47. When a small person strives to do great things

48. Smart device proficiency and social reform

49. The condition that whatever misdeed a lower-caste person commits, must remain a misdeed even in English

50. On being trapped in the upper echelons of society through reading Sanskrit literature

Previous page - Next page

Vol 1 to Vol 3 have been translated into English by me directly.

From Vol 4 onward, the translation has been done by a translation software. So there can be slight errors in the text.

It was slightly difficult to make the translation software to understand that in Indian languages, there are hierarchy of words everywhere.

From Vol 4 onward, the translation has been done by a translation software. So there can be slight errors in the text.

It was slightly difficult to make the translation software to understand that in Indian languages, there are hierarchy of words everywhere.

1. The life struggles of the lower castes

2. The unease caused by uplifting the lower castes

3. Official spaces inaccessible to the lower castes

4. In search of individuals with high mental calibre

5. In British-India, it’s like this, it is like that &c.

6. Artificially and naturally divided, mutually opposing crowds

7. The nuisance that are caste names

8. Forced labour and other issues

9. Manifestations of official arrogance

10. Once in the hands of officials, he or she done for

11. English can bestow social personality and vigour on the downtrodden

12. Caste-based thinking within new Christians

13. Continental Europeans piggyback riding on the English

14. When social hierarchies are turned upside down

15. Elements used to make religious conversion and worship practices attractive

16. Hindu traditions in Travancore

17. A short list of Hindu customs

18. Transcendental software systems and Brahmanical traditions

19. The transcendental software platform of auspicious and inauspicious omens

20. Neither melody nor sweetness shapes human personality

21. Travancore's loyalty and obligation to the English rule in rhe neighbourhood

22. Those who grab huge wage and bribe

23. Integrating primitive regions

24. Protection-giving and protection-seeking links entangled in society

25. Alongside the rise of the lower classes in Travancore, another major issue emerges

26. Various Christian movements operating in southern South Asia

27. A place to relocate the socially advancing lower castes

28. The new digital version of the Malabar Manual and discovering India in history

29. The meticulous precision and efficiency of the English administrative system

30. Keralamahatmyam and Keralolpatti

31. Traditional Malayalam in Malabar and the Malayalam created in Travancore

32. The Malayalam incomprehensible to Travancoreans, and the uneducated Malabaris

33. Fabrications in the Malabar Manual

34. The story of a railway track

35. A detail erased from memory

36. When unbridled!

37. The moral obligation of those who rose from the status of slaves in Travancore

38. A distinct social and occupational culture in Malabar

39. We are not us, but you!

40. Does the nature of language affect skin colour and its perceived quality?

41. On exaggeration and concealment

42. A charismatic leader versus a person who shook the very foundation of an evil society with mere words

43. Those who rallied to seize an empire through verbal acrobatics

44. The legacy of the Guru

45. The limits and beyond of defining the Guru

46. When did revolutions for change in Travancore’s social system begin?

47. When a small person strives to do great things

48. Smart device proficiency and social reform

49. The condition that whatever misdeed a lower-caste person commits, must remain a misdeed even in English

50. On being trapped in the upper echelons of society through reading Sanskrit literature

Last edited by VED on Sat Aug 09, 2025 12:38 pm, edited 13 times in total.

1. The struggles of the lower castes’ lives

Syrian Christians and Muslims faced no restrictions in walking on most public roads. However, the emergence of a new Christian sect in Travancore grew into a significant social issue.

Around the 1850s, the Diwan made a decision regarding this matter. According to this ruling, this newfound freedom was entirely denied to members of this new Christian sect.

An Ezhava who had converted to Christianity caused an issue by walking near a temple close to the Mission House. The decree that followed was thus: even if an Ezhava converted to Christianity, he remained an Ezhava. He was not permitted to walk on public roads. Instead, he had to traverse the paths through nearby fields, alongside foxes.

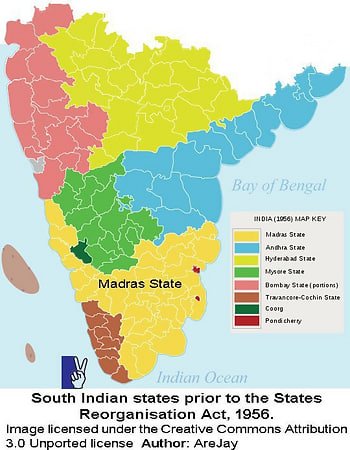

Due to their daily interactions with Pulayas, Pariahs, and others, it can be said that the missionaries of the London Missionary Society also developed a slight social aversion. However, because their skin was white and the English administration in the nearby Madras Presidency closely monitored affairs in Travancore, it can be said that these missionaries faced no significant harm.

In 1870, when an Englishman travelled through a Brahmin village, the locals physically assaulted him. The issue was indeed untouchability. Yet, today, this could be considered worthy of a grand freedom struggle pension. The assailants were merely fined a small amount, and the police dismissed the case.

It seems the English administration in Madras was unaware of today’s freedom struggle pensions. When they learned of this assault, they issued a stern reprimand to the Travancore government. Today, this might be a matter to stir the blood of Indian patriots, for how dare the English scold our king?

To them, one could only say, “Sod off, go find some other work to do!”

The Madras government’s stance was that denying public roads to many people was wrong. They made a proclamation as follows:

The public high streets of all towns are the property, not of any particular caste, but of the whole community; and every man, be his caste or religion what it may, has a right to the full use of them, provided that he does not obstruct or molest others in the use of them; and must be supported in the exercise of that right.

Meanwhile, some officials, beating drums, made a proclamation on the public roads. In the main streets of Trivandrum, no Pulayas (even if Christian) were allowed entry!

This matter came to the attention of the Acting British Resident appointed in Trivandrum at the time. He immediately contacted the royal family. Soon after, a proclamation appeared in the Travancore Government Gazette. The announcement, made with drumbeats in the streets, was declared to have been issued without the royal family’s permission. The gazette also stated that the responsible Tahsildar was punished, and the Provertikar was dismissed from government service.

However, in the next issue of the Travancore Government Gazette, it was announced that the dismissal of the Provertikar was revoked, and His Majesty personally ordered that a fine equivalent to one month’s salary would suffice as punishment.

The Travancore government showed reluctance to print and issue a clear order allowing all people to walk on public roads. As a result, no one knew exactly what the law was.

The missionaries of the London Missionary Society clearly instructed lower-caste converts to Christianity not to attempt to claim any social rights. They were told not to argue, even if asked to step aside, leave, or refrain from entering certain places. The likelihood of being slapped or otherwise assaulted was very high. Moreover, if the police arrested and beat them, the missionaries could do nothing.

If a Pulaya touched a Syrian Christian, the latter would go and wash their body.

When a Nair appeared on the road, a Chovan had to walk on the opposite side, pressed against the edge. If a Brahmin approached, they had to leave the road entirely and step into the fields.

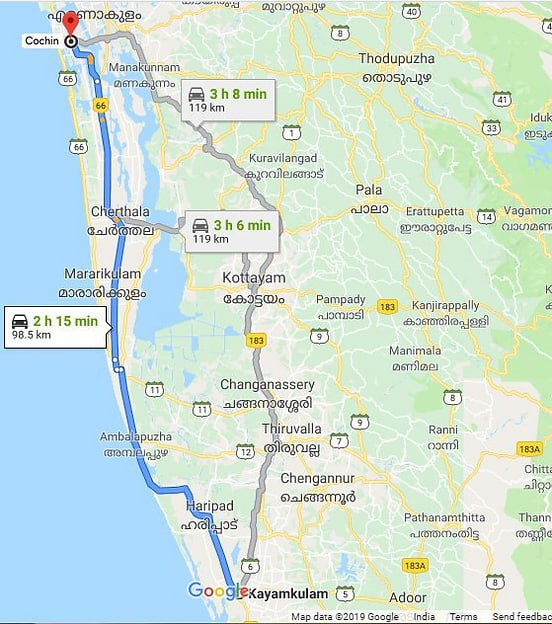

Although missionaries arranged various facilities for the lower castes, using these was extremely difficult for them. Taking a sick lower-caste person to the hospital in Kottayam was nearly impossible. Consequently, a separate hospital was built for the lower castes. However, there was no convenient path for them to reach it. A mere quarter-mile distance via the road required them to walk a great distance through winding field paths.

Among the lower castes, affection for their own children had grown. However, when a child fell ill, they were often unwilling to take them to the hospital, as severe beatings on the way were almost certain. Higher-caste individuals would brutally assault them, striking their faces, ears, and elsewhere, and even trample them on the ground. The condition of the accompanying child was of no concern to the assailants. Such was the fear with which higher castes viewed the proximity of lower castes.

Another issue was the covering of breasts. In the presence of higher castes, the cloth covering the breasts had to be removed and tied around the waist, a clear marker of subservience. However, in southern Travancore, lower-caste converts to Christianity began to refuse to bare their breasts. In a classroom, when the teacher entered, all students stood up—except one.

The reason was simple: in England, students did not show such subservience to teachers. What happened? The teacher labelled the student a great rogue. To curb this roguishness, they had certain methods, which they applied. The same happened to such Christian “rogues.”

Different castes were permitted to wear distinct ornaments. The highest could wear gold, those below them silver, and Pulayas were allowed brass. Hunters, Kuravans, and others could wear necklaces and chest ornaments made of glass beads.

Even so, the lower castes needed official permission to wear any ornaments.

This was the state of affairs in Travancore.

The nearby British-Malabar region was an entirely different world.

Around the 1850s, the Diwan made a decision regarding this matter. According to this ruling, this newfound freedom was entirely denied to members of this new Christian sect.

An Ezhava who had converted to Christianity caused an issue by walking near a temple close to the Mission House. The decree that followed was thus: even if an Ezhava converted to Christianity, he remained an Ezhava. He was not permitted to walk on public roads. Instead, he had to traverse the paths through nearby fields, alongside foxes.

Due to their daily interactions with Pulayas, Pariahs, and others, it can be said that the missionaries of the London Missionary Society also developed a slight social aversion. However, because their skin was white and the English administration in the nearby Madras Presidency closely monitored affairs in Travancore, it can be said that these missionaries faced no significant harm.

In 1870, when an Englishman travelled through a Brahmin village, the locals physically assaulted him. The issue was indeed untouchability. Yet, today, this could be considered worthy of a grand freedom struggle pension. The assailants were merely fined a small amount, and the police dismissed the case.

It seems the English administration in Madras was unaware of today’s freedom struggle pensions. When they learned of this assault, they issued a stern reprimand to the Travancore government. Today, this might be a matter to stir the blood of Indian patriots, for how dare the English scold our king?

To them, one could only say, “Sod off, go find some other work to do!”

The Madras government’s stance was that denying public roads to many people was wrong. They made a proclamation as follows:

The public high streets of all towns are the property, not of any particular caste, but of the whole community; and every man, be his caste or religion what it may, has a right to the full use of them, provided that he does not obstruct or molest others in the use of them; and must be supported in the exercise of that right.

Meanwhile, some officials, beating drums, made a proclamation on the public roads. In the main streets of Trivandrum, no Pulayas (even if Christian) were allowed entry!

This matter came to the attention of the Acting British Resident appointed in Trivandrum at the time. He immediately contacted the royal family. Soon after, a proclamation appeared in the Travancore Government Gazette. The announcement, made with drumbeats in the streets, was declared to have been issued without the royal family’s permission. The gazette also stated that the responsible Tahsildar was punished, and the Provertikar was dismissed from government service.

However, in the next issue of the Travancore Government Gazette, it was announced that the dismissal of the Provertikar was revoked, and His Majesty personally ordered that a fine equivalent to one month’s salary would suffice as punishment.

The Travancore government showed reluctance to print and issue a clear order allowing all people to walk on public roads. As a result, no one knew exactly what the law was.

The missionaries of the London Missionary Society clearly instructed lower-caste converts to Christianity not to attempt to claim any social rights. They were told not to argue, even if asked to step aside, leave, or refrain from entering certain places. The likelihood of being slapped or otherwise assaulted was very high. Moreover, if the police arrested and beat them, the missionaries could do nothing.

If a Pulaya touched a Syrian Christian, the latter would go and wash their body.

When a Nair appeared on the road, a Chovan had to walk on the opposite side, pressed against the edge. If a Brahmin approached, they had to leave the road entirely and step into the fields.

Although missionaries arranged various facilities for the lower castes, using these was extremely difficult for them. Taking a sick lower-caste person to the hospital in Kottayam was nearly impossible. Consequently, a separate hospital was built for the lower castes. However, there was no convenient path for them to reach it. A mere quarter-mile distance via the road required them to walk a great distance through winding field paths.

Among the lower castes, affection for their own children had grown. However, when a child fell ill, they were often unwilling to take them to the hospital, as severe beatings on the way were almost certain. Higher-caste individuals would brutally assault them, striking their faces, ears, and elsewhere, and even trample them on the ground. The condition of the accompanying child was of no concern to the assailants. Such was the fear with which higher castes viewed the proximity of lower castes.

Another issue was the covering of breasts. In the presence of higher castes, the cloth covering the breasts had to be removed and tied around the waist, a clear marker of subservience. However, in southern Travancore, lower-caste converts to Christianity began to refuse to bare their breasts. In a classroom, when the teacher entered, all students stood up—except one.

The reason was simple: in England, students did not show such subservience to teachers. What happened? The teacher labelled the student a great rogue. To curb this roguishness, they had certain methods, which they applied. The same happened to such Christian “rogues.”

Different castes were permitted to wear distinct ornaments. The highest could wear gold, those below them silver, and Pulayas were allowed brass. Hunters, Kuravans, and others could wear necklaces and chest ornaments made of glass beads.

Even so, the lower castes needed official permission to wear any ornaments.

This was the state of affairs in Travancore.

The nearby British-Malabar region was an entirely different world.

Last edited by VED on Sat May 24, 2025 5:54 pm, edited 2 times in total.

2. The unease and other issues arising from uplifting the lower castes

The following statement is found in Native Life in Travancore:

It will now be seen that the free access of the lower classes of the population to Courts of Justice, Government officials, and fairs and markets, however essential to the public peace, security, and prosperity, is still more difficult of attainment.

REV. SAMUEL MATEER wrote this, it must be said, without any awareness of the social conditions created by the feudal languages of this subcontinent.

Feudal languages naturally create a group called the lower castes in any setting. Enabling them to compete with those above them does not foster social peace but rather engenders unrest and insecurity in the system.

When observing feudal language societies, the linguistic codes position different groups in opposing perspectives. From these differing viewpoints, facts and emotional experiences may be perceived quite differently.

The higher castes and their children, who address others merely by name or with terms like avan (lowest he), aval (lowest she), nee (lowest you), eda, or edi, are themselves part of another suppressed social stratum. Such a group cannot be created in pristine-English, as pristine-English does not place individuals or occupational roles at great distances through word codes.

Raising the lower castes to address the higher castes and their children merely by name, or with terms like avan (lowest he), aval (lowest she), nee (lowest you), eda, or edi, is not true social reform. Rather, it is akin to unleashing suppressed, carnivorous wild beasts to seize humans.

From the above, one can grasp a small part of the bestial nature of the social atmosphere created by feudal languages. There are other aspects as well.

I have witnessed instances where younger individuals address much older people in feudal languages merely by name or as nee (lowest you). These relatively older individuals have appeared personally humiliated and socially suppressed.

This phenomenon is entirely absent in pristine-English. I will not delve into the specifics of pristine-English here.

Men and women of various lower-caste levels have faced such personal degradation for ages. However, the social reforms introduced by the London Missionary Society, rather than uplifting them, enable those previously suppressed to suppress the children of the higher castes.

This is a significant issue. From this perspective, elevating individuals from Pariahs and Pulayas to Ezhavas in feudal languages creates great mental distress among those living peacefully above, amounting to sheer roguery.

Words like cherukkan (boy), pennu (lowest girl) in Malayalam, and chekan, pennu, oruthan, oruthi in Malabar, among others, remain derogatory when used for higher castes. Beyond these, various caste names themselves serve as derogatory terms. Compared to the term Boy used for African Americans in the USA, which seems a trivial discrimination in the realm of fairyland, these feudal language terms create significant distortions in numerous word codes. The term Boy in English does not affect codes like he, his, him, she, her, hers, they, their, or them.

In feudal languages, however, each such word creates profound distortions in numerous word codes, manifesting clear physical and mental effects on the individuals defined by them.

There is another matter as well, a personal observation. I have often interacted with those defined as lower in word codes without displaying any sense of superiority or inferiority. Even when others referred to them as nee (lowest you) or avan (lowest he), I avoided such terms and provided them opportunities to sit and converse. While this mental elevation is offered, it does not truly raise them socially. Instead, it creates a mental experience of dragging me downwards in the surrounding environment.

This is a significant matter. Even the reason for not placing a chair in front of the inspector’s desk in a police station lies within this. That, too, is a complex code arrangement, which I hope to address later.

The above is written to highlight the other side of the actions of the London Missionary Society. Their efforts should not have aimed to eradicate castes but to eliminate feudal languages. However, they lacked such insight. Moreover, the Irish, Scottish, and others among them carried social codes akin to those in South Asia. Many are unaware of this simply because the Irish and Scottish have long aligned with England.

South Asians living in England would have similarly transformed over time had modern travel and communication facilities not existed.

Feudal languages create a group called the lower castes in various contexts. While one might casually say English does the same, there is no connection between the two.

In this subcontinent, kitchen maids are typically kept in a state of personal humiliation and suppression through word codes. They are often defined by mere names, nee (lowest you), edi, or aval (lowest she) in many Indian states.

If an external movement uplifts these individuals, training them to sit at the dining table with the household, address the housewife and householder by name, use nee (lowest you), or refer to them as avan (lowest he) or aval (lowest she), the resulting domestic unease is understandable. The English would not comprehend such matters.

Similar issues exist in the Indian military. Indian soldiers may live humiliated before their officers, who, often younger, define them with mere names, nee (lowest you), or avan (lowest he). However, the substantial financial benefits and elevated status compared to the public place these soldiers akin to Nairs under Brahmins. There is a slight error in this analogy, which I will address later.

The general populace remains as inferior castes.

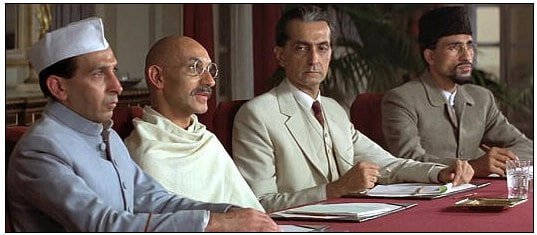

I am keen to discuss the social conditions created by feudal languages in the Indian military. In 2013, I wrote about this in The Shrouded Satanism in Feudal Languages, where these issues were thoroughly discussed. A senior Indian military officer once commented on the book’s accuracy:

Lt Gen H S Panag(R)

The author seems to be an expert in social behaviour! In any hierarchical organisation, social equality is never perfect.

As for state police, the situation is even more complex, which I will attempt to address later.

It will now be seen that the free access of the lower classes of the population to Courts of Justice, Government officials, and fairs and markets, however essential to the public peace, security, and prosperity, is still more difficult of attainment.

REV. SAMUEL MATEER wrote this, it must be said, without any awareness of the social conditions created by the feudal languages of this subcontinent.

Feudal languages naturally create a group called the lower castes in any setting. Enabling them to compete with those above them does not foster social peace but rather engenders unrest and insecurity in the system.

When observing feudal language societies, the linguistic codes position different groups in opposing perspectives. From these differing viewpoints, facts and emotional experiences may be perceived quite differently.

The higher castes and their children, who address others merely by name or with terms like avan (lowest he), aval (lowest she), nee (lowest you), eda, or edi, are themselves part of another suppressed social stratum. Such a group cannot be created in pristine-English, as pristine-English does not place individuals or occupational roles at great distances through word codes.

Raising the lower castes to address the higher castes and their children merely by name, or with terms like avan (lowest he), aval (lowest she), nee (lowest you), eda, or edi, is not true social reform. Rather, it is akin to unleashing suppressed, carnivorous wild beasts to seize humans.

From the above, one can grasp a small part of the bestial nature of the social atmosphere created by feudal languages. There are other aspects as well.

I have witnessed instances where younger individuals address much older people in feudal languages merely by name or as nee (lowest you). These relatively older individuals have appeared personally humiliated and socially suppressed.

This phenomenon is entirely absent in pristine-English. I will not delve into the specifics of pristine-English here.

Men and women of various lower-caste levels have faced such personal degradation for ages. However, the social reforms introduced by the London Missionary Society, rather than uplifting them, enable those previously suppressed to suppress the children of the higher castes.

This is a significant issue. From this perspective, elevating individuals from Pariahs and Pulayas to Ezhavas in feudal languages creates great mental distress among those living peacefully above, amounting to sheer roguery.

Words like cherukkan (boy), pennu (lowest girl) in Malayalam, and chekan, pennu, oruthan, oruthi in Malabar, among others, remain derogatory when used for higher castes. Beyond these, various caste names themselves serve as derogatory terms. Compared to the term Boy used for African Americans in the USA, which seems a trivial discrimination in the realm of fairyland, these feudal language terms create significant distortions in numerous word codes. The term Boy in English does not affect codes like he, his, him, she, her, hers, they, their, or them.

In feudal languages, however, each such word creates profound distortions in numerous word codes, manifesting clear physical and mental effects on the individuals defined by them.

There is another matter as well, a personal observation. I have often interacted with those defined as lower in word codes without displaying any sense of superiority or inferiority. Even when others referred to them as nee (lowest you) or avan (lowest he), I avoided such terms and provided them opportunities to sit and converse. While this mental elevation is offered, it does not truly raise them socially. Instead, it creates a mental experience of dragging me downwards in the surrounding environment.

This is a significant matter. Even the reason for not placing a chair in front of the inspector’s desk in a police station lies within this. That, too, is a complex code arrangement, which I hope to address later.

The above is written to highlight the other side of the actions of the London Missionary Society. Their efforts should not have aimed to eradicate castes but to eliminate feudal languages. However, they lacked such insight. Moreover, the Irish, Scottish, and others among them carried social codes akin to those in South Asia. Many are unaware of this simply because the Irish and Scottish have long aligned with England.

South Asians living in England would have similarly transformed over time had modern travel and communication facilities not existed.

Feudal languages create a group called the lower castes in various contexts. While one might casually say English does the same, there is no connection between the two.

In this subcontinent, kitchen maids are typically kept in a state of personal humiliation and suppression through word codes. They are often defined by mere names, nee (lowest you), edi, or aval (lowest she) in many Indian states.

If an external movement uplifts these individuals, training them to sit at the dining table with the household, address the housewife and householder by name, use nee (lowest you), or refer to them as avan (lowest he) or aval (lowest she), the resulting domestic unease is understandable. The English would not comprehend such matters.

Similar issues exist in the Indian military. Indian soldiers may live humiliated before their officers, who, often younger, define them with mere names, nee (lowest you), or avan (lowest he). However, the substantial financial benefits and elevated status compared to the public place these soldiers akin to Nairs under Brahmins. There is a slight error in this analogy, which I will address later.

The general populace remains as inferior castes.

I am keen to discuss the social conditions created by feudal languages in the Indian military. In 2013, I wrote about this in The Shrouded Satanism in Feudal Languages, where these issues were thoroughly discussed. A senior Indian military officer once commented on the book’s accuracy:

Lt Gen H S Panag(R)

The author seems to be an expert in social behaviour! In any hierarchical organisation, social equality is never perfect.

As for state police, the situation is even more complex, which I will attempt to address later.

Last edited by VED on Sat May 24, 2025 5:54 pm, edited 1 time in total.

3. Official spaces inaccessible to the lower castes

The English viewed the affairs of Travancore as steeped in superstition in every respect. However, they had no knowledge of how powerfully the linguistic codes of feudal languages influenced these social matters.

Most official buildings in the kingdom were located in the vicinity of temples. These official buildings and their activities were deeply intertwined with Hindu (Brahmin) rituals, idols, deities, and the like. Consequently, lower-caste groups feared even approaching the premises of these official buildings. They were denied entry in many places. Moreover, all officials were from higher castes (Hindus and their followers), making it intolerable for them to have the lower castes come near.

While blaming higher castes for their casteism, it must not be forgotten that even today, officials in this country find the ordinary lower-caste citizen utterly repulsive. This repulsion is not merely caste-based; rather, when a person of single-digit status approaches one of crore-digit status, the latter experiences not only disgust and aversion but also a depletion of vital energy. This is the reality.

I recall a private remark made some years ago by a judge to a relative of his.

In the morning, the police would bring in the ‘rogues’ they had apprehended. The judge’s complaint was that merely seeing the faces of these rogues brought bad fortune. This man was not from a higher caste, yet he believed that encountering the common inferior caste in the morning was inauspicious. Even though the caste system has nominally vanished, things remain much the same. This judge, an official who should not prejudge those brought by the police, is duty-bound to listen to their statements as a government employee. Yet, he seems to have forgotten this entirely.

Returning to Travancore, witnesses could not come to court, so the court would occasionally go to them—but not too close.

The witness would stand far away. The court clerk would read out the question, which a policeman standing some distance away would shout. The witness, hearing the question from afar, would respond loudly. The policeman would then shout the response, which the court would hear.

When the English movement provided facilities, advice, and senior officials to establish courts of justice in Travancore, this was the form the courts took.

Consider this statement from an English newspaper in British-India at the time, describing court proceedings in Travancore and Cochin:

It is very amusing to watch a case of this description going on, for the Gumashta (clerk) of the cutcherry has to cry out at the top of his voice every question, and the witnesses or defendants, as the case may be, have in turn to respond to them, by as loud yells, so that all the proceedings are not only audible to those in court, but to those out of and far from it, presenting a scene more like a serious quarrel than a court of law.

Lower-caste petitioners had to wait for days in the sun and rain, far from the court verandah. They were not allowed to cover their heads, as that would be seen as defiance by the lower castes. After standing like this for days, the court might one day agree to hear their petition.

When the English side’s calls to regulate such roguish court proceedings went unheeded, one day the British Resident in Travancore directly issued an order prohibiting these practices. To those studying India’s heroic freedom struggle today, this act by the British Resident would spark great resentment. Who is this British Resident to issue orders in our land, eh?

The reality seems to be that Travancore’s official class paid scant regard to this order. It must be said that these roguish officials were worthy of freedom struggle pensions.

The situation in Travancore was altogether complex. The royal family likely desired to improve the land and eradicate caste issues. However, for the Brahmins, temple-dwellers, and Nairs who upheld the royal family, this was unthinkable.

At the same time, the royal family cooperated with movements like the London Missionary Society. However, such movements were not permitted to operate in British-India. Yet, these movements approached the British-Indian government for their needs, a connection that likely protected them from harm in Travancore.

I write this based on reading an account by Rev. J. H. Hawksworth, a Christian evangelist, who recorded an incident in 1855:

To prevent Pulayas from attending a Christian school, landlords burned down the school building twice. A slave who came to study there was severely beaten and fell unconscious. According to the social customs of that kingdom, this was not considered a grave act of violence, as beating a slave was not seen as a crime by anyone. When the English hear the word ‘slave’ today, they might imagine slaves in Europe or the USA as depicted in Hollywood films—individuals with great personal dignity.

In reality, beating a Pariah or Pulaya slave was locally understood as akin to beating a stray dog. The English movement could not conceive of a person or animal in such a degraded slot, as their language’s words like You, He, and She have no such degraded slot.

The landlord of the beaten slave intervened, urging him to file a complaint with the police. But the slave was deeply doubtful. How could he file a complaint at the police station? He had to shout his complaint from a distance. Where was a suitable place for that?

Another slave, well-acquainted with the area where the police station stood, was permitted to accompany him. To avoid being seen by other landlords, the two travelled through fields and forests. However, at one point, a member of a landlord family caught them. One slave escaped, but the other received a severe beating and other assaults.

A few days later, they set out again with the same plan and were again caught by assailants and beaten. However, after some time, they reached near the police station and lodged a complaint by shouting from a distance.

Justice matters reached only this far. They did not progress further. The beating was all that remained.

Rev. George Matthan, another evangelist, recounted a different incident in 1856: a slave celebrating the Sabbath day was brutally beaten by a landlord. Rev. George Matthan considered filing a complaint with the police, but the courts were riddled with corruption. Moreover, officials were strongly opposed to uplifting the slave population, so no complaint was filed.

The English administration in Madras exerted great pressure to make several government buildings accessible to the lower castes. Nevertheless, the reality is that there were social dynamics the English could not comprehend.

If the eyes, facial expressions, furrowed brows, body language displayed through cheeks, gestures, and the like of the lower castes do not radiate subservience in feudal language codes, what then would they radiate?

If the inferior does not display subservience, what emerges is defiance. The English word for dhikkaram (defiance) is impertinence. However, this word cannot capture the explosive outburst triggered when an inferior says, “Nee poda” (lowest you, get lost) to a person of social dignity with a refined demeanour, whether through words, eye language, or body language.

Moreover, when lower castes look at women of higher castes with clear vulgarity or crude intent, indicated through words, a drooling mouth, or a glint in the eye, the shocking upheaval in linguistic codes causes a social degradation in the individual, their family, and kin, about which the English had no means of understanding.

This is another facet of social reform in feudal language societies.

In the Indian military, training is designed to prevent such behaviours among sepoy soldiers, as their absence could lead to mental derangement among officers. Such training did not exist in the old English military, it must be understood. I cannot speak to the present situation, as that place is now being overtaken by feudal language speakers.

Last edited by VED on Sat May 24, 2025 5:55 pm, edited 1 time in total.

4. In search of individuals with high mental calibre

The Madras Presidency government persistently pressured the Travancore royal family to implement significant social reforms. However, looking back, it must be understood that the English administration in British-India lacked knowledge of the complex social environment in South Asia.

A large population was controlled through slavery and caste-based oppression. The English side had no thoughts on where or how to rein in the forward movement of those released from such suppression.

It is those who speak feudal languages who need to be set free. Matters are not as they appear in English. When avan (lowest he) becomes addeham (highest he), the new addeham eagerly seeks to suppress the old addeham, turning them into a new avan. The English side had little understanding of this possibility then, and none today.

Rev. Samuel Mateer compares Travancore with British-India. He mentions that a museum was built in Trivandrum at great expense, constructed to earn the praise of European individuals. He also notes that the Murajapam festival, held every six years by Brahmin elites at the Padmanabhaswamy Temple, incurred significant financial costs.

Mateer firmly states that just a fraction of this lavish expenditure would suffice to build all district courts in Travancore in a manner accessible to everyone, aligned with the emerging social context.

Alternatively, he says, hundreds of schools could be built across the kingdom with the money squandered. However, the social progress Mateer envisions would not necessarily result from building such schools—a separate issue.

Speaking of wasteful expenditure, only a small percentage of the crores of rupees India spends on military purposes today would suffice to build splendid facilities for the common man on public roads across the country. Yet, it seems no one thinks this way. The common man in India is, in itself, a highly complex entity.

Merely building facilities is not enough; there must also be thought about where to direct the populace. The population is surging towards vast numbers. Simply providing more facilities could soon turn population growth into a major social disaster. The proliferation of people lacking quality is indeed a significant problem. The question of what constitutes quality arises here, but I won’t delve into that.

What Rev. Samuel Mateer failed to understand is that in British-India, all groups had all kinds of freedoms, and anyone could aspire to government jobs. What would be the issue if Travancore did the same?

The Travancore royal family faced another problem. They struggled to find trustworthy individuals with cultural values and free from corruption to appoint as officials, even if they searched with a fine-tooth comb.

Consequently, many senior officials appointed were local British-Indian officers from South Asia, borrowed with the English administration’s permission. This led to another issue: in British-India, individuals from lower castes could hold high positions in the administrative system, but appointing such individuals in Travancore would cause a massive social uproar. For example, in British-Malabar, senior officials might include Marumakkathayam or Makkathayam Tiyyas. If such individuals were appointed to high posts in Travancore, it would spark a social explosion.

However, before a system of public examinations based on English language proficiency was established in British-Malabar, the English Company administration faced significant issues with local chieftains. These chieftains and other landlords were the early officials. When the Principal Collector asked for land records or revenue details, these individuals would deliberately send falsified accounts. Often, these records were baseless, much like students today copying notes from one another in schools or colleges. Chieftains amassed great wealth through such official manipulations.

The problem of not being able to trust anyone in one’s own country for official roles remains a widespread issue in India today. However, it is likely true that the English administration’s system of selecting officials through public examinations in English did not face this issue significantly. The backdrop to this was that local officials in British-India during English rule sought to emulate their superior English officers.

Today, most Indian officials try to emulate their superior officers and politicians.

These two different forms of emulation instil distinct cultural values in individuals, shaping two different types of people.

Mateer himself hints at one or two problems that arise when lower-caste individuals are placed in high government positions. In Travancore, government responsibilities related to religion, spirituality, temple administration, and general governance were intertwined. Thus, individuals of lower caste status could not be appointed to such roles.

The Travancore State Manual contains this statement:

He was the junior of the two Dewan Peishcars, but the Senior one Raman Menoven (Menon) was in the north of Travancore and being a Soodra could not have conducted the great religious festival then celebrating at Trivandrum.

Yet, Nairs were granted access to all other positions.

When Colonel Munro was appointed Dewan of Travancore for a time, he appointed some individuals from affluent Syrian Christian families to high-quality government jobs. However, when recording temple expenditure accounts or measuring grains and other items, they had to stand outside the temple at a specified distance to perform these tasks.

A greater problem loomed for those socially elevated. If lower-caste individuals entered high official positions, the higher castes would have to stand before such degraded individuals, bowing or otherwise. This was unthinkable, as the language was feudal. Even today, ordinary people cannot address officials as ningal (middle-level you) in this language.

This problem has been made possible by today’s Indian official class. No matter how low-status an individual is appointed to an official role, the common man must bow before them. When those who think and act in feudal languages become officials, this is the issue—not caste. Much more needs to be said on this, but that can come later.

The British-Indian administration took great care to prevent low-status individuals from forcing the public to bow in such ways. Their solution was to bar low-status individuals from entering high official ranks. The sieve they used to select high-quality individuals for top positions was proficiency in splendid English.

Looking at it this way, things today are the opposite. The current government policy is to appoint the least qualified to top official roles. The public must bow before these utterly low-quality individuals.

Last edited by VED on Sat May 24, 2025 5:55 pm, edited 2 times in total.

5. In British-India, it’s like this, it is like that &c.

Rev. Samuel Mateer constantly mentions in Native Life in Travancore that things are done this way and that way in British-India, advocating that such practices should be implemented in Travancore. However, it seems he lacked clear understanding of many matters.

Mateer claims that in British-India, no value was given to caste-based thinking, and government jobs and education were universally opened to all, causing no issues for higher castes.

In reality, this may not have been entirely true. Moreover, the idea of providing extensive education to all in British-India became a significant financial burden for England. By 1869, over the previous decade, this cost had risen from £341,111 to £912,200, a sum England had to bear directly.

The primary benefit of this education went to higher castes. Many insisted their children receive education in English. Meanwhile, in villages and small towns, local leaders opposed starting schools but collected government funds for their expenses.

In 1869, Lord Mayo, the British-Indian Governor-General, declared that free education would not be exclusive to higher castes and that all castes would have access. This policy became a major issue, fostering deep resentment among many higher castes towards English rule.

In Travancore, if Ezhava children were admitted to schools, there was a threat that children from Nair and higher castes would leave those schools. However, Mateer’s claim that opening public education to lower castes in British-India caused no such issues was not entirely accurate.

In places like Tellicherry, many higher castes withdrew from education altogether, one might say. In Tellicherry, some Marumakkathayam Tiyya families greatly benefited from this new education system, while it adversely affected many ordinary Nair families. Financially capable higher castes sent their children to Samoothiri-run schools in Calicut, South Malabar. Some less affluent families kept their children out of formal education entirely.

Some of these children later joined government service as sepoys. Some of their officers were Marumakkathayam Tiyya individuals. For Nair youths who became sepoys, the nightmares they saw in childhood seemed to materialize as physical reality when they grew up.

In Travancore, the London Missionary Society was privately determined to educate lower-caste and higher-caste children in the same schools. Though they opened schools exclusively for children of lower castes, including those who converted to Christianity, they were not satisfied with such segregated education.

In truth, while English nations managed to integrate diverse groups socially and otherwise, in African nations like South Africa and Rhodesia, English descendants themselves opposed such integration. Many subtle yet powerful social links related to this need discussion, but I won’t delve into that now.

In this subcontinent, social systems are determined by feudal language codes. Elevating the lower castes merely shifts individuals between social tiers without significantly altering the links that shape social relationships. Moreover, when lower castes rise, they feel no gratitude or loyalty towards the royal family that granted them opportunities for the first time in history. Instead, their minds foster increasing resentment, hostility, and competitiveness.

A prime example is what happened on Travancore’s streets as lower castes were progressively freed. With each new freedom, they intensified riots on the streets. Ultimately, in 1946, lower castes in Punnapra and Vayalar, near Alleppey, created a massive uprising. They killed a police inspector who came to negotiate. Travancore’s armed police responded with fierce vengeance, shooting and killing many.

It was linguistic codes that instilled bestiality in their minds. Without changing these codes, society cannot achieve peace.

When Nehru threatened to send the army to seize Travancore, it’s worth noting that none of the groups the royal family had uplifted from the social gutter declared support for them. Instead, they acted treasonously towards their own king and kingdom. Those from the northern parts of the peninsula subjugated the kingdom!

Mateer claims that in British-India, no value was given to caste-based thinking, and government jobs and education were universally opened to all, causing no issues for higher castes.

In reality, this may not have been entirely true. Moreover, the idea of providing extensive education to all in British-India became a significant financial burden for England. By 1869, over the previous decade, this cost had risen from £341,111 to £912,200, a sum England had to bear directly.

The primary benefit of this education went to higher castes. Many insisted their children receive education in English. Meanwhile, in villages and small towns, local leaders opposed starting schools but collected government funds for their expenses.

In 1869, Lord Mayo, the British-Indian Governor-General, declared that free education would not be exclusive to higher castes and that all castes would have access. This policy became a major issue, fostering deep resentment among many higher castes towards English rule.

In Travancore, if Ezhava children were admitted to schools, there was a threat that children from Nair and higher castes would leave those schools. However, Mateer’s claim that opening public education to lower castes in British-India caused no such issues was not entirely accurate.

In places like Tellicherry, many higher castes withdrew from education altogether, one might say. In Tellicherry, some Marumakkathayam Tiyya families greatly benefited from this new education system, while it adversely affected many ordinary Nair families. Financially capable higher castes sent their children to Samoothiri-run schools in Calicut, South Malabar. Some less affluent families kept their children out of formal education entirely.

Some of these children later joined government service as sepoys. Some of their officers were Marumakkathayam Tiyya individuals. For Nair youths who became sepoys, the nightmares they saw in childhood seemed to materialize as physical reality when they grew up.

In Travancore, the London Missionary Society was privately determined to educate lower-caste and higher-caste children in the same schools. Though they opened schools exclusively for children of lower castes, including those who converted to Christianity, they were not satisfied with such segregated education.

In truth, while English nations managed to integrate diverse groups socially and otherwise, in African nations like South Africa and Rhodesia, English descendants themselves opposed such integration. Many subtle yet powerful social links related to this need discussion, but I won’t delve into that now.

In this subcontinent, social systems are determined by feudal language codes. Elevating the lower castes merely shifts individuals between social tiers without significantly altering the links that shape social relationships. Moreover, when lower castes rise, they feel no gratitude or loyalty towards the royal family that granted them opportunities for the first time in history. Instead, their minds foster increasing resentment, hostility, and competitiveness.

A prime example is what happened on Travancore’s streets as lower castes were progressively freed. With each new freedom, they intensified riots on the streets. Ultimately, in 1946, lower castes in Punnapra and Vayalar, near Alleppey, created a massive uprising. They killed a police inspector who came to negotiate. Travancore’s armed police responded with fierce vengeance, shooting and killing many.

It was linguistic codes that instilled bestiality in their minds. Without changing these codes, society cannot achieve peace.

When Nehru threatened to send the army to seize Travancore, it’s worth noting that none of the groups the royal family had uplifted from the social gutter declared support for them. Instead, they acted treasonously towards their own king and kingdom. Those from the northern parts of the peninsula subjugated the kingdom!

Last edited by VED on Sat May 24, 2025 5:55 pm, edited 1 time in total.

6. Artificially and naturally separated, mutually opposing sections of population

For their operation, the Travancore government allocates one-tenth of the education budget as a grant.

It does not seem that the higher sections of population were particularly pleased with the lower sections advancing in knowledge and formal education.

One thing the London Missionary Society failed to clearly understand is that the education they promote is in Malayalam. It appears they have also endeavoured to develop and refine this language. There is a sense that they imported a vast vocabulary from Sanskrit.

Education through Malayalam is not akin to teaching English. Providing advancement to the lower sections through Malayalam equips them to suppress the higher sections using the same linguistic codes, granting them social mobility, opportunities, and status. Moreover, the newly empowered lower sections may use their newfound abilities to oppress those among themselves who have not achieved similar social advancement. This does not foster peace or refinement in society. This insight seems to have eluded the English Missionary Society.

However, the local higher sections likely viewed the Missionary Society’s activities as, “What nonsense are these pompous fools carrying out?”

The Society had other such shortcomings. One was their lack of awareness of the clear distinction between Continental Europeans and the English. The English and England’s historical class enemies were, in fact, Continental Europeans.

This same issue exists between the English and the Celtic-speaking peoples within Britain—Irish, Scots, and Welsh. Yet, due to the common light skin colour, when the English travel to Asia, Africa, or elsewhere, they are often identified with the same superior status as Europeans. This is a grave misidentification and a trap. I feel more can be said on this later.

In Native Life in Travancore, there is a sentence:

The Travancoreans are not a nation, but a congeries of artificially and widely-separated, for the most part mutually opposing, sections of population.

This reality persists in India today. However, the lower sections do not clearly recognise this. Even if they did, they may not be able to do much about it. Today’s higher sections—government employees and their organisations—use local feudal linguistic codes to keep the ordinary Indian citizen in a lower position. The unspoken aim of compulsory formal education is to mentally confine them through language, preventing their escape from this position. The feudal language spoken by the lower sections makes it difficult for them to unite or cooperate voluntarily. They are prone to intense rivalry and backstabbing among themselves. Capturing this social and emotional dynamic created by feudal language in English is indeed challenging.

In Travancore, through the direct efforts of English Christian missionaries and pressure from the English administration in Madras, the lower sections began to gain freedom from various forms of exploitation. For instance, some communities were liberated from the obligation to supply firewood to Brahmin dining halls attached to major temples, either for free or at a nominal price. It must be noted that such temples were immensely wealthy.

However, to keep the lower sections perpetually shaken and unsettled, words like enthadi, nee, avan, and aval were used to facilitate attacks that hindered the development of their personality and dignity, compelling them to publicly display subservience. The lower sections, both men and women, were left with stunted personalities! The children of those with stunted personalities inherit diminished personalities! This also aids in maintaining societal regimentation. If this structure breaks, the lower sections may behave defiantly.

There is much to write about the legal reforms occurring in Travancore, but there is no plan for that now. However, many official powers were restrained due to strong external influence from the English Company. One such regulation, as recorded in the Travancore State Manual, states: and on no account shall a female be detained for a night.

Yet, as far as the lower sections were concerned, the police system in Travancore was generally a terrifying institution, as noted in various sources. In Christian activities involving the lower sections, the police often intervened without provocation. Chasing away those who came to hear religious discussions or receive medicine seems to have been a form of amusement for the police and a means of enhancing their sense of authority.

A policeman arrested a local individual of high character and standing, a Mission Catechist, for allegedly cutting bamboo from the forest without government permission and detained him in a lockup for some time. When Rev. Samuel Mateer records this incident, he omits a key detail: the police likely addressed this highly respected individual as nee and referred to him as avan. Once such words are used, the likelihood of physical assault—slaps to the face, choking, or kicks to the stomach—increases significantly, and this should be documented. Even if no physical assault occurs, the verbal blow of such words strikes a person of high standing as if all these had happened, leaving their body numb.

Nevertheless, the London Missionary Society actively promoted this harmful language. They did not adopt the British-Indian government’s stance of promoting English. The underlying motive may have been the mental insecurities sprouting in the minds of newly emerging local Christian leaders. The steep hills, valleys, and pits of the social landscape could be levelled into a pristine plateau by English. This may not have been appealing to the newly risen Christian leaders. There is much to say on this too, if the opportunity arises.

Moreover, Christian hymns in the local language have such charm and beauty! Hearing just a snippet makes one pause in awe. The mind scatters with pearls, the body trembles with goosebumps, and poetic thoughts of divinity awaken. A subtle sweetness fills communal prayers, untouched by the social atmosphere.

The traditional language of Travancore was Tamil. Moreover, the language of many lower sections was something else entirely, not Malayalam. When choosing to teach a new language, English would have been the most desirable option by far.

It does not seem that the higher sections of population were particularly pleased with the lower sections advancing in knowledge and formal education.

One thing the London Missionary Society failed to clearly understand is that the education they promote is in Malayalam. It appears they have also endeavoured to develop and refine this language. There is a sense that they imported a vast vocabulary from Sanskrit.

Education through Malayalam is not akin to teaching English. Providing advancement to the lower sections through Malayalam equips them to suppress the higher sections using the same linguistic codes, granting them social mobility, opportunities, and status. Moreover, the newly empowered lower sections may use their newfound abilities to oppress those among themselves who have not achieved similar social advancement. This does not foster peace or refinement in society. This insight seems to have eluded the English Missionary Society.

However, the local higher sections likely viewed the Missionary Society’s activities as, “What nonsense are these pompous fools carrying out?”

The Society had other such shortcomings. One was their lack of awareness of the clear distinction between Continental Europeans and the English. The English and England’s historical class enemies were, in fact, Continental Europeans.

This same issue exists between the English and the Celtic-speaking peoples within Britain—Irish, Scots, and Welsh. Yet, due to the common light skin colour, when the English travel to Asia, Africa, or elsewhere, they are often identified with the same superior status as Europeans. This is a grave misidentification and a trap. I feel more can be said on this later.

In Native Life in Travancore, there is a sentence:

The Travancoreans are not a nation, but a congeries of artificially and widely-separated, for the most part mutually opposing, sections of population.

This reality persists in India today. However, the lower sections do not clearly recognise this. Even if they did, they may not be able to do much about it. Today’s higher sections—government employees and their organisations—use local feudal linguistic codes to keep the ordinary Indian citizen in a lower position. The unspoken aim of compulsory formal education is to mentally confine them through language, preventing their escape from this position. The feudal language spoken by the lower sections makes it difficult for them to unite or cooperate voluntarily. They are prone to intense rivalry and backstabbing among themselves. Capturing this social and emotional dynamic created by feudal language in English is indeed challenging.

In Travancore, through the direct efforts of English Christian missionaries and pressure from the English administration in Madras, the lower sections began to gain freedom from various forms of exploitation. For instance, some communities were liberated from the obligation to supply firewood to Brahmin dining halls attached to major temples, either for free or at a nominal price. It must be noted that such temples were immensely wealthy.

However, to keep the lower sections perpetually shaken and unsettled, words like enthadi, nee, avan, and aval were used to facilitate attacks that hindered the development of their personality and dignity, compelling them to publicly display subservience. The lower sections, both men and women, were left with stunted personalities! The children of those with stunted personalities inherit diminished personalities! This also aids in maintaining societal regimentation. If this structure breaks, the lower sections may behave defiantly.

There is much to write about the legal reforms occurring in Travancore, but there is no plan for that now. However, many official powers were restrained due to strong external influence from the English Company. One such regulation, as recorded in the Travancore State Manual, states: and on no account shall a female be detained for a night.

Yet, as far as the lower sections were concerned, the police system in Travancore was generally a terrifying institution, as noted in various sources. In Christian activities involving the lower sections, the police often intervened without provocation. Chasing away those who came to hear religious discussions or receive medicine seems to have been a form of amusement for the police and a means of enhancing their sense of authority.

A policeman arrested a local individual of high character and standing, a Mission Catechist, for allegedly cutting bamboo from the forest without government permission and detained him in a lockup for some time. When Rev. Samuel Mateer records this incident, he omits a key detail: the police likely addressed this highly respected individual as nee and referred to him as avan. Once such words are used, the likelihood of physical assault—slaps to the face, choking, or kicks to the stomach—increases significantly, and this should be documented. Even if no physical assault occurs, the verbal blow of such words strikes a person of high standing as if all these had happened, leaving their body numb.

Nevertheless, the London Missionary Society actively promoted this harmful language. They did not adopt the British-Indian government’s stance of promoting English. The underlying motive may have been the mental insecurities sprouting in the minds of newly emerging local Christian leaders. The steep hills, valleys, and pits of the social landscape could be levelled into a pristine plateau by English. This may not have been appealing to the newly risen Christian leaders. There is much to say on this too, if the opportunity arises.

Moreover, Christian hymns in the local language have such charm and beauty! Hearing just a snippet makes one pause in awe. The mind scatters with pearls, the body trembles with goosebumps, and poetic thoughts of divinity awaken. A subtle sweetness fills communal prayers, untouched by the social atmosphere.

The traditional language of Travancore was Tamil. Moreover, the language of many lower sections was something else entirely, not Malayalam. When choosing to teach a new language, English would have been the most desirable option by far.

Last edited by VED on Sat May 24, 2025 5:56 pm, edited 1 time in total.

7. The nuisance that are caste names

There is much to say about the social, administrative, and other aspects of Travancore, but I do not intend to delve into them now. However, I feel it is worth mentioning a few social conditions.

From around 1800 onwards, it seems the rulers of Travancore generally desired to address the social issues within the kingdom. Yet, they were unable to effect significant change in societal attitudes, as they could not alter the aversion and repulsion created by linguistic codes.

In British-India, there was no legal restriction on any community using a palanquin as a mode of transport. In Travancore, however, this vehicle had long been reserved for the higher sections of the population. In earlier times, this was not an issue. But as various communities across the kingdom began to prosper economically and maintain commercial ties with neighbouring British-India, tensions arose.

A wealthy Shanar merchant from Tirunelveli in the Madras Presidency used a palanquin for travel while in Travancore. Lower-level government officials apprehended him and imposed a heavy fine, likely using derogatory terms like enthadi and nee.

The Madras government may have intervened, as the Diwan stepped in and refunded the fine. Soon after, a government proclamation declared that anyone could use a palanquin. However, oil pressers and communities below them were still not permitted to do so. The oil pressers resolved to challenge this restriction. In 1874, they used a palanquin in a wedding procession through a main street in Trivandrum. The lower sections were growing defiant, likely influenced by the proximity of British-India.

The Shudras (Nairs), witnessing this defiance, portrayed it as a major issue and lodged a complaint with the magistrate. The magistrate fined the offenders for breaching caste boundaries. However, when the case reached a higher court, the ruling changed: using a vehicle peacefully on a public road was deemed lawful. This verdict was unthinkable for the Shudras.

Society’s discipline was being upended. If lower ranks in the military were allowed to behave so defiantly, officers would become irrelevant. This is how matters were unfolding.

The royal family faced no significant threat, as their security and sustenance came from the English administration in British-India. Without this, some powerful entity from Ambalapuzha, Attingal, or Changanassery might have attacked and seized the kingdom.

The royal family did not overly rely on the support of Travancore’s higher sections, whose loyalty and affection were notoriously fickle and unpredictable.

In Kottar, Nagercoil, oil pressers replicated this defiance with palanquins and were fined. The higher court overturned the fine. Subsequently, potters in Kottar displayed similar audacity on the streets. A Brahmin judge in the lower court imposed a fine, citing the proximity of Vellala homes to the street.

Vegetable vendors then followed suit with similar defiance. When confronted by the Vellalas on the street, they paid a fine of 200 rupees and offered other tributes, acknowledging their subservience.

While Rev. Samuel Mateer recounts these events, he shows no awareness of how such behaviour by these communities altered linguistic codes. He expresses no understanding of the menacing and fear-inducing forces lurking in the background.

In 1875, Maharaja Ayilyam Thirunal permitted the removal of caste names from government records for lower sections who converted to Christianity. This was a significant step for them. No matter how refined or dignified an individual might be, if their lower-caste designation remained indelible in their name, linguistic codes would degrade them in public discourse, trampling their dignity.

For lower-caste individuals who gained social freedoms without converting to Christianity, this issue persisted and continues to haunt them today. Their only recourse has been reservation in government jobs, secured as a right. However, this has only lowered the standard of government employment and its environment. The English administration in Tellicherry had shown, at least for a time, that this was not the path to mental elevation. Today, this lesson is forgotten, and people rush through the shortcut of reservation to achieve social advancement and suppress others.

In the Madras and Bombay Presidencies, the precedent of removing former caste names for lower-caste converts to Christianity served as an example for the royal decree. One might think a lower-caste Christian could now walk public roads without significant issues.

However, concealing such a designation could socially complicate matters. For instance, if a soldier in the military removed the title of sepoy and appeared indistinguishable from an officer, many officers might be uncertain whether to address them as thoo, tum, or aap. This could also foster a sense of defiance among some soldiers, perceived as insolence.

A similar issue is emerging in the Kerala Police, it seems worth noting. In India, ordinary police are defined in Hindi as sepoy, a term possibly linked to the English word sepoy. In local feudal languages, hierarchical codes place the sepoy policeman at the lowest rung within the police department.

However, the hierarchical codes in the police differ from those in the military. Multiple complex hierarchical codes extend upwards, downwards, and in various directions within the police. Documenting this complexity precisely would require a separate opportunity, which this is not.

Many Travancore government officials resisted removing caste names from the records of converted lower-caste individuals. In the 1881 Census, many such individuals were still recorded under their old caste names.

In Nagercoil, Christians refusing to disclose their former caste names in court caused a significant issue. The court threatened to charge them with contempt, and they relented under pressure.

From around 1800 onwards, it seems the rulers of Travancore generally desired to address the social issues within the kingdom. Yet, they were unable to effect significant change in societal attitudes, as they could not alter the aversion and repulsion created by linguistic codes.

In British-India, there was no legal restriction on any community using a palanquin as a mode of transport. In Travancore, however, this vehicle had long been reserved for the higher sections of the population. In earlier times, this was not an issue. But as various communities across the kingdom began to prosper economically and maintain commercial ties with neighbouring British-India, tensions arose.

A wealthy Shanar merchant from Tirunelveli in the Madras Presidency used a palanquin for travel while in Travancore. Lower-level government officials apprehended him and imposed a heavy fine, likely using derogatory terms like enthadi and nee.

The Madras government may have intervened, as the Diwan stepped in and refunded the fine. Soon after, a government proclamation declared that anyone could use a palanquin. However, oil pressers and communities below them were still not permitted to do so. The oil pressers resolved to challenge this restriction. In 1874, they used a palanquin in a wedding procession through a main street in Trivandrum. The lower sections were growing defiant, likely influenced by the proximity of British-India.

The Shudras (Nairs), witnessing this defiance, portrayed it as a major issue and lodged a complaint with the magistrate. The magistrate fined the offenders for breaching caste boundaries. However, when the case reached a higher court, the ruling changed: using a vehicle peacefully on a public road was deemed lawful. This verdict was unthinkable for the Shudras.

Society’s discipline was being upended. If lower ranks in the military were allowed to behave so defiantly, officers would become irrelevant. This is how matters were unfolding.

The royal family faced no significant threat, as their security and sustenance came from the English administration in British-India. Without this, some powerful entity from Ambalapuzha, Attingal, or Changanassery might have attacked and seized the kingdom.

The royal family did not overly rely on the support of Travancore’s higher sections, whose loyalty and affection were notoriously fickle and unpredictable.

In Kottar, Nagercoil, oil pressers replicated this defiance with palanquins and were fined. The higher court overturned the fine. Subsequently, potters in Kottar displayed similar audacity on the streets. A Brahmin judge in the lower court imposed a fine, citing the proximity of Vellala homes to the street.

Vegetable vendors then followed suit with similar defiance. When confronted by the Vellalas on the street, they paid a fine of 200 rupees and offered other tributes, acknowledging their subservience.

While Rev. Samuel Mateer recounts these events, he shows no awareness of how such behaviour by these communities altered linguistic codes. He expresses no understanding of the menacing and fear-inducing forces lurking in the background.

In 1875, Maharaja Ayilyam Thirunal permitted the removal of caste names from government records for lower sections who converted to Christianity. This was a significant step for them. No matter how refined or dignified an individual might be, if their lower-caste designation remained indelible in their name, linguistic codes would degrade them in public discourse, trampling their dignity.

For lower-caste individuals who gained social freedoms without converting to Christianity, this issue persisted and continues to haunt them today. Their only recourse has been reservation in government jobs, secured as a right. However, this has only lowered the standard of government employment and its environment. The English administration in Tellicherry had shown, at least for a time, that this was not the path to mental elevation. Today, this lesson is forgotten, and people rush through the shortcut of reservation to achieve social advancement and suppress others.

In the Madras and Bombay Presidencies, the precedent of removing former caste names for lower-caste converts to Christianity served as an example for the royal decree. One might think a lower-caste Christian could now walk public roads without significant issues.

However, concealing such a designation could socially complicate matters. For instance, if a soldier in the military removed the title of sepoy and appeared indistinguishable from an officer, many officers might be uncertain whether to address them as thoo, tum, or aap. This could also foster a sense of defiance among some soldiers, perceived as insolence.