7. If one falls into the deep chasms of language codes

7. If one falls into the deep chasms of language codes

Written by VED from VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

Previous page - Next page

[/size]

[/size]

1. The system of directly approaching a government officer:

2. When one Indian is given authority over another Indian

3. If a person uses bestial languages, he or she becomes bestial

4. The Linguistic Expressions of Animals

5. The Distinctive Influence of English in Tellicherry

6. If one were to venture out without elaborate adornments, attendants, or bodily ornaments

7. Like Living on the Streets

8. The Elusive Links of Social Equality

9. Smouldering Resentment and Verbal Codes That Diminish Skill

10. Imparting Divinity to the Software of Life

11. Undermining the Social Movement That Upholds

12. The Underside of Feudal Linguistic Supremacy

13. The Plight Within Aristocracy

14. Falling into the Abyss of Language Codes

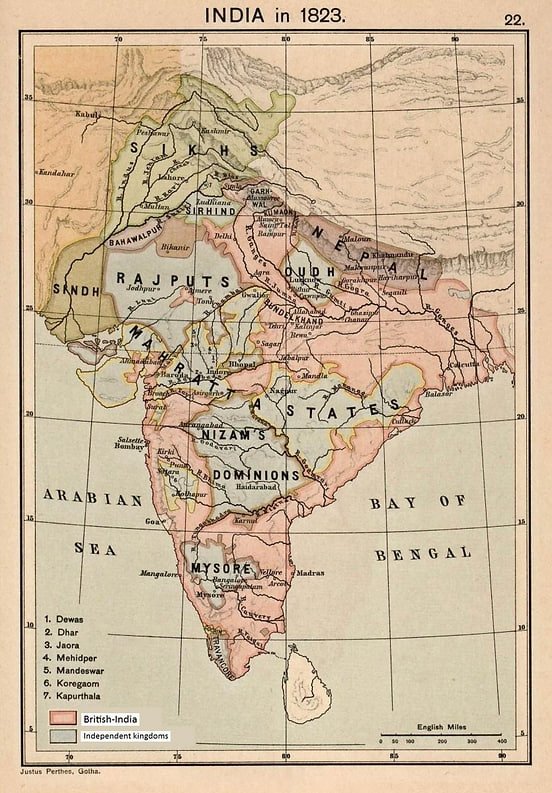

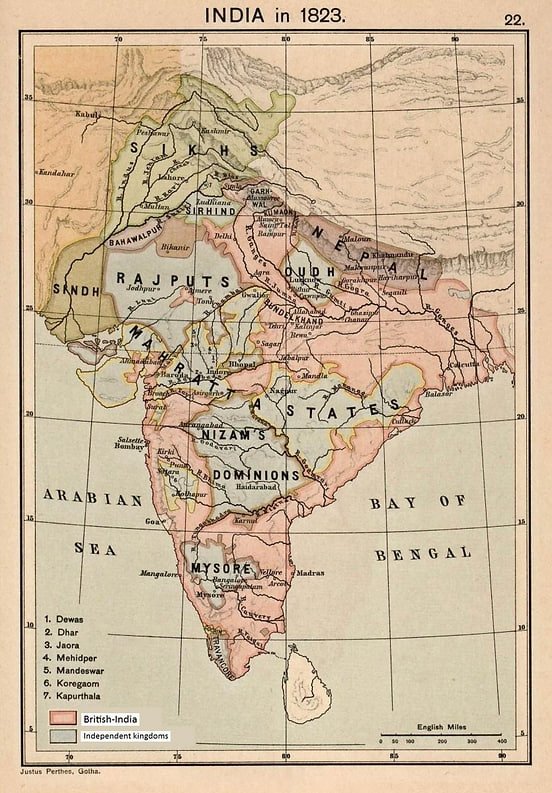

15. Before the English Company Brought Social Light to This Region

16. Sorcery, Black Magic, Massacres, and More

17. Odiyan and Pillathailam

18. The Mechanism of Esoteric Practices

19. The Invisible Software Codes Embedded in Mudras

20. When Trapped in the Hands of Feudal Language Speakers

21. A National History Education That Portrays the Virtuous as Villains

22. The Underbelly of Indian Social Tolerance

23. Life Experiences Through Three Distinct Historical Eras

24. Thiyyas Standing at Opposite Poles

25. The Multiple Personalities Forged by Feudal Languages

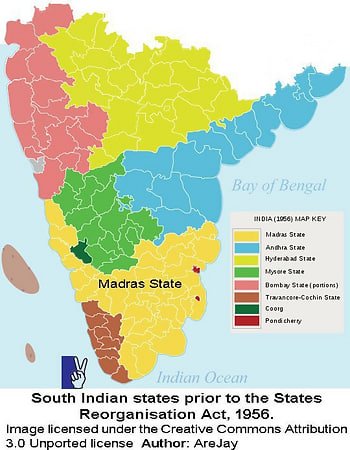

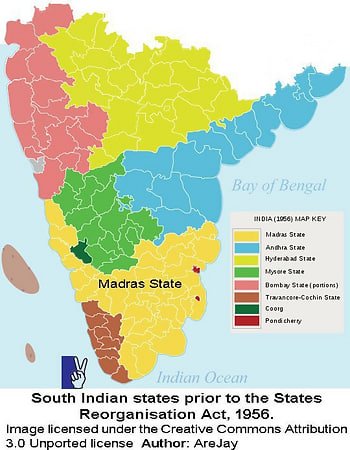

26. Malabar, Cochin, and Travancore

27. Affection and Respect for Queen Victoria

28. Traditions Beyond Imagination

29. When South and North Malabar Were Merged to Form Malabar District

30. The Impossible Mission the English East India Company Had to Undertake

31. The Ups and Downs Within Thiyya Communities

32. When Two Distinct Malabars Were Unified

33. The Concerns of Marumakkathayam Thiyars

34. Lower Communities Beginning to Envision Social Freedom, Once Again Under the Yoke of Social Elites

35. The Misguided Intellectuals of England

36. A Name Not of Hindu Origin

37. On Non-Hindus Becoming Hindus

38. Faded from Memory

39. Changes Among the Marumakkathayam Thiyars in Tellicherry

40. New Leaders Set Out to Rechain the Lower Castes Who Slipped Free

41. Those Proclaiming Themselves Leaders of the Subcontinent

42. The True Motivation Behind the Freedom Struggle

43. Those Scheming to Become Self-Proclaimed Leaders

44.The Linguistic Heritage at the Cradle of Malayalam

45. The Rise of a New Man in This Peninsula

46. Academic Follies

47. On Malabar Becoming British Malabar

48. Those Complicit in Writing False History

49. Who Truly Brought Social Reform to This Land

50. Tribespeople and Semi-Civilised Urban Dwellers

Previous page - Next page

Vol 1 to Vol 3 have been translated into English by me directly.

From Vol 4 onward, the translation has been done by a translation software. So there can be slight errors in the text.

It was slightly difficult to make the translation software to understand that in Indian languages, there are hierarchy of words everywhere.

From Vol 4 onward, the translation has been done by a translation software. So there can be slight errors in the text.

It was slightly difficult to make the translation software to understand that in Indian languages, there are hierarchy of words everywhere.

[/size]

[/size]1. The system of directly approaching a government officer:

2. When one Indian is given authority over another Indian

3. If a person uses bestial languages, he or she becomes bestial

4. The Linguistic Expressions of Animals

5. The Distinctive Influence of English in Tellicherry

6. If one were to venture out without elaborate adornments, attendants, or bodily ornaments

7. Like Living on the Streets

8. The Elusive Links of Social Equality

9. Smouldering Resentment and Verbal Codes That Diminish Skill

10. Imparting Divinity to the Software of Life

11. Undermining the Social Movement That Upholds

12. The Underside of Feudal Linguistic Supremacy

13. The Plight Within Aristocracy

14. Falling into the Abyss of Language Codes

15. Before the English Company Brought Social Light to This Region

16. Sorcery, Black Magic, Massacres, and More

17. Odiyan and Pillathailam

18. The Mechanism of Esoteric Practices

19. The Invisible Software Codes Embedded in Mudras

20. When Trapped in the Hands of Feudal Language Speakers

21. A National History Education That Portrays the Virtuous as Villains

22. The Underbelly of Indian Social Tolerance

23. Life Experiences Through Three Distinct Historical Eras

24. Thiyyas Standing at Opposite Poles

25. The Multiple Personalities Forged by Feudal Languages

26. Malabar, Cochin, and Travancore

27. Affection and Respect for Queen Victoria

28. Traditions Beyond Imagination

29. When South and North Malabar Were Merged to Form Malabar District

30. The Impossible Mission the English East India Company Had to Undertake

31. The Ups and Downs Within Thiyya Communities

32. When Two Distinct Malabars Were Unified

33. The Concerns of Marumakkathayam Thiyars

34. Lower Communities Beginning to Envision Social Freedom, Once Again Under the Yoke of Social Elites

35. The Misguided Intellectuals of England

36. A Name Not of Hindu Origin

37. On Non-Hindus Becoming Hindus

38. Faded from Memory

39. Changes Among the Marumakkathayam Thiyars in Tellicherry

40. New Leaders Set Out to Rechain the Lower Castes Who Slipped Free

41. Those Proclaiming Themselves Leaders of the Subcontinent

42. The True Motivation Behind the Freedom Struggle

43. Those Scheming to Become Self-Proclaimed Leaders

44.The Linguistic Heritage at the Cradle of Malayalam

45. The Rise of a New Man in This Peninsula

46. Academic Follies

47. On Malabar Becoming British Malabar

48. Those Complicit in Writing False History

49. Who Truly Brought Social Reform to This Land

50. Tribespeople and Semi-Civilised Urban Dwellers

Last edited by VED on Sat Aug 09, 2025 12:37 pm, edited 13 times in total.

1. The system of directly approaching a government officer:

The issue with the societal perspective on an ordinary person going to meet an officer directly for some purpose is this: unless an individual has a hierarchy of people beneath them, the sense of respect—devotion and reverence—will not take root in the mind of the person approaching.

In Travancore, the address "Saar" to some extent ensures and reinforces respect. However, since the term "Saar" is equally claimed by the peon, the clerk, and the officer, the person approaching directly might feel that the officer is just another "Saar" like the others. For this reason, in the Travancore administrative system, it was not particularly favoured for an ordinary citizen to directly approach an officer.

This is where the significant, yet often undocumented, difference lies in the formal history of British Malabar: the requirement to directly meet the officer, without needing to deal with subordinates, marks a profound distinction.

What sustained this practice was the English mindset of directly recruited officers. It must be noted that, while it is true these officers typically communicated in English, most of them lived within the local linguistic and social environment. Consequently, their personalities likely exhibited a certain ambivalence, and their societal outlook reflected a dichotomy. I won’t delve into the intricacies of this matter now, but I may explore it later.

In Travancore, the peon, clerk, and officer seemed to operate much like the Indian administrative system today. In terms of linguistic knowledge, societal outlook, behaviour, interpersonal language codes, and other aspects, these three groups were largely of the same kind. In every way, government employees, as overseers, viewed the common people as their subordinates.

In contrast, in the English administrative system of Malabar, directly recruited officers held an English egalitarian societal outlook, while their subordinates operated solely within a rigid, hierarchical linguistic framework. However, it can be said that the public had little need to interact with the latter group.

Nevertheless, one might encounter individuals with strong English proficiency at various levels. For instance, in Malabar’s government system, you might find clerks with excellent English knowledge. But this makes no difference. They remain merely a particle within the blanket that covers and binds all clerks and others together.

They can only behave and function like other clerks.

Many years ago, a commissioned officer in the Indian Army shared a similar insight. Some individuals from the northeastern states, joining as ordinary soldiers, might have strong English proficiency. However, officers do not allow them to use English. The reason is that, in Hindi, they are addressed as "tu" (lowest you) and referred to as "uss" (lowest he / him). If they were allowed to use English, they would rise to the level of "You" and "He."

If that were to happen, the officer, residing in the realm of word-codes, would experience a loss of power. In feudal languages, an Indian Army officer is like Lord Shiva, performing the cosmic dance of destruction behind a divine veil, while the ordinary soldier is like Apasmara, eternally crushed beneath Shiva’s foot.

However, reality does not conform to this metaphor. Word-codes cannot touch Shiva, but they can touch the officer. The officer is not suppressing Apasmara but rather the local individual who joined the army seeking government employment. This distinction embodies a subtle, disruptive secret.

2. When one Indian is given authority over another Indian

It does not seem that today’s army officers would allow their subordinates to speak English with them. I recall personally observing that in Malabar, officers would, as far as possible, provide opportunities for their subordinates to speak English.

I am attempting to briefly highlight how distinct the administrative system in old Malabar was from that in Travancore. However, before doing so, there is something else I must mention.

I base these writings on several things: observations, experiences, and things I have heard in my own life. Additionally, I have read works such as the Travancore State Manual, Native Life in Travancore, and Malabar Manual multiple times, analysing them from the perspective of my own insights.

Beyond this, I have also drawn upon knowledge about English linguistic culture—things even the English themselves may not fully understand—and used this for these writings.

I firmly believe that English colonialism should not, under any circumstances, be equated with continental European colonialism. In reality, continental European colonialism stood in complete opposition to English colonialism in every way. Yet, many foolish formal histories today treat the two as the same.

That said, I must acknowledge certain weaknesses in my insights and claims. While my personal experiences, observations, and hearsay are extensive, there are countless matters beyond these limits.

For example, I do not know anyone from that era to ask about the experiences of the public at police stations in British Malabar.

However, when compared to Travancore, it seems that the police in Malabar were likely less harsh back then. What comes to mind on this matter are one or two things.

One is that I recall reading something written by Mr. K. Venu, a former Naxal activist, about his experiences in jail. Comparing the behaviour of the Malabar and Travancore police, Mr. K. Venu noted that the Travancore police were relatively brutal, while the Malabar police were comparatively milder. He attributed this to the fact that the Malabar police emerged from English rule.

Another point to mention is a quotation from this very work.

QUOTE from Vol 3 of this book: I had the opportunity to read a record by an English IP Officer who served in this subcontinent, which stated:

QUOTE: Under no circumstances should one Indian be given authority over other Indians. If given, it is certain to be misused. END OF QUOTE

Another English IP Officer recorded with astonishment that, despite strict warnings not to mistreat individuals brought to the police station for questioning, if the English officers stepped away even briefly, the police would slap the person brought in and engage in other such acts.

The officer was baffled as to why the police behaved this way.

However, whether the English officer was aware that those addressed as "Saar," "Ningal - higher you)," "Adheham - highest he / him," or "Avar -Highest she / her" would not be slapped, while those addressed as "nee" (lowest you), "avan" (lowest he), or "aval" (lowest she) would face such treatment, is unknown. END OF QUOTE from Vol 3 of this book

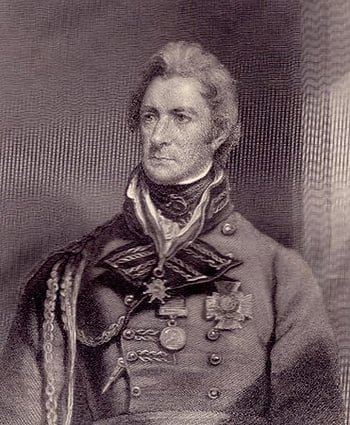

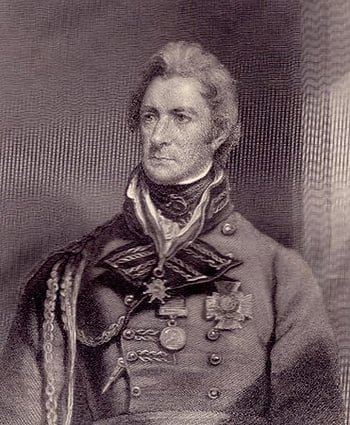

One point to highlight here is that for the English (not the Irish, Scottish, Germans, or others), understanding and learning the languages of this subcontinent was extremely difficult. It is known that Robert Clive, who laid the foundation for English rule in this subcontinent and led its administration for many years, made no effort to learn these languages.

Languages of the southern peninsula, like Tamil, were far more challenging than Hindi.

In such a region, English ICS/IP Officers serving as administrators likely perceived the communication, mindset, and social dynamics of their subordinates and the public in a manner akin to a human trying to understand such matters in animals.

I am attempting to briefly highlight how distinct the administrative system in old Malabar was from that in Travancore. However, before doing so, there is something else I must mention.

I base these writings on several things: observations, experiences, and things I have heard in my own life. Additionally, I have read works such as the Travancore State Manual, Native Life in Travancore, and Malabar Manual multiple times, analysing them from the perspective of my own insights.

Beyond this, I have also drawn upon knowledge about English linguistic culture—things even the English themselves may not fully understand—and used this for these writings.

I firmly believe that English colonialism should not, under any circumstances, be equated with continental European colonialism. In reality, continental European colonialism stood in complete opposition to English colonialism in every way. Yet, many foolish formal histories today treat the two as the same.

That said, I must acknowledge certain weaknesses in my insights and claims. While my personal experiences, observations, and hearsay are extensive, there are countless matters beyond these limits.

For example, I do not know anyone from that era to ask about the experiences of the public at police stations in British Malabar.

However, when compared to Travancore, it seems that the police in Malabar were likely less harsh back then. What comes to mind on this matter are one or two things.

One is that I recall reading something written by Mr. K. Venu, a former Naxal activist, about his experiences in jail. Comparing the behaviour of the Malabar and Travancore police, Mr. K. Venu noted that the Travancore police were relatively brutal, while the Malabar police were comparatively milder. He attributed this to the fact that the Malabar police emerged from English rule.

Another point to mention is a quotation from this very work.

QUOTE from Vol 3 of this book: I had the opportunity to read a record by an English IP Officer who served in this subcontinent, which stated:

QUOTE: Under no circumstances should one Indian be given authority over other Indians. If given, it is certain to be misused. END OF QUOTE

Another English IP Officer recorded with astonishment that, despite strict warnings not to mistreat individuals brought to the police station for questioning, if the English officers stepped away even briefly, the police would slap the person brought in and engage in other such acts.

The officer was baffled as to why the police behaved this way.

However, whether the English officer was aware that those addressed as "Saar," "Ningal - higher you)," "Adheham - highest he / him," or "Avar -Highest she / her" would not be slapped, while those addressed as "nee" (lowest you), "avan" (lowest he), or "aval" (lowest she) would face such treatment, is unknown. END OF QUOTE from Vol 3 of this book

One point to highlight here is that for the English (not the Irish, Scottish, Germans, or others), understanding and learning the languages of this subcontinent was extremely difficult. It is known that Robert Clive, who laid the foundation for English rule in this subcontinent and led its administration for many years, made no effort to learn these languages.

Languages of the southern peninsula, like Tamil, were far more challenging than Hindi.

In such a region, English ICS/IP Officers serving as administrators likely perceived the communication, mindset, and social dynamics of their subordinates and the public in a manner akin to a human trying to understand such matters in animals.

3. If a person uses bestial languages, he or she becomes bestial

Many thoughts come to mind about how English people dealt with the languages of this peninsula. However, if I were to note them all here, the narrative would stray into side stories. Still, I feel compelled to share one story, as I’m unsure when another fitting opportunity might arise.

During the time of English rule in the Madras Presidency, the region was historically the land of the Cholas and Pandyas. In many parts, various plantations were established during English rule—some owned by the British, others by continental Europeans, and some by local landlord families.

For centuries, many lower-caste individuals lived as slaves under landlord families. In droves, they escaped and joined the plantations owned by the English, where wages were comparatively higher and the social environment relatively milder.

In English-owned plantations (tea, cardamom, coffee, etc.), young men from England were appointed as managers. Some companies had a rule requiring these managers to know Tamil.

Thus, these young Englishmen had to learn Tamil and pass a Tamil exam, which, for them, was a tremendous ordeal. The peculiarities of Tamil words—when viewed from an English perspective—their richness, twists, potency, insults, praises, emotions, and arrogance, were utterly distasteful and unbearable for these young Englishmen. This was because English, with its flat codes, was entirely different.

But how could they communicate with the workers without knowing Tamil? They devised a brilliant solution: instead of learning Tamil, they would teach the plantation workers English. Many locals had already proven that English could be learned quickly.

They proposed this idea to the company’s higher-ups. While the idea was acceptable to the company leadership, the local overseers directly above the plantation workers fiercely opposed it. The reason was that these young Englishmen, in their ignorance, had proposed a revolutionary idea that would upend the social structure.

In Tamil, words like "nee" (lowest you), "unakku," "neenge," "ennada thambi," "avan" (lowest he), "aval" (lowest she), "aale paathu pesunge (speak after assessing the person)," "thevar, (social divinity)" "anna (honoured social elder brother)," "periyanna, (great personage)O" and countless others, along with verb forms that convey respect or contempt, construct a social code of extreme subservience, submission, humility, restraint, servitude, and lack of self-respect, as well as boundless dominance. These codes, etched into the social structure like iron scripts for ages, would erode and vanish with the spread of English.

The codes of the languages a being uses are reflected in its character and traits. If humans learn bestial languages, they too become bestial.

For example, if a human learns the language of dogs, there’s no need to explicitly state that they would bark on the streets. If they learn the language of foxes or wolves, on moonlit nights bathed in silver, humans would gaze at the crescent moon and howl, dancing in packs.

4. The Linguistic Expressions of Animals

Since I mentioned dogs, I thought I’d add this as well. It seems the word "dog" is often used as an insult in many places. In English, the word "bitch" is frequently used as a derogatory term, though it means a female dog. (I have a feeling the word "Naya" is a Malabari term; in Malayalam, the word is "patti.")

Generally speaking, in English societies, dogs—especially household pets—are often valued as family members in many homes.

However, in feudal language regions, dogs are mostly viewed with contempt. In English, dogs are often referred to as "he" or "she".

In contrast, in the feudal languages of this peninsula, dogs are referred to as "it" or, at times, "avan" (lowest he) or "aval" (lowest she). They are also called "eda" or "vada", both perjorative usages.

When the English East India Company arrived in this peninsula centuries ago, they encountered communities kept at a very low status by higher groups, treated as mere animals, half-humans, or half-beasts. Individuals in these communities were addressed by the higher classes as "avan" (lowest he), "aval" (lowest she), or "it." To put it plainly, it seems that when a socially high-ranking person died, the word "marichu" was used, but when a lower-caste person died, the word "chathu" (lower class death) was used.

About thirty-five years ago, I recall visiting Deverkovil. The area was mostly deserted. At night, packs of foxes would gather in the pitch darkness around the house, performing all sorts of acrobatics, responding to some invisible signals, rhythms, or rhymes, standing and sitting together, howling in unison. These howls, piercing the darkness of the night in all directions, instilled both fear and, when listened to, a rare, enchanting allure in the mind.

One noon, while walking near the woodshed behind the house, I witnessed a peculiar scene. A dog was sitting in the woodshed, as if on a royal throne. Four or five other dogs stood before it, front legs extended, bowing in extreme subservience, displaying loyalty.

Hearing human movement, the dogs dispersed and slowly left the area.

It seems street dogs often have distinct packs, a dominant dog, and other hierarchies. Moreover, there appear to be various forms of aristocracy, hierarchies, leadership, and struggles for dominance among them.

Furthermore, if a dog enters a pack without showing clear subservience to the dominant dog, it faces an experience akin to an ordinary citizen entering a government office in a feudal language region without a subservient attitude. The other dogs will attack and try to tear it apart.

I don’t know how dogs communicate with each other. Dogs in England might be influenced by the flat codes of English in their communication, while dogs in feudal language regions may be shaped by feudal language codes.

It’s well-known that animals have hierarchies and individuals who hold higher positions. However, it seems English observers were unaware that these are underpinned by clear hierarchical language codes. Nor does it seem others explained this to them.

In about three hundred years, I believe humans will directly communicate with some animals. Though this may seem impossible today, many things once thought impossible have come to pass.

In this peninsula, it was once unimaginable that lower-caste individuals would live as ordinary citizens in civilized societies. English colonial rule broke this barrier wherever it spread. In Africa, many communities oppressed by local social elites rose to great social heights. The practice of cannibalism, a bestial culture, was largely eradicated.

A cannibal was once a being too repulsive for other humans to approach. Today, even such beings have joined human society.

I’ll leave this topic here and return to the main thread of the writing.

Last edited by VED on Sat May 03, 2025 7:34 pm, edited 1 time in total.

5. The Distinctive Influence of English in Tellicherry

When discussing the Malabar administrative system, I must include observations, inquiries, and hearsay gathered in the presence of my mother.

She (my mother) was born and educated in Tellicherry, a member of the matrilineal Thiyya community or religion. English governance first took root in Malabar in Tellicherry. Later, when Malabar District was formed, the administrative centre shifted to Calicut, but Tellicherry remained a subdivisional centre.

It seems Tellicherry experienced the greatest influence of the English social environment in Malabar. However, the arrival and presence of various Christian movements may have caused some confusion among locals about what constituted the true English movement.

This is because there was a clear distinction between the English movement and the various Christian movements that migrated from Travancore.

Since the English were also a type of Christian, and others lacked knowledge about the differences between various Christian groups, the English movement may have been perceived as a form of Christian movement.

Moreover, it appears that local Christian movements often misled the English who came from England. Additionally, Irish and Scottish individuals from Britain, upon arriving in this region, sometimes fell under the influence of these local Christian movements.

This background requires much elaboration, but I won’t delve into it now.

The reality is that the light of the English social environment in Tellicherry pushed the dark shadows of various feudal attitudes in the local social environment into the dim corners of social boundaries.

It seems the most profound benefit of this was reaped by the matrilineal Thiyya community in Tellicherry. A small group within this community quickly developed a deep intellectual affinity with high-quality English and English classical literature.

Just a few miles away, a large Thiyya community existed, where Thiyya women (Thiyyathi) lived with their chests half-covered by a mere cloth, using the same cloth as a skirt, and Thiyya men (Thiyyan) wore palm-leaf hats and cloths as loincloths. Many of these women worked in paddy fields, transplanting seedlings, sowing seeds, and harvesting crops for generations to earn a living. In Malabari language codes, higher social groups addressed them as "inhi" (lowest you), "ale," "ane," "chekkan" (lowest boy), "pennu" (lowest girl), "olu" (lowest she), "oan" (lowest he), "aittingal (lowest them)," "eda," "edi," and similar terms. They lacked the social codes to sit on chairs.

While working in the paddy fields, they sang Thacholi songs and other northern ballads, now known as tales of their heroic ancestors, to entertain themselves.

At the same time, landlords known as "Thiyyar" viewed them with great disdain.

Meanwhile, in Tellicherry, Thiyya women began wearing saris and blouses, and Thiyya men started wearing dhotis and shirts. This was likely possible due to the weakening of the social dominance of Hindus (Brahmin adherents).

At the same time, young "Thiyyar" educated in English schools in Tellicherry began wearing trousers, then understood as English attire. Some even wore hats. Some women wore sleeveless blouses, outshining in fashion both women from other areas who didn’t cover their chests and those who wore regular blouses.

Many spoke excellent English.

A general perception spread in other parts of North Malabar that the "Thiyyar" of Tellicherry were refined. This refinement and elevation lacked any traditional foundation. It was merely a blossoming and sprouting fostered by the English movement and its enduring light.

This was experienced in various ways by my mother and her family. During her time working in Travancore, I heard my mother say to others, without hesitation and with a sense of superiority, “We are Thiyyas from Tellicherry.”

Back then, I didn’t understand the meaning of “Thiyyas from Tellicherry.” Moreover, I had a vague notion that “Thiyyas” were a kind of elevated religious group. My understanding of social realities in childhood was very limited.

To truly delve into the inner workings of Malabar’s English administrative system, the social context must first be explained effectively. Otherwise, only hollow historical information will take root in the mind.

6. If one were to venture out without elaborate adornments, attendants, or bodily ornaments

I have already mentioned that the sheen observed among a small minority of the matrilineal Thiyyar believers in Tellicherry lacked any traditional foundation. Before this narrative progresses, I shall, for the time being, exclude Muslims and Christians from the discussion and address the social structure of the others.

It seems fitting to briefly mention the purported wealth and nobility associated with the Hindus at the highest echelons (Brahmin believers), the temple-dwelling Ambalavasis closely aligned with them, and, below these two groups, the Nayars, who served as overseers of the landlords’ properties and performed roles that could be defined as martial.

Although it is generally said that Hindu temples belong to Brahmins, it appears that some of the grand temples were constructed by foreign rulers who had conquered the land. The precise motivations behind this are unclear due to a lack of complete information.

However, I can suggest a couple of possibilities. One might be that these temples were built to appease local deities. Another could be to please Brahmin deities (Hindu gods) or, alternatively, to win over the Brahmins themselves. Gaining Brahmin approval, or having Brahmins certify that a foreign ruler is a Kshatriya, could facilitate social acceptance and order. It is akin to introducing oneself in the locality as an IAS officer—police officers would come and salute.

Beyond all this, it might also have been to seek divine forgiveness for atrocities committed in war and to find some mental peace from the associated distress.

Upon close examination of history, subtle indications corroborate all the aforementioned points. In other words, these are not merely figments of my imagination.

Despite all this, it does not seem that Brahmins ever had the social security to move freely within their own communities.

It is much like what is said about IPS officers today. If they venture out in ordinary attire—mundu and shirt—into unfamiliar parts of town without their uniform, no one would show them respect. At times, even a constable might give them a jolt. The women in the households of IPS officers face a similar issue. A familiar constable might call out, “Enthada,” and not hesitate to say, “Enthadi,” either. Female constables, in particular, seem to have a special privilege in this regard—they would not let any woman in their custody go without being stung by such words.

(Enthada / enthadi words are hundred times worse that the nigger word. However, it depends on who is using the word on whom.)

However, this is not a significant issue in this land today. The reason is that there exists a robust police system that strongly enforces the value of an IPS officer’s official status. When needed, displaying that status suffices.

One could say that Brahmins, too, have a similar status symbol—their sacred thread. It is not possible here to delve into the ritualistic and sanctified aspects associated with the sacred thread. However, it seems that, beyond its spiritual significance, the sacred thread also carries a temporal connotation.

In the past, displaying the sacred thread might have been akin to an IPS officer showcasing their status. Ambalavasis, Nayars, and the subordinate masses loyal to them would offer respect and consideration.

However, not everyone would comply, especially in the case of Brahmin women. If they ventured out without elaborate adornments, attendants, or bodily ornaments, it would not take long for them to be reduced from “Oru” to “Olu” in the eyes of others. Furthermore, men unwilling to acknowledge their superiority might openly tarnish them with irreverent, malicious, defiling, vulgar, or lascivious looks and words.

If a subordinate individual, devoid of subservience, were to cast a lustful glance with overt vulgarity, the person deserving respect would be utterly diminished.

It seems that, in earlier times, English-speaking people were entirely unaware of this dynamic. They had no knowledge whatsoever that a lustful glance, devoid of vulgarity but embedded in coded words, could reduce someone from “Oru” to “Olu.” However, today, in English-speaking nations, they are fleeing en masse from areas where feudal-language communities reside. It does not appear that they can clearly articulate what is socially degrading them.

It seems that Brahmins often lived in clusters in agraharas in various regions. There were others who lived differently. While it is true that they enjoyed social superiority, it also feels as though this very superiority acted as a shackle and chain.

Moreover, it appears that among these groups, many castes faced various restrictions related to marital life.

Despite all this, some among them were appointed as envoys by petty kings and others. The reason being that, ordinarily, no one would attack them on the road, as killing a Brahmin was considered a grave sin. Furthermore, it is observed that in the regions they travelled, there were feeding houses and other facilities linked to many grand temples, where they could stay and eat for free.

It seems that even young individuals among them were not addressed as “Inhi” by lower-caste people. However, it also appears that they could address or refer to those who acknowledged their superiority using such terms.

The feudal-language social atmosphere is not particularly enjoyable. It is akin to working in government offices. Even if one works daily in an utterly dull environment, the subservience extracted from ordinary people makes the job highly gratifying. Some among them might feel that this is the most heavenly social atmosphere attainable in this world—until they encounter a pristine English social environment.

Last edited by VED on Fri May 02, 2025 3:14 pm, edited 1 time in total.

7. Like Living on the Streets

It should be inferred that, over generations, communities that hold a high position in language codes develop a mental and physical superiority. One could say this is inscribed in the supernatural software codes that shape their physical structure. In terms of current scientific knowledge, it might be said that these codes are encoded in their genes and DNA. However, this is merely a very simplistic and superficial assumption about reality. It is unclear whether medical scholars have substantial knowledge about the software codes operating behind genes. The primary reason for this is that most of them lack a deep understanding of software.

Among Brahmins, who have held high social positions for generations, the influence of transformations in these software codes might have been clearly observable. However, it can be assumed that their superiority was achieved solely by suppressing others through verbal codes. This simply means that the social atmosphere in which they stand at the top is rooted in feudal language. They maintain their position using verbal codes such as “Inhi,” “Inakku,” “Inre,” “Oan,” “Olu,” “Oanre,” “Olude,” “Aittingal,” “Aittingade,” or merely a name. This is an experience that cannot be replicated in English. It is akin to living on the streets. When isolated individuals living on the streets are defined by such words by social overlords or others, they are often left in a state with no protection whatsoever.

This social atmosphere can also be experienced in conditions such as living in a small house, having limited financial means, engaging in low-status work, or residing in a thatched hut.

Below the Brahmins, there is a hierarchy of communities: Ambalavasis, Nayars, Thiyyars, and then, step by step, lower castes further down. The communities below the Nayars are like ordinary people caught in the hands of today’s Indian police constables. Even among ordinary people, there are further hierarchical layers downward.

Only a small percentage of the matrilineal Thiyyars in Thalassery managed to escape this condition. By gaining proximity to English movements and mastering the English language, the communities that had oppressed them for generations began to fade away. Nevertheless, these Thiyyars were still speakers of the Malabari language. Consequently, they continued to oppress both the communities that had been subjugated under them for generations and those among the Thiyyars who were economically disadvantaged.

Among the matrilineal Thiyyars who attained this elevated mental state, another sentiment later emerged. It can be assumed that, in earlier times, they were not granted entry into Brahmin households. This is because the distances that each lower caste had to maintain from Brahmins and others were very clearly defined. The “Thiyya-pad” was the distance Thiyyars had to maintain, which was much shorter than the “Cheruma-pad,” as the Cherumars were a far lower community.

A point to briefly note here is that these distances are closely tied to feudal-language codes. The reality is that those at the lower rungs have the ability to transmit and replicate negative codes through actions like looking or touching. In fact, touching is not even necessary. If a person of lower status merely calls out a name, it can trigger profound changes in the physical structure, personality, and social dignity of the person of higher status.

For example, a constable need not even call an IPS officer “Inhi”; merely referring to her as “Olu” within her earshot is enough to induce a behavioural transformation akin to schizophrenia in her mind.

There is much to say on this matter in greater depth, but that can be addressed later.

8. The Elusive Links of Social Equality

It is necessary to further clarify the use of expressions such as “Inhi,” “Inakku,” “Inre,” “Oan,” “Olu,” “Oanre,” “Olude,” “Aittingal,” “Aittingade” (Malabari words), and merely a name. The use of these words may feel as though it represents profound equality, ideological freedom, and the depth of personal connection.

However, this is a misunderstanding. Whether entering or descending into any society, knowing who can mutually use these verbal codes provides a powerful insight. A person achieves equality only at the level where these words can be used reciprocally. These words do not indicate a general social equality.

In reality, this is an extremely potent form of linguistic coding. The truth is that English-speaking people have no grasp whatsoever of this peculiar reality.

Those who use these words among themselves also employ them towards those considered beneath them. However, those of lower status must never use these words in return. If they do, it results in severe insult, degradation, suppression, demotion, devaluation, and dishonour.

At times, when a person of higher status lacks the capability, support, commanding presence, or an elevated official title to counter such an attack, and someone introduces them with demeaning remarks, provides degrading information, or hints at socially inferior connections, the person of higher status is truly devastated—mentally, socially, and personally. This is because, in such instances, others immediately deploy the aforementioned verbal codes. English-speaking people have no awareness of this phenomenon.

The essence of Brahmin supremacy lies in the existence of multiple communities, layered hierarchically, within a social atmosphere woven by these verbal codes.

Brahmins do not need to exert excessive effort to maintain these layered communities. Each layer suppresses and controls the layers beneath it.

This, too, is a phenomenon absent in English social environments. Even when old English communities organised, they did not develop a mindset that incited mutual betrayal or destruction. One of the secrets behind the historical social strength of the English during the colonial era lies in this.

The strength of Brahmin families’ wealth and nobility does not stem from the belief that their traditions included Vedic texts, mantras, astrology, rituals, or worship practices. Rather, it is because language codes, capable of piercing and subjugating over 90% of the population step-by-step with the sharpness of terms like “Inhi,” “Oan,” “Olu,” and “Aittingal,” are pervasive in society.

Those beneath cannot organise to oppose this, as each individual bows upward while trampling and tearing down those below. This social condition is shaped by language codes, not by Brahmins, Marars, Nambisans, Pushpakars, Variers, Nayars, Thiyyars, Malayars, Vedars, Kurichiyars, Pulayars, Parayars, or others. All these groups are preoccupied with ensuring that no community they consider beneath them dares to step out of line. If someone does, they will not find peace until they drag them down, trample them, and inflict harm.

It is unclear how much connection the Brahmins living in Malabar in the 1800s had with the Vedic culture that flourished in Central Asia some 6,000 years ago. However, it is understood that English East India Company officials made significant efforts to discover and preserve ancient Sanskrit texts. It is believed that they rescued many palm-leaf manuscripts, which were fading into obscurity, from remote households across the subcontinent. Even Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra (not a Vedic text) is recorded as having been preserved in this manner.

The communities immediately below Brahmins are the Ambalavasis. Their traditional occupation involves tasks within the temple. They are not discussed in detail here.

The community below them is the Nayars.

9. Smouldering Resentment and Verbal Codes That Diminish Skill

When speaking of Nayars, it may be necessary to mention one or more matters that some among them might find distasteful. However, the reality is that no one in this region can claim a superiority beyond the excellence that language codes impart to the software codes of life and mind.

This reality applies to everyone, from the Pulayans, Parayars, Cherumars, and others at the bottom, up to the elite Brahmins who held their chests high at the pinnacle of the verbal-code mountain, before the English Company and the English flag brought about a profound mental revolution in this land.

When discussing Nayars, the situation in Malabar differed slightly or significantly from that in Travancore. The issue may be that, in North Malabar, Nayars were just above the matrilineal Thiyyars, while in South Malabar, they were above the patrilineal Thiyyars. In Travancore, however, they were above the Ezhavas, Shanars, Chovvans, and others.

Who a person stands—above or below —profoundly influences his or her personality.

For instance, a Malayali working under English people in England will exhibit a markedly different personality compared to a Malayali working under another Malayali in a Malayali environment in the Gulf. This difference may be evident in their physical structure and mental disposition.

Similarly, the influence of those below also matters. For example, a Malayali conducting business in America with entirely English-speaking local employees may display a significantly different personality compared to one who employs only Malayalis and conducts business in Malayalam in the same country. I refrain from stating this with certainty because other factors influencing personality also exist, which cannot be addressed here.

I lived primarily in Travancore from around 1970 to 1983. The concept of a unified Kerala, as commonly imagined today, did not exist then. There is much to say about this later.

For now, let me state this much: in Travancore, Ezhavas harboured significant resentment towards Nayars, both overtly and covertly. In Malabar, both groups of Thiyyars and other lower castes were socially and linguistically under the Nayars by tradition. However, it seems that the matrilineal Thiyyars did not exhibit a similar resentment or hostility.

To illustrate this, I recall an incident. When my mother was a deputy department head and later department head in Thiruvananthapuram, and earlier, a district-level officer in Alappuzha, some Ezhavas would visit and express their deep-seated resentment.

A clear reason for this resentment might be that, until the Indian government subdued the Travancore kingdom, Ezhavas were restricted to menial government jobs. Changes were gradually occurring, but before that, the Indian administration forced the Travancore king to capitulate under military threat.

While such social issues existed across much of the subcontinent, nearly half of it was British India. In British India, any caste could access any government position, provided they had profound English language proficiency and the associated egalitarian mindset.

It is understood that, in the administrative system of Malabar District, many Thiyyars held high positions without caste-based job reservations. One Choorayi Kanaran is noted to have been a Deputy Collector in Malabar District.

Furthermore, it is known that some Thiyyars served in the highest ranks of the British-Indian Railway and as senior officers in the Imperial Civil Service (ICS).

Additionally, I have heard of a Thiyyar pilot officer in the British-Indian Airforce.

These historical factors may explain why the resentment seen among Ezhavas was absent among Thiyyars.

The Ezhava government employees who shared their grievances with my mother would also say, “We are all one group.” This was not acceptable to my mother, as it is a fact that matrilineal Thiyyars and Ezhavas have no traditional marital ties. Moreover, my mother’s stance was loftier than that of Brahmins. The declared stance was, “We are Thiyyas from Tellicherry,” and she would not entertain any discussion on caste matters.

However, one thing I learned from such people was their declaration that Nayars were mere Shudras, clearly intended to demean them.

In response, the Nayars’ declaration was that Ezhavas were mere “Kottis,” referring to the act of tapping coconut fronds with a small hammer to collect toddy.

Climbing a coconut tree is, in reality, an extraordinarily daring physical skill. However, when caught in the grip of feudal language, this is the outcome: a remarkable skill is reduced to a lowly occupation.

10. Imparting Divinity to the Software of Life

In several historical texts, Nayars are defined as Shudras. For instance, V. Nagam Aiya’s Travancore State Manual, Rev. Samuel Mateer’s Native Life in Travancore, Edgar Thurston’s works, and William Logan’s Malabar Manual all clearly state this. However, the Malabar Manual also provides a peculiar additional hint.

It notes that researchers like Mr. Fergusson and Dr. Buchanan Hamilton pointed out a remarkable similarity in tribal culture between the Newars of Nepal and the Nayar tribes of the Canara coast.

Two main aspects caught their attention. The first was the similarity in the architectural styles of these two groups. However, what drew even greater notice was the lifestyle of the women in these two tribal communities.

The case of the Newars cannot be discussed here. But for Nayar women, what particularly intrigued many foreigners at the time was the distinct difference in their marital life compared to other civilised communities of that era.

Among Brahmin Namboodiris, the eldest Namboodiri could marry within his own community. It is indicated that younger Namboodiris formed relationships with Nayar households. They could live with a woman from such a household through a formal ceremony called sambandham, though this bond had only limited social legitimacy and was often very short-lived.

Moreover, it is suggested that when Namboodiris visited Nayar households as guests, they had the right to form relationships with women they fancied. I recall someone mentioning that a hint of this practice appears in Chandu Menon’s Indulekha.

Children born from such relationships had no connection with their father or his family. Furthermore, Nayar women could have such relationships with different Namboodiris over their lifetime.

This was not considered repulsive, as it might be today. The reason is that the relationship was with a person socially recognised as divine. Understanding the mesmerising power of feudal language codes clarifies the rationale. When everyone stands in deference and displays subservience in a person’s presence, a relationship with that person unmistakably imparts divinity. Conversely, forming a bond with someone who receives no respect, is deemed lowly, or is a servile worker would, through language codes, reduce the person to something akin to a mere trifle.

English people have no understanding whatsoever of the divine rhythm hidden in feudal language words or the discordant rhythm that opposes it.

It is unclear how Nayars would receive the information mentioned above. However, the points highlighted here are as follows: below the Nayars were numerous communities. While Nayars served as overseers of Brahmin households, the communities beneath them were considered inferior castes of varying degrees. It is likely that the opinions of these lower castes were given no value by those above them. It must also be considered that the living standards of many of these lower castes were extremely poor.

This information should not be misunderstood to mean that the communities deemed inferior lived in grandeur while Nayars led a degenerate lifestyle.

Another point is that V. Nagam Aiya notes that the fraudulent historical text Keralolpatti suggests Nayars may have originated from the primitive Naga tribe. Nevertheless, it is also indicated that Nayars may have originated from Shudras.

A point to highlight here is that, over generations, Brahmin blood infiltrated the Shudras, so their bloodline and lineage would predominantly consist of Brahmin blood.

Another matter to note is that when a divine person’s offspring is conceived, the knowledge of that divine person influences the software codes of life. This knowledge facilitates positive designs in the offspring in the womb.

This operates in various ways. The social dissemination of this knowledge, the elevated verbal codes used in connection with it, and the heightened mental state it instils in the mind all exert influence.

Conversely, if the thought or social knowledge arises that the offspring in the womb is from a person of lower status, it triggers a negative code configuration. Such mesmerising codes do not exist in languages with flat codes, like English. More on this will be discussed later.

This subject is, in truth, an exceedingly complex matter. Delving into it now would make it uncertain when we might return to the main thread of the narrative. Therefore, I will not venture there.

11. Undermining the Social Movement That Upholds

When English rule gained strength in Malabar and government jobs, disregarding caste boundaries, became accessible to all based solely on English proficiency and related efficiency, Nayars in Malabar suddenly had to change their footing.

In Native Life in Travancore, Rev. Samuel Mateer writes:

QUOTE:

Sudras meeting Brahmans adore them, folding both hands together; the Brahman, in return, confers his blessing by holding the left hand to the chest and closing the fingers. END OF QUOTE.

Translation of Quote:

Shudras, encountering Brahmans, revere them with folded hands. The Brahman, in return, bestows his blessing by holding his left hand to his chest and curling his fingers. End of Quote.

Rev. Samuel Mateer portrays this scene as somewhat improper. However, the reality is that the respect and saluting shown by a police constable to an IPS officer, when mixed with feudal language, would seem even more bizarre to an English citizen.

Although Mateer’s depiction pertains to Travancore, such social scenes were likely common in most Hindu kingdoms across the subcontinent.

However, in areas under English rule, namely British India, things were completely upended. Among Nayars, the joint family system followed matrilineal inheritance. When English rule arrived in Madras and its ripples were felt in Travancore, concerns about the matrilineal system began to surface in various forms.

A father could not pass any property to his own children. The head of the family had to bear the financial responsibility for his sisters’ children. Moreover, many of the sister’s children lacked a father.

QUOTE from Native Life in Travancore:

Some of the more enlightened and educated Nayars are now beginning to realise their degradation, and to rebel against the Brahmanical tyranny, and absurd and demoralising laws under which they are placed. END of QUOTE.

Translation of Quote:

Educated Nayars (meaning those proficient in English) began to recognise their degradation and started speaking out against Brahmanical oppression and the absurd, demoralising, and morally degrading laws imposed on them. End of Quote.

This trend is akin to a constable raising a flag against an IPS officer. It is likely that Nayars in Travancore did not realise that this was an effort to undermine the social movement that elevated them above Ezhavas, Shanars, Chovvans, and numerous communities beneath them.

The reality is that toppling an IPS officer would also bring down the constable.

However, in Malabar, a remote district of the British Presidency of Madras, things were different. Toppling Brahmins would not significantly harm Nayars, as Brahmin dominance had lost its legal legitimacy.

QUOTE from Native Life in Travancore:

A society for the reform of the Malabar laws of marriage (and inheritance) has been formed at Calicut by the leaders of the Nayar community, especially those educated in English. END of QUOTE.

Translation of Quote:

Nayar social leaders, particularly those educated in English, formed a society in Calicut to reform Malabar’s marriage and inheritance laws. End of Quote.

The reason was that many English-educated Nayars began to resent the right of Namboodiris, who had lost their divine status, to interfere in their households. However, the matter does not end there.

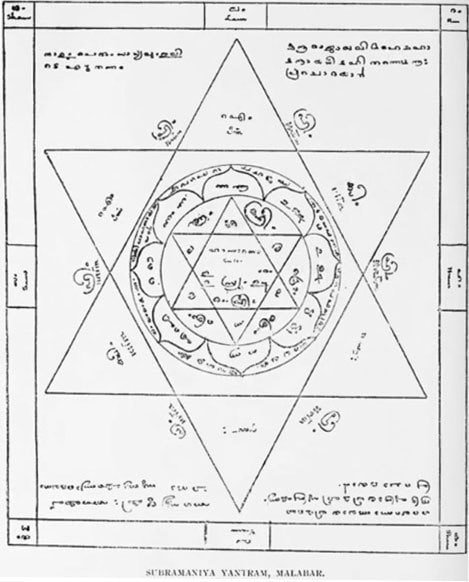

In feudal languages, the social power of individuals endowed with divinity over generations, their mantra-scented ancestral homes and temples, the various incantations associated with them, clan deity worship, spirit rituals, Vishnu festivals, fire ceremonies, sacrificial rituals, and more cannot be easily uprooted. This is because feudal languages, various occult practices, and conspiracies may indeed be intertwined.

12. The Underside of Feudal Linguistic Supremacy

Just as with the Thiyyars, it appears that among Nayars in Malabar, there was a dual disposition. It is said that Nayars in North Malabar generally held a sense of aloofness towards those in South Malabar. It is indicated that marriages between Nayar women from North Malabar and Nayars from South Malabar were prohibited in the north, with defiance leading to expulsion from the caste.

The events driving such peculiar forms of exclusion are unknown. However, it is recorded that people generally sought opportunities to climb into higher castes. Moreover, it is a fact that newcomers from foreign lands often devised plans to present themselves as belonging to a higher caste in their new region. In Travancore, Syrian Christians and Jews are noted to have displayed both cunning and shrewdness in this regard.

It is unclear how Nayars in South Malabar, North Malabar, and Travancore determined their relative status. However, when the English East India Company established its factory in Tellicherry, there is little indication of such distinctions. This was likely due to geographical reasons and the dangers associated with travel to distant places.

While the Nayars’ evident supremacy was driven by their Brahmin connections, its tangible outcome was their ability to suppress numerous castes through language codes. This suppression through language codes is akin to a wild animal’s bite. The bite of these wild beasts is like driving an iron nail into the body—once bitten, movement becomes impossible.

About 20 years ago, I visited the home of a revolutionary party leader in a rural area for some purpose. The leader was a Nayar and behaved with great courtesy. However, his wife was a woman of considerable haughtiness. It was clear she rarely ventured out or mingled with others. Despite having no prior acquaintance, she addressed me as “Inhi.”

The leader and his wife were surrounded by several young followers, all of whom they also addressed as “Inhi.”

The reality is that no communist movement can touch the grip, suppression, and biting control of such social codes.

Here, I must briefly digress from the main thread.

Consider a group of people who speak English fluently and pay little heed to others. This breeds significant resentment among others, who may view them as an insufferable lot. However, the reality is quite the opposite. Reflecting on one’s own language reveals that its words and sentences are biting and piercing. Those with discernment, moral judgment, and wisdom tend to steer clear as much as possible.

I won’t delve further into this tangent.

The incident at the communist leader’s house exemplifies the historical supremacy of Nayars. However, this trait is common across all communities.

Nayars in South Malabar, North Malabar, Travancore, and elsewhere may not necessarily belong to the same group. Yet, certain commonalities may be observed among them. Additionally, during the invasions of Malabar by Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, a significant number of Nayars are said to have migrated to Travancore for survival.

There are multiple tiers even among Nayars.

It was previously mentioned that Nayars are said to be linked to the ancient Nagas. Snake worship was a prominent practice in ancient Nayar households (tharavads). In many homes, cobras lived with their families and were treated as highly respected residents. Records of property sales, transfers, donations, or inheritance divisions from that era clearly and solemnly noted the presence of these snakes. Ensuring no harm came to them was a societal norm.

While lower castes like Pulayars and Parayars might kill snakes by hacking or shooting them, if Nayars learned of this, it could lead to trouble.

It is said that the sacred naga snake is not a cobra, but historical records clearly refer to cobra families.

Today, it can be said that such snake worship no longer exists among Nayars. It can also be added that Nayars no longer possess their former social grandeur.

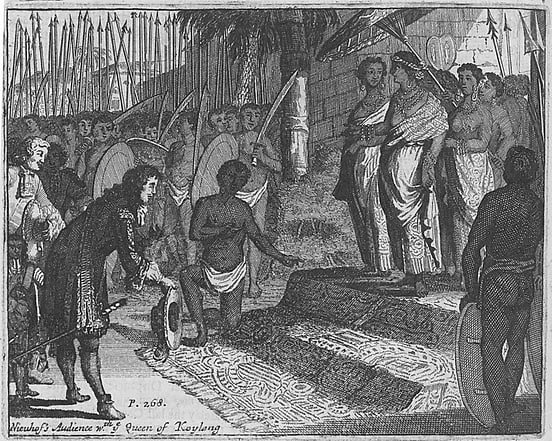

The image provided above, from Native Life in Travancore, depicts an aristocratic Nayar tharavad woman. To remain so elaborately adorned daily, one could hardly venture outside.

Last edited by VED on Fri May 02, 2025 4:30 pm, edited 1 time in total.

13. The Plight Within Aristocracy

Among Nayars, a joint family system prevailed. It is understood that grand tharavads with four-sided structures and central courtyards existed among the wealthier, higher-caste Nayars.

In some of these tharavads, there would be a sacred grove (sarppakavu) for snake worship and a bathing pond for women, located adjacent to the house.

From the outside, Nayar households exuded grandeur and female autonomy. This was because both women and men in these homes could address any lower-caste person approaching the house as “Inhi,” regardless of their age or professional skill. Lower castes could not avoid these households, as social authority resided within them. If lower castes quarrelled among themselves, the residents of these homes acted as the equivalent of the police constable or head constable of that era.

It is recalled from readings that different caste-based distances, tied to notions of ritual pollution, governed access to the sacred groves and how close one could stand.

Closely tied to this belief was the spiritual practice of tree worship. I observed, about 25 years ago in a northern part of Malabar, a daily ritual of lighting a lamp at the base of trees considered spiritually significant. This practice may still persist today. Such worship often protected these trees from timber merchants who roamed to fell them, as they were frequently revered by socially prominent locals.

However, it must be added that such beliefs offered no protection to the forest trees in Wayanad and similar areas. This is because, after 1947, when tribal forest dwellers were made Indian citizens without their knowledge or consent, most were relegated to the lowest verbal codes in Malayalam. Even the lowliest forest department peons defined tribal elders with terms like “Nee,” “Eda,” “Edi,” “Avan,” and “Aval” without hesitation. The dire consequences of this can be understood through language codes: the Indian bureaucratic class assigned negligible value to these communities’ property, bodies, minds, and trees. To enforce this degradation, tribals were forcibly taught Malayalam.

In the previous section, an image of a haughty Nayar woman was provided. Such a person was likely the matriarch (tharavattamma) of the tharavad. Beneath her would be numerous women and men. It is often written that Nayar women held significant social status and the personal authority to form relationships with any man of their choosing. However, these notions may be isolated assumptions, lacking any understanding of the social bonds and constraints shaped by language codes.

The reality is that, despite wielding considerable authority within the household, the matriarch likely had little opportunity to freely venture outside. Many women in these households would be confined, unable to step out, and relegated to repetitive, tedious household chores day after day.

The claim that Nayar women could freely form and shift relationships with any Namboodiri or Nayar man is likely untrue. Often, such decisions were made by their mother’s brothers or their own brothers.

Native Life in Travancore recounts an incident: A respectable Nayar youth, with a pleasing personality, once approached Rev. Samuel Mateer, weeping inconsolably. The reason was this: when he visited his wife’s home, her brothers barred him, saying, “We have chosen another man for our sister. Do not come here anymore.”

Not only was he separated from his wife, but he could no longer see his own children, a reality he found unbearable.

If a man displayed excessive personality or intellect, causing unease among his wife’s brothers or uncles, they might arrange for her to be given to another man. It was better to tread cautiously and deferentially.

Image: A photograph taken in the late 1800s, depicting a Nayar tharavad.

14. Falling into the Abyss of Language Codes

It seems that the general boastful tradition in South Asia can be likened to the character of Ettukali Mammuñju in Vaikom Muhammad Basheer’s story Ente Uppuppakku Oru Aanayundarnnu. The tendency is to claim that whatever good exists in the world was present here in its finest form.

Though there is little knowledge of what the true culture of this land was before the English East India Company raised its flag in Malabar, everyone with a modern education is well aware of the marvels that supposedly existed in ancient India thousands of years ago.

It has been written by some that the personal freedom enjoyed by Nayar women was unparalleled, even compared to modern America, where people from every fourth-rate nation flock and revel.

However, the reality is unlikely to align with such claims. The respect maintained within the household must be forcibly extracted outside, requiring restrained behaviour. Facial expressions, tone, and other aspects must be carefully curated. These are absent in English-speaking regions because the daunting concept of respect, as a rigid framework, does not exist in English language codes. Explaining this to English people is futile; some might naively argue that the word “respect” exists in English too.

Long ago, many Brahmin Namboodiri women remained unmarried. If some succumbed to temptations and transgressed sexual morality, they were often given to lower-caste slaves. In Travancore, when the London Missionary Society began converting lower castes to Christianity, many such women escaped this punishment by converting to Christianity, Islam, or Syrian Christianity.

The earlier-mentioned case of women from the Ettuveetil Pillamar’s households being sold to Mukkavars is related to this.

If Nayar women crossed caste boundaries and formed relationships with lower castes, their families would lock them up and later kill them with daggers or spears. However, if the king learned of this beforehand, he might save the woman’s life by selling her to Muslim traders or Christians.

There is a reference to a custom called Pula Pidi Kalam during the Karkidaka month (Native Life in Travancore). If a Pulayan saw a Nayar woman walking alone during this period, he could seize her. Moreover, if a lower-caste person threw a stone at a Shudra (Nayar) woman after dusk and hit her, she would lose her caste status.

In northern Travancore, Pariahs had a practice of abducting higher-caste women.

In February, after the harvest, Pariahs would gather in their temple courtyards, drink liquor, dance frenziedly in devotion to their deities, and, in an intoxicated state, invade the homes of Brahmins and Nayars (Hindus) under them, abducting women and children.

In 1516, Portuguese writer Duarte Barbosa documented such practices: during a specific month, Pulayans would strive to touch higher-caste women. At night, they would sneak into Nayar homes to attempt this. Nayar women took great precautions to avoid such incidents. If contact occurred, even if unseen, the woman would scream and flee her home, running to lower-caste households to save her life. If her family caught her, they would kill her for being “tainted” or sell her to passing trade caravans.

Thus, it is a fact that the bloodlines of lower castes in Travancore contain significant amounts of higher-caste blood. Yet, when crushed by the weight of language codes, one remains crushed.

The situation in Malabar was likely similar.

Does anything truly negative spread when a lower-caste person touches or verbally degrades a higher-caste woman? Consider this scenario:

A young female IPS officer is abducted by lower-ranking constables. They address her as “Nee” (Inhi), “Edi,” or refer to her as “Aval” (she). She performs their household chores and respectfully calls older constables “Chetta” (honoured elder brother) or “Chechi” (honoured elder sister).

Even if she escapes, resuming her role as an IPS officer would be fraught with issues. Moreover, an IPS officer addressed as “Edi” by constables and calling them “Chetta” or “Chechi” would become an intolerable entity to other IPS officers.

This harrowing depiction is meant to highlight the terrifying mental distortions caused by feudal language codes in this society long ago.

Ordinarily, such an incident is improbable today. However, just days ago, a commissioned officer in the Indian Army killed the wife of another commissioned officer and was apprehended by the Indian police. This must have been a festive occasion for police constables, akin to a Brahmin falling into the hands of lower castes. An individual accustomed to being addressed as “App,” “Saab,” or “Un” by thousands of ordinary soldiers in the army suddenly plummets, in a single day, to the level of “Thoo” (Nee), “Eda,” or “Avan” in the eyes of constables.

[Search YouTube for AEc7BkseB4A to view a related video.] (Note: The video has been removed from YouTube.)

The constables’ jubilant celebration might be visible in their eyes.

The profound provocative power of feudal language words and their ability to upend individuals and society are entirely unknown to English-speaking nations, making this a dangerously precarious condition for them.

Though there is little knowledge of what the true culture of this land was before the English East India Company raised its flag in Malabar, everyone with a modern education is well aware of the marvels that supposedly existed in ancient India thousands of years ago.

It has been written by some that the personal freedom enjoyed by Nayar women was unparalleled, even compared to modern America, where people from every fourth-rate nation flock and revel.

However, the reality is unlikely to align with such claims. The respect maintained within the household must be forcibly extracted outside, requiring restrained behaviour. Facial expressions, tone, and other aspects must be carefully curated. These are absent in English-speaking regions because the daunting concept of respect, as a rigid framework, does not exist in English language codes. Explaining this to English people is futile; some might naively argue that the word “respect” exists in English too.

Long ago, many Brahmin Namboodiri women remained unmarried. If some succumbed to temptations and transgressed sexual morality, they were often given to lower-caste slaves. In Travancore, when the London Missionary Society began converting lower castes to Christianity, many such women escaped this punishment by converting to Christianity, Islam, or Syrian Christianity.

The earlier-mentioned case of women from the Ettuveetil Pillamar’s households being sold to Mukkavars is related to this.

If Nayar women crossed caste boundaries and formed relationships with lower castes, their families would lock them up and later kill them with daggers or spears. However, if the king learned of this beforehand, he might save the woman’s life by selling her to Muslim traders or Christians.

There is a reference to a custom called Pula Pidi Kalam during the Karkidaka month (Native Life in Travancore). If a Pulayan saw a Nayar woman walking alone during this period, he could seize her. Moreover, if a lower-caste person threw a stone at a Shudra (Nayar) woman after dusk and hit her, she would lose her caste status.

In northern Travancore, Pariahs had a practice of abducting higher-caste women.

In February, after the harvest, Pariahs would gather in their temple courtyards, drink liquor, dance frenziedly in devotion to their deities, and, in an intoxicated state, invade the homes of Brahmins and Nayars (Hindus) under them, abducting women and children.

In 1516, Portuguese writer Duarte Barbosa documented such practices: during a specific month, Pulayans would strive to touch higher-caste women. At night, they would sneak into Nayar homes to attempt this. Nayar women took great precautions to avoid such incidents. If contact occurred, even if unseen, the woman would scream and flee her home, running to lower-caste households to save her life. If her family caught her, they would kill her for being “tainted” or sell her to passing trade caravans.

Thus, it is a fact that the bloodlines of lower castes in Travancore contain significant amounts of higher-caste blood. Yet, when crushed by the weight of language codes, one remains crushed.

The situation in Malabar was likely similar.

Does anything truly negative spread when a lower-caste person touches or verbally degrades a higher-caste woman? Consider this scenario:

A young female IPS officer is abducted by lower-ranking constables. They address her as “Nee” (Inhi), “Edi,” or refer to her as “Aval” (she). She performs their household chores and respectfully calls older constables “Chetta” (honoured elder brother) or “Chechi” (honoured elder sister).

Even if she escapes, resuming her role as an IPS officer would be fraught with issues. Moreover, an IPS officer addressed as “Edi” by constables and calling them “Chetta” or “Chechi” would become an intolerable entity to other IPS officers.

This harrowing depiction is meant to highlight the terrifying mental distortions caused by feudal language codes in this society long ago.

Ordinarily, such an incident is improbable today. However, just days ago, a commissioned officer in the Indian Army killed the wife of another commissioned officer and was apprehended by the Indian police. This must have been a festive occasion for police constables, akin to a Brahmin falling into the hands of lower castes. An individual accustomed to being addressed as “App,” “Saab,” or “Un” by thousands of ordinary soldiers in the army suddenly plummets, in a single day, to the level of “Thoo” (Nee), “Eda,” or “Avan” in the eyes of constables.

[Search YouTube for AEc7BkseB4A to view a related video.] (Note: The video has been removed from YouTube.)

The constables’ jubilant celebration might be visible in their eyes.

The profound provocative power of feudal language words and their ability to upend individuals and society are entirely unknown to English-speaking nations, making this a dangerously precarious condition for them.

15. Before the English Company Brought Social Light to This Region

It is recorded that Tipu Sultan made the following proclamation to the Nayars of Malabar:

QUOTE from MALABAR MANUAL:

And since it is a practice with you for one woman to associate with ten men, and you leave your mothers and sisters unconstrained in their obscene practices, and are thence all born in adultery, and are more shameless in your connexions than the beasts of the field: I hereby inquire you to forsake those sinful practices, and live like the rest of mankind. END OF QUOTE

Translation of Quote:

Since it is your custom for one woman to associate with ten men, and you allow your mothers and sisters to engage in unrestrained obscene practices, you are all born of adultery and are more shameless in your relationships than the beasts of the field. I hereby direct you to abandon these sinful practices and live like the rest of mankind. End of Quote

This quote appears to be related to Tipu Sultan’s military campaign through Malabar.

Reading this might give the impression that Tipu Sultan was a social reformer. However, his campaign was not a social reform initiative. Rather, it was an event that brought profound suffering to Hindus (Brahmins), Ambalavasis, their loyal Nayars, and the lower communities aligned with them. I won’t delve into that now.

The main focus of this narrative is how the light of English rule impacted the matrilineal Thiyyars of North Malabar. The discussion has shifted to the contexts of Namboodiris, Ambalavasis, and Nayars—those historically regarded as socially elevated—to highlight their grandeur and rituals, in order to explain what English rule brought to Malabar.

To understand the radiance of English rule, which rose like the sun in this region, one must first grasp the reality of the time. It seems there was no tradition of systematically documenting historical events in this land. For example, temples associated with Nayar tharavads can be found in many places, but there are no written records of their antiquity. Instead, only oral traditions passed down through generations exist. It is unclear to what extent such traditions can be considered history.

In Malabar, there were Brahmins, Ambalavasis, Nayars, matrilineal Thiyyars, patrilineal Thiyyars, Mappilas (Malabari Muslims), local Christians, Christians who converted from Travancore, and various communities labelled as lower castes.

Malabari Muslims are called Mappilas in Malabar, but in Travancore, the term Mappila refers to Syrian Christians. Historically, when Malabar and Travancore had little connection, this semantic difference was likely not widely recognised. Even today, this distinction persists, though rarely acknowledged.

It appears that many matrilineal Thiyyars, particularly those in the Tellicherry-Kannur region, benefited significantly from the light of English rule.

Before delving into that, I plan to briefly address the Odiyans—said to belong to the Pariyars of Malabar—before moving forward. This is just one of the hundreds of social issues English rule encountered in this region.

It was a form of grave sorcery. I will elaborate on this in the next section.

16. Sorcery, Black Magic, Massacres, and More

I don’t recall reading about Odiyans in Travancore. However, it is noted that certain groups, like the Kanikkars, were feared by higher castes, possibly due to the belief that they possessed tantric knowledge or performed occult rituals.

In Malabar, Odiyans were indeed a social reality. Similar diverse practices are said to have existed across various parts of the Madras Presidency.

It seems unlikely that young East India Company officers from England and other parts of Britain fully understood the realities they encountered in Malabar. In some northern regions governed by the same company, the practice of ritually burning women alive (sati) was prevalent, which struck them as utterly astonishing. Yet, locals appeared unfazed by it.

Since higher castes kept lower castes at a distance, the latter’s affairs were largely unknown to the former. However, English officers, unbound by the repulsive codes of local languages, could closely study the lives of even the most marginalised. A notable figure in this regard was Edgar Thurston, whose works, Castes and Tribes of Southern India and Omens and Superstitions of Southern India, stand as evidence.