Travancore State Manual by V Nagam Aiya

Travancore State Manual by V Nagam Aiya

c #

Commentary PART 1

Volume One Part 1

Commentary PART 2

Volume One Part 2

VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

Aaradhana, DEVERKOVIL 673508 India

www.victoria.org.in

admn@victoriainstitutions.com

Volume One Part 1

Commentary PART 2

Volume One Part 2

VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

Aaradhana, DEVERKOVIL 673508 India

www.victoria.org.in

admn@victoriainstitutions.com

Go back function

In a computer browser:

If you go to any other location or page by clicking on the links given here, you can come back to the previous location by keeping the Alt key on the keyboard pressed down and then pressing the Back arrow on the keyboard.

In a mobile browser:

If you go to any other location or page by clicking on the links given here, you can come back to the previous location by tapping on the Back arrow seen at the bottom of the mobile display screen.

Last edited by VED on Sat Feb 03, 2024 4:28 am, edited 11 times in total.

Commentary 1

1c #

A commentary to Travancore State Manual written by V. NAGAM AlYA, B. A., F. R. Hist. S., Dewan Peishcar, Travancore.

VED from VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

It is foretold! The torrential flow of inexorable destiny!

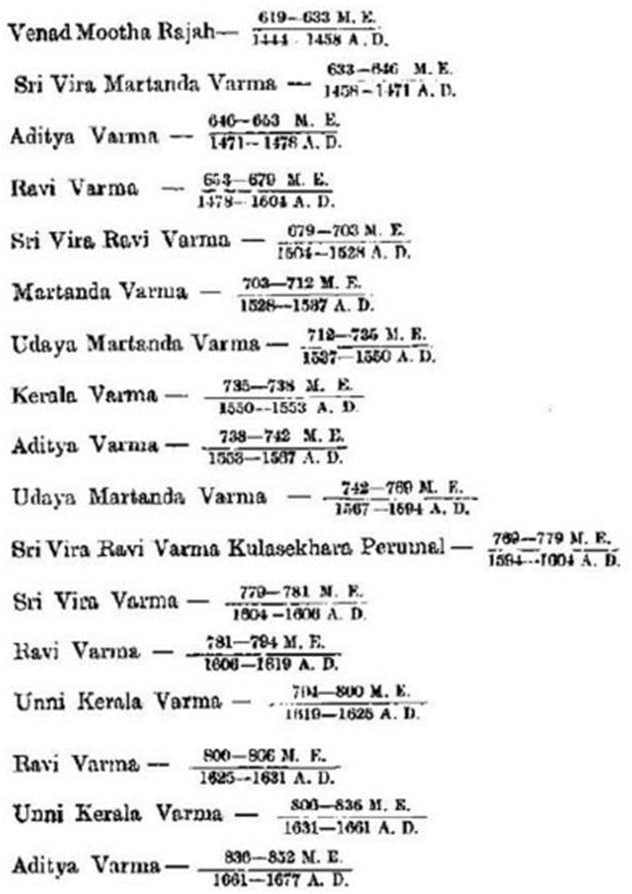

VOLUME ONE – PART 1

Commentary PART 1

1. Creation of a digital version

2. Cantankerous reasons

3. An unassuming talented historian

4. Observations

5. Slavery in the south-Asian peninsula

6. The peoples of Kerala

7. No mention of Mahabali

8. Classical case of cultural history manipulation23

9. How much trade contributes to cultural enhancement

10. Marthanda Varma; an anglophile

11. When slavery actually was liberation

12. Rama Varma

13. An antedating

14. Nayar pada [Nayar brigade]

15. Kesavadasapuram

16. A fake history not mentioned

17. Bala Rama Varma

18. Gouri Lakshmi Bayi

19. The tragic reign of Swati Tirunal

20. Trade and crude officials

21. The real reformers of India, Malabar & Travancore

22. The errors in social engineering

23. Repulsion for the word ‘Sudra’

24. What was happening in Malabar

25. Place names

26. A propitious relationship and a gullibility

27. Christian missionaries

28. What a fool did

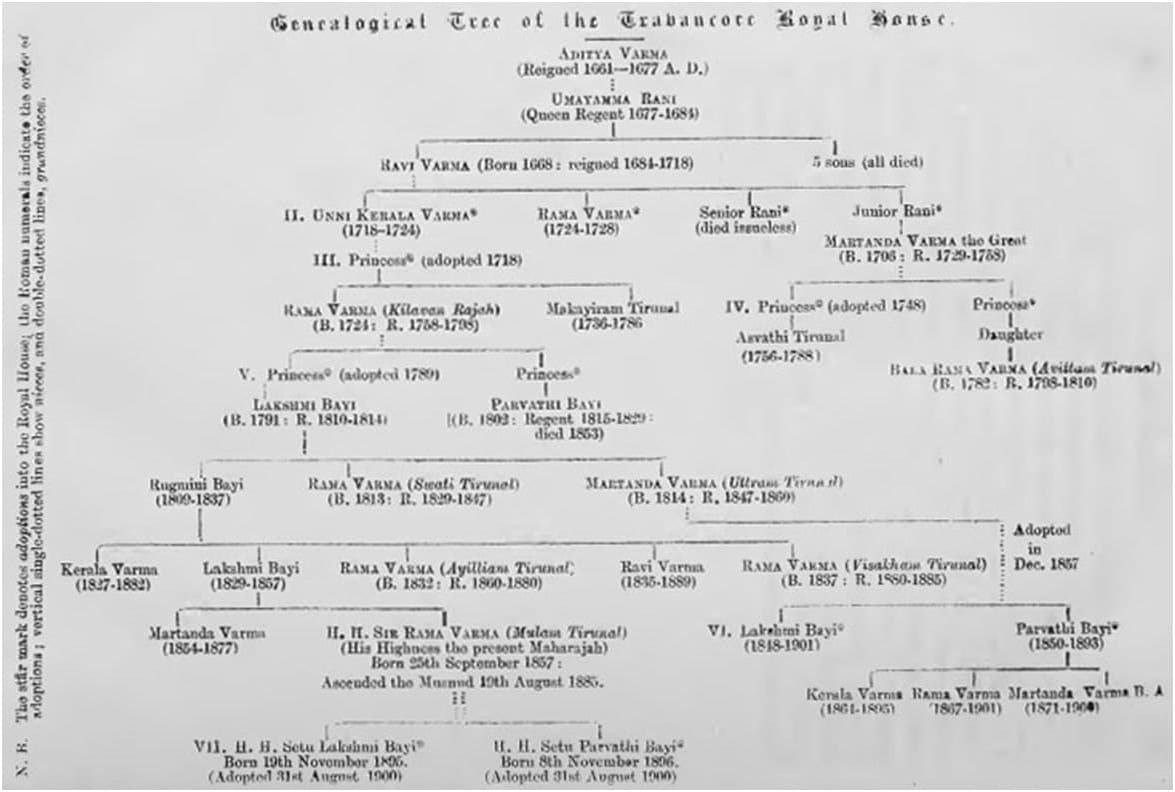

29. The Royal Family

30. General observations from this book

31. The current state of India

A commentary to Travancore State Manual written by V. NAGAM AlYA, B. A., F. R. Hist. S., Dewan Peishcar, Travancore.

VED from VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

It is foretold! The torrential flow of inexorable destiny!

VOLUME ONE – PART 1

Commentary PART 1

1. Creation of a digital version

2. Cantankerous reasons

3. An unassuming talented historian

4. Observations

5. Slavery in the south-Asian peninsula

6. The peoples of Kerala

7. No mention of Mahabali

8. Classical case of cultural history manipulation23

9. How much trade contributes to cultural enhancement

10. Marthanda Varma; an anglophile

11. When slavery actually was liberation

12. Rama Varma

13. An antedating

14. Nayar pada [Nayar brigade]

15. Kesavadasapuram

16. A fake history not mentioned

17. Bala Rama Varma

18. Gouri Lakshmi Bayi

19. The tragic reign of Swati Tirunal

20. Trade and crude officials

21. The real reformers of India, Malabar & Travancore

22. The errors in social engineering

23. Repulsion for the word ‘Sudra’

24. What was happening in Malabar

25. Place names

26. A propitious relationship and a gullibility

27. Christian missionaries

28. What a fool did

29. The Royal Family

30. General observations from this book

31. The current state of India

Last edited by VED on Tue Nov 21, 2023 9:21 pm, edited 13 times in total.

Commentary

1c #

1c1 #Creation of a digital version

There are a few reason why this book has been converted into a much easy to browse digital version. However, when this decision was taken, I had imagined that it would take only a few hours to do it. Or at the most three days. I had decided to depend on the digital version available online. However, it was only when I commenced the work that I found that there was a huge mountain of work to be done to design it into this digital book. The foremost problem being that the text on this online source was literally gibberish.

I decided to depend on a various other sources to get this book done. It was a wonderful experience in that this book gave me exact solid supportive evidence of the various contentions that I had made with regard to the working of feudal languages on social systems and their history [in my books].

I had to do a lot of typing to get the book into shape. Though a perfunctory proofreading was done, the book is not error free. It is a huge book of more than 300000 words.

I am surprised as to why books like these are not in the forefront on studies on ‘Kerala’ and ‘India’’ both, of the geographical areas that are identified with these names, and also of the modern state and nation that that bear these names. The answer to this query is not very hard to find. I have found that this book is a great evidence that British rule was not the evil experience that has been portrayed in writings of shallow Indian academic historians. Moreover, a lot of indoctrinations that are fed into the minds of the current day citizens of this nation shall stand questioned by this book, and similar books.

In fact, I have found that there are many other books also that are viewed with terror by a lot of people in various kinds of social leadership in Kerala and India. I know why such books as CASTES and TRIBES of SOUTHERN INDIA by EDGAR THURSTON, NATIVE LIFE IN TRAVANCORE by The Rev. SAMUEL MATEER, F.L.S. of the London Missionary Society, and many other books, including such books as THE STORY OF CAWNPORE by CAPT. MOWBRAY THOMSON are disliked. There are concerted efforts to see that these great books and real time researchers are pushed into the shadows. In fact, I have this very statement by some self-seeking person on Wikipedia India Pages that Thurston’s writings are not credible just because he is not an academician. See this Text in Wikipedia Talk Page by one person who has literally hijacked the Indian Pages:

QUOTE: The problem is not that Thurston was British, but that he was one of the British colonial administrators and not an academic.... END of QUOTE

I can only be amazed at the levels to which intellectual buffoonery has reached. I know of many persons, of fantastic intellectual levels, who have refused even to take an Indian MA, just because of the mediocrity it signifies. Yet, what they research is considered insignificant because they are not ‘academicians’!

1c2 #CANTANKEROUS REASONS

The major reason why these books are pushed away from limelight is that many of these books contain real insights on why the British rule was really the golden period in the history of the geographical area now containing Bangladesh, Pakistan and India.

The second point that arises is that the current day people of this area cannot bear the mention of any link to their ancestors. Instead of claiming any link to their very evident ancestors, whom they view with repulsion, they spin dubious stories and fables connecting them to populations with which their real link is extremely fragmentary.

Third is that many of the persons who are mentioned as great freedom fighters simply change into brutes when seen from a clearer perspective.

Fourth is the exact corollary of the last item. That is, persons mentioned as bad individuals are seen in a better light as being of benign disposition.

Fifth is the change in demeanour of certain historical persons from what they are generally supposed to be. For example, the Travancore Maharajah Marthanda Varma. If what is mentioned of him in this book has even a slight percentage of truth, then he is one of the great rulers that this peninsula has seen. In terms of clear understandings of what is what, he is seen as a great Anglophile.

Sixth is the negation of various claims of being the undisputed focus of social development by various caste organisations, when actually there is a wider context to all social development in Travancore, in the form of a supervising force at Madras Presidency. That is the English East India Company.

Seventh is a very funny claim by certain castes that certain other caste leaderships are their own sub-castes. That of Ezhava leadership claiming that Malabar Thiyyas are part of their own caste.

One sees a lot of mutual repulsions and claims among the various peoples who populated this geographical area. For instance there is this quote from Thurston’s book:

“The Tiyans are always styled Izhuvan in documents concerning land, in which the Zamorin, or some Brahman or Nayar grandee, appears as landlord. The Tiyans look down on the Izhuvans, and repudiate the relationship..................................An Izhuvan will eat rice cooked by a Tiyan, but a Tiyan will not eat rice cooked by an Izhuva”

However, it must be admitted that this superiority of Thiyyas could have been limited to the areas where the English education had been dissiminated by the English rulers. i.e. Tellichery and Cannanore. In the interiors of Malabar, the Thiyyas may have suffered from social suppression.

1c3 #AN UNASSUMING TALENTED HISTORIAN

There are many insights in this book. The writer of the main part of this book is V. NAGAM AIYA. I think that many Indian academic historians, who have endeavoured to write the history of ‘Modern’ India, should take lessons from this most unassuming writer, V. NAGAM AIYA. For, they have written the history of ‘Modern’ India in terms of and the perspective from, the Party congresses, meetings, terror activities, splits in political parties, and the doings, and ways and manners of various small-time political leaders who aspired to national leadership in the wake of the British Empire being dismantled all around the world by the foolish leadership of the British Labour Party. However, in this book, history is written from the perspective of creative activities, social improvements, educational developments, administrative reforms etc. done by the rulers.

In fact, there was always the possibility of writing it from various other perspectives in sync with the manner in which history of ‘Modern’ India has been written. For example, there was the continuous social rebellion by the Shanars in Travancore. If Shanars had taken over the rule, they would have written a history similar to that written by Indian academic historians. Containing the history of their various political meetings, memorandums, agitations, hartals, violent activities, shootings, bomb attacks and other political blackmails and intimidations. And about the various attainments of their various leaders.

Instead of that, this is a different kind of history writing in which the history of the nation is followed as it slowly moves from barbarian features to that of focused civilised achievements. The first thing that I noticed was the quality of the English. It is quite good, readable and yet perfectly scholarly. Not like the modern day academic pedants who pretend to more than they possess, and allude to more information than they can really assimilate.

One very striking point in the book is the usage of ‘honourable company’ with regard to the East India Company. This adjective of ‘honourable’ is a necessary item in the feudal vernaculars of the Indian peninsula. Without this adjective, (mentioned or unmentioned), words and attributes can go down. However, there is this issue. The same word can have severely differing meanings when seen from English and from Indian peninsular vernaculars perspectives. In English the sense of ‘an honourable man’ is that of a person who is honest, has rectitude, wouldn’t cheat, would keep his words, would be fair in dealings etc. However, the vernacular sense is none of these. Here it is a forcible imposition meaning that the entity has to be ‘respected’.

1c4 #OBSERVATIONS

Since I had the opportunity to go through the text when I was typing the text, I did notice certain things which I would like to bring a focus to.

One is the use of the word ‘European’. It has been variously used to mean the White people from Europe. And also the word ‘Western’. Both these words do need some inspection. Many times, it is used in the sense of the British. However, there is powerful information that needs to be inserted here. One is that Britain itself has four native languages. Of these, the Welsh, Gaelic and Irish might be Celtic languages and might have some feudal (hierarchical codes) elements in them. Then there is English, which is the language with which Britain is generally identified with. However English is basically the language of England and is a ‘planar’ language.

Beyond that there is this thing also to be noted. That England was the small island which the other nations of Continental Europe tried many times over the centuries to subdue, but almost always failed. So the use of the words ‘European’ and ‘Western’ to mean both the England or Britain along with that of Continent Europe might have an error in it. For, Continental Europe is not the same as England. In fact, in many ways it is the exact antonym of England and everything English. Many Continental European nations are different from England and English systems. This might be clearly discerned through their language codes.

See this quote:

If educated young men can show that they can equal Europeans not only in the capacity to do good service, but in the strictest integrity in every sense of the word, it will be a great thing accomplished for our community

Here the word ‘European’ is actually used in the sens of ‘Englishmen’

It must be emphasised here that the word ‘Europeans’ is used here as a synonym for the English national. For, in no way could one identify such nations as Portugal, Spain, France, Germany etc. as been equal to England. For instance, it was the Portuguese and Spanish Conquistadors who ravaged the South and North American continents for around 300 years, enslaving the native Red Indians there. The natives ultimately received a respite only in the areas which were later taken over by the English pioneers. This place is currently occupied by the USA. Which separated from England and went bonkers.

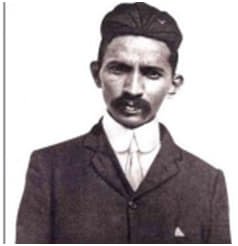

‘Ben Gandhi’

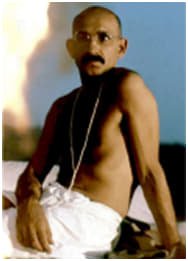

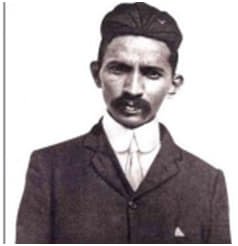

The second item that must be laid down here is about the peoples of Travancore. Just by reading about a people, one wouldn’t exactly know what it is one is reading about. There is always a need to have a picture of the person/s in mind. Otherwise one can make the same mistake that Attenborough created in the movie Gandhi. His Gandhi looks like an English man with English body language. See this (above) picture of the film-Gandhi.

Now see the real looks of Gandhi.

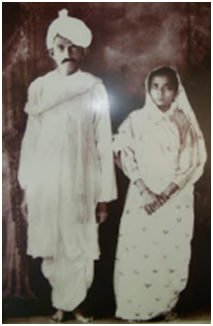

It is like another fake story film made about a north Malabar ‘King’. He and his tribal supporters are seen fighting against the British in this fake story film. See the depiction of the tribal folks in the film.

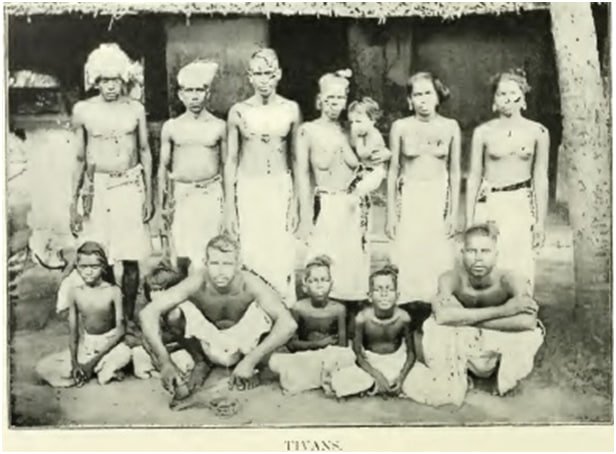

Look at the real looks of tribal folks then, in nearby areas.

Picture from CASTES and TRIBES of SOUTHERN INDIA by EDGAR THURSTON

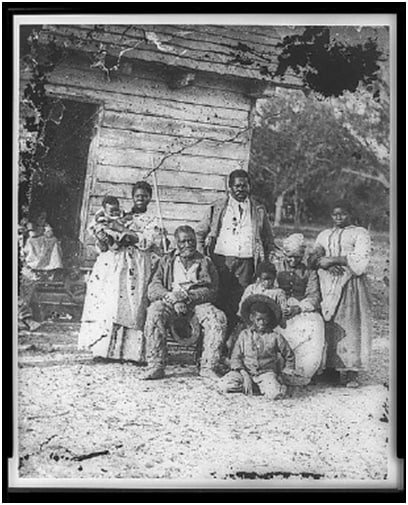

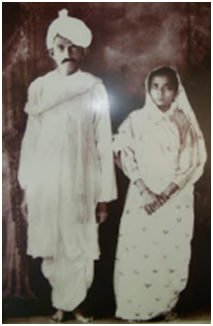

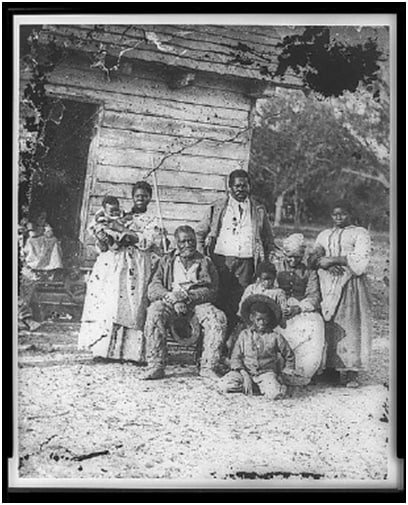

I am inserting here the following pictures to do a comparative study about the peoples of Travancore and Malabar and also two pictures of the so-called black slaves of USA in the beginning years of that nation’s creation:

First is a picture of the black ‘slaves’ of the USA of around 1860s. They are seen wearing modern clothing, sitting on a chair. And the females decently dressed. Circa 1862

Second two pictures👇 of labourer class folks of Ezhava/Chovvan/Nadar/Shanar (Travancore people) of similar times.

Third is a picture of Nair (supervisor-caste) females of similar times.

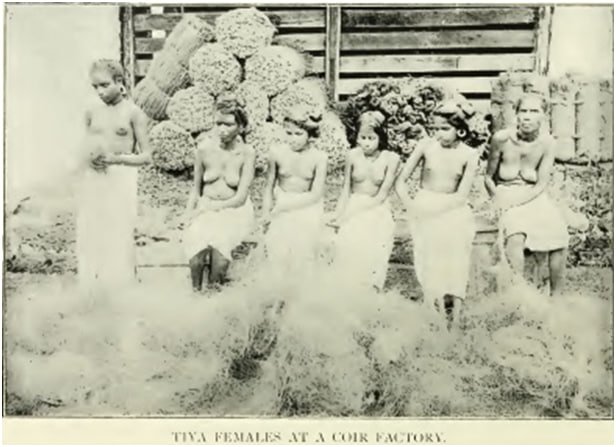

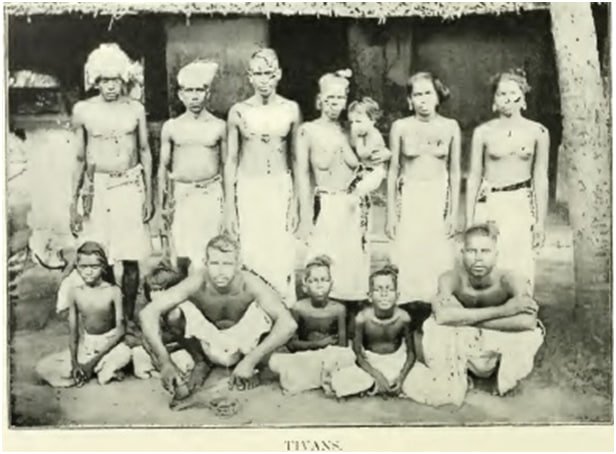

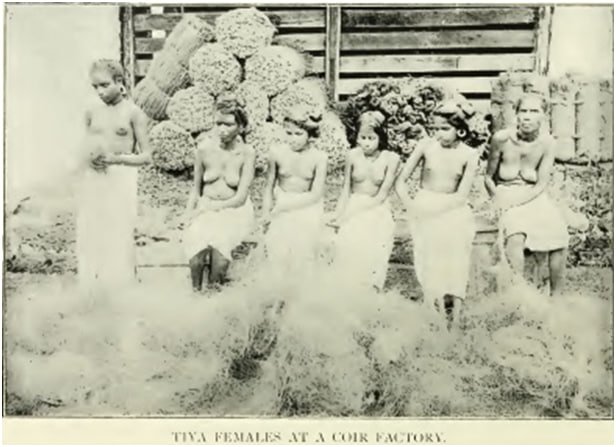

Fourth are pictures of Thiyya working class (Malabar people) of similar times.

Pictures from CASTES and TRIBES of SOUTHERN INDIA by EDGAR THURSTON

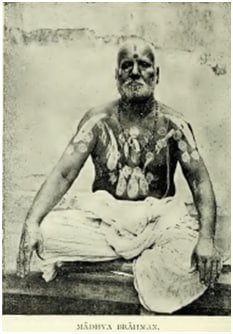

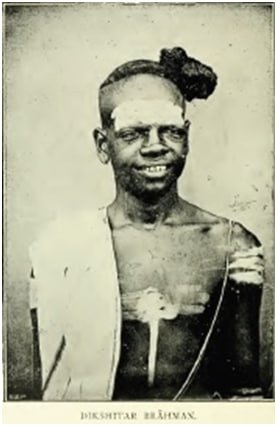

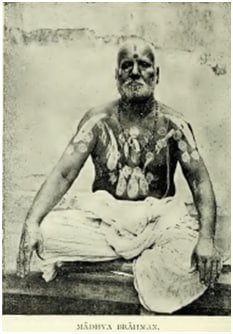

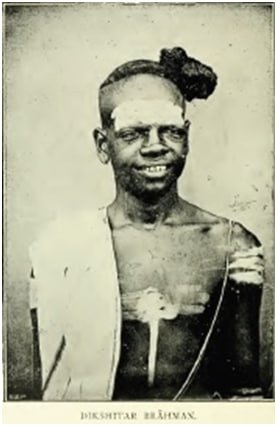

Fifth is a picture of Brahmins of the same time and area.

Picture from CASTES and TRIBES of SOUTHERN INDIA by EDGAR THURSTON

Sixth is a picture of the slave classes of the South Asian (Indian) peninsula

Picture from NATIVE LIFE in TRAVANCORE by REV. SAMUEL MATEER

Seventh is a picture of the blacks who were saved by the British West African Squadron from Arab Slave traders in the same period in history. They bear their real native looks, as apart from the black slaves of USA.

Pictures 2, 3, 4 and 5 are of free people. 1 and 6 are slaves. The first being slaves in an English society and the sixth slaves in Indian peninsula. The seventh is the real looks of free blacks before they received access to English social systems.

These pictures are placed here to give the exact context to the subject matter. Otherwise, the reader may move to erroneous understandings of the people/s about whom this book is about.

1c5 #SLAVERY in the South-Asian PENINSULA

Now this brings us to the topic of slaves. The general feeling is that slaves were only in the US and other similar nations. And that too the blacks. It is not true. Slaves were in the Indian peninsula, and most other nations, including Africa.

See these quotes from this book:

1. The Perumals. ...................... They also established Adima (bondage) and Kudima (husbandry), protected Adiyar (slaves) and Kudiyar (husbandmen) and appointed Tara and Taravattukar.

2. a piece of land near the city with the hereditament usual at the time of several families of low caste slaves attached to the soil.

3. There were also slaves attached to the land and there were two important kinds of land tenure, Ural or Uramnai subject to the control of the village associations, and Karanmai or freeholds, directly under the control of the state.

4. But when the nobles pass from place to place, they ride in a dula made of wood, something like a box, an which is carried upon the shoulders of slaves and hirelings.

5. our Paraya slaves taken away by the Sirkar and made to work for them as they pleased

6. The four Pottis among the conspirators were to be banished the land, the other rebels were to suffer immediate deaths and their properties were to be confiscated to the State. Their women and children were to be sold to the fishermen of the coast as slaves.

7. By a Royal Proclamation of 1812 A.D. (21st Vrischigam 987 M.E) , the purchase and sale of all slaves other than those attached to the soil for purposes of agriculture e. g,, the Koravars, Pulayas, Pallas, Malayars and Vedars, were strictly prohibited, and all transgressors were declared liable to confiscation of their property and banishment from the country. The Sirkar also relinquished the tax on slaves. But the total abolition of slavery and the enfranchisement of slaves took place only in 1855, as will be seen later on.

8. Amelioration of slaves. In 1843 the Government of India passed an Act declaring that no public officer should enforce any decree or demand of rent or revenue by the sale of slaves, that slaves could acquire and possess property and were not to be dispossessed of such on the plea that they were slaves, and that acts considered penal offences to a free man should be applicable in the case of slaves also.

9. the Resident in his memorandum, dated 12th March 1849, urged on the Dewan the improvement of the condition of the slaves as far as it could be done without affecting the interests of private proprietors of slaves.

10. This beneficent policy was soon followed by the total abolition of slavery in Travancore by the Royal Proclamation of 24th June 1855.

11. The Act above referred to for the abolition of Slavery, the encouragement given to Education, many liberal acts for the benefit of his people....

12. That prosperity extended to Travancore also, especially since the abolition of predial slavery in 1855

1c6 #THE PEOPLES OF KERALA

Even though I started converting this book into a digital book due to my interest in the historical and sociological aspects of the time and area, there are other chapters connected to other things like Geology, Flora, Fauna etc. I have tried to type the contents with as much accuracy that my general interest in the book would permit.

Now looking at the History part, it seems to depend on the book Keralolpathi for the ancient history. Even though I am not an expert in these things, I feel that overemphasis is given to this book which is mentioned as being in written in 1600s. So there is not much historical accuracy to be expected from this part. Moreover, the people mentioned in this book do not have much connection to the present populations Kerala. The present day populations would include

1. the Marumakkathaya antiquity Thiyyas of North Malabar (who are mentioned to have reached the Malabar shores from somewhere in the Kazakhstan region in the beginning years of the Christian era),

2. the Makkathaya Thiyyas of South Malabar (many of whom converted into Islam to form the Valluvannaad Mappillas),

3. the Shanavars of Travancore area, who are associated with such similar castes like Nadaars, Ezhavas, Chovvans etc. Ezhavas are mentioned as coming from Ezham or Ceylon,

4. the Syrian Christians who claim to be higher caste Hindu converts or may be even offspring of outside Christian missionaries members of days of yore, [This mention is not fully correct. They were actually the descendents of a foreign Christian group, which by certain treaties with the reigning king of Travancore, got higher caste status. See my Commentary on Malabar Manual by William Logan]

5. Christians who were converted from Shanvar, Ezhava, Paraya, Pulala etc. (and who populate the majority Christians of Malabar settler communities),

6. the lower castes who were more or less enslaved and attached to soils such as the Pulayas, Malayans etc.,

7. the Mappillas of North Malabar who were the offspring of Arab traders in native women,

8. the Mappillas of South Malabar who were converts from Makkathayam Thiyyas,

9. the Methan Muslims of Travancore who could be converts from Hindu lower castes.

10. Fishermen folks who come under various names such as Mukkuvar, Marakkan etc. There are Christian, Muslim as well as Hindus among the fishermen folks.

11. Apart from all this, there are the so-called superior groups of individuals in the Muslims like the Thangals, Sheiks, Rawuthars c&. Some of them claim direct blood line to Prophet Muhammed.

12. Then there are the so-called Anglo-Indians, who in North Malabar were connected mainly to British blood. In Mahe, it was French rule. So there must be French blood also to a limited extent. One should not forget that Portuguese as well as Dutch blood could also have entered here.

12. Apart from all of them, there are the off spring of various conquering groups including those who came from the East Tamil nadu areas as well as the infrequent raids by the Mysore Sultans, such as Sultan Tippu, and even the short duration rule of ‘Mogul pada’ in Travancore area. These raids naturally did aim at forced fornication of the women in the attacked areas.

So to connect the incidence mentioned in Keralolpathi to the present day populations of Kerala may not be correct. Apart from that Thurston does mention that people did have the habit of changing their castes to higher castes when they relocated to distant areas. In those days, a distant area would be just some fifty kilometres, for the majority people. Tied as they are to their soil by various social forces, including the terrible feudal content in the local vernaculars.

1c7 #NO MENTION of MAHABALI

Apart from all this, there is this that I noticed. That no mention of Mahabali is there in this antiquity which has been connected to fable and myth. In fact, there can be no connection of modern day Kerala populations to Mahabali. For one thing, this Mahabali’s land is mentioned as populated by a people who were very trustworthy, honest, non-treacherous, non-betraying, non-cheating, dependable and such. Moreover, the current populations of Kerala speak the official version of Malayalam (a language that was developed quite artificially in South Central Travancore). Malayalam itself is having no more antiquity than some 400 years (the father of this language is mentioned as having lived in some 400 years back). Culture-wise and by social dispositions, Mahabali’s people are quite different from the current day people of Kerala. Another point is the issue of how come a population is celebrating the words, that ‘we are not honest or anything good, but then such good people did live in this land thousands of years ago. Their language was not Malayalam’.

1c8 #CLASSICAL CASE of CULTURAL HISTORY MANIPULATION

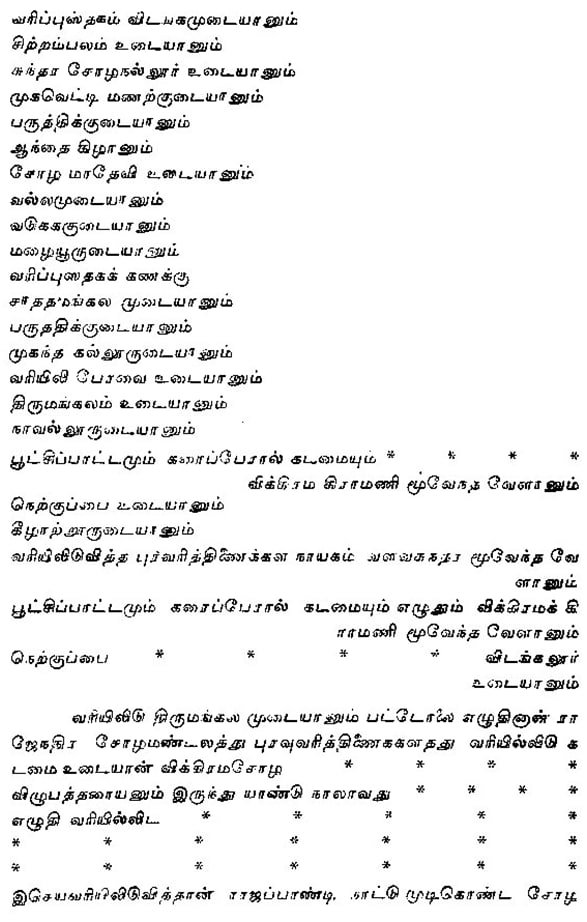

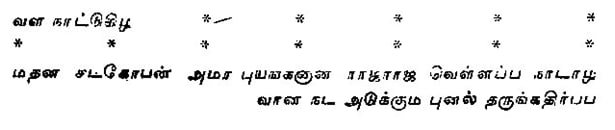

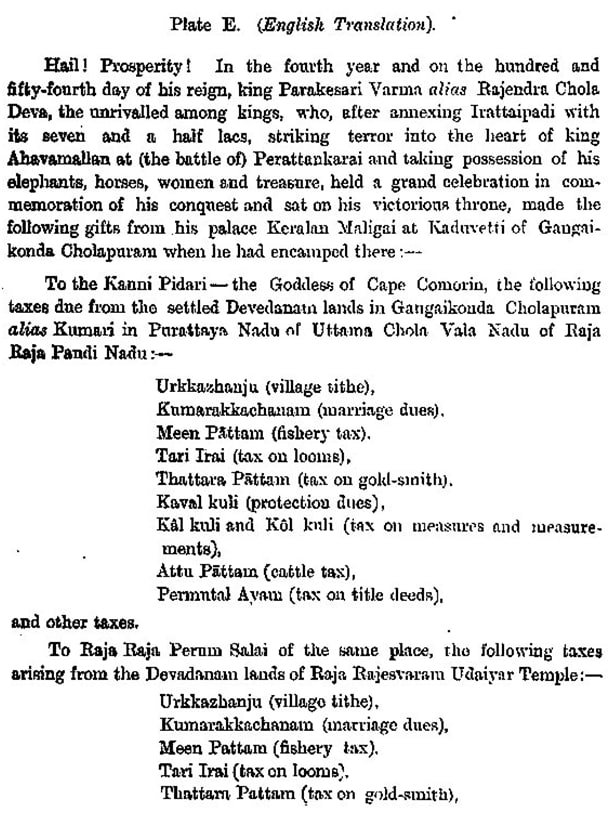

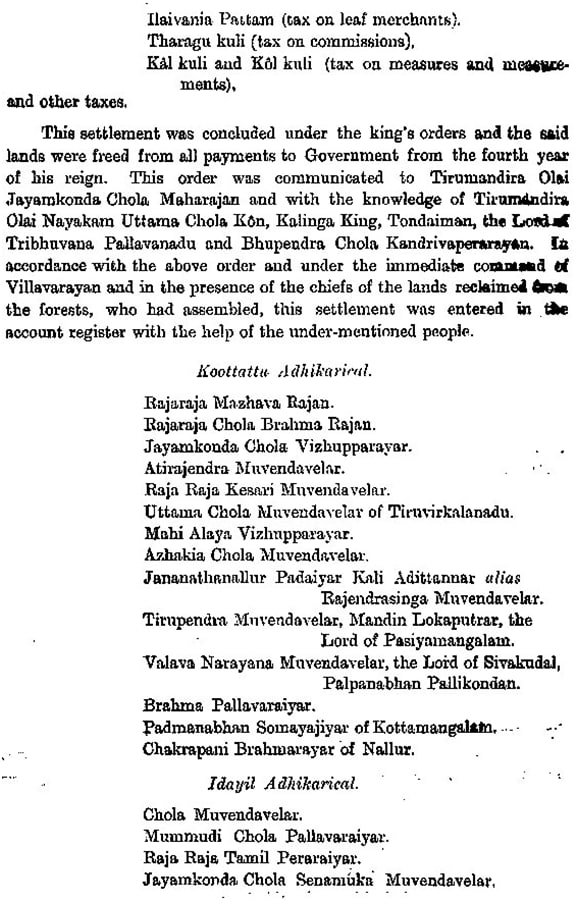

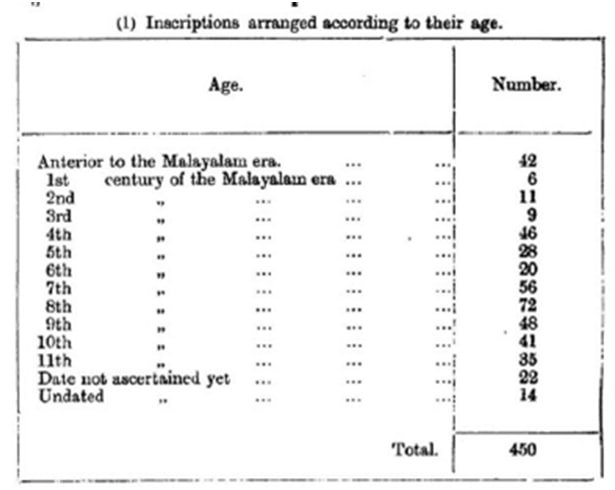

This discussion reaches us to the theme of Malayalam language. See this QUOTE from this book:

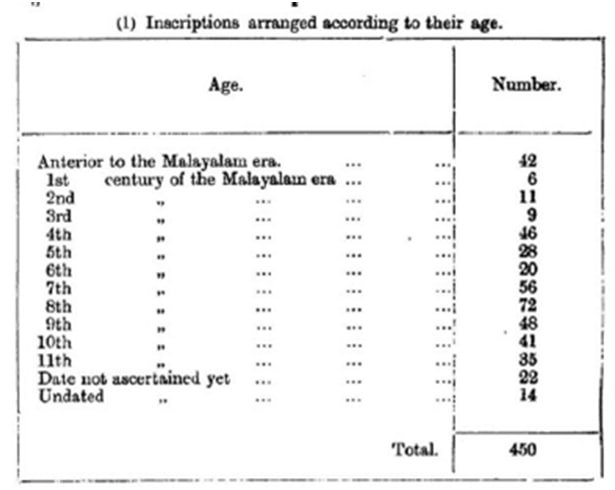

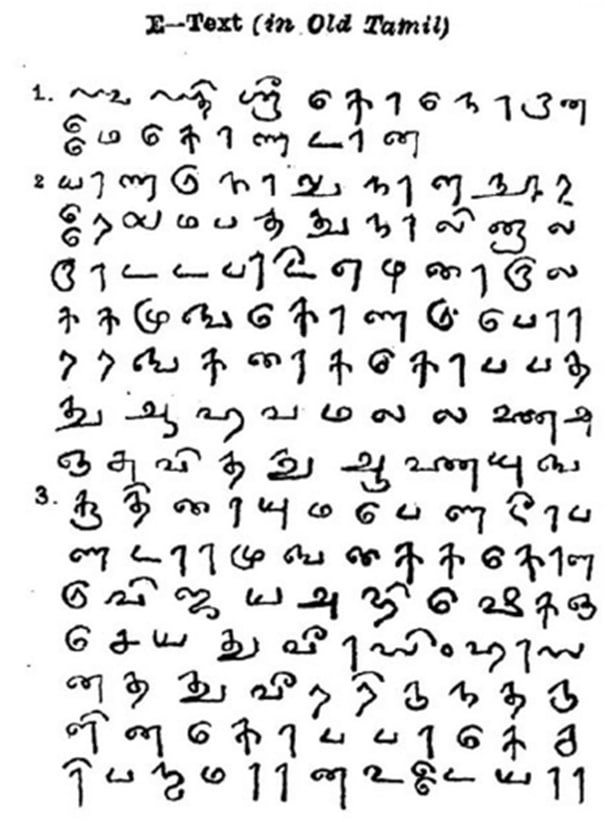

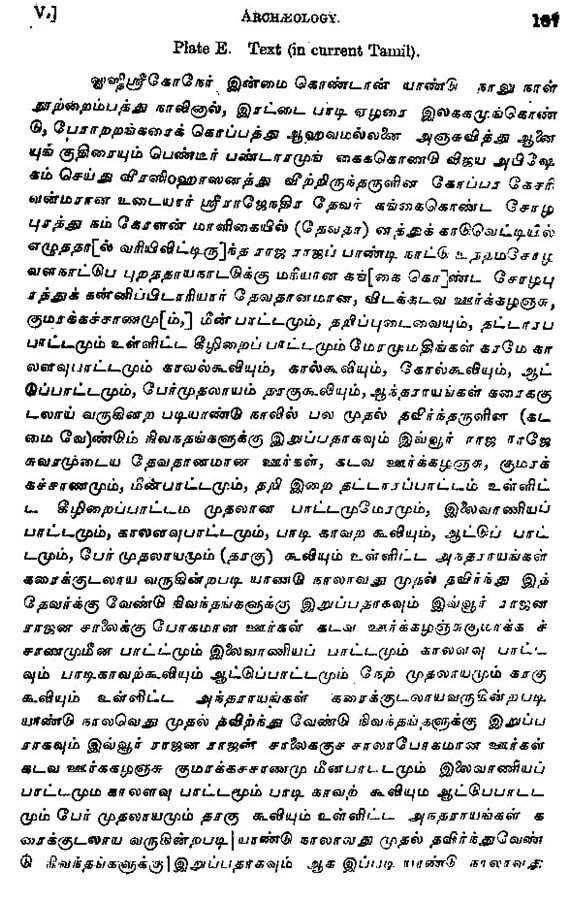

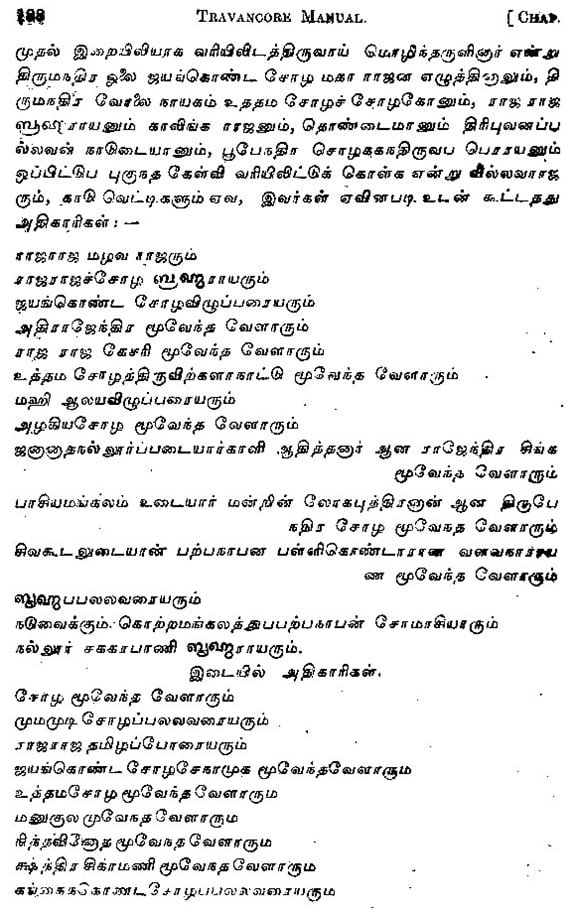

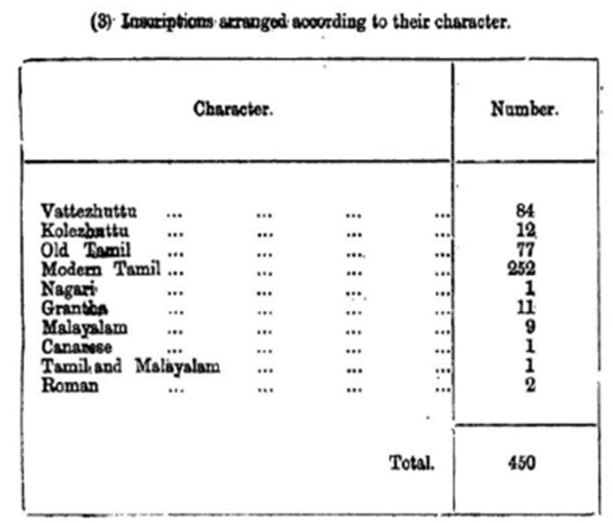

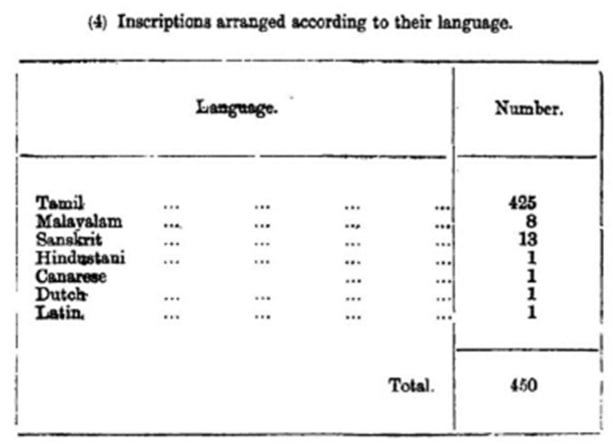

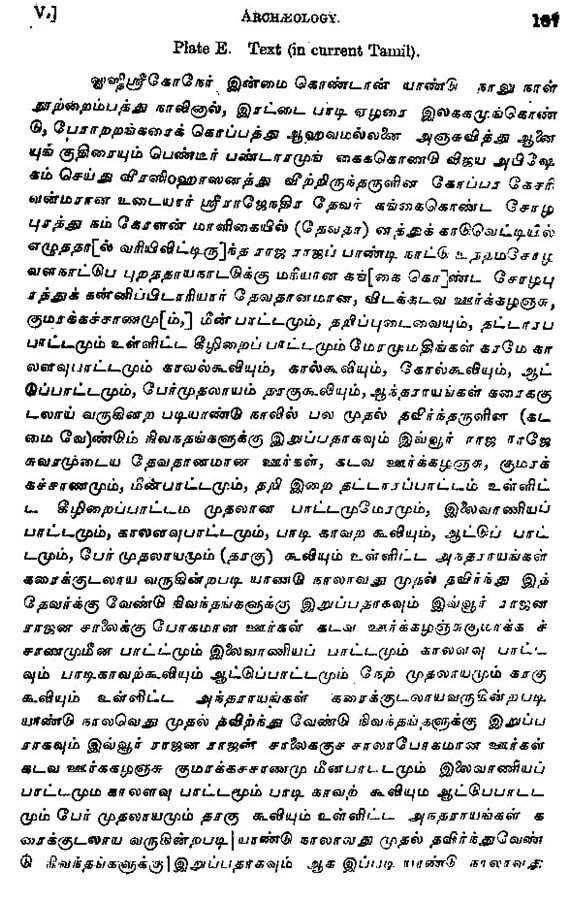

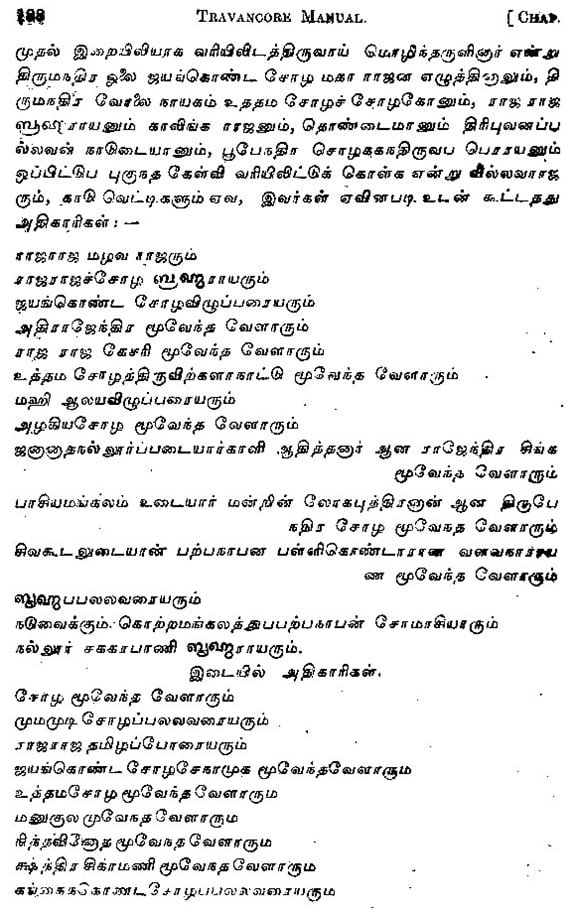

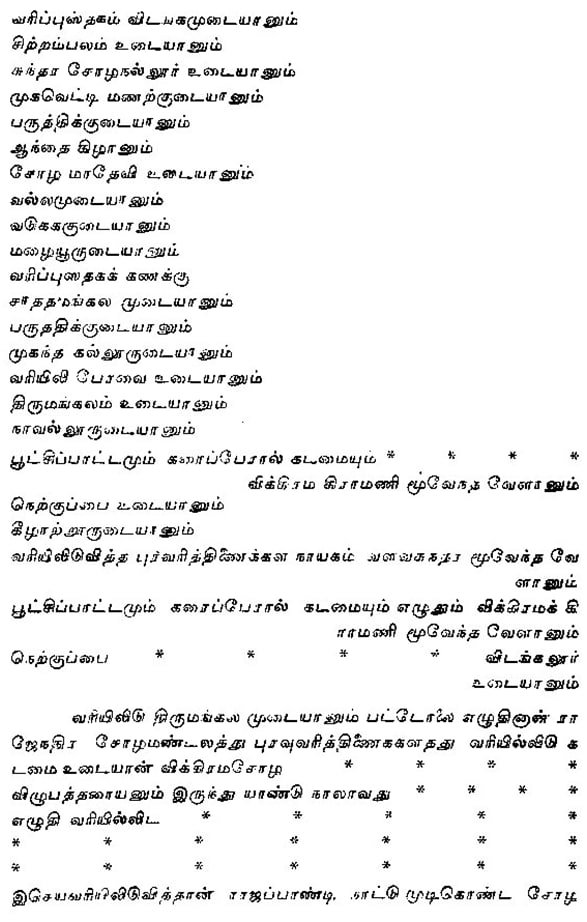

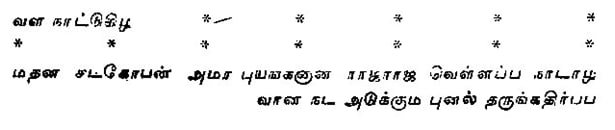

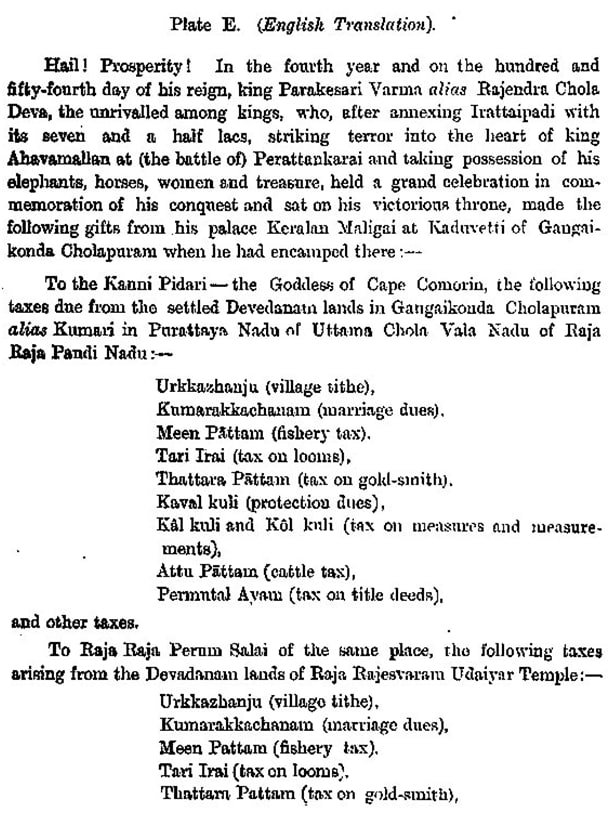

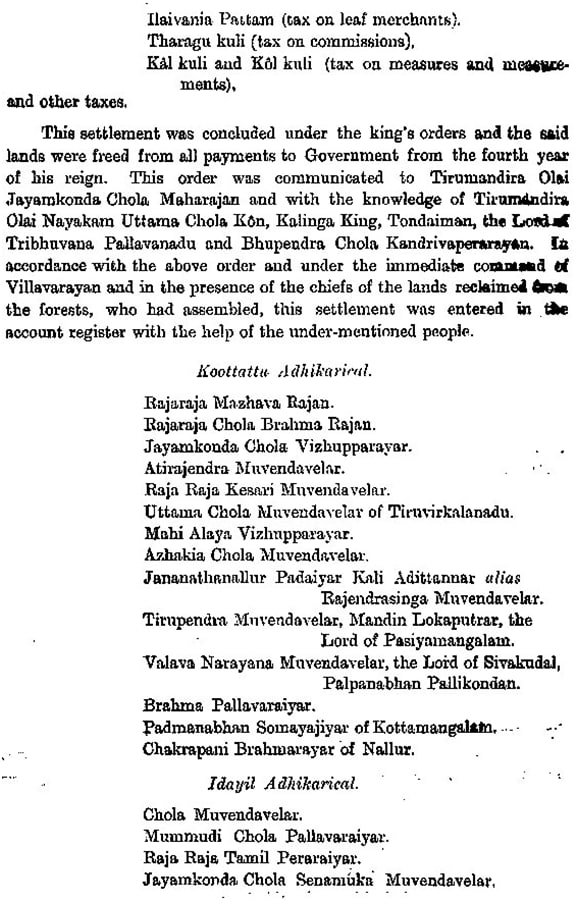

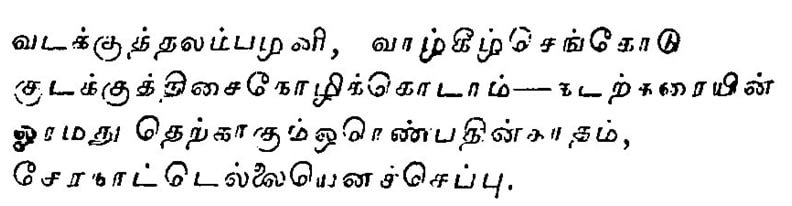

Another fact disclosed by the statements already given is that the language of most of the inscriptions is Tamil. The reason here is equally simple. Malayalam as a national language is not very old. Its resemblance to old Tamil is so patent that one could hardly help concluding that Malayalam is nothing more than old Tamil with a good admixture of Sanskrit words. There are some very old works in Tamil composed in Travancore and by Travancore kings. Besides, the invading Pandyas and Cholas were themselves Tamilians and their inscriptions form more than 70 per cent of the total in South Travancore. The Sanskrit inscriptions are very few and record ‘Dwaja Pratishtas’ and other ceremonies specially connected with Brahminical worship.

This discussion should include the fact that the language of Malabar was entirely different from that of the current day Malayalam. Words such as were the common words of Malabar. However, such words, ഊയ്യാരം, ഒതിയാര്ക്കംo, ചൊത്ത, ബരത്തം, പാഞ്ഞ്, ചാടുക, പെരിയ, മോന്തി, മൊത്തി, മയിമ്പ്, ചരയിക്കണം and even this entire language, have vanished from the knowledge of the younger generation in the last 20 to 30 years. Due to a very fanatical aim to impose a language from South Kerala. The funny thing is that these persons have been able to gather a Classical Language Status to this minor dialect of South Central Travancore, by the using routes of activity which in Mahabali’s period would have seemed quite shocking and absolutely unacceptable.

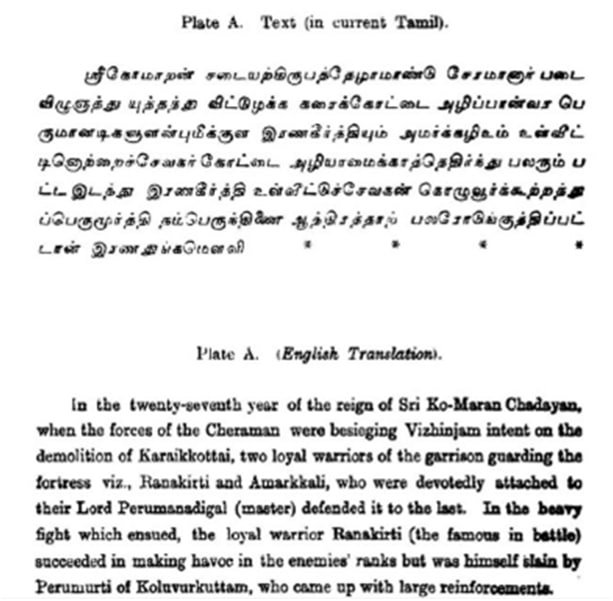

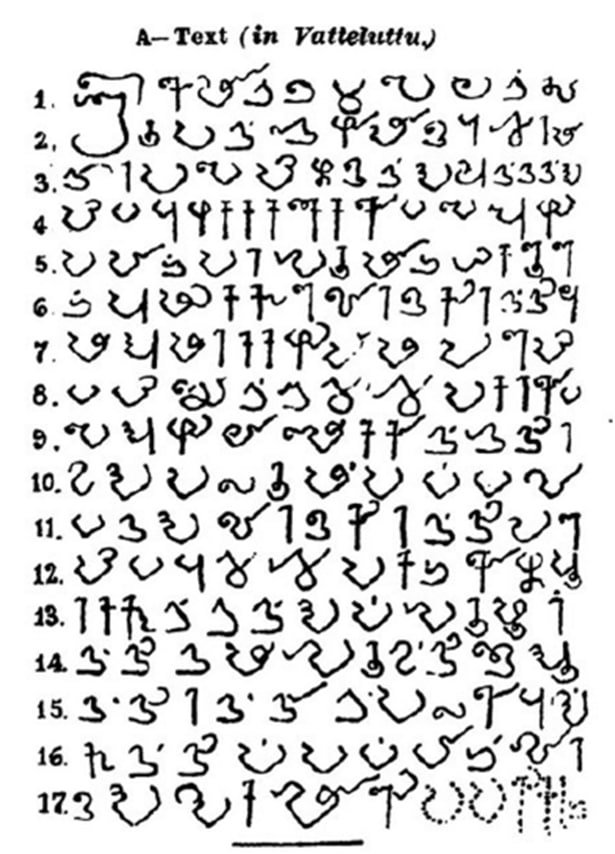

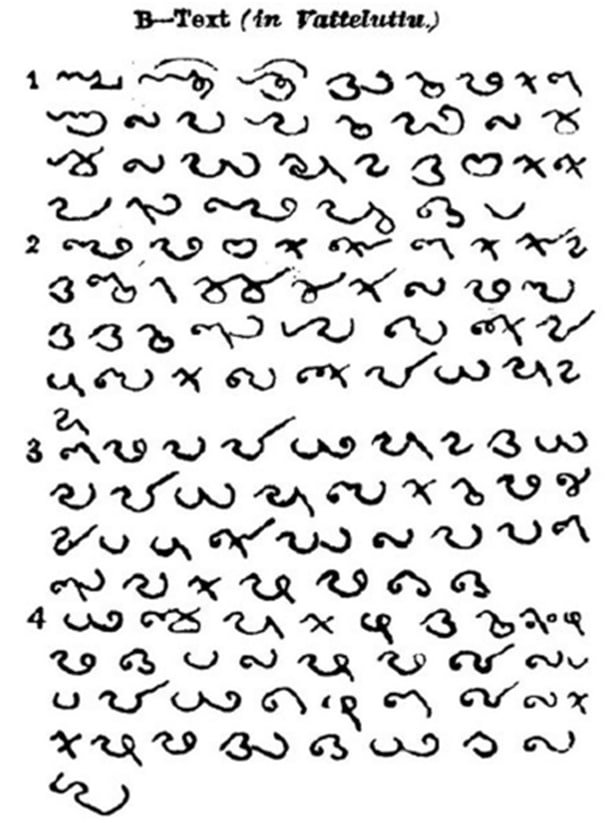

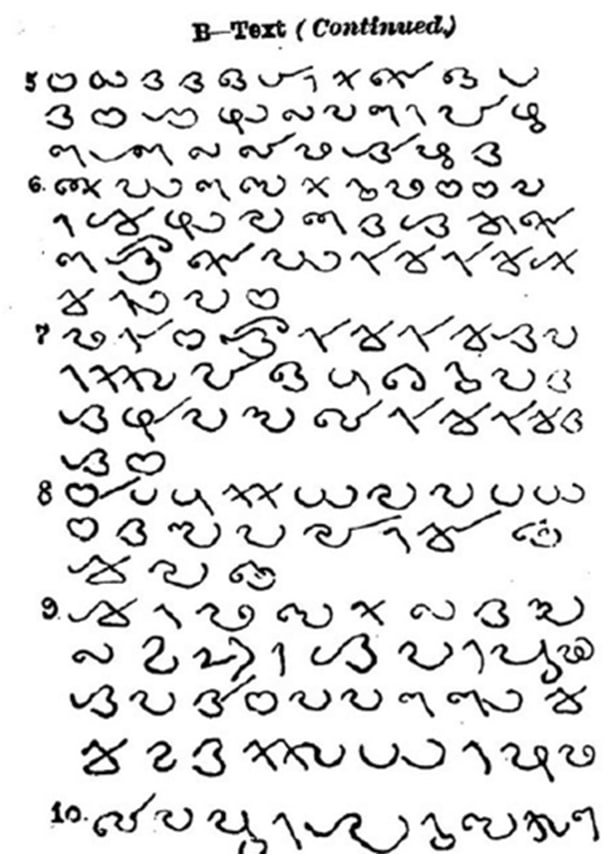

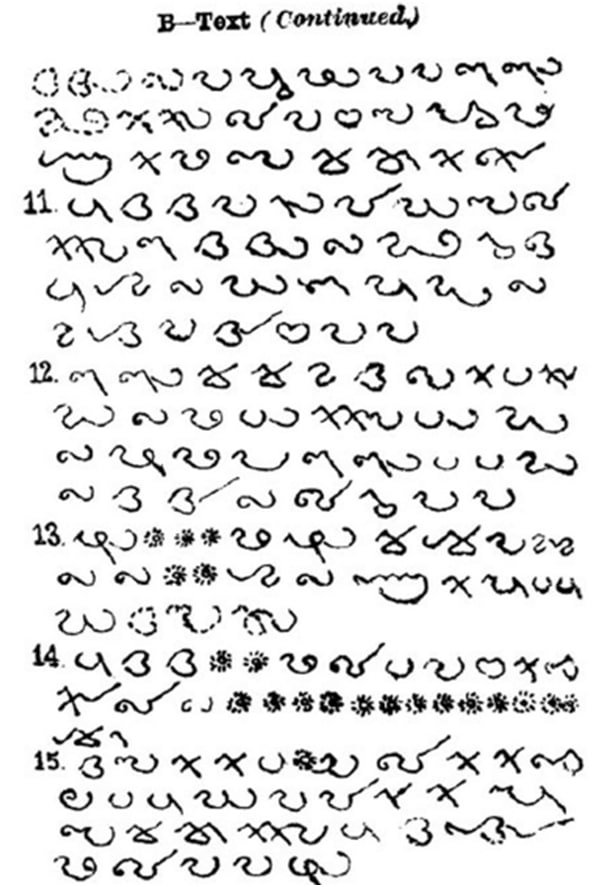

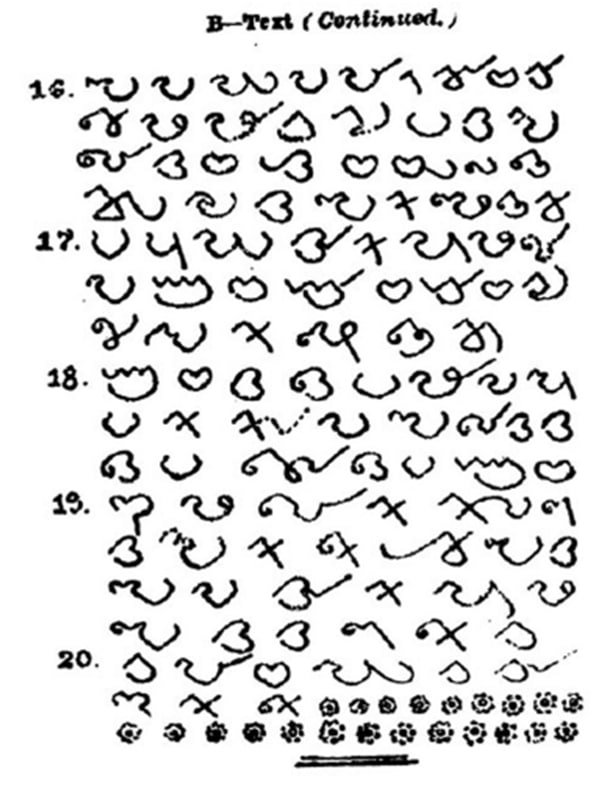

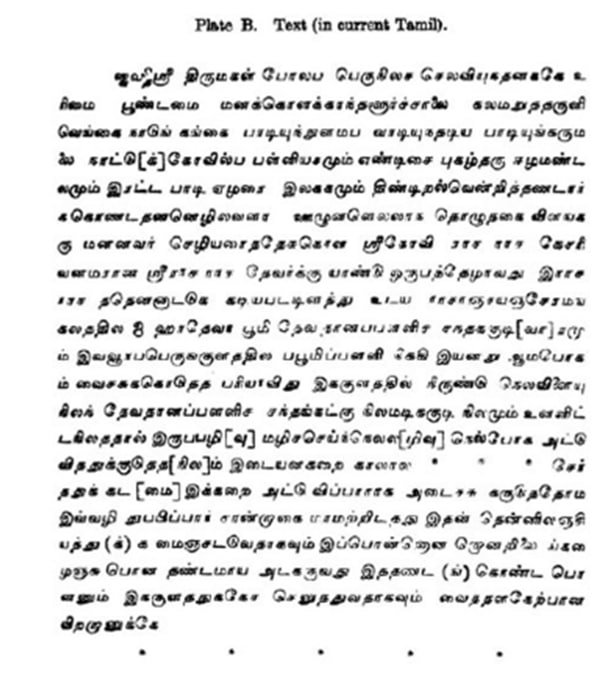

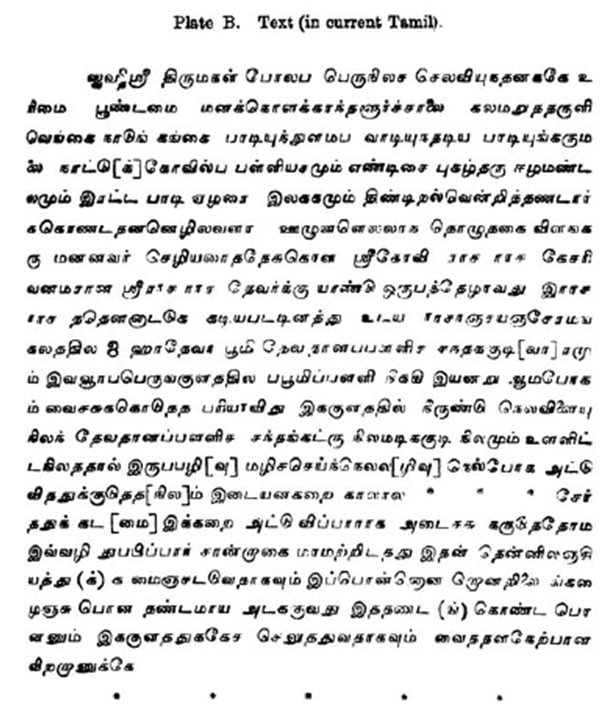

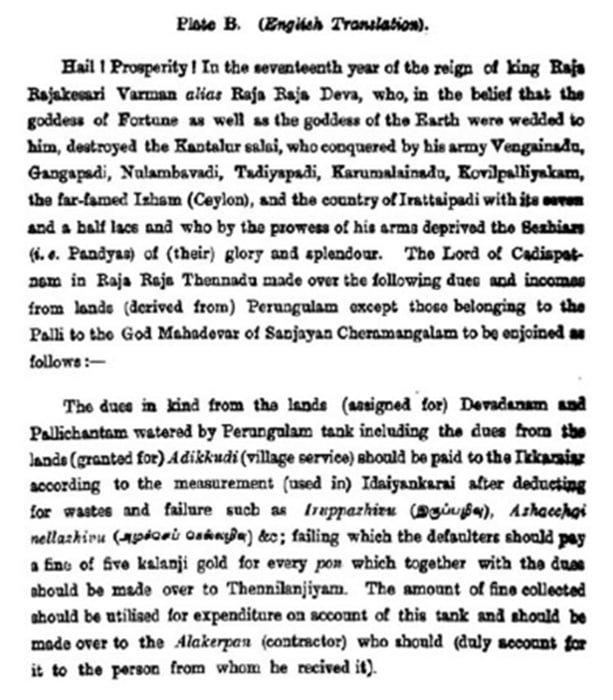

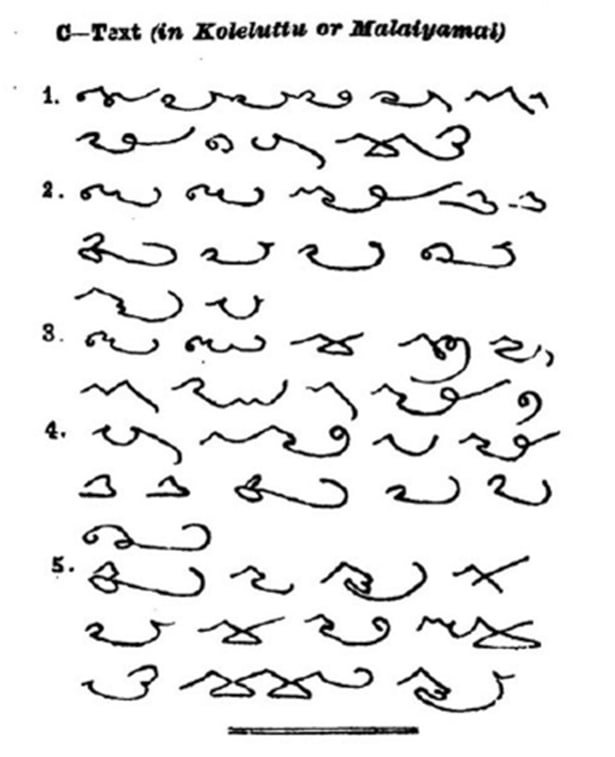

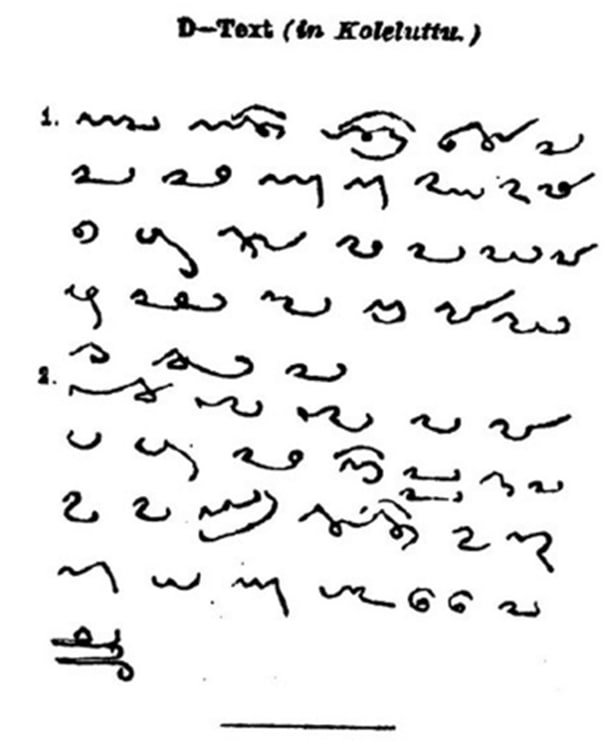

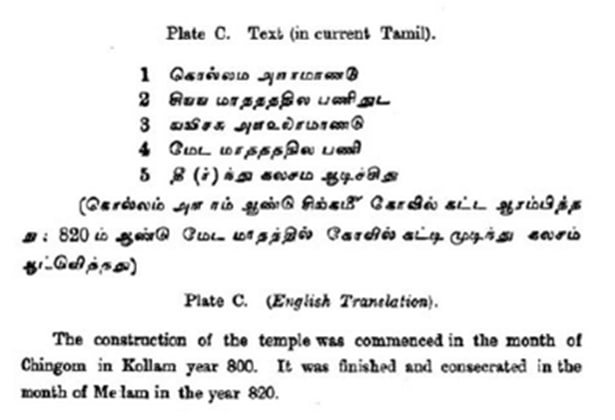

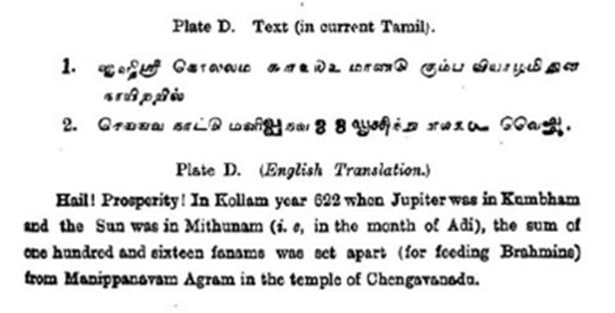

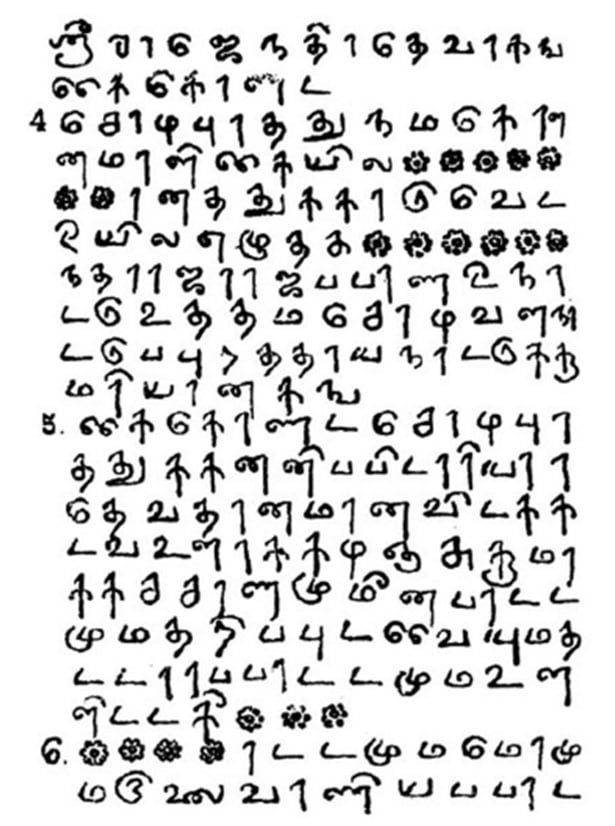

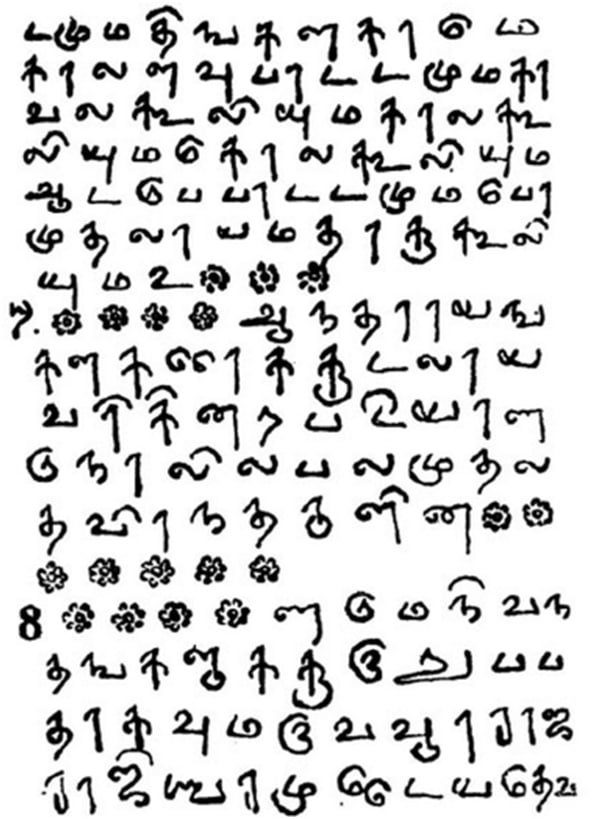

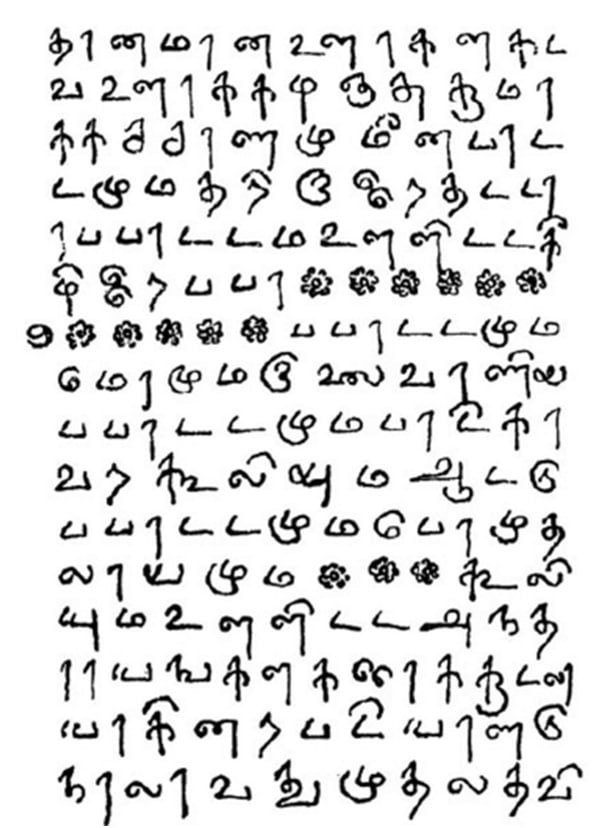

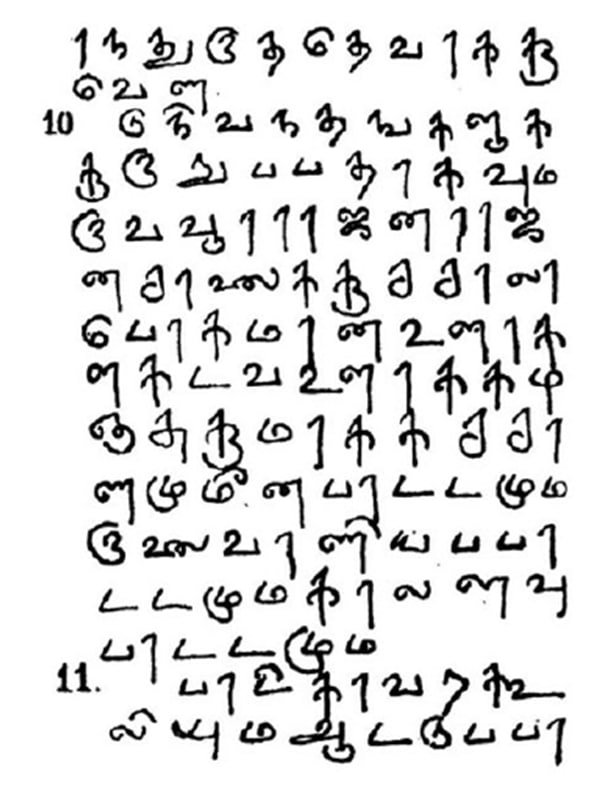

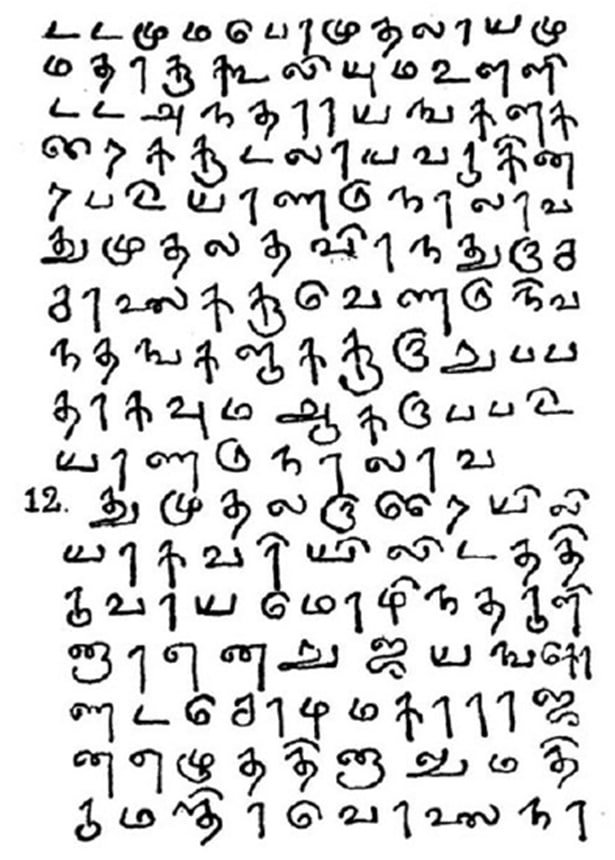

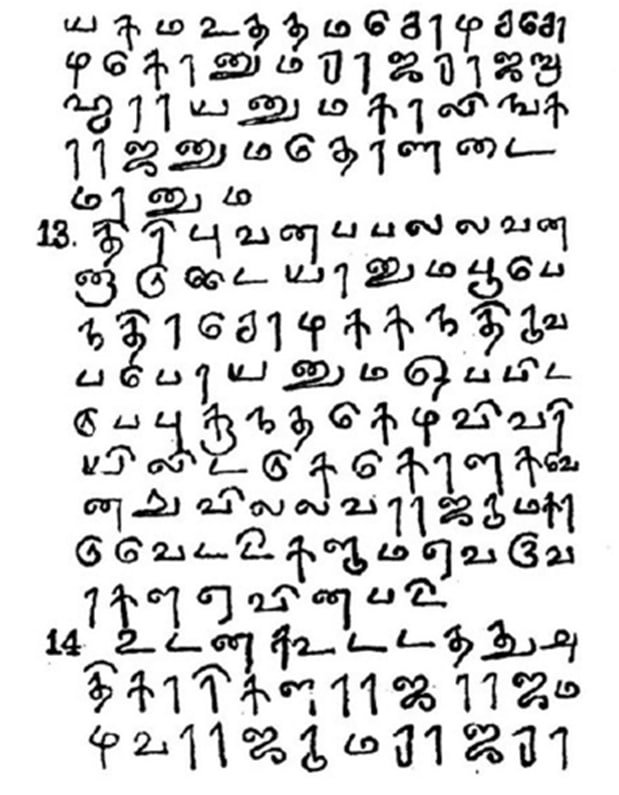

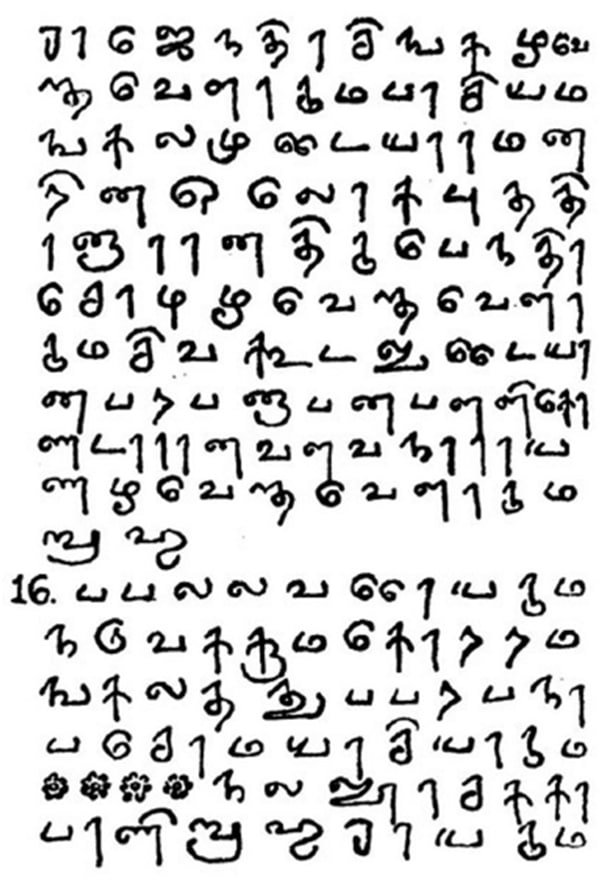

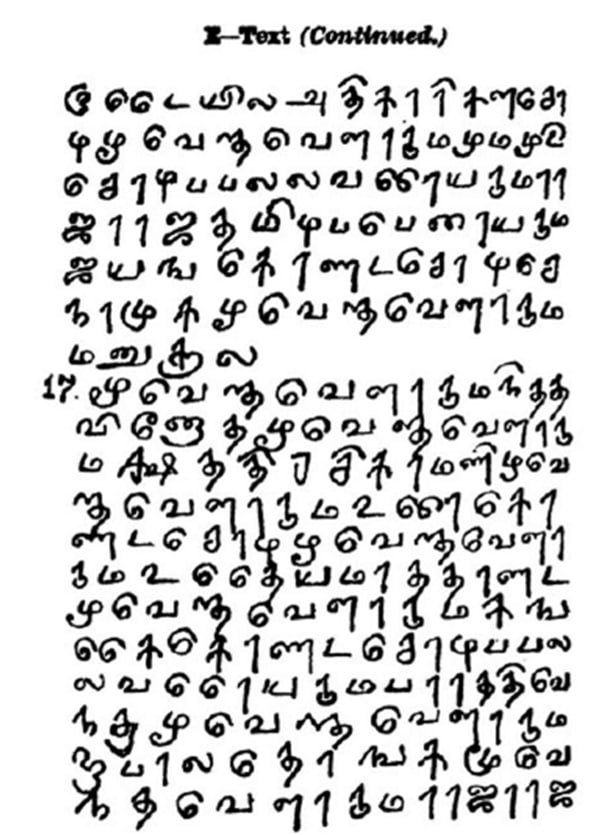

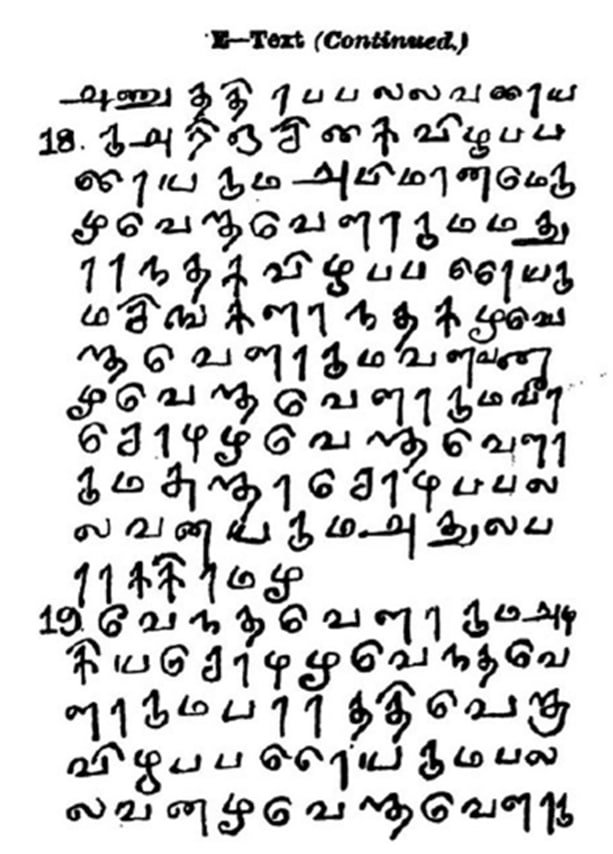

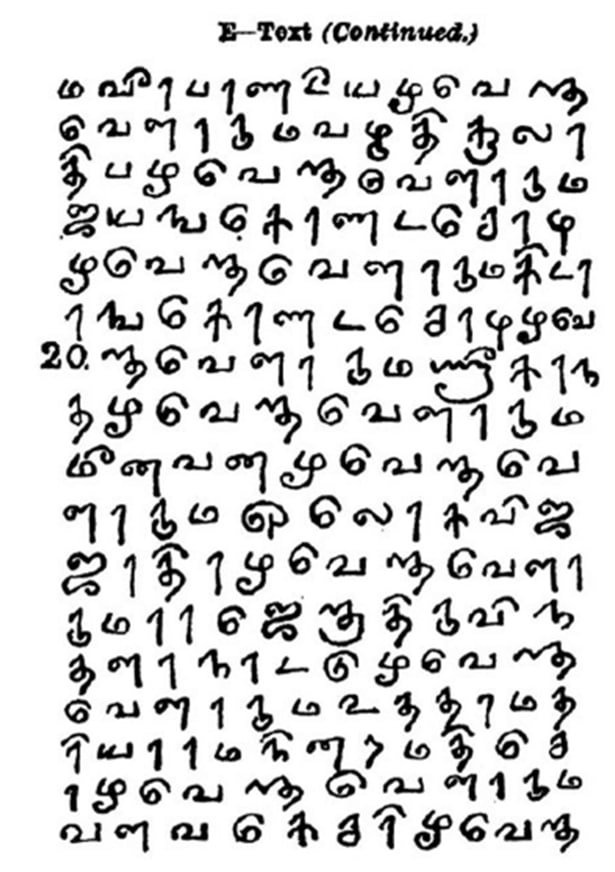

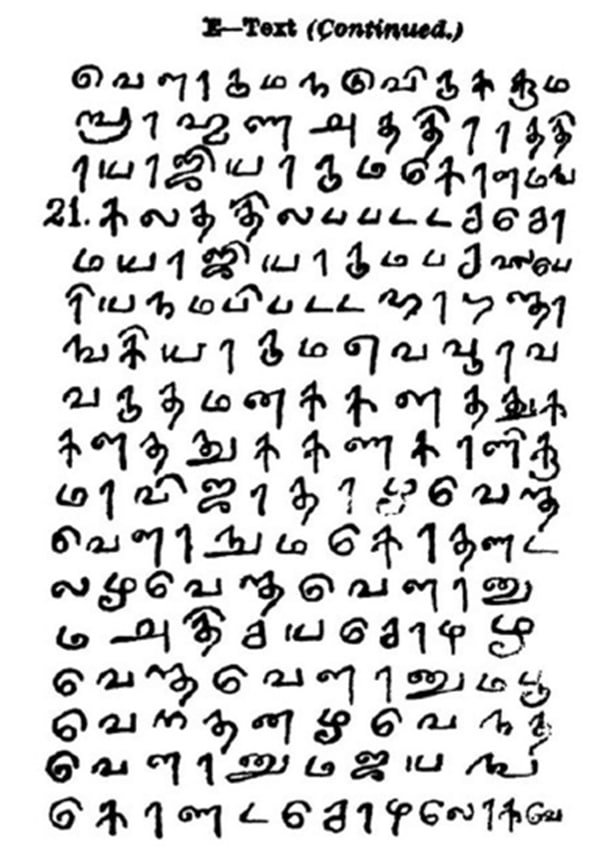

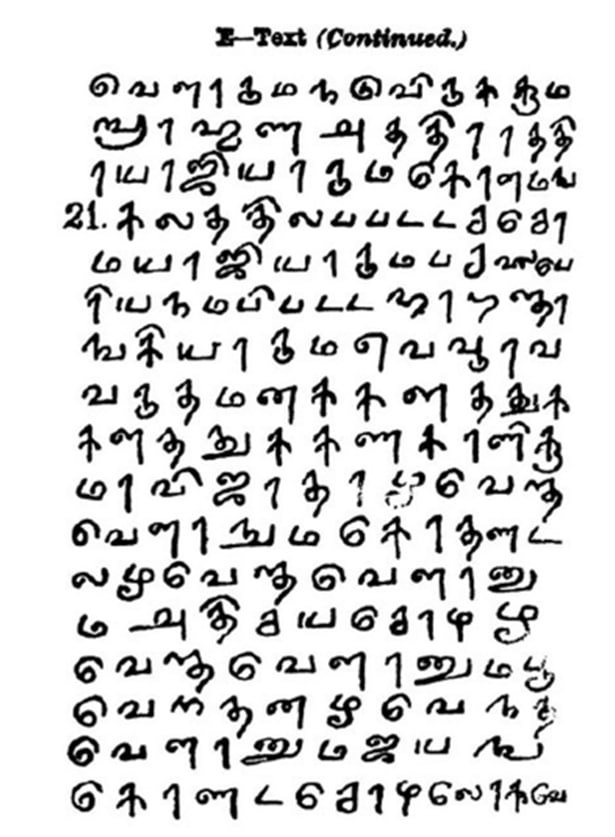

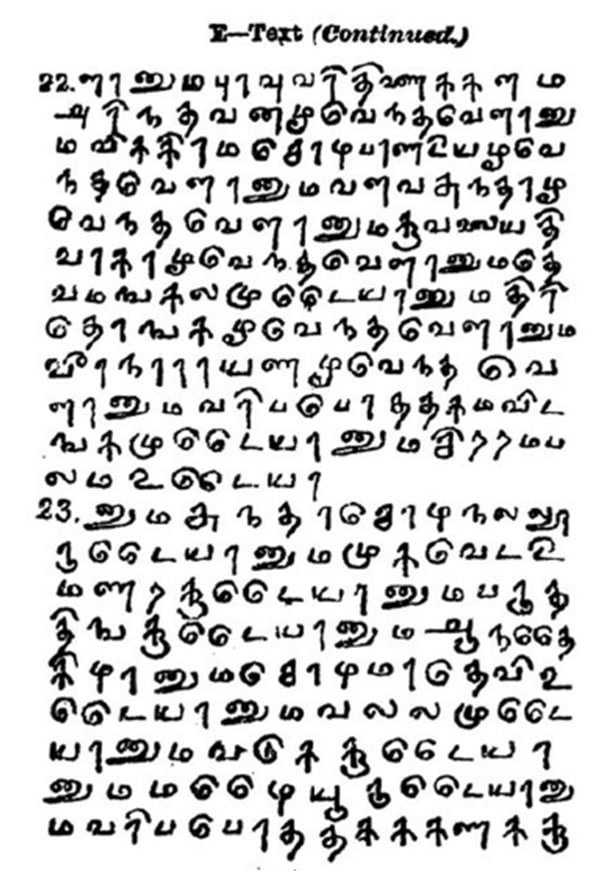

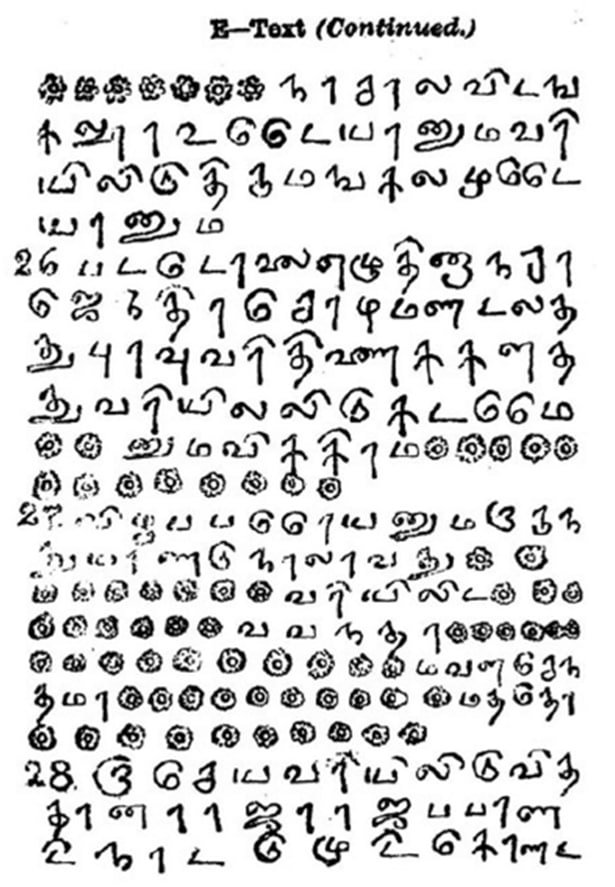

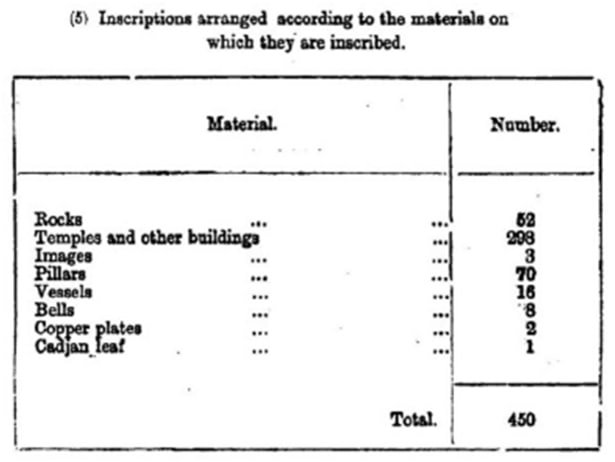

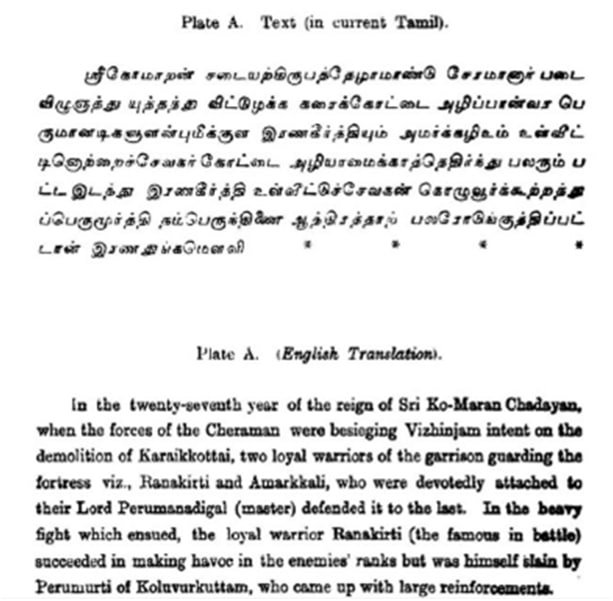

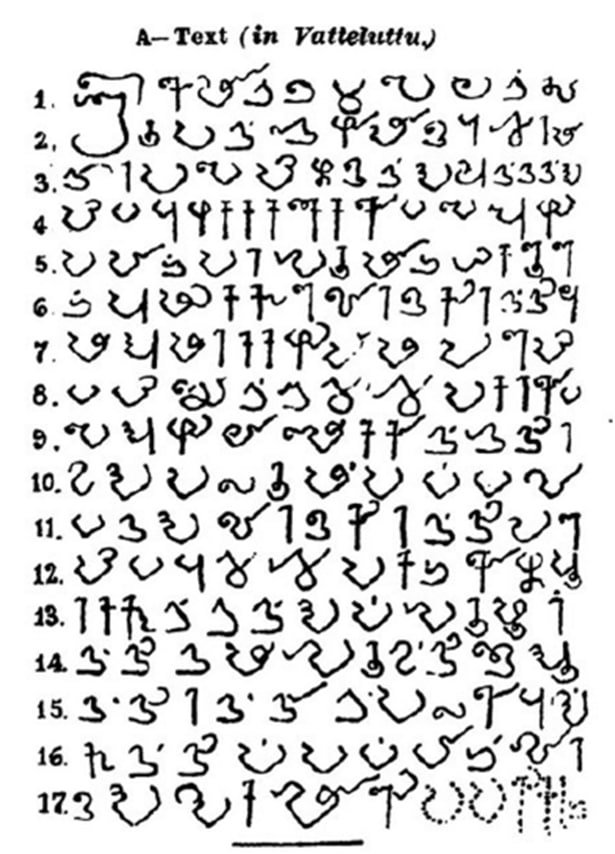

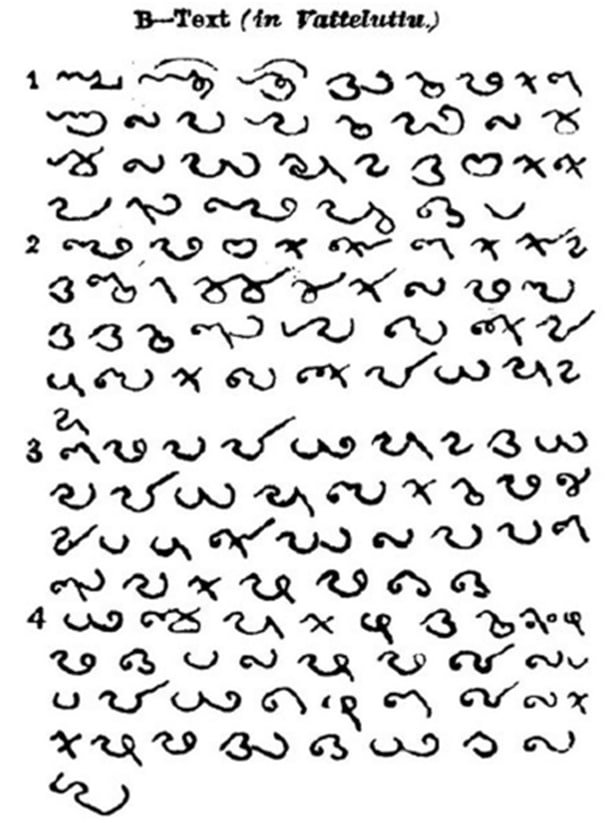

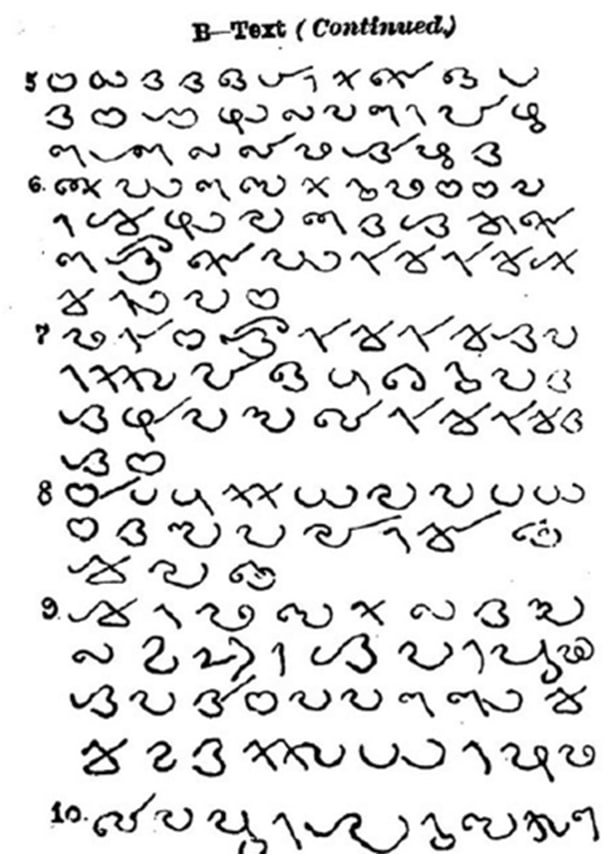

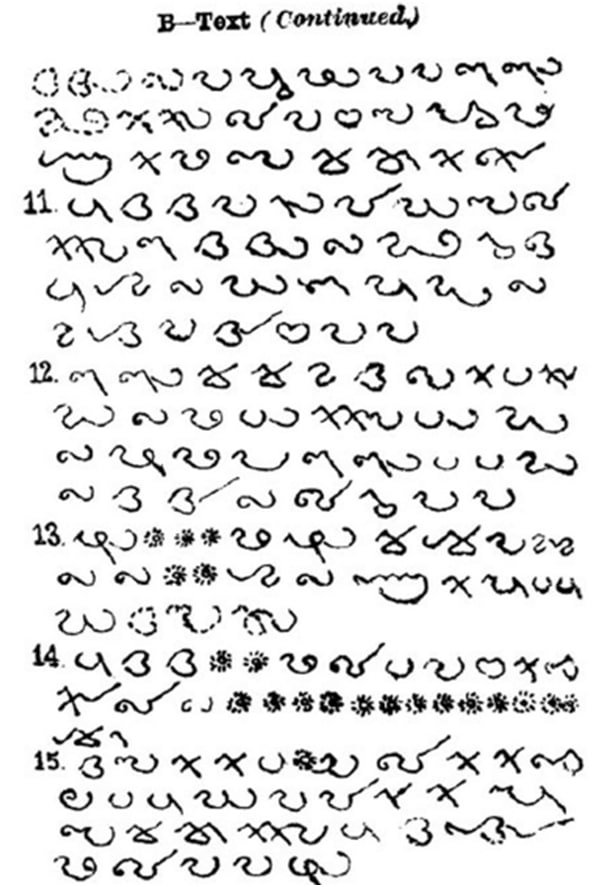

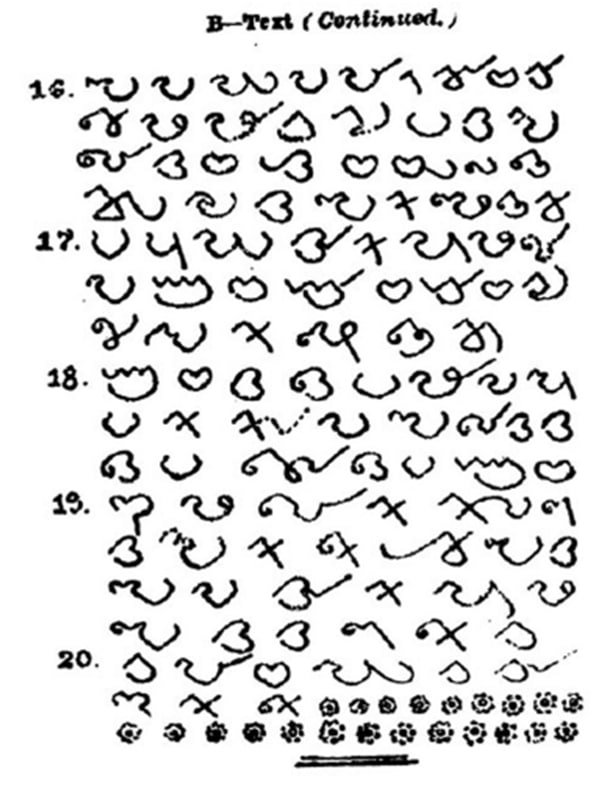

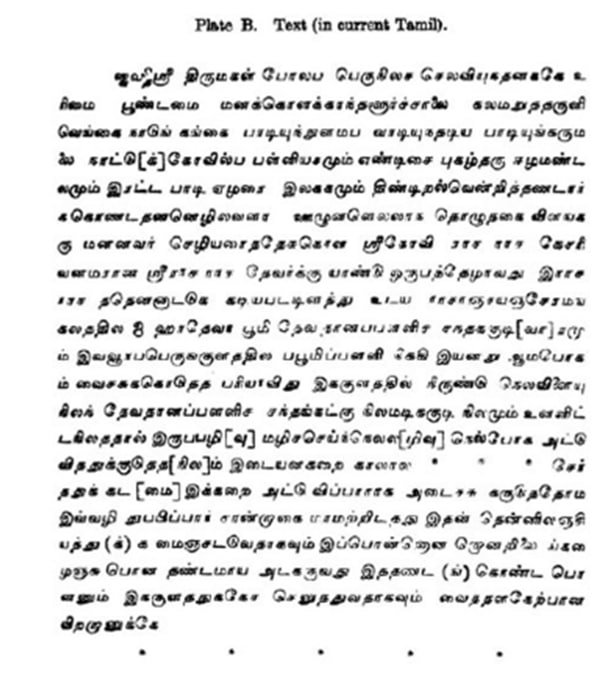

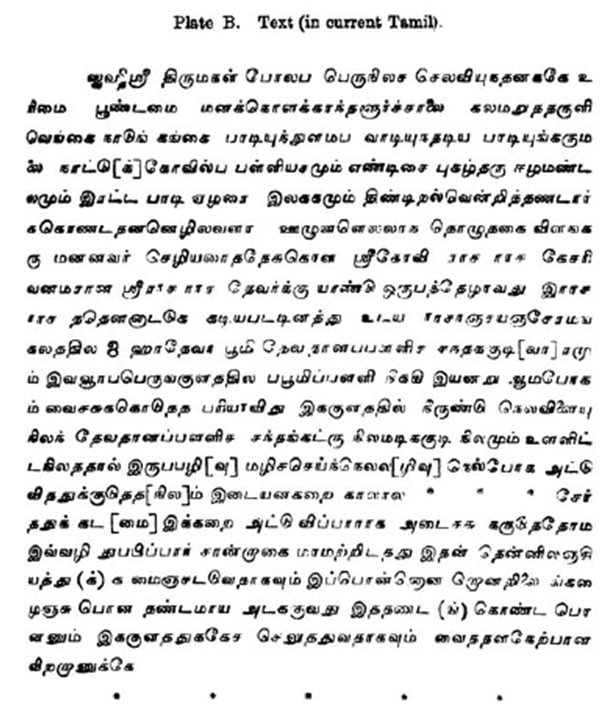

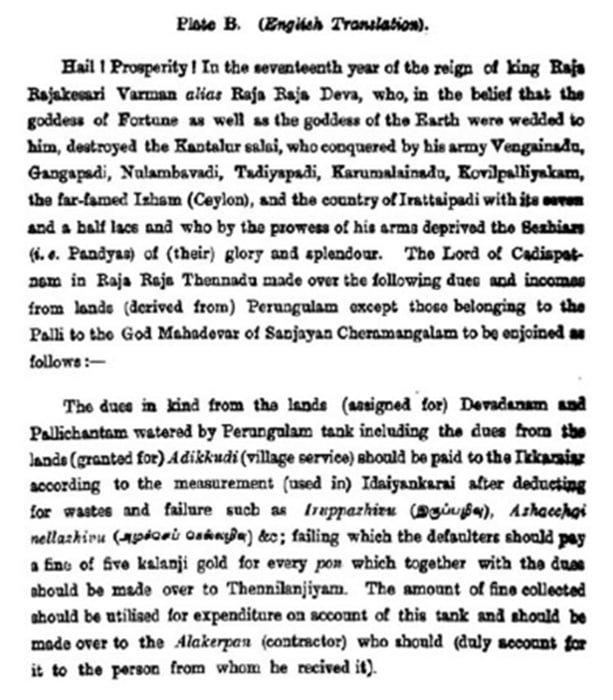

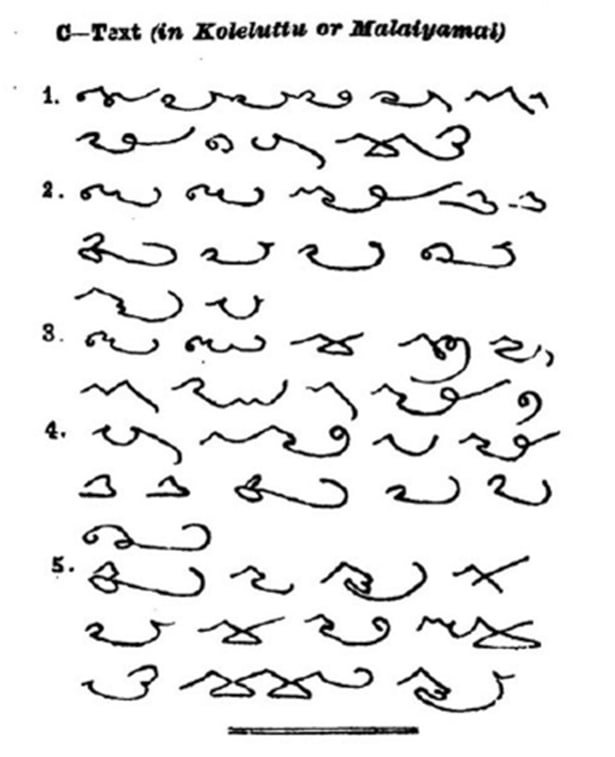

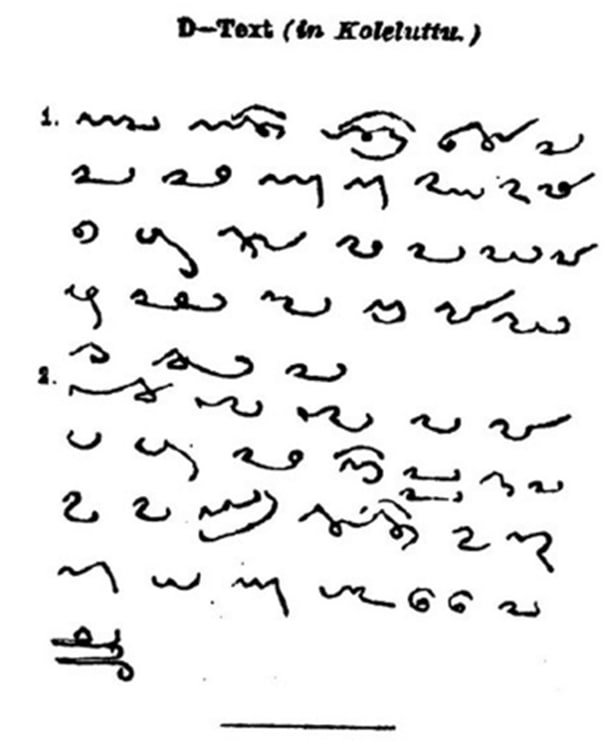

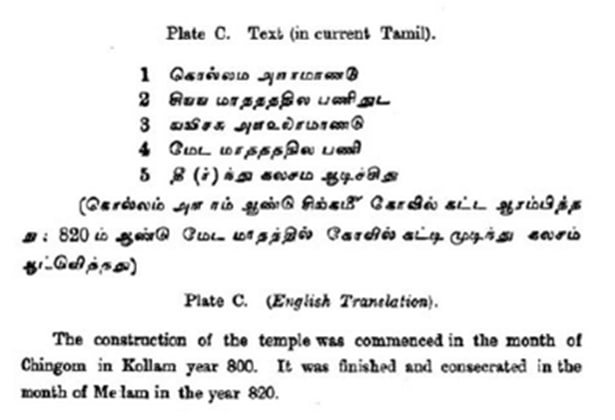

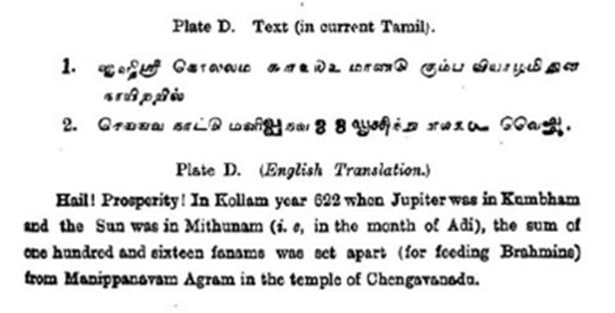

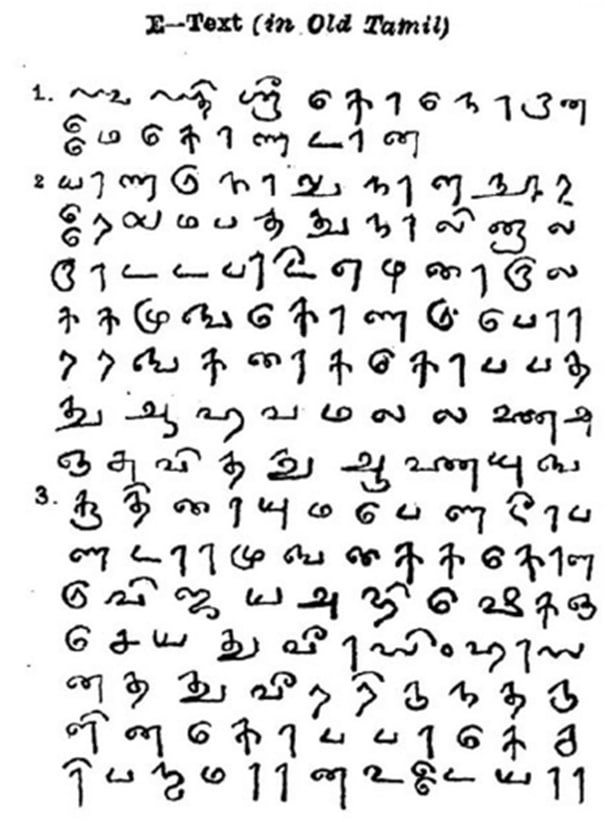

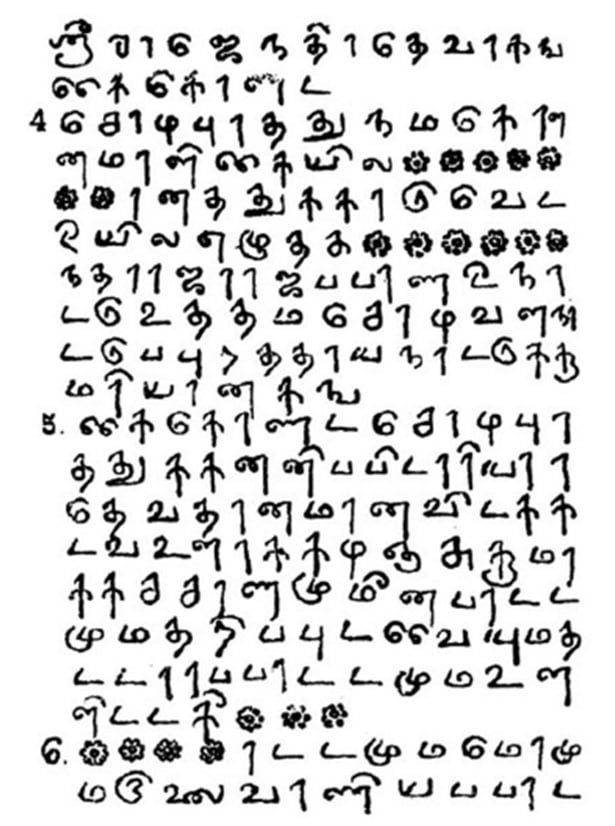

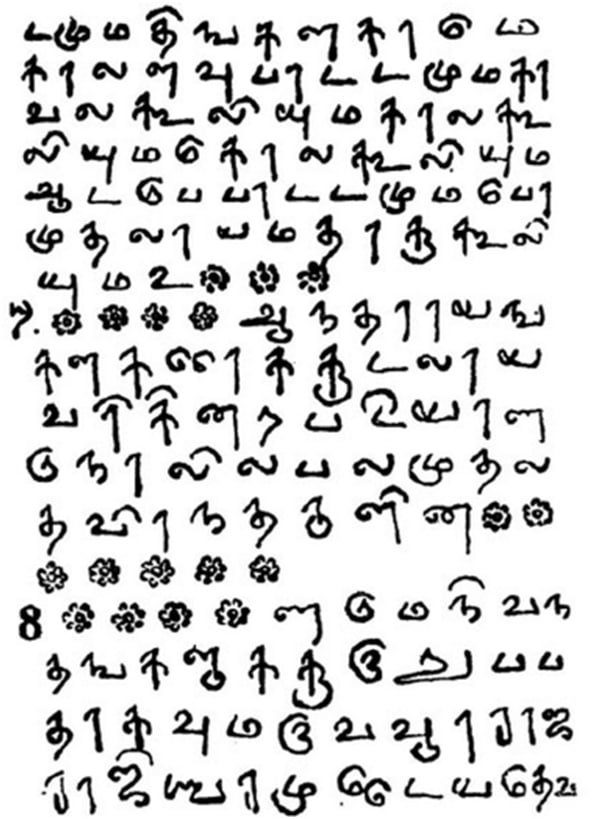

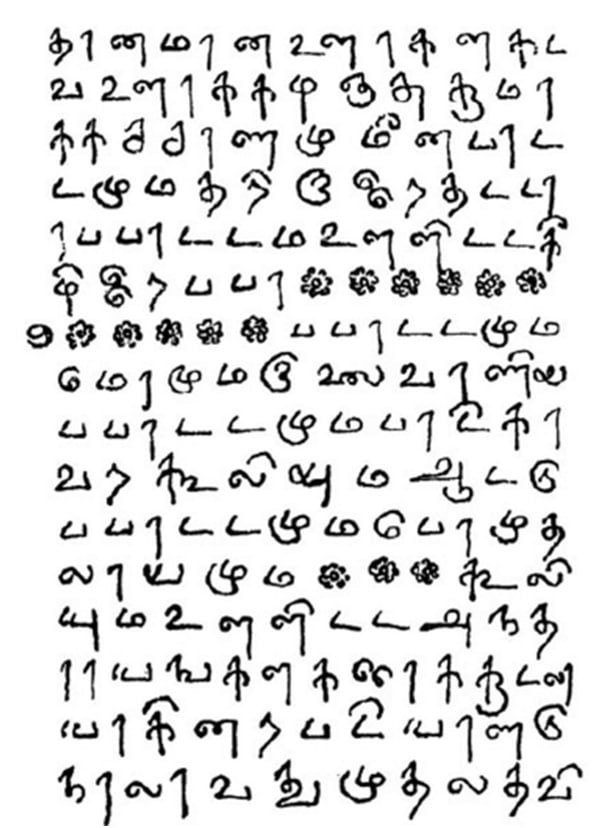

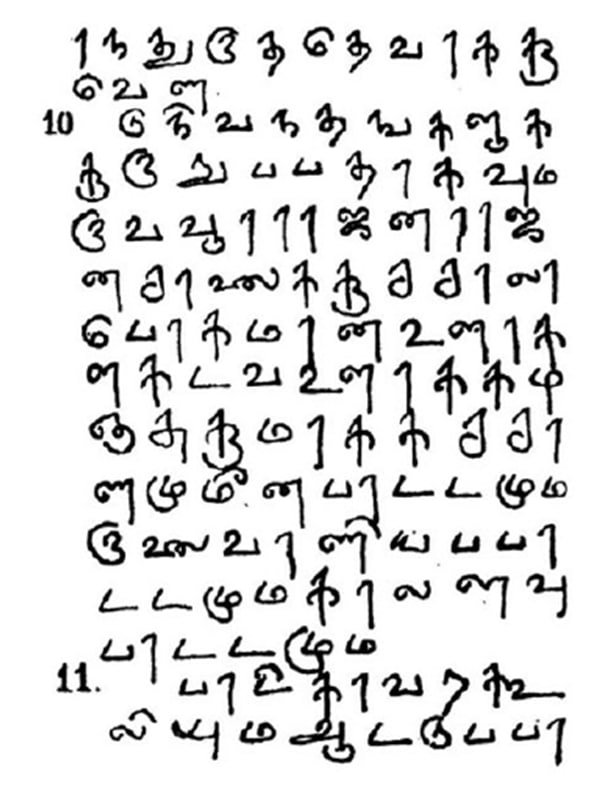

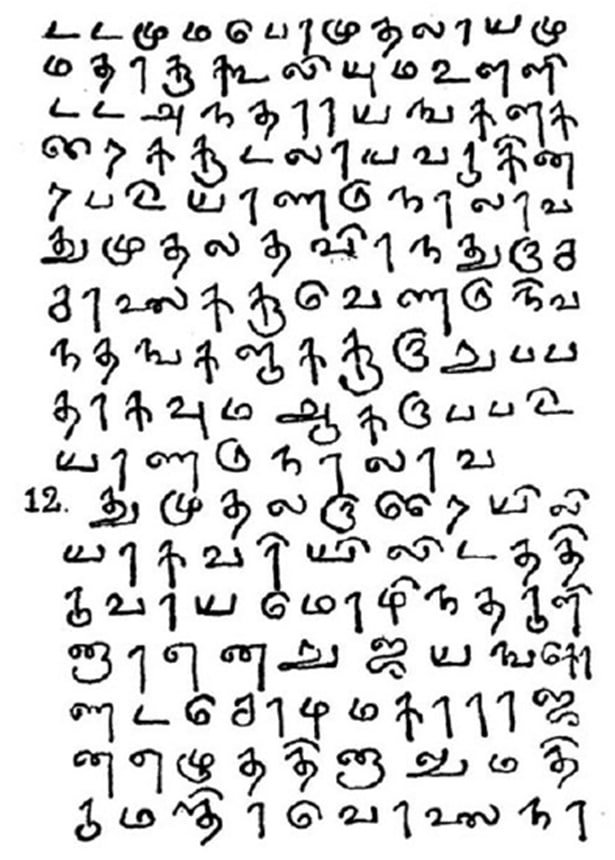

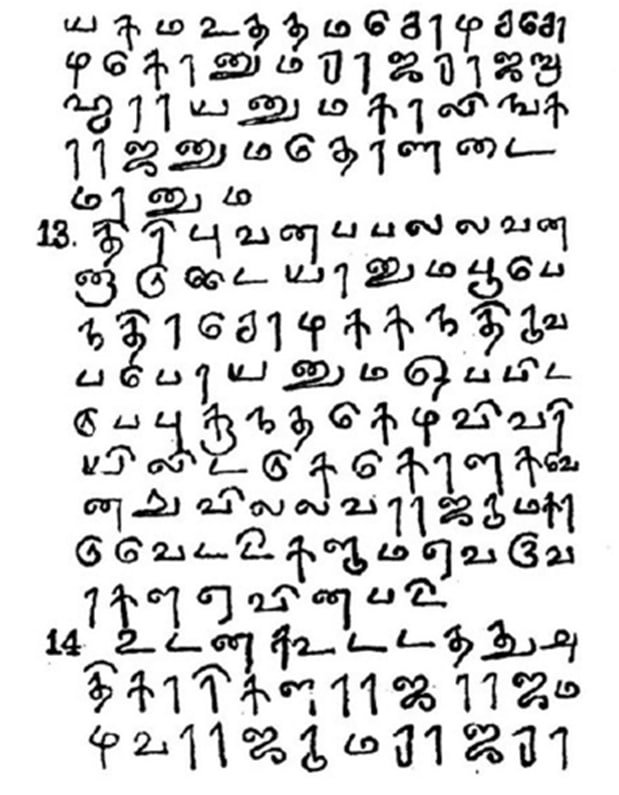

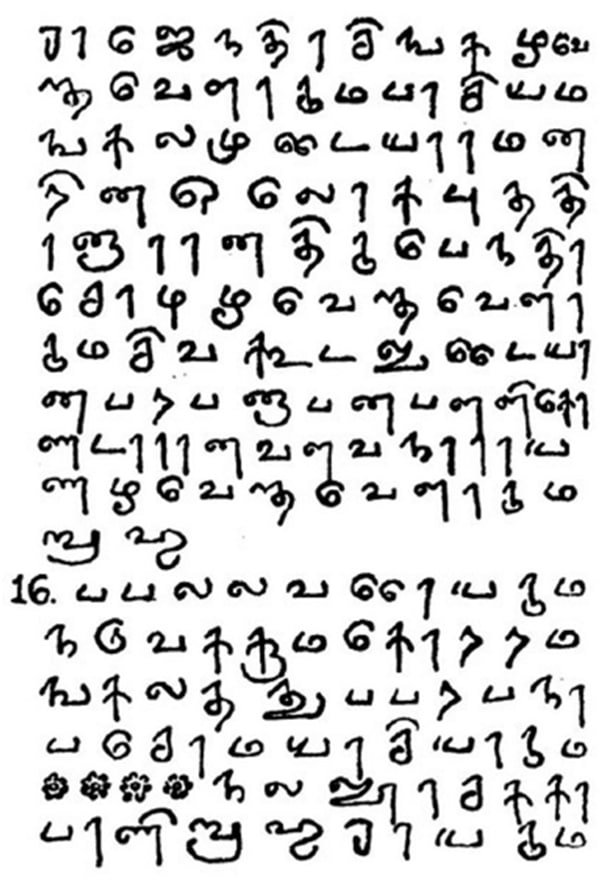

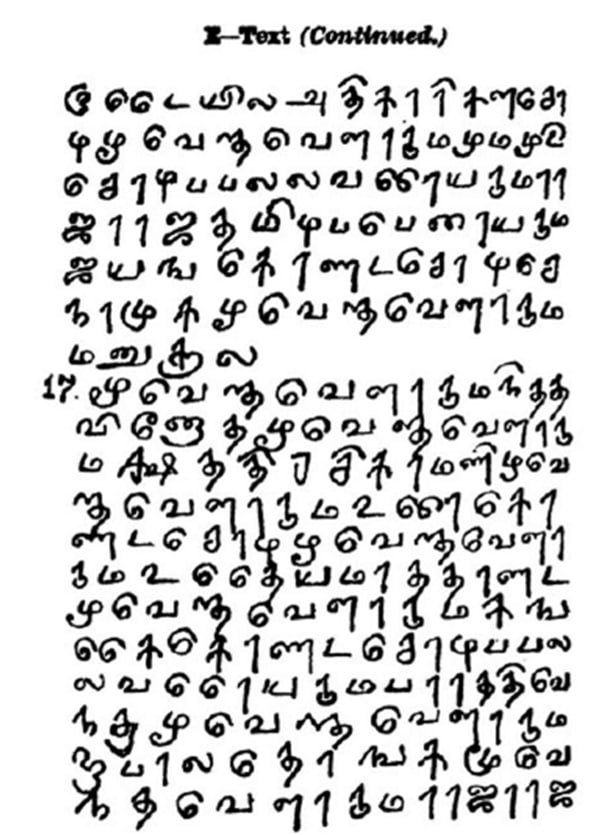

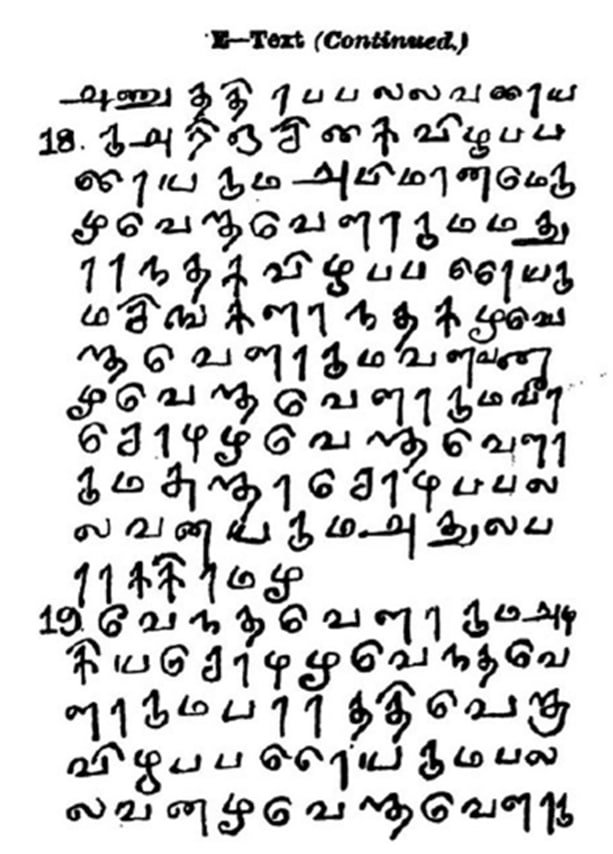

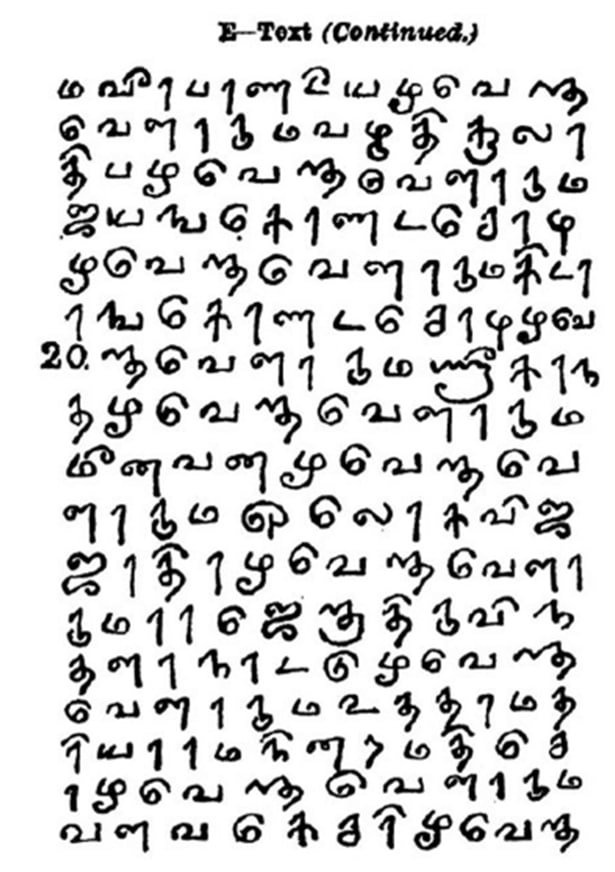

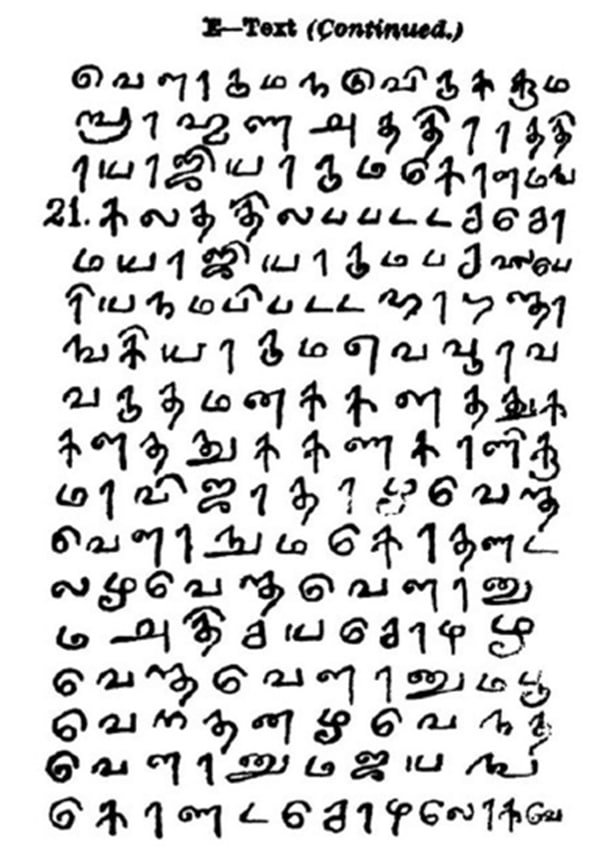

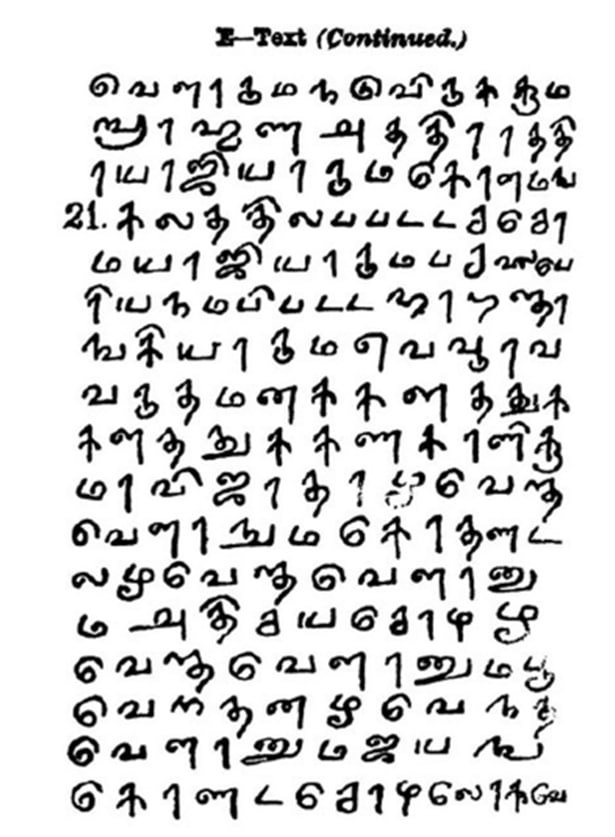

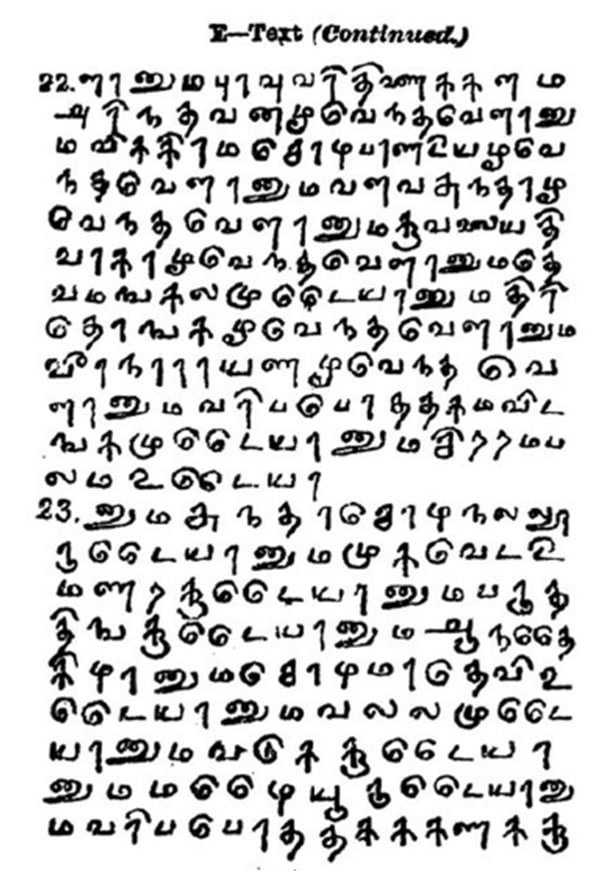

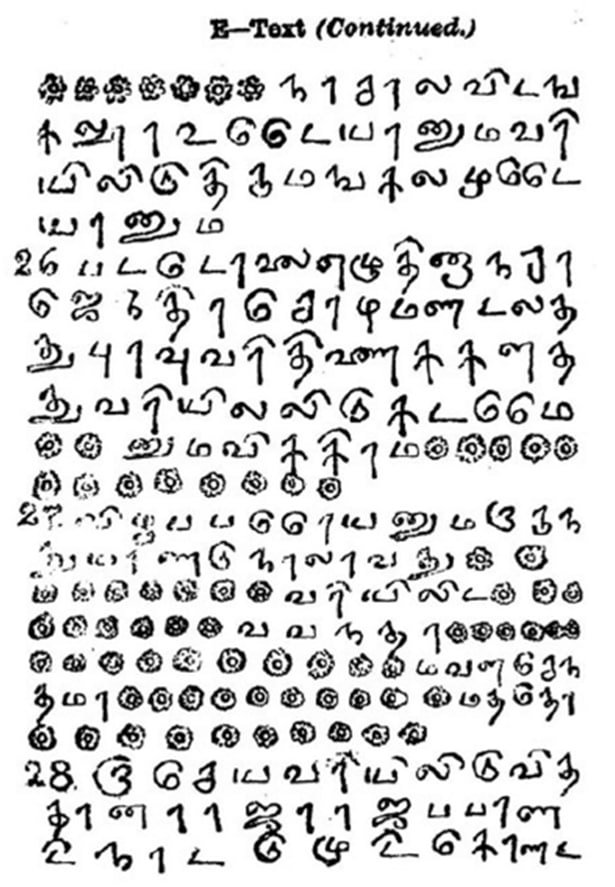

It may be noted that a number of Plates (images) of inscriptions and royal proclamations of Travancore kingdom and nearby areas are given in this book. Not even one is in Malayalam. So much for a language that is claiming Classical Status. Such is the diabolic interest in some persons to get into the positions of Cultural Leadership.

Beyond that current day spoken Malayalam (official version) has an immensity of English words, apart from having a huge number of words which may be actually Sanskrit itself. Apart from that, words from Portuguese, Arabic etc. also may be there. Many technical words have been simply manufactured by specifically appointed persons, leading to an unnecessary confusing array of scientific terminology. Just to satiate the language fanaticism of a particular section of individuals.

1c9 #HOW MUCH TRADE CONTRIBUTES TO CULTURAL ENHANCEMENT

Apart from all this, I have posted the above comparative images of human beings to input another idea. A lot of mention is seen made about international trade in the days of yore. As a person who has done a lot of businesses in various parts of India, it is my observation that trade does not improve the quality of a society. English language does improve the quality. Trade can only improve the quality of the rich classes. It has the negative effect of bringing the lower financial classes to levels of slavery in feudal language nations. In English nations, international trade only allow outsiders the route to enter deep into the English social systems, where they can legitimately set up beachhead. And spoil the native English social systems. Trade in itself is not a positive thing. It can be a dangerous thing. As English nations are slowly getting to comprehend in recent times.

1c10 #MARTHANDA VARMA; an ANGLOPHILE

Now coming to the real beginning of the Travancore as a powerful political entity, it may be presumed that it was King Marthanda Varma who laid its firm foundation. It is mentioned thus:

Martanda Varma, the founder of modern Travancore, succeeded his uncle at the early age of twenty-three.

It may be mentioned that there were a number of rulers in this area in various historical periods having the name Marthanda Varma. However, the king in context here is the ruler of Travancore whose reign was between 1729 and 1758. He was definitely a person with a lot of rare insights. His one wonderful observation was that there was something definitely superior and of refinement in the English East India Company. It was his desire to enter into a very powerful alliance with this entity and get their protection for his kingdom. He who was dauntless in battles, and who had actually defeated a native soldiery force of the Dutch, refrained from any chance for belligerence with the English.

See this quote: A tripartite treaty was entered into and preparations were made to oppose Maphuze Khan, the Maharajah of Travancore contributing four thousand Nayar sepoys.

The two armies met near Calacaud and after a very hot engagement the army of Maphuze Khan was put to flight. But the Travancore army, however, retired home to avoid causing offence to the English Company. Subsequently learning that the English were indifferent, a force was sent under De Lannoy, which defeated Maphuze Khan and recovered Calacaud.

Again there is this quote:

In 1750 A.D. the French attempted to form a settlement at Colachel. It does not appear that they were successful. In the next year the Rajah of Travancore wrote to the King of Colastria ‘advising him not to put any confidence in the French, but to assist the English as much as he could’”.

It was this English East India Company that was to protect the nation of Travancore from foreign enemies. The word ‘foreign’ is used in the sense used in this book. For look at this quote from the earlier part of the book:

Portions of the country now included in the State of Travancore were at various times under the sway of the foreign powers viz.. the Bellalas, Kadambas, Chalukyas, Cholas, Pandyas, Mahomedan rulers (who overran the Pandyan territory), the Zamorin of Calicut and the Rajah of Cochin.

It was this company that secured the independence and freedom of this nation during those semi-civilised days. The term semi-civilised in not mine, for I am sure many jingoist persons would feel offended when the word semi-civilised in used about the ancient and medieval times of the places of the Indian peninsula. See this quote from this book:

for what a rupee secured in those semi-civilised days could not be promptly got for a rupee and a half now.

It was this great Company that brought in peace and prosperity into this land in the Indian peninsula, which was identified by various names, throughout history. See these quotes from this book:

1. “It is the power of the British sword,” as has been well observed, “which secures to the people of India the great blessings of peace and order which were unknown through many weary centuries of turmoil, bloodshed and pillage before the advent of the Briton in India”. [Actually it was not terror of the British sword that held the nation, but the real affection for the English supremacy after 100s years of being slaves to native feudal lords that consolidated the English rule in India. If one were to look back, one can see that if the Indian army is not there in many places like Kashmir, Punjab, Tamilnadu, North East, the current day India would splinter: My words]

2. There is evidence to show that there was perpetual war between Travancore and Vijayanagar lasting for over a century i.e., from 1530 till at least 1635 A.D.

3. ...........but when he has taken some of my people he has been so base to cut off their noses and ears and sent them away disgracefully.

4. It is quite possible that in the never-ending wars of those days between neighbouring powers, Chera, Chola and Pandya Kings might have by turns appointed Viceroys of their own to rule over the different divisions of Chera, one of whom might have stuck to the southernmost portion, called differently at different times, by the names of Mushika-Khandom, Kupa-Khandom, Venad, Tiruppapur, Tiru-adi-desam or Tiruvitancode, at first as an ally or tributary of the senior Cheraman Perumal — titular emperor of the whole of Chera — but subsequently as an independent ruler himself. This is the history of the whole of India during the time of the early Hindu kings or under the Moghul Empire...................

5. ..............collecting their own taxes, building their own forts, levying and drilling their own troops of war, their chief recreation consisting in the plundering of innocent ryots all over the country or molesting their neighbouring Poligars. The same story was repeated throughout all the States under the Great Moghul. In fact never before in the history of India has there been one dominion for the whole of the Indian continent from the Himalayas to the Cape, guided by one policy, owing allegiance to one sovereign-power and animated by one feeling of patriotism to a common country, as has been seen since the consolidation of the British power in India a hundred years ago.

6. As a natural consequence anarchy and confusion in their worst forms stalked the land. The neighbouring chiefs came with armed marauders and committed dacoities from time to time plundering the people wholesale, not sparing even the tali* on their necks and the jewels on the ears of women. The headman of each village in his turn similarly treated his inferiors. The people of Nanjanad in a body fled to the adjoining hills on more than two occasions, complaining bitterly to the king of his ineffetiveness and their own helplessness.

7. While Hyder was thus attempting an entry into Travancore, his own dominions in the north and east were invaded by the Nizam, the Mahrattas and the English. He therefore abandoned his attempt on Malabar and made haste to meet the opposing armies. ..........................................About 1769, Hyder was defeated by the East India Company’s soldiers in several engagements. This convinced him of the existence of a mightier power in South India and tended to sober his arrogance and cruelty.

8. Then there is the dying words of King Rama Rajah, the Dharma Rajah, who died on a believed to be inauspicious day. The barbarianism of wars, all wars is clear in them. Imagine a land that moves one war to another, with regular periodicity.

QUOTE:

“Yes I know that to-day is Chuturdasi, but it is unavoidable considering the sins of war I have committed with Rama Iyan when we both conquered and annexed several petty States to Travancore. Going to hell is unavoidable under the circumstances. I can never forget the horrors to which we have been parties during those wars. How then do you expect me to die on a better day than Chaturdasi? May God forgive me all my sins”

Somehow Marthanda Varma could discern that the English traders were quite different from others, including the people from his own land. Why it was so may not have been clear to him. However, the answer lies in the fact that the English men talked and thought in the English language, which was quite different from most other tongues in that there was no feudal, hierarchical, people splitting, pejorative versus respect codes in ordinary and formal conversation.

For making this idea clear, I am giving here the translation of a single sentenc in English: Where are you going?

This sentence can be translated into the following sentences in Malayalam, all meaning the same when viewed from English. However, there is a range of movement of individuals along a vertical as well as horizontal path, as well as the trignometic components, when the different sentences in Malayalam are taken up for use.

1. Nee yevideyaanu pokunnathu? നീയെവിടെയാണ് പോകുന്നത്?

2. Nee yevideyaada pokunnathu? നീയെവിടെയാടാ പോകുന്നത്?

3. Nee yevideyaadi pokunnathu?

നീയെവിടെയാടീ പോകുന്നത്?

4. Yeyaal yevideyaanu pokunnathu?

ഇയാൾ എവിടെയാണ് പോകുന്നത്?

5. Thaan yevideyaanu pokunnathu?

താൻ എവിടെയാണ് പോകുന്നത്?

6. Ningal yevideyaanu pokunnathu?

നിങ്ങൾ എവിടെയാണ് പോകുന്നത്?

7. Thaangal yevideyaanu pokunnathu?

താങ്കൾ എവിടെയാണ് പോകുന്നത്?

8. Saar yevideyaanu pokunnathu?

സാർ എവിടെയാണ് പോകുന്നത്?

9. Maadam yevideyaanu pokunnathu?

മാഢം എവിടെയാണ് പോകുന്നത്?

10. Chettan yevideyaanu pokunnathu? ചേട്ടനെവിടെയാണ് പോകുന്നത്?

11. Chechi yevideyaanu pokunnathu?

ചേച്ചി എവിടെയാണ് പോകുന്നത്?

12. Ammaavan yevideyaanu pokunnathu?

അമ്മാവൻ എവിടെയാണ് പോകുന്നത്?

13. Ammaayi yevideyaanu pokunnathu?

അമ്മായി എവിടെയാണ് പോകുന്നത്?

For knowing more about feudal, hierarchial languages, please read my books:

1. The Shrouded Satanism in Feudal Languages; Intractability and Tribulations of Improving Others.

2. March of the Evil Empires; English versus the Feudal Languages

3. Codes of reality! What is language?

4. An impressionistic history of the South Asian Peninsula

Marthanda Varma’s love for the English people can be seen from his last advice and instruction to his heir and nephew Prince Rama Varma, on his deathbed.

Marthanda Varma’s words: “That, above all, the friendship existing between the English East India Company and Travancore should be maintained at any risk, and that full confidence should always be placed in the support and aid of that honourable association.” –

See these quotes also:

:

1. He (Hyder Ali) then turned to the King of Travancore and demanded of him fifteen lacs of rupees and twenty elephants threatening him with an immediate invasion of his territories in case of refusal. The Cochin Rajah now placed himself unreservedly under the protection of the Dutch, but the Travancore Maharajah feeling strongly assured of the support of the English East India Company replied, “that he was unaware that Hyder went to war to please him, or in accordance with his advice, and was consequently unable to see the justice of his contributing towards his expenses”

2. The Travancore sepoys sent to garrison the Ayacotta fort retreated in expectation of attack by the Mysore troops but on the timely arrival of a Dutch reinforcement the Mysoreans themselves had to retire.

3. In the war that followed, the Travancore sepoys fought side by side with the English at Calicut, Palghat, Tinnevelly and other places.

4. “.....I am well informed how steady and sincere an ally Your Majesty has ever been to the English nation. I will relate to the Governor-in-Council the great friendship you have shown and the services you have rendered to the English interests in general and to the army that I commanded in particular.”

5. Hudleston assured the Rajah on behalf of the ‘Company, “Your interests and welfare will always be considered and protected as their own,” and added, “the Company did not on this occasion forget your fidelity and the steady friendship and attachment you have uniformly shown them in every situation and under every change of fortune”.

6. But he (Tippu) could not make bold to appear as principal in the war, for the Travancore Rajah had been included in the Mangalore treaty as one of the special “friends and allies” of the Honourable Company.

7. The Travancore Rajah replied that he could do nothing without the knowledge of his friends and allies, the English and the Nawab. The matter was soon communicated to the Madras Government who sent Major Bannerman to advise the Rajah.

8. The Governor informed Tippu that aggression against Travancore would be viewed as a violation of the Treaty of 1784 and equivalent to a declaration of war against the English.

9. Later on, as we shall see, it was due to Lord Cornwallis’ firmness and decisive action that Travancore was saved from falling an easy prey into Tippu’s hands.

10. The subsequent inaction of the Government of Mr. Holland roused his anger to such an extent as to accuse them of “a most criminal disobedience of the clear and explicit orders of the Government dated the 29th of August and 13th of November, by not considering themselves to be at war with Tippu from the moment that they heard of his attack” on the Travancore lines.

11. “Secure under the aegis of the British Queen from external violence, it is our pleasant, and, if rightly understood, by no means difficult task to develop prosperity and to multiply the triumphs of peace in our territories. Nor are the Native States left to pursue this task in the dark, alone and unaided

This was a friendship that stood the test of time, even though there were times when it was severely tested. It lasted till a fool came to power in England as the Prime Minister of Britain. He made a mess of everything that had been built up over the centuries by ordinary English folks, (not academicians) all over the world, with total participation of the common man in the far-flung areas.

When speaking about the life and times of Marthanda Varma, there are these things that come out. One very visible feature about his life is the parade of hair-breath escapes he has had from the attacks by his enemies.

The basic issue seen here is that the King’s children did not inherit the throne. Only his sister’s children were entitled to it. Even though this may seem quite a strange family tradition, when looking back from these so-called modern times, a very powerful reason is mentioned. It is connected to the general sexual customs of the times, connected to the Matriarchal family system. The females were given the freedom to sleep with a variety of personages of higher social class and caste. The females from the King’s family had such links with certain households. At the same time, the Brahmin males could sleep with the Nair (Shudra) females. It was not seen as an imposition, but as a great privilege to be such entertained by the Brahminical classes.

See these quotes:

1. “The heirs of these kings are their brothers, or nephews, sons of their sisters, because they hold those to be their true successors, and because they know that they were born from the body of their sisters. These do not marry, nor have fixed husbands, and are very free and at liberty in doing what they please with themselves.”

2. These young men who do not marry, nor can marry, sleep with the wives of the nobles, and these women hold it as a great honour, because they are Bramans, and no woman refuses them.

The fact is that this problem of certitude of bloodline in the children of the sisters, and the uncertainty of the bloodline of the father in his wife’s children was there in almost all castes that did follow the matriarchal system. This included the Nairs as well as the North Malabar Thiyyas. [South Malabar Thiyyas were of a different breed and customs].

When Marthanda Varma ultimately crushed his enemy side, the Ettuvettil Pillamars [in the melee, his own uncle’s, (the former king’s) sons were also killed by him or by his side], there was a certain streak of social barbarity that was enacted.

See this quote:

..........women and children were to be sold to the fishermen of the coast as slaves.

This barbarity is something the native English speakers will never understand. They stand like fools declaiming a foolish history that slavery had been practised in the English nation of USA. Actually what took place in USA was not slavery. Rather it was a brief period (75 years) of social enrichment programme given freely to people who had been enslaved in their own nation and sold into a newly emerging nation, where the majority were English speakers. They were the lucky black slaves. The unlucky black slaves were sold to African, Asian, Arab, South American and other-area slave masters.

The females sold by Marthanda Varma as slaves to the fishermen folks were actually of same social status of the females who later became the queens of Travancore. See these pictures.

To be sold as slaves to different levels of people is the issue here. If they had been sold as personal slaves to the Rajahs, the degradation wouldn’t be much. However, the degradation increases exponentially as the slave master class’ level goes down. For, the languages of the Indian peninsula are feudal, hierarchal and have the codes of pejoratives versus that of ‘respect’. Such words a What is your name? What is it? Edi, She, You, etc. when mentioned in the local vernacular could have different levels of impact depending on the levels of the persons who dominate. To be addressed as Nee, Edi, Alae, and mentioned as Aval (Oal).by persons who have been kept as the lower, dirt level classes by the vernacular can have deep physical and mental impacts, which can literally terrorise a person into stinking dirt.

See this quote:

1. In despair, therefore, their chiefs resolved upon marshalling a large number of foreign Brahmin settlers in the vanguard of their fighting men to deter the Maharajah’s forces from action, as they would naturally dislike the killing of Brahmins, Brahmahatti or Brahminicide being the most heinous of sins according to the Hindu Shastras. The Dalawa however ordered firing, but his men would not. Then he ordered a body of fishermen to attack the Brahmins who, at the sight of their low caste adversaries, took to flight.

2. Hyder adopted very stringent measures to subdue the refractory Nayar chiefs. He first deprived them of all their privileges and ordered that they should be degraded to the lowest of all the castes.

Modern policymakers do not understand the basic code that works here. Fighting with the British and the US soldiery is something that is worth mentioning. Even a losing can be mentioned. To fight with a low class group is not a great thing. A losing to them, is a terrible losing.

It would be like a young IPS officer being addressed as Nee (Inhi), and referred to as Avan (oan), Aval (oal), Mone, Mole etc. by a senior-in-age constable in a very affectionate tone. This affection would be a murderous one.

1c11 #WHEN SLAVERY ACTUALLY was LIBERATION

To be sold as slaves to the English speaking races would actually be an act of liberation for many of the lower caste peoples of earlier age Indian peninsula and Africa. Even though the children of the black slaves who had the luck to be sold as slaves in a newly emerging English nation wouldn’t admit it. And the foolish native English speakers wouldn’t know that they are actually liberating the blacks through their ‘slavery’. And that too an ungrateful crowd.

It is like this. The English side gave them the learning to sit in a chair, dress up like themselves, address them by name, eat their own type of food, gave them entry into their own religion, liberated them from the traumatising social behaviour of having to ‘respect’ their master class in each and every word, deed, and physical postures. Above all taught them English, the language that can change person from the filth of barbarianism to that of human dignity. It is like this: a woman who is addressed thus in Malabar language: Yenthale? by a lower class female, will feel and display the shivers of dirtying social positioning. It is not a wrong usage or a profanity, and not even like calling a black man a nigger. It is a perfectly justifiable Malabar word. Yet, it can have a very powerful negative impact.

From the English side came the English classical literature, which if read and imbibed, could embed the codes of human dignity and civility to the reader and his society. What was there for the Blacks to give in return? Just brute physical power, with which they were allowed to displace the native English speakers from most physical arenas. Only a few of them really took up the aim to focus on the finer elements of what was on offer from the English side. For, their innate focus was on the use of physical superiority on the females of the other side. The moral standards of the Victorian Age that had permeated into the New World lay waste as the land was allowed to be occupied by outsiders who had no sense of obligation.

1c12 #RAMA VARMA

When Marthanda Varma died, his nephew Rama Varma ruled the nation in perfect alignment to what his uncle had advised him. To maintain the good will of the English East Indian Company. This was to bring in security, prosperity and stability to the royal family.

See this quote:

The King of Travancore also sent a strong force to co-operate with the English at Trichinopoly. Issoof Khan was captured and hanged at Maura as a public enemy in 1766.

The great security was the feeling that there was a supreme power in South Asian peninsula which was duty bound to maintain peace in the geographical area. To see a sample of what this terror of war meant, see this quote:

.........but when he has taken some of my people he has been so base to cut off their noses and ears and sent them away disgracefully.

1c13 #AN ANTEDATING

The periodic raids in which the undisciplined soldiery and their masters would pounce upon females not only for the jewellery they wore, but for other lavish entertainments in a feudal vernacular ambience, was a regular feature. This has the same quality degradation as of being enslaved under the socially designated lower classes. There was actually a time when the people did revolt against the King in Travancore, when they were thus exposed to the periodic raids by outsiders. No family could maintain their relationships intact, when such raider came regularly to have their feast upon the females at will. And the king was not able to protect them. The people joined together and more or less proclaimed something which may be called a Declaration of Independence more or less similar to what was done by a few idiots in the USA, when they revolted against ‘taxation’ without ‘representation’. Actually they did not have even a single ounce of grievance comparable to what the people of Nanjangad did suffer from. All they had was arrogance. See what happened in Nanjangad.

.........sent a large army under the command of Narasappayya the Madura Dalawa. He invaded the country, conquered the Travancore forces after hard fighting and returned to Trichinopoly with considerable booty consisting of spices, jewels and guns. The attacks from Madura for collecting the arrears of tribute from the Travancore king became more frequent while the efforts of the latter to resist them seemed to be futile. The Nanjanad people, who had to bear the brunt of these frequent attacks, became naturally very callous to pay their homage and allegiance to their sovereign who was not able to protect them from his enemies.

The people of Nanjangad united and made proclamations. See this quote:

The discontent of the people developed into open revolt and the Nanjanadians are said to have convened five meetings in different places from 1702 A.D., forward. .

On going through their proclamations as seen in inscriptions, it is clear that the American Declaration of Independence was only a minor copying of what was mentioned in Travancore by the people there. However, these people did not have English, which would have united them and given them power, and the adequate communication machinery to work out the grievance more intelligently. They only had feudal vernaculars which have the codes of society-splitting embedded in them. The ungrateful wretches in the American states had English, and in their heights of ingratitude and insanity, they wanted to fight against the very nation that had bequeathed them ‘English’, human liberty, human dignity, civic manners, words of polite interaction, historical experience, experiences in administration, writing, learning, English literature and much else.

1c14 #NAYAR PADA [Nayar Brigade]

There is the mention of the Nayar pada, which was later, much later recreated as the Nayar Brigade under English officers. However, the beginnings of the English military systems were actually given by a Dutch military officer. Name: De Lannoy. He was a war prisoner of Marthanda Varma, who was asked by the king to create military wing on European (meaning Dutch/English) lines. See this quote:

The first, De Lannoy, commonly known in Travancore as the Valia Kappithan (Great Captain) was in the manner of an experiment entrusted with the organisation and drilling of a special regiment of sepoys this he did very successfully and to the satisfaction of the Maharajah. Several heroic stories are extant of the achievements of this particular regiment. De Lannoy was next made a Captain and entrusted with the construction of forts and the organisation of magazines and arsenals. He reorganised the whole army and disciplined it on European models, gave it a smart appearance and raised its efficiency to a very high order.

The difference it made is here in this quote:

Kayangulam Rajah had anticipated the fate of his army. He knew that his ill-trained Nayars were no match to the Travancore forces which had the advantage of European discipline and superior arms.

See these quotes also:

1. Harold S. Ferguson Esq.................then as Commandant of one of the battalions in the Travancore army (Nayar Brigade)

2. The armies of the chieftains consisted of Madampis (big landlords) and Nayars who were more a rabble of the cowardly proletariat than well-disciplined fighting men.

3. But Rodriguez not minding raised one wall and apprehending a fight the next day mounted two of his big guns. The sight of these guns frightened the Nayars and they retreated; the Moplahs too lost courage and looked on. The work of building the fort was vigorously pushed on even in the rainy season, and the whole fortress was completed by September 1519 A.D., and christened Fort Thomas.

4. [In this quote, you will see that De Lannoy, the Dutch man commanded the Travancore forces to attack the Dutch fort. On the Dutch side, it was the Nayars who fought.] Several battles were fought against the combined forces of the Kayangulam Rajah and the Dutch whose alliance gave the former fresh hopes. Much perseverance, stubbornness and heroism were displayed on both sides. Six thousand men of the Travancore army attacked the Dutch fort at Quilon which was gallantly defended by the Nayars commanded by one Achyuta Variyar, a Kariyakar of the Kayangulam Rajah.

5. The whole force was composed of Nayars, Sikhs, and Pathans under the supreme command of De Lannoy.

6. To effect economy in the military expenditure, Velu Tampi proposed a reduction of the allowances to the Nayar troops and in this he was cordially supported by the Resident. The proposal caused great discontent among the sepoys. They resolved on the subversion of the British power and influence in Travancore and the assassination both of the Dewan and the British Resident.

7. [This is with regard to Velu Tampi’s takeover attempt] Meanwhile the subsidiary force at Quilon was engaged in several actions with the Nayar troops. But as soon as they heard of the fall of the Aramboly lines, the Nayars losing all hopes of success dispersed in various directions.

8. After the death of Velu Tampi the rebels continued in arms here and there in parts of the Quilon district, but the arrival of the English forces soon brought them to their senses and order was quickly restored................... The Carnatic Brigade and some Nayar battalions were dismissed and the defence of the State was solely entrusted to the subsidiary force stationed at Quilon,

9. After the revolt of Velu Tampi in 1809, there was practically no army in Travancore. (Col) Munro organised two battalions of Nayar sepoys and one company of cavalry as “bodyguard and escort to Royalty”. ..............European officers were appointed to the command of this small force.

10. The Nayar Brigade. After the insurrection of 1809 the whole military force of Travancore was disbanded with the exception of about 700 men of the first Nayar battalion and a few mounted troops, who were retained for purposes of state and ceremony. In 1817 the Rani represented to the Resident Col. Munro her desire to increase the strength and efficiency of the army and to have it commanded by a European officer, as the existing force was of little use being undisciplined and un-provided with arms. On the strong recommendation of the Resident, the proposal was duly sanctioned by the Madras Government in 1818, and the Rani was given permission to increase her force by 1,200 men........................ Thus was organised the present Nayar Brigade, though the designation itself was given to it only in 1830 A.D.

11. The visit of His Excellency the Governor gave the Maharajah an opportunity to see the British forces in full parade. He was struck with their dress and drill and made arrangements for the improvement of his own forces after the British model. New accoutrements wore ordered and the commanding officer was asked to train the sepoys after the model of the British troops. The dress of the mounted troopers was improved and fresh horses were got down; and the appellation of the “Nayar Brigade” was first given to the Travancore forces. The Tovala stables were removed to Trivandrum and improved. On the advice of the Court of Directors, the European officers of the Nayar Brigade were relieved from attendance at the Hindu religious ceremonies.

12. A scheme for placing a portion of the Nayar Brigade on a more efficient footing was sanctioned in 1076 M.E (1900-1901) and came into operation in the next year. The two battalions that hitherto existed were amalgamated the sixteen companies were reduced to ten with a strength of 910 of all ranks. This reduction provided 500 men for the new battalion, which was styled the First Battalion and is intended for purely military duties following as far as possible the economy and discipline of the British Native Infantry.

This much is mentioned here, just because the Nair Brigade is often mentioned as a proof that the Nairs belong to the Kshatriya caste. However, the fact is that in contemporary times, in Malabar Thiyyas (a lower castes) were in the British-Indian army. At least one person I am aware was even a commissioned officer in the Royal Air Force. It does not mean that Thiyyas are Kshatriyas

1c15 #KESAVADASAPURAM

When one goes to Trivandrum, it is possible that one moves through Keshavadasapuram. Well, this Keshava Das must have been the Dewan of Rama Varma.

1c16 #A FAKE HISTORY NOT MENTIONED

Now there is one fantastic thing that could be noticed. In the history part, a lot of discussions are there about the various kingdoms of south India and also of north India. Even minor kings and kingdoms are discussed. However, there is very negligible mention of a ‘Kottayam Raja’ who ruled over the ‘great’ Kottayam village near Tellicherry (Thalasherry) in North Malabar. A very fabulous fake story has been woven by the film media around the ‘great’ king Pazhassiraja of ‘Kottayam’.

The word Kottayam or Cottayam is mentioned many times. However, they all pertain mostly to the ‘Kottayam’ that is in South Central Travancore. See this quote

The petty principalities of Tekkumkor (Changanachery) and Vadakkumkur (Kottayam and Ettumanur) having sided with the enemy in the Kayangulam war, the Dalawa next directed his forces against them............................. When the Brahmins fled, the resisting element in the war disappeared and the Dalawa had not to wait long to capture the Kottayam Rajah.

However the north Malabar Kottayam (Cottayam) has been mentioned here:

Potfuls of Roman coins and medals have been discovered at Vellore, Pollachi, Chavadipalayam, Vellalur, Coimbatore, Madura, Karur, Ootacamond, Cottayam in North Malabar, Kilabur near Tellichery, Kaliam putur, Avanasi, and Trevor-near Cannanore

There is one very definite mention of the ‘raja’ of north Malabar Kottayam (village). The mention is not very fabulous:

QUOTE: We have already referred to the fact that owing to the anarchy caused by Tippu’s followers many nobles and chiefs of Malabar took shelter in Travancore and were very hospitably treated there.........................................Among the Princes that took shelter in Travancore at the time were the Zamorin of Calicut, the Rajahs of Chirakkal, Kottayam, Kurumbranad, Vettattnad, Beypore, Tanniore, Palghat and the Chiefs of Koulaparay, Corengotte, Chowghat, Edattara and Mannur. The places mentioned here are mostly minute geographical areas.

The Malayalam film industry has made a film based on a fake history with the title Pazhassiraja. It is quite funny how history and historical events and individuals can so easily created.

1c17 #BALA RAMA VARMA

“The illustrious Rama Varma was succeeded by his nephew, Bala Rama Varma”

Bala Rama Varma was a youngster. He did face the problems associated with feudal languages, which assigns the lower indicant words to youngsters. The effects are there in his history.

It was to lead to quite destabilising events in the kingdom. It led to mismanagement, widespread corruption and then to the rise of Velu Tampi, who forced the king to make him the dewan. Tampi had to play a lot of manipulative games to manoeuvre himself in the position of power. He was brilliant in these activities of minor significance. He shifted from one side to another, whichever one he felt was better for him.

How he entered the mainstream attention is given in this quote:

This system of extortion continued for a fortnight; a large sum of money was actually realised, and numbers of innocent people were tortured. The tyranny became intolerable and the people found their saviour in Velu Tampi, afterwards the famous Dalawa.

Yet, Velu Tampi had only terror and barbarianism as a cure to the problems of the kingdom.

See these quotes:

1. the Namburi was banished and the other two had their ears cut off

2. Vein Tampi now coveted the Dalawa’s place. ............ But there were two able officers of the State, Chempakaraman Kumaran and Erayimman, brother and nephew of the late Kesava Das, whose claims could not be righteously overlooked. Velu Tampi and his accomplices formed a conspiracy to get rid of these two men. Kunjunilam Pillai made false entries in the State accounts and showed a sum of a few lacs of rupees as due to the treasury from the late Kesava Das. The two kinsmen were in a fix and appealed to their European (English) friends at Madras and Bombay asking for their advice and intercession. These letters were intercepted and their spirit misrepresented to the Maharajah as importing disaffection and other letters were forged to show treasonable correspondence of the two gentlemen with Europeans abroad. The King, then less than twenty and quite unequal his high responsibilities, ordered their immediate execution. The two officers were accordingly murdered in cold blood, and Velu Tampi’s claim stood uncontested.

3. Velu Tampi was a daring and clever though unscrupulous man. Rebellion was his forte. He was not in any sense a statesman, for he lacked prudence, probity, calmness and tact — qualities which earned for Rama lyen and Kesava Das immortal fame. He was cruel and vindictive in his actions. His utmost merit lay in the fact that he was a strong man and inspired dread. Within three years of the death of Kesava Das, the country was in a state of chaos; the central government became weak and corruption stalked the land. Velu Tampi’s severity, excessive and sometimes inhuman, completely extirpated corruption and crime from the country. His favourite modes of punishment were: imprisonment, confiscation of property, public flogging, cutting off the palm of the hand, the ears or the nose, impalement or crucifying people by driving down nails on their chests to trees, and such like, too abhorrent to record here. But it may be stated in palliation that the criminal law of the Hindus as laid down by their ancient lawgiver Manu was itself severe. The Indian Penal Code is also much severer than the code of punishment prevailing in England.

4. Strict honesty was thus barbarously enforced among public servants and order prevailed throughout the kingdom. Velu Tampi became an object of universal dread.

5. See this sample QUOTE on how cases were enquired upon: .........The local Mahomedans had committed the robbery on the innocent Nambudiri. Of this fact Velu Tampi satisfied himself. He ordered the whole of the Mahomedan population of Edawa to be brought before him, and when they as a matter of course denied the charge, he mercilessly ordered them one after another being nailed to the tree under which he held court. When two or three Mahomedans had been thus disposed of, the others produced the Nambudiri’s chellam with all the stolen goods in it intact.

Velu Tampi did display administrative capacities. Yet, see this quote:

The treasury was now empty. Zeal for the public service was waning; the revenues were not properly collected owing to personal bickering and retaliations at headquarters such as those which disfigured the relations between Velu Tampi and Kunjunilam Pillai.

Even though jingoist historian would attribute this financial problem to the subsidy that had to be given to the English East India Company as the expense for maintaining the protective military force in the kingdom, the fact remains that later when the kingdom was perfectly managed with English help, not only was the arrears paid off, but there was a great financial surplus.

See these QUOTES:

1. “The financial position of the Travancore State still continues to be very satisfactory and is most creditable to His Highness the Rajah and to his experienced and able Dewan Madava Row

2. “The financial results of the administration of Travancore for 1864-1865 are, on the whole, satisfactory, and the surplus of Rupees 190,770 by which the Revenue exceeds the expenditure appears to have been secured notwithstanding heavy reduction of taxation, under the enlightened and able administration of the Revenue Department by the Dewan Madava Row.

1c18 #GOURI LAKSHMI BAYI

After Bala Rama Varma, came the rule of GOURI LAKSHMI BAYI. In many ways it was quite a remarkable period of rule. Though quite young (barely twenty), she had the maturity to write thus:

“there was no person in Travancore that she wished to elevate to the office of Dewan and that her own wishes were that the Resident should superintend the affairs of the country as she had a degree of confidence in his justice, judgement and integrity which she could not place in the conduct of any other person”.

In the speech delivered by her when she was placed on the musnud, she addressed the British Resident as Ethreijum Bahumanapetta Sahabay. It points to the fact that the terrible local vernacular inferiorities had infected the royal family also. For, even a minor Indian kid who lives in England would address the Colonel as Colonel Munro. That she is not able to do so, speaks volumes of the training that the royal family members were forced to endure, by their own family members. Yet, she understands her predicament as speaks thus:

“I cannot do better than to place myself under the guidance and support of the Honourable East India Company, whose bosom had been an asylum for the protection of an infant like Travancore, since the time Sri Padmanabhaswamy had effected an alliance with such a respectable Company of the European nation. To you, Colonel, I entrust everything connected with my country, and from this day I look upon you as my own elder brother and so I need say no more.”

In every sense, she was also following the footstep of her great ancestor king Marthanda Varma in this policy. Isn’t there some quirkiness of fate that in a few decades after her rule, there would be another queen bearing the same name LAKSHMI BAYI of a small-time kingdom in the northern areas of the Indian peninsula (Jhansi) who acquired the reputation of a ‘freedom fighter’ against the East India Company. In Travancore, Laxshmi Bayi is a ruler who supports English domination, while the latter is a person who went against the English and ultimately got lost in the melee of mutual bickering of the mutinous sepoys and their mutually antagonistic leaders.

When Col Munro took up the Diwanship for a brief period, this was what he saw:

“No description can produce an adequate impression of the tyranny, corruption and abuses of the system, full of activity and energy in everything mischievous, oppressive and infamous, but slow and dilatory to effect any purpose of humanity, mercy and justice. This body of public officers, united with each other on fixed principles of combination and mutual support, resented a complaint against one of their number, as an attack upon the whole. Their pay was very small, and never issued from the treasury, but supplied from several authorised exactions made by themselves.

“They offered, on receiving their appointment, large nuzzers to the Rajah, and had afterwards to make presents, on days of public solemnity, that exceeded the half of their pay. They realised, in the course of two or three years, large sums of money .......................... “

Most of the things mentioned about the officialdom by Col Munro are true of current day Indian bureaucrats also.

During the time of Kesava Das as the Diwan, this rule had to be promulgated with regard to the powers of the official:

and on no account shall a female be detained for a night.

1c19 #THE TRAGIC REIGN of SWATI TIRUNAL

The tragedy that befell the life of the next king Rama Varma otherwise known as Swati Tirunal is there in these lines written by Col. Welsh who made it a point to observe the educational development of the young prince, who was being tutored by a Maharashtra Brahim:

He then took up a book of mathematics, and selecting the 47th proposition of Euclid, sketched the figure on a country slate but what astonished me most, was his telling us in English, that Geometry was derived from the Sanscrit, which was Ja** ***ter to measure the earth, and that many of our mathematical terms, were also derived from the same source, such as hexagon, heptagon, octagon, decagon, duo-decagon, &c.

The Englishmen did not understand the powerful hold that ‘teachers’ have on their wards, through the clasping hold of lower indicant words. The use of such words as Nee (Inhi), Avan (oan), Aval (Oal), Avante (onte), Avalude (olde) etc. can fix powerful strings on the physic, psyche and social positioning of the student. The Maharastra Brahmin, Subba Row, the tutor was later posted as the Diwan of the kingdom, when Swati Tirunal became the king. More or less, creating a lifelong encumbrance on him in the form of a superior and capable-of-commanding, subordinate.

As to the claim that all modern knowledge flowed from ‘India’, it is a dumb one. It is true that there were great technical skills, technology etc. at some or various periods in the long past history of the Indian peninsula, extending backwards to tens of thousands of years. The same is the fact with regard to the geographical areas now identified as Ancient Egypt, Ancient South America, Ancient China etc. Even Ancient Continental Europe may have had its share of these things. As to England, it was a very small island outside the periphery of Continent Europe. It was a nation that stood apart from everything, including the fact that rarely has it tried to conquer other nations in Europe using military campaigns.

However, the fact is that there is no direct line from these ancient technical knowledge to what came here from the English education that was propagated by the English rulers. When the Indian peninsula was made into a single nation by the English, naturally there would be feeling that what was being taught by the English can be traced to ancient texts found here and there in some houses, and in the technical skills of certain class of people.

For example, see the case of the Vedas. The ancient Vedic period area is generally connected to the geographical areas occupied by current day Pakistan. Moreover to give a direct bloodline link to those people would be quite foolish. For each person currently living in India would be connected to billions of people living on this earth at that time. But then there were presumably no billions of people on this earth then.

It is like this. One individual has two parents. Each of them has two parents each. That means four links to the present individual.

If we go back like this, it would be found that some 21 generations back (i.e. 350 years back), this individual would be linked to 20 lakh persons living 350 years back. Now, if we go back to 7000 years, then it would mean that this present day individual is linked to almost all human beings living on this earth. For even in minute Kerala, people from Middle East, China, Far east, Europe and Africa have come and lived. A single link that connects to Africa or Europe can link the present day Kerala individual to almost all persons of Africa or Europe some 7000 years back.

Beyond all this, no one knows who wrote the Vedas. It is the same case with the Holy Quran and the Hebrew Bible. What was the machinery used for their creation is not known. It is possible that these texts do contain powerful codes, as one would identify software codes in present day times. How many of the present Indians know the secrets of the Vedas? Of the codes therein? Of the machinery and men who created it?

There is one character in a book by the famous Malayalam writer Vaikom Muhammed Basheer, by name ETTUKALI MAMMOONCHU. The present day Indian feature of claiming everything mentioned in the modern discoveries as their own is reminiscent of this character.

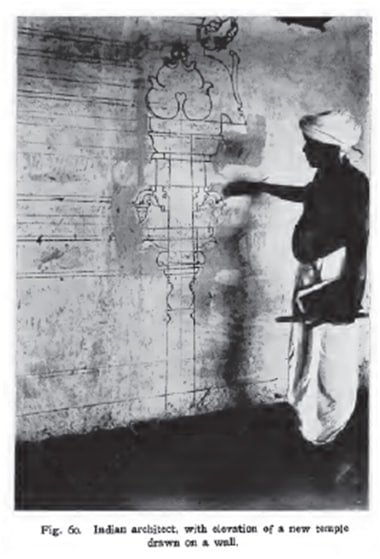

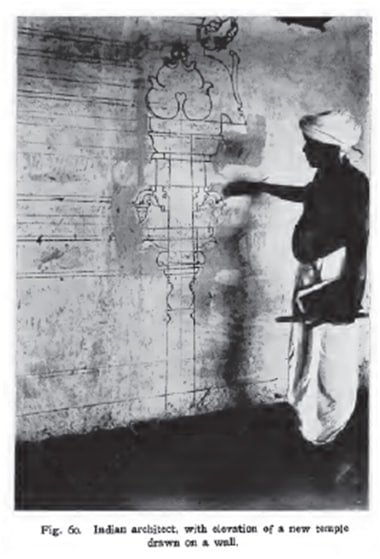

Speaking more about the knowledge that abounds in this geographical area, just look at the ordinary carpenters of the place. I have seen, in my childhood days, absolutely fantastic Master Carpenters who could envisage a huge building architecture without the means of any sophisticated gadgetry. In British-Indian writings I have seen the word ‘Indian-Architect’ used to describe them. They had knowledge, skills and technical information that could vive with the architects of England. Yet, no local Brahmin man here would send his children to study under these Carpenters. For, it would be quite a foolhardy thing to do. For, it would arrive them at the Nee, Avan, Avante and eda levels under technical persons who existed at the lower levels in society.

However, if any of these carpenters had been taken to England after learning English, they would have bloomed into geniuses like Ramanujams. They would have come out with fantastic books and treatises on Architecture, woodcraft, timber quality and much else, including a master book on Vastushastra. Yet, they wouldn’t be able to create a fabulous nation like England. Herein lies another truth. That, technical skills do not create a great nation. Great nations are created by quality citizens. For citizens to be quality, they require a language like English, which doesn’t depreciate the value of individual, and discriminate between them.

Now coming back to Swati Tirunal, he couldn’t get along well with the English Resident. The basic fault can be traced back to the low-quality tutoring he got from his Maharatta Brahmin Tutor. Why the Royal family did not opt for an English tutor is the moot point. For, such a training would have elevated the young prince beyond the messy holds of the messy feudal vernaculars of the locality. There is indeed an answer to this Why. It is that his own various relatives wouldn’t want him to go beyond their own clasping holds of feudal word strings.

Swati Tirunal’s brother, when he became the king had a very nice relationship with the same English Resident, with whom his elder brother couldn’t get along well.

1c20 #TRADE AND CRUDE OFFICIALS

There are certain other insights that this book brings out. One is that in British-ruled-Malabar trade was free. Anyone could sell to whomsoever they wished. However, in Travancore, almost all trade in commodities was monopolised by the government. This involved the corrupt officials. Just like the current-day official dacoits, the Sales Tax officials. [In between, it may be mentioned that during the British rule time, there was no Sales Tax, until the Indian ministry in Madras Presidency pushed for one, when the English rule was on the verge of ending]

Now speaking about officials, it is not easy to convey the tragedy of the people of being under officials in the Indian peninsular region. The vernaculars are feudal, degrading and suppressive to the people. The officials can and would use such words as Nee, Avan, Aval, Avattakal, etc. to and about the people. The terror and tragedy this means for the ordinary man cannot be expressed in English. For, there is no way to convey the Satanic emotions that is conveyed through these words. When speaking about freedom, one has to take into account, the language of the people. There is no meaning in the word ‘freedom’ if the language is feudal.

The policeman in free India addressing an ordinary man in India as Nee and referring to him as Avan, Avattakkal and eda, does not convey any freedom. Even a slave under a racist Englishman would be having a thousand times more freedom. However, the other side is also there. The policeman cannot be polite to the ordinary man. For, in the Indian schools under low-quality teachers, he has been trained to ‘respect’ rudeness of the superiors. For example, in government schools in Kerala, the students are addressed as Nee, and referred to as Avan and Avattakal. Words such as Eda, Enthaada etc. are also used. The students have to get up to show ‘respect’ to the teacher. He cannot sit with a straight back and talk in a manner conveying self-dignity. He has to cringe and bent, and bow and clasp his hands in the pose of subservience (Namaskaram). If he is inclined to stand straight and talk to the teachers with a pose of dignity, he is seen as impertinent.