11. The sweetness of wild honey and the poison of the wild wasp

11. The sweetness of wild honey and the poison of the wild wasp

Written by VED from VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

Previous page - Next page

1. When translating English words into feudal languages, it feels that a dagger or whip is being embedded within

2. Observations on Malayalam and Tami

3. Deficiency in classifying people as Dravidians and Aryans

4. Some observations on language scripts

5. The depth, expanse, and origin of Indian nationalism and Hindu tradition in post-1947 India

6. On the concept of a Fundamental Script

7. On the integration into a grand Vedic Indian culture

8. A linguistic tradition with the sweetness of wild honey and the venom of a forest wasp

9. On the three groups hanging and clinging to the top of society

10. On the gradual changes in social perspectives and outlooks

11. Feudal languages creating invisible ornamental pattern designs in the mind

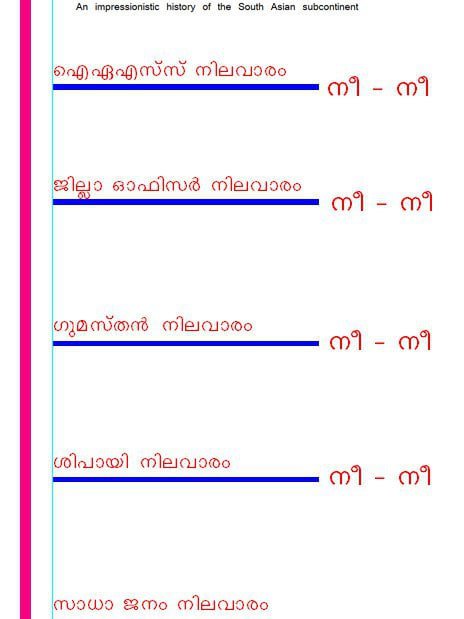

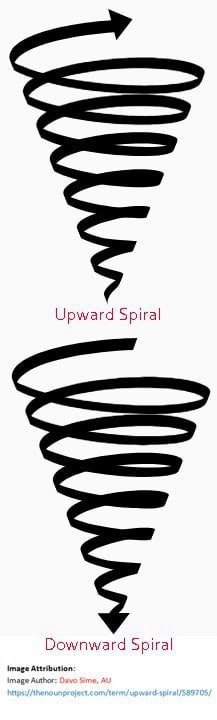

12. The dark shadow of 'nee - nee' equality in social hierarchy

13. The social structure like a deep well atop a dry mountain and the motorcycle stunt

14. Into the inner locations of marriage prospecting

15. Feudal language marriages and English language marriages

16. The feudal language mechanism behind honour killing

17. Relationships and word codes that drastically pull personality upward and downward

18. About the invisible platform of software

19. About binary digits

20. Design possibilities beyond the laws of the physical world

21. Treatment method involving touching and manipulating fragmented codes in the ultra-subtle software system

22. On the oscillation of feudal language word codes in the values of ultra-subtle software codes

23. Nothing in human hands today is advanced enough to compare with ultra-subtle software

24. Integrating codes related to another person into the codes of an individual’s body and mind

25. On matters capable of causing ebbs and flows in energy levels

26. The presence of information and explanations at various levels, delving deeper in layers & stages behind physical events

27. The shift towards bestiality from subtle to profound levels in code view

28. The language-social environment that perceives elevated personality as having people suppressed beneath

29. About Namboodiris

30.To be freed from the rigid walls of respect, the cruel feudal linguistic atmosphere in the land must be erased

31. It was the English company that saved the Nambudiris from the shackles of untouchability in Malabar

32. When vulgarity radiates from the hierarchical levels of social inequalities

33. A significant mental shift among Nair women

34. Do not touch without clearly understanding what is on a person’s body

35. An erotic event that shakes the foundation and structure of society

36. An experience like an earthquake or falling into a pit for Namboodiri women

37. The English administration itself liberated the Namboodiris in Malabar

38. The likely unbearable life of Namboodiri women

39. The dance of women whose golden words enhance their physical splendour

40. A situation where one’s own servant truly stands as a threat in life

41. How the presence of the lower classes speaking feudal languages influences and affects the demeanour of those above

42. When the soul is struck by words that pour in filth

43. A state of being dried up, emaciated, and blackened

44. A demonic nature that cannot be detected in English in any way

45. The deep abyss is indeed a terrifying depth

46. The presence and power of divinity in verbal codes

47. The lowest ranks among Namboodiris

48. Those permitted to perform the sixteen rituals known as Shodakriyakal

49. Pumsavana samskaram and Seemanthonnayanam

50.A supernatural system to block negative influences from invading the new mind

Previous page - Next page

Vol 1 to Vol 3 have been translated into English by me directly.

From Vol 4 onward, the translation has been done by a translation software. So there can be slight errors in the text.

It was slightly difficult to make the translation software to understand that in Indian languages, there are hierarchy of words everywhere.

From Vol 4 onward, the translation has been done by a translation software. So there can be slight errors in the text.

It was slightly difficult to make the translation software to understand that in Indian languages, there are hierarchy of words everywhere.

1. When translating English words into feudal languages, it feels that a dagger or whip is being embedded within

2. Observations on Malayalam and Tami

3. Deficiency in classifying people as Dravidians and Aryans

4. Some observations on language scripts

5. The depth, expanse, and origin of Indian nationalism and Hindu tradition in post-1947 India

6. On the concept of a Fundamental Script

7. On the integration into a grand Vedic Indian culture

8. A linguistic tradition with the sweetness of wild honey and the venom of a forest wasp

9. On the three groups hanging and clinging to the top of society

10. On the gradual changes in social perspectives and outlooks

11. Feudal languages creating invisible ornamental pattern designs in the mind

12. The dark shadow of 'nee - nee' equality in social hierarchy

13. The social structure like a deep well atop a dry mountain and the motorcycle stunt

14. Into the inner locations of marriage prospecting

15. Feudal language marriages and English language marriages

16. The feudal language mechanism behind honour killing

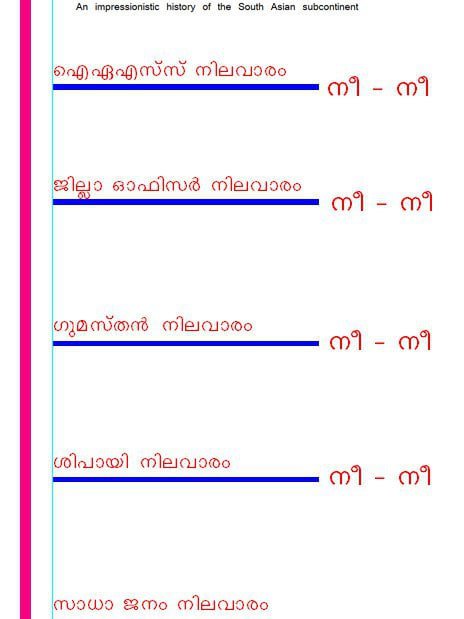

17. Relationships and word codes that drastically pull personality upward and downward

18. About the invisible platform of software

19. About binary digits

20. Design possibilities beyond the laws of the physical world

21. Treatment method involving touching and manipulating fragmented codes in the ultra-subtle software system

22. On the oscillation of feudal language word codes in the values of ultra-subtle software codes

23. Nothing in human hands today is advanced enough to compare with ultra-subtle software

24. Integrating codes related to another person into the codes of an individual’s body and mind

25. On matters capable of causing ebbs and flows in energy levels

26. The presence of information and explanations at various levels, delving deeper in layers & stages behind physical events

27. The shift towards bestiality from subtle to profound levels in code view

28. The language-social environment that perceives elevated personality as having people suppressed beneath

29. About Namboodiris

30.To be freed from the rigid walls of respect, the cruel feudal linguistic atmosphere in the land must be erased

31. It was the English company that saved the Nambudiris from the shackles of untouchability in Malabar

32. When vulgarity radiates from the hierarchical levels of social inequalities

33. A significant mental shift among Nair women

34. Do not touch without clearly understanding what is on a person’s body

35. An erotic event that shakes the foundation and structure of society

36. An experience like an earthquake or falling into a pit for Namboodiri women

37. The English administration itself liberated the Namboodiris in Malabar

38. The likely unbearable life of Namboodiri women

39. The dance of women whose golden words enhance their physical splendour

40. A situation where one’s own servant truly stands as a threat in life

41. How the presence of the lower classes speaking feudal languages influences and affects the demeanour of those above

42. When the soul is struck by words that pour in filth

43. A state of being dried up, emaciated, and blackened

44. A demonic nature that cannot be detected in English in any way

45. The deep abyss is indeed a terrifying depth

46. The presence and power of divinity in verbal codes

47. The lowest ranks among Namboodiris

48. Those permitted to perform the sixteen rituals known as Shodakriyakal

49. Pumsavana samskaram and Seemanthonnayanam

50.A supernatural system to block negative influences from invading the new mind

Last edited by VED on Sat Aug 09, 2025 12:41 pm, edited 11 times in total.

1. When translating English words into feudal languages, it feels as though a dagger or a whip is being embedded within

In the Malabari language, the various indicant word codes for 'She' are as follows: 'Olu', 'Oru'.

Another term, 'Mooppathi', exists but is not being discussed here for now.

The indicant word codes for 'He', such as 'Onu' and 'Oru', are quite similar to those for 'She'.

It seems that the terms 'Oru' and 'Oru' are sometimes used interchangeably. In other words, 'Oru' may be associated with 'He', and 'Oru' with 'She', based on usage.

Additionally, it appears that the words 'Oru' and 'Oru' are also used for the English word 'They'.

Upon close examination, it seems that these words are not exactly equivalent in Malayalam. However, there is a sense of some similarity.

In Malayalam, the various indicant word codes for 'She' are as follows: 'Aval', 'Pulli', 'Pullikkari', 'Ayaal', 'Avaru', 'Sir' / 'Maadam', and so forth.

We can assume, if needed, that 'Aval' in Malayalam corresponds to 'Olu' in Malabari. Similarly, 'Avaru' in Malayalam can be considered equivalent to 'Oru' in Malabari. However, there is no direct equivalent for 'Ayaal' in Malabari.

It was mentioned earlier that the expression 'Aa Aal' exists in Malabari, but it is not the same as 'Ayaal' in Malayalam. Likewise, the term 'Maadam' might be a recent addition to Malayalam usage. Decades ago, women in high or low official positions were addressed and referred to as 'Sir' by common citizens to express subservience.

Moreover, terms like 'Pulli', 'Pullikkari', and 'Pullikkaran' seem to have entered Malayalam from the conversational style of some Christian community. The exact truth of this is unclear.

The Malabari and Malayalam forms of 'She' create vastly different attitudes in individuals within the social atmosphere. This was mentioned at the beginning of this writing (Vol 1 – Chapter 8 - Malabari and Malayalam).

In Malabari, a woman referred to as 'Olu' might express extreme subservience or, conversely, be seen as defiant and mischievous. At the same time, if this same woman shifts from 'Olu' to 'Oru', she may be perceived as overly bold, possessing a strong personality, expecting subservience from others, socially engaging, and having the mental fortitude for such interactions.

In contrast, in Malayalam, even if a woman evolves from 'Aval', a sudden transformation is not necessarily expected. This is because, rather than being placed directly at the highest level, there are various indicant word codes for 'She' that allow for gradual elevation in status.

Although differences between Malabari and Malayalam have been noted, there is also a close connection between the two.

Is not the Malayalam 'Nee' the same as the Malabari 'Inhi'? Could it be that the degradation and loss of quality in Malayalam words, when handled by people lacking education and cultural values over time, resulted in the state of Malabari words? One might think so.

The issue with the above points is that Malabari has been a language native to Malabar from ancient times. In contrast, Malayalam is a language that emerged and developed more recently in Travancore, with Tamil heritage. Furthermore, the lower-class Christians and Ezhavas, who brought Malayalam into Malabar, were traditionally from the lower strata of society. Yet, it is their language form that claims superior quality.

However, if one rejects the claim that Malabari is a degraded form of modern Malayalam, there is no issue.

One could argue that 'Inhi' is not a degraded form of 'Nee'.

Nevertheless, something common observed among the words 'Nee', 'Tu', and 'Inhi' is worth noting here.

Consider the Malabari 'Inhi', Hindi 'Tu', Tamil 'Nee', Malayalam 'Nee', German 'Du', and Irish 'Tú'. These words are understood to be the lowest-level indicant word codes for 'You' in these respective languages.

There is a sense that these word forms, used to address those placed at the lowest rung, all possess a sharp, piercing sound.

It seems that in feudal languages, the sounds of such words are coded with an invisible mechanism designed to wound, demean, or subtly hook and hold a person, as if caught on a fishing line.

At the same time, the indicant word codes used for relatively higher-status individuals in these languages seem to lack this sharp, piercing quality.

In Malabari: 'Ningal' / 'Ingal'

In Hindi: 'Tum', 'Aap'

In Malayalam: 'Ningal', 'Thangal'

In Tamil: 'Neengal', 'Ungal'

And so forth. (I believe the Tamil forms listed here are correct, though I am not certain).

The English word 'You' naturally lacks the sharpness to pierce or weaken a person’s identity or the varied intonations that comfort, strengthen, or affirm it.

However, if 'You' is mentally translated as 'Nee', it may feel as though it gains a certain sharpness. If not translated in this way, that sharpness is not perceived.

In reality, translating English words and sentences into feudal languages can feel like embedding a dagger or a whip within them. Sometimes, it might feel like they are laced with honey and sweetness instead.

Alternatively, it is also possible to experience them as wrapped in rays of pure golden honey. It all depends on which level of indicant word code in the feudal language the English words are translated into.

The issue raised here is the danger of teaching English in Indian formal education as a translated form of local feudal languages. This is a critical matter in the current discussion on the ornamental design of languages. I believe a few points on this can be addressed after one or two more writings.

Today’s writing concludes here.

2. Observations on Malayalam and Tami

C.A. Innes, I.C.S., in his work Malabar and Anjengo, makes the following observation:

Malayalam is a Dravidian language closely akin to Tamil; but it is still a matter of dispute whether it should be regarded as an “old and much altered offshoot” of Tamil as Dr. Caldwell considered it, or as a sister language “both being dialects of the same member of the Dravidian family,” as Dr. Gundert suggests in his dictionary.

Dr. Caldwell, mentioned above, was a South Asian language scholar during the English administration.

I must first state the limitations of what I am about to write. I am not a language scholar. Everything written here is based on casual observations gathered from daily life over time. Many scholars who have studied these matters in depth may have already noted these points. There is no intention here to challenge their knowledge or findings. However, I am unaware of the specifics of their discoveries.

It is often said that Tamil and Malayalam are closely related languages. The extent of this truth is unclear to me.

Words like 'Nee', 'Eda', 'Edi', 'Avan', 'Aval', and 'Avaru' are widely used in both Tamil and Malayalam. Furthermore, I understand that the word 'pennu' is of Tamil origin. In Malayalam, 'pennu' is, to some extent, considered a pejorative term. There are points worth discussing regarding this word, but I will not delve into that now.

I understand that words like 'Ningal' and 'Thangal' in Malayalam have equivalent expressions in Tamil, with slight phonetic differences. Similarly, words like 'avide' (there) and 'ivide' (here) seem to have near-equivalent sounds in Tamil.

However, I believe a Malayalam speaker with no knowledge of Tamil would not easily understand Tamil. Likewise, a Tamil speaker familiar only with Tamil would likely struggle to comprehend the Sanskrit-derived words in Malayalam.

There are also words in Malayalam and Tamil that have different meanings despite being the same. For example, I understand that the word 'panni' exists in Tamil. In Malayalam, it is an offensive term, while in Tamil, it appears to be a common, non-offensive word used in daily conversation.

Similarly, words like 'samsaram', 'mudichu', and 'kettu' are said to have different meanings in Tamil and Malayalam.

Consider this Tamil phrase:

Vazhkayella eppadi irukku?

(வாழ்க்கையெல்லா எப்படி இருக்கு?)

(The Tamil words written above may not be entirely accurate.)

Without any knowledge of Tamil, one would not understand what this means.

Take the old Tamil film song from Annakili. Some words in this song seem to have a connection with Malayalam words. However, for someone with no knowledge of Tamil, it may take time to grasp the song’s precise meaning.

The above are merely some thoughts that came to mind and have been jotted down here.

Returning to the main discussion, I have noticed one or two words in Malayalam and Malabari that share the same sound but differ in meaning.

However, it does not seem that pure Malabari has been influenced by Tamil. If any influence is observed, it may have come from Malayalam or from interactions with the Tamil people in ancient times.

As noted earlier, it has been recorded that Malabari contains very few Sanskrit words.

In the software coding of languages, one might observe commonalities in their phonetic structures. As mentioned earlier, words meant to wound or suppress may have a sharp, piercing sound.

Consider these English words:

There: avide

Here: ivide

If one points to a distance and says “Here” or points nearby and says “There,” would it not take some time for someone unfamiliar with the language to understand the intended meaning? I am not certain, but it seems that the sounds of words indicating proximity or distance may contain some directional coding.

Doesn’t the word There have a sound that suggests something distant?

Doesn’t the word Here have a sound that implies something nearby?

This phenomenon is noticeable in South Asian languages:

Malayalam: ivide (here), avide (there)

Tamil: inge (இங்கே, here), angu (அங்கு, there)

Hindi: yahaan (यहाँ, here), wahaan (वहाँ, there)

Similarly:

Ivan (this man), Avan (that man)

Ival (this woman), Aval (that woman)

Proximity and distance.

In this regard, Malabari differs from modern Malayalam in one or two specific words.

Ivan - Avan: In Malabari, there is only one word, Onu. The word Inu does not exist.

Ival - Aval: In Malabari, there is only one word, Olu. The word Ilu does not exist.

The reason for this is unclear.

This may be a significant aspect of the software coding of languages. I have nothing further to say on this matter. However, it should be noted that this represents a difference in the ornamental design of languages.

Yet, the claim that Malayalis and Tamils are both Dravidians under a common ethnic identity raises questions about its accuracy.

During the English administration in South Asia, it was a common notion in the writings of English officials that northerners were Kshatriyas and southerners were Dravidians. Scholars, who gain knowledge by reading and studying others’ works, seem to have adopted this view as well.

The accuracy of this information is uncertain. However, many doubts and pieces of information arise in the mind.

I will address these in the next writing.

My writing concludes here for today.

3. Deficiency in classifying people as Dravidians and Aryans

There is a prevailing notion, perception, or scholarly opinion that the southern parts of South Asia were traditionally inhabited by Dravidians, while the northern parts were home to Aryans. There is also a widespread belief in some quarters that Aryans possess a commanding personality, while Dravidians are akin to a primitive, tribal-like group.

I have no knowledge of anthropological studies or detailed readings related to this topic. Therefore, what I am about to write is based solely on trivial observations. These points should be given only as much weight as they deserve.

I understand that Tamil Nadu is home to numerous distinct castes and, consequently, diverse groups of people. Among them, a significant number are observed to have very dark skin. One reason for this might be the intense heat and harsh sunlight in Tamil Nadu during the day.

However, another possible reason could be the rigid hierarchical nature of the Tamil language. Tamil has indicant word codes capable of harshly suppressing those at the lower rungs. Moreover, the language’s structure compels those at the bottom to express subservience, loyalty, and affection in their speech, posture, and behavior.

It seems that this could cast a shadow of darkness on both the body and the mind. Whether this can be definitively proven is uncertain.

I have also seen very fair-skinned Brahmins in Tamil Nadu, some with a slight tinge of darker skin. I do not recall noticing the effects of harsh sunlight or the darkness spread by the language codes of lower-status individuals in them. I am unsure of the reality today.

If a few people show great subservience and respect in the presence of someone, feudal languages can bring immense clarity and energy to the mind and a glow to the body. This could be demonstrated by the converse: if lower-status individuals speak demeaningly in feudal language codes without showing subservience, it may lead to darkness in the mind, a drain of energy, physical fatigue, and intense resentment in demeanor.

I have not observed that Brahmins in Tamil Nadu resemble those from northern South Asia in appearance.

Telugus, Tamils, Sinhalese, Kannadigas, Malayalis, Tulus, some Marathis, Irulas, Kurumbas, Paniyas, and others are classified as Dravidians, according to various nonsensical entries on Indian Wikipedia pages.

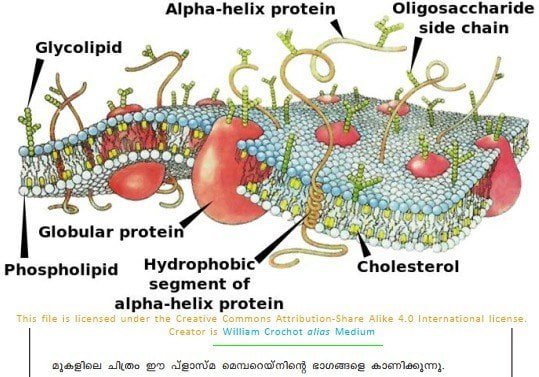

It seems that images labeled as “Dravidians” in various sources often depict people traditionally oppressed by regional language codes. See the image provided below.

There may be some similarity between Telugus and Kannadigas. The Sinhalese could perhaps be included in this group. However, it does not seem that Tamils can be grouped with them. Among these four groups, one might find diverse individuals. If they speak the same language over generations and live at similar social levels, similarities in facial features, body structure, and, to some extent, skin tone may emerge. The reality is that feudal language codes have the qualities and abilities of a chisel, a whip, a hammer, and a paintbrush.

Take the people of Malabar, for instance. Consider the Cherumars. C.A. Innes, I.C.S., in Malabar and Anjengo, notes that they are Pulayas. This is a designation given by the upper classes. When the upper classes recorded that Thiyyas are Ezhavas, many Thiyya families argued, “We are not Ezhavas,” and they were able to assert this. However, the Cherumars, suppressed to the lowest rung by social and language codes, likely had no opportunity to express an opinion on how they were documented.

Kurumbas, Kurichiyas, Parayas, Pariyars, Malayas, Marumakkathayam Thiyyas, Makkathayam Thiyyas, Nairs, Ambalavasis, and Namboodiris do not seem to be the same people. Even within these groups, some share the same caste name but have no connection. Some had languages incomprehensible to others.

Additionally, Malabar has traditionally been home to Mappilas. Among them, certain families maintain exclusive marital ties with those of clear Arabian lineage. I understand that most of those commonly known as Malabari Mappilas today are a mix of Cherumar, Makkathayam Thiyya, Nair, Ambalavasi, and Brahmin blood with specific Arabian lineages.

Beyond these, Malabar today includes Ezhavas, lower-class Christians, and Syrian Christians from Travancore.

Among these three groups, it seems unlikely that Syrian Christians have any anthropological connection with Tamils. Ezhavas may have had some connections in ancient times.

When examining language scripts, Telugu, Kannada, and Sinhala appear to use rounded, potato-like scripts. Tamil scripts, however, are entirely distinct.

I am not addressing the Vattezhuthu script here. Malayalam scripts differ from both of the above-mentioned script groups.

There is a lingering doubt in my mind whether these scripts were brought from the Malabari language to Travancore. By the time they arrived, they may have undergone slight modifications to accommodate the large influx of Tamil and Sanskrit words used to create modern Malayalam.

Searching “Dravidian” on the internet gives the general impression that Dravidians are an unrefined group. There is also a sense that Aryans are considered highly civilized. There is no dispute that Brahmins in Malabar claim to be Aryans. Similarly, Nairs make the same claim. Even if they are traditionally Shudras, they consider themselves part of the Aryan lineage. However, it seems that many Nairs today have very little Shudra blood, likely carrying predominantly Namboodiri lineage.

If any of the people mentioned above were to live in England, I believe that within one or two generations, their descendants would undergo significant anthropological changes. The reality is that language codes can profoundly influence human physical structure.

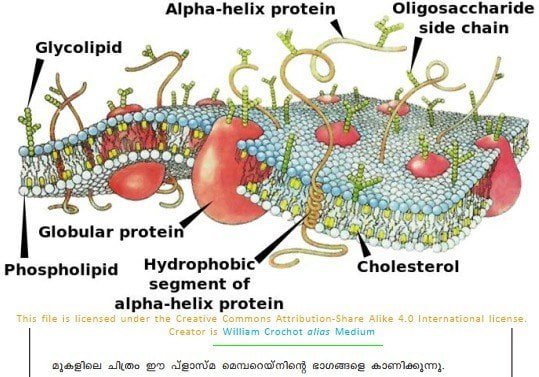

The image provided in the previous page is of my first daughter in her early childhood, likely around two years old. I recall a comment made by an IAS officer I knew while I was in Delhi, when my first daughter was about four years old:

“You have Malayali looks. However, your daughter doesn’t have one bit of Malayali looks.”

I claim that this change in anthropological appearance was brought about solely through the linguistic environment. This was not merely due to teaching her English or avoiding other languages. Rather, it was made possible by carefully shielding her from the presence or influence of feudal languages. Admittedly, this was not fully achieved. I believe more on this can be discussed later (see Shrouded Satanism in Feudal Languages).

In individuals with this appearance genetically, it might be possible without any linguistic interventions. However, in my case, there is no such genetic heritage in my family.

A clear decline in this appearance occurred when my first daughter was forcibly enrolled in a local English-medium school. I cannot elaborate on this now. However, although my experiment faltered, it is worth noting that I was able to recognize the changes brought about by the local linguistic environment. Feudal languages create an environment that almost entirely subverts the mental, social, educational, and other aspects of the English-language environment.

I believe that the so-called “crude” Dravidian appearance can be altered through language codes alone. To be precise, any anthropological appearance can be transformed through the linguistic environment. I cannot agree with the foolish belief of Indian formal scholars that Aryans are superior.

At the same time, it seems that those living in the southern parts of South Asia may not all be collectively known as Dravidians. My experience suggests that the linguistic environment can even turn straight hair into curly hair.

Search for images of Dravidians on the internet. It may be noted that the descendants of those who traditionally lived in the southern parts of South Asia are today’s southern Indian population.

4. Some observations on language scripts

I have attempted a simple inquiry into where the Malabari language originated, or which group of people—whether migrants to Malabar or those subjugated there—might have spoken it. However, it seems that no substantial information has been found in this regard.

Before concluding this topic, let me mention a few more points.

Although there appear to be significant differences between the scripts of Tamil, Sanskrit (which likely came from outside South Asia), Malayalam, Telugu, Kannada, and other languages, there are also notable similarities among them. The vowels a, ā, i, ī, and consonants ka, kha, ga, gha, ṅa, etc., in Devanagari (Sanskrit script) and Tamil are not exactly identical but share some resemblance. Here, I am specifically focusing on Tamil and Sanskrit.

Malayalam likely drew influences from both.

When discussing scripts, two distinct aspects come to mind.

The first is the process of transforming spoken language into scripts. Without scripts, human speech would merely be sounds. Creating scripts from spoken sounds in a systematic and organized manner must have been a monumental task initially. Once created, making significant changes or refinements to these scripts likely required comparatively less effort.

Today, because scripts exist and people learn them, this process is rarely considered. Understanding spoken sounds, categorizing them into distinct words, breaking those sounds into components, and then representing them as scripts is a significant intellectual endeavor. This might be a task that computers can perform with ease. Keep this in mind.

George W. Stow, F.G.S., F.R.G.S., in The Native Races of South Africa, mentions that Dutch traders in African regions encountered people whose language was so difficult to pronounce that it seemed almost impossible.

Quote: “…but a sobriquet given to them by the early Dutch traders from the almost unpronounceable character of their language…”

The same book notes that many African groups considered the Bushmen, a tribal group in African forests, as mere animals, akin to wild game.

Quote 2: “…evidently classing the Bushmen and the game in the same category as wild animals.”

An English observer named Mr. Chapman is also cited as saying that learning the Bushmen’s language could allow humans to understand many unknown sensations of animals and nature.

Even today, there is no clear information about the sounds of animal languages. There are several points worth discussing on this topic, but that can be addressed later.

The point here is that the sounds of scripts in Sanskrit and Tamil show several similarities in how they were created. Vowels like a, ā, i, ī and consonants like ka, kha, ga, gha, ṅa exist in both, though not in the exact same order or form. Still, there seems to be a similarity in the sounds of their scripts. However, Tamil appears to have a distinct variation in the sound of its script endings.

The second aspect is the visual form of scripts.

It is unclear whether there is any connection between the visual forms of Tamil and Sanskrit scripts.

Consider this: In Sanskrit, the letter a is written as अ, while in Tamil, it is அ. In Sanskrit, ka is written as क, and in Tamil, it is க.

Most Malayalam scripts seem quite different from both.

It is unclear what to make of this. However, categorizing spoken sounds into scripts is one thing, while giving those scripts a visual form in writing is an entirely different matter.

Of these two aspects, it seems that similar intellectual processes occurred in Tamil and Sanskrit for the first. However, it is unclear whether different intellects were at work when creating the visual structure of these scripts.

The sounds of Malayalam scripts were likely derived from Sanskrit and Tamil. However, their visual form does not seem to come from either. This is merely a hunch, as I have no in-depth study or knowledge on this matter.

Let me briefly touch on English scripts here, without delving into their connection with continental European languages.

Consider the word for “mother” in South Asian languages: amma. This is similarly structured in Sanskrit, Tamil, and other South Asian languages. In English, it is written as Amma. Structuring human speech sounds in this way involves a significantly different intellectual process. It must be clearly stated that the creation of these two types of scripts (South Asian and English) likely involved entirely different intellectual capacities. I won’t delve deeper into this now, but the point is that English may be fundamentally different from South Asian languages in almost every way.

When I was studying in Trivandrum, an acquaintance once explained the influence of English scripts on Malayalam words. For instance, the word Mappila was pronounced under this influence as M A ppa ppa ila. In Travancore, Mappila refers to Christians.

Similarly, the word Makri would be pronounced as M A kri kri y.

This is written humorously from memory and should not be taken seriously.

It is understood that linguistic scholars have noted that English scripts have uppercase and lowercase distinctions, which South Asian languages lack. Additionally, English scripts involve compound letters and, relatedly, cursive writing (handwriting improvement practice). Today, cursive writing may have spread to South Asian and other languages.

The form of Malabar’s scripts may belong to a group that migrated, was subjugated, or traditionally lived there. However, it seems that the modern Malayalam scripts were created with deliberate attention to Sanskrit and Tamil.

Travancoreans today have little knowledge of Malabar’s traditional language, Malayalam. The same applies to Malabar’s younger generation. Often, mimicking a regional dialect from Malabar’s interior and claiming it as Malabar’s language leads to misunderstandings. Malabar’s Malayalam is not merely an accent but a language with words not traditionally found in Malayalam.

Words like cherayikk, othiyarkam, meethal, olumba, pathakknu, aye, oriyane, keenchu, ethakked, alamp, vellam, kothamalli, nilakkadala, adikk (sweep), nenthrappazham, idangar, kaikkott, thoombapani, thirinju, mel, makkar, suyipp, aand, kund, madamp, nireechu, and many others in this language—if found in other languages—could make it interesting to explore whether any group in Malabar’s traditional population has connections with those language speakers. Some Malabari words may clearly have connections with Arabic, but that is a separate matter.

Similarly, checking whether any Malayalam scripts appear in those languages would be equally intriguing.

It would be worth exploring whether the origin of Marumakkathayam Thiyyas lies in the Tian Shan mountain regions near Kazakhstan’s border. If such a connection exists, one could further investigate whether any Shamanistic spiritual traditions persisted there.

This topic is being set aside for now. However, when examining similarities in language words, it becomes clear that the ornamental design of a language, its words, the structure of its scripts, the sound of its scripts, and their visual form are distinct aspects. It is worth noting that each of these aspects may be the contribution of different groups, individuals, or even advanced technological or intellectual processes.

Next, I will discuss the two distinctly different social structures created by different languages. After that, I understand that this writing will return to the soil of northern Malabar.

5. The depth, expanse, and origin of Indian nationalism and Hindu tradition in post-1947 India

Imagine a lorry with a National Permit (NP) from Himachal Pradesh, loaded with apples, traveling to Cape Comorin (Kanyakumari) in Tamil Nadu. The driver knows the route well, having traveled it multiple times. However, he doesn’t mentally map out the entire 3,000-kilometer journey. Instead, he might think about potential challenges at key points along the way.

As the lorry moves forward, the driver focuses on what lies immediately ahead, navigating based on road conditions and turns while letting what’s behind fade from his mind. He steers, brakes, and accelerates as needed, sometimes taking detours when required.

This imagery is used to illustrate the approach of this writing. The direction of the writing often takes shape based on where it stands at a given moment. Having written over 30 books in English on various topics, this path is familiar to me. Each new piece of writing brings greater precision to the ideas.

However, during the writing process, two distinct mental experiences often emerge:

A sudden insight or revelation about certain matters, arising spontaneously in the mind.

A compulsion to deeply analyze subtle aspects that were previously unconsidered.

These two experiences need to be addressed here. There’s no rush to speed through this writing. A private bus traveling the short distance from Kozhikode to Kundootti must adhere to precise timing, where every minute is valuable. In contrast, an NP lorry traveling from Himachal Pradesh to Cape Comorin has no such need for minute-by-minute precision.

This writing is similar—it covers a vast distance without the need for meticulous timing.

A few days ago, I stumbled upon something intriguing about the development of Hindi. It appears that Christian missionaries from foreign lands played a significant role in its growth. Upon closer examination, this seems to hold true.

I lack the authoritative knowledge to write about this in depth. However, a general understanding has emerged.

Christian missionaries from Britain, continental Europe, and America worked to develop the rudimentary languages spoken by people across this subcontinent. They did this by creating scripts for these languages and importing thousands of Sanskrit words into them, as if pouring water from a vessel.

The literary language known as Hindustani, it seems, originally used Persian or Arabic scripts, along with regional scripts like Kaithi.

When the English East India Company sought to elevate the intellectual level of the people in its territories, Lord Macaulay recommended spreading the English language widely. However, local social leaders opposed this, advocating instead for blending Sanskrit with regional dialects to develop those languages and denying people the opportunity to learn English. Some even argued for using Arabic instead.

Upon investigation, it appears true that Christian missionaries were instrumental in developing Hindi. This raises a question: Why didn’t these missionaries teach English to the lower-class people who converted to their faith? Instead, they developed rudimentary languages, infused them with Sanskrit, and created dictionaries for them—an effort that, in hindsight, seems astonishing.

Several thoughts come to mind in this context.

First, the English East India Company did not permit such missionary activities in its territories. However, a vast area of the South Asian subcontinent was outside Company rule. The actual extent of British India can be seen in the map provided on the next page. In regions outside this control, missionaries likely faced fewer restrictions in conducting their work.

Rev. Samuel Mateer, in the Travancore State Manual (page 705), wrote about the attitude of a British Resident in Travancore toward missionary efforts:

Quote: “We soon discovered that the agent of our Christian land, although a Scotchman attached as he said to the Church of England and her services, was much opposed to missionary effort, and more fearful than were the Brahmins respecting the effects of evangelical religion… his ideas concerning our character and intentions were more alarming, absurd and exaggerated, than were those of others who had come into contact with our institutions.”

Summary: The British Resident was more opposed to missionary activities than even the Brahmins… His views about the missionaries’ character and intentions were extremely alarming, absurd, and exaggerated.

Many of these Christian missionaries were Scottish, Irish, or continental Europeans, who may have harbored a subtle resentment or rivalry toward England. Rev. Samuel Mateer himself was Irish. These groups likely had little interest in seeing the influence of English or England grow. Yet, it must be said that they shone in the natural brilliance of England’s glory.

The second point is that if English were to spread among the lower classes, it could upend society entirely. The downtrodden would rise like a plateau. Society would grow in ways unimaginable to traditional European Christianity, potentially fostering a highly disciplined society even without religion. Christianity itself might become redundant. Local Christian evangelists would likely have no interest in such an outcome. In Christianity, the concept of the shepherd and the flock exists, and for newly emerging Christian priests (the shepherds), societal respect and the subservience of the flock would be essential.

The third point is that conducting gospel preaching, communal singing, and group prayers in the everyday language of the lower classes is the simplest, most efficient, and effective method for religious work.

The fourth point is that traditional landlord families would face a significant dilemma in dealing with a slave class that speaks English. An English-speaking slave class could interact with the English without showing subservience, which would be like scattering a cluster bomb in the social order. That these landlord families would oppose Christian missionary activities is also a reality.

However, the vocabulary in rudimentary languages would be extremely limited. For people in a small world, a few words suffice for communication. In English, it’s believed that a thousand words are enough for a group to discuss most matters.

The need for an extensive vocabulary arises when discussing technical matters, politics, law, scriptures, vehicles like airplanes, maritime navigation, medical knowledge, mathematics, thermodynamics, chemistry, botany, zoology, geology, meteorology, culinary arts, poetry, literature, cinema, large-scale commerce, and more.

Yet, for nearly 99% of the population in South Asia at that time, there was no need to think or speak about such matters. In the 1960s and 70s, in Devarkovil, the conversations of local people, as I observed, revolved around trivial matters. Many were illiterate, did not read newspapers, and some listened to the radio only to check the prices of coconut, pepper, or areca nut at Kozhikode’s Valiyangadi market.

The question of where to import scripts and vocabulary for such rudimentary languages must have been seriously considered by Christian missionaries and local reformist social activists. It seems they decided to draw from Sanskrit. When Sanskrit words were poured into the many rudimentary languages of the northern subcontinent, these languages likely developed a collective affinity. This, I believe, is what became modern Hindi. It seems to have been blended into around 19 languages, though I’m not certain.

Moreover, the historical association of Arabic or Persian scripts with Islam may have sparked mild or significant opposition among Brahmins. Importing Devanagari (Sanskrit script) might have been a way to erase this Arabic influence. Brahmins and their associates likely saw this as safer than allowing the lower classes to learn English.

When examining languages like Malayalam, Telugu, Kannada, Odia, Bengali, Hindi, and Punjabi across the subcontinent, it seems that Christian missionaries were largely responsible for infusing them with a Sanskrit overlay and vocabulary.

This, I believe, is the reality behind what is commonly perceived today as Indian nationalism and Hindu tradition.

The reason Malabari Malayalam was not heavily influenced by Sanskrit words could be that it lacked official support in British Malabar, and movements from Travancore defined it as a crude, tribal language. However, it seems they may have used elements of Malabari to develop Malayalam in Travancore.

As the lorry moves forward, the driver focuses on what lies immediately ahead, navigating based on road conditions and turns while letting what’s behind fade from his mind. He steers, brakes, and accelerates as needed, sometimes taking detours when required.

This imagery is used to illustrate the approach of this writing. The direction of the writing often takes shape based on where it stands at a given moment. Having written over 30 books in English on various topics, this path is familiar to me. Each new piece of writing brings greater precision to the ideas.

However, during the writing process, two distinct mental experiences often emerge:

A sudden insight or revelation about certain matters, arising spontaneously in the mind.

A compulsion to deeply analyze subtle aspects that were previously unconsidered.

These two experiences need to be addressed here. There’s no rush to speed through this writing. A private bus traveling the short distance from Kozhikode to Kundootti must adhere to precise timing, where every minute is valuable. In contrast, an NP lorry traveling from Himachal Pradesh to Cape Comorin has no such need for minute-by-minute precision.

This writing is similar—it covers a vast distance without the need for meticulous timing.

A few days ago, I stumbled upon something intriguing about the development of Hindi. It appears that Christian missionaries from foreign lands played a significant role in its growth. Upon closer examination, this seems to hold true.

I lack the authoritative knowledge to write about this in depth. However, a general understanding has emerged.

Christian missionaries from Britain, continental Europe, and America worked to develop the rudimentary languages spoken by people across this subcontinent. They did this by creating scripts for these languages and importing thousands of Sanskrit words into them, as if pouring water from a vessel.

The literary language known as Hindustani, it seems, originally used Persian or Arabic scripts, along with regional scripts like Kaithi.

When the English East India Company sought to elevate the intellectual level of the people in its territories, Lord Macaulay recommended spreading the English language widely. However, local social leaders opposed this, advocating instead for blending Sanskrit with regional dialects to develop those languages and denying people the opportunity to learn English. Some even argued for using Arabic instead.

Upon investigation, it appears true that Christian missionaries were instrumental in developing Hindi. This raises a question: Why didn’t these missionaries teach English to the lower-class people who converted to their faith? Instead, they developed rudimentary languages, infused them with Sanskrit, and created dictionaries for them—an effort that, in hindsight, seems astonishing.

Several thoughts come to mind in this context.

First, the English East India Company did not permit such missionary activities in its territories. However, a vast area of the South Asian subcontinent was outside Company rule. The actual extent of British India can be seen in the map provided on the next page. In regions outside this control, missionaries likely faced fewer restrictions in conducting their work.

Rev. Samuel Mateer, in the Travancore State Manual (page 705), wrote about the attitude of a British Resident in Travancore toward missionary efforts:

Quote: “We soon discovered that the agent of our Christian land, although a Scotchman attached as he said to the Church of England and her services, was much opposed to missionary effort, and more fearful than were the Brahmins respecting the effects of evangelical religion… his ideas concerning our character and intentions were more alarming, absurd and exaggerated, than were those of others who had come into contact with our institutions.”

Summary: The British Resident was more opposed to missionary activities than even the Brahmins… His views about the missionaries’ character and intentions were extremely alarming, absurd, and exaggerated.

Many of these Christian missionaries were Scottish, Irish, or continental Europeans, who may have harbored a subtle resentment or rivalry toward England. Rev. Samuel Mateer himself was Irish. These groups likely had little interest in seeing the influence of English or England grow. Yet, it must be said that they shone in the natural brilliance of England’s glory.

The second point is that if English were to spread among the lower classes, it could upend society entirely. The downtrodden would rise like a plateau. Society would grow in ways unimaginable to traditional European Christianity, potentially fostering a highly disciplined society even without religion. Christianity itself might become redundant. Local Christian evangelists would likely have no interest in such an outcome. In Christianity, the concept of the shepherd and the flock exists, and for newly emerging Christian priests (the shepherds), societal respect and the subservience of the flock would be essential.

The third point is that conducting gospel preaching, communal singing, and group prayers in the everyday language of the lower classes is the simplest, most efficient, and effective method for religious work.

The fourth point is that traditional landlord families would face a significant dilemma in dealing with a slave class that speaks English. An English-speaking slave class could interact with the English without showing subservience, which would be like scattering a cluster bomb in the social order. That these landlord families would oppose Christian missionary activities is also a reality.

However, the vocabulary in rudimentary languages would be extremely limited. For people in a small world, a few words suffice for communication. In English, it’s believed that a thousand words are enough for a group to discuss most matters.

The need for an extensive vocabulary arises when discussing technical matters, politics, law, scriptures, vehicles like airplanes, maritime navigation, medical knowledge, mathematics, thermodynamics, chemistry, botany, zoology, geology, meteorology, culinary arts, poetry, literature, cinema, large-scale commerce, and more.

Yet, for nearly 99% of the population in South Asia at that time, there was no need to think or speak about such matters. In the 1960s and 70s, in Devarkovil, the conversations of local people, as I observed, revolved around trivial matters. Many were illiterate, did not read newspapers, and some listened to the radio only to check the prices of coconut, pepper, or areca nut at Kozhikode’s Valiyangadi market.

The question of where to import scripts and vocabulary for such rudimentary languages must have been seriously considered by Christian missionaries and local reformist social activists. It seems they decided to draw from Sanskrit. When Sanskrit words were poured into the many rudimentary languages of the northern subcontinent, these languages likely developed a collective affinity. This, I believe, is what became modern Hindi. It seems to have been blended into around 19 languages, though I’m not certain.

Moreover, the historical association of Arabic or Persian scripts with Islam may have sparked mild or significant opposition among Brahmins. Importing Devanagari (Sanskrit script) might have been a way to erase this Arabic influence. Brahmins and their associates likely saw this as safer than allowing the lower classes to learn English.

When examining languages like Malayalam, Telugu, Kannada, Odia, Bengali, Hindi, and Punjabi across the subcontinent, it seems that Christian missionaries were largely responsible for infusing them with a Sanskrit overlay and vocabulary.

This, I believe, is the reality behind what is commonly perceived today as Indian nationalism and Hindu tradition.

The reason Malabari Malayalam was not heavily influenced by Sanskrit words could be that it lacked official support in British Malabar, and movements from Travancore defined it as a crude, tribal language. However, it seems they may have used elements of Malabari to develop Malayalam in Travancore.

6. On the Concept of a Fundamental Script

As I write, navigating through the wilderness where light and darkness flicker, like rowing a simple raft through a wild stream, rising and falling with the waves, soaked and dried by turns, I mentioned in the previous post two thoughts that surfaced in my mind.

[Note: A few words about the poetic phrasing used above. The expression “light and darkness” is likely a form of plagiarism from a well-known poem I came across some time ago, though I can’t recall its title. “Plagiarism” refers to literary theft or borrowing. The term kettumaram is the Malayalam equivalent of a raft. The rest of the words emerged naturally from the imagery in my mind. I hope to write later about the emotions words evoke, though I’m unsure if that will happen. End of Note]

The first point has already been elaborated.

The second point is this:

Quote: “A compulsion to deeply analyze subtle matters previously unconsidered arises in the mind.”

The thought that emerged is about how scripts are created.

Creating an alternative set of scripts for the Malayalam language, which is currently in use, is not difficult. One could assign new symbols to sounds like a, ā, i, ī, etc. A completely new set of scripts for the 52 letters and their conjuncts could be devised. Even for a language without its own scripts but sharing similarities with Sanskrit, Tamil, Kannada, or Malayalam, creating a unique script set would require some effort but is not particularly challenging.

However, this would merely be a form of plagiarism. Claiming that Malayalam has its own script set lacks substantial prestige. This is because using something crafted in another grand workshop without giving attribution and presenting it as an original creation feels slightly flawed.

This is where a subtle thought arose in my mind.

How might a new set of scripts (an alphabet) be created?

Consider this simple spoken phrase:

“Nee konduva.”

This could be more precisely “Nee kondu varu” (Come with it).

But as a raw sound, it might be heard as “Neekonduva.”

How would a people with no knowledge of scripts transcribe such a sound into a script?

In the process of creating a script from mere sound, it might be done like this:

Nee gets one symbol: Ò

Ko gets another: ê

Nduva gets a third: œ

Thus, the sound Neekonduva could be written as Òêœ.

However, if distinct symbols were assigned to every unique sound component, thousands of symbols might be needed. While I’m not saying it’s exactly like Chinese scripts, which reportedly number 5,000–7,000, the principle is similar.

In Sanskrit, scripts were created by combining the sound nee with na and an ī sound. From the tens of thousands of sounds in spoken language, certain fundamental sounds were identified and used to create alphabets.

To create a script set for complex human speech sounds, one must identify these fundamental sounds, understand related common sounds, define their specific forms (ā, i, ī, u, ū, au), and assign corresponding sounds.

This is a monumental task. Ordinarily, only a few individuals or groups with exceptional mental strength, vast imagination, persistent effort, and deep commitment could accomplish this. Alternatively, it feels possible that an advanced technological tool was involved.

This kind of creation is not something that a group of mediocre minds could achieve by running a language laboratory.

Many technical aspects of this creation process come to mind, but I cannot delve into them now.

I am unaware of what linguistic scholars know about script creation. As I lack this knowledge, I’m noting what came to my mind.

I cannot venture into what linguistics says about the history of English scripts. But consider this:

The phrase “Ivide kondu varoo” (Bring here) might be heard as “Ividekonduvaroo.”

In English, this becomes “Bring here,” though it’s typically said as “Bring it here,” “Bring him here,” or “Bring them here.”

Understand that without scripts, these are mere sounds. For example, Bring it here might sound like “Bringgithya” or similar.

Creating an alphabet by hearing and understanding this sound and countless others is a complex task.

However, it seems unlikely that an alphabet like a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, o could be created by merely hearing sounds.

Instead, it requires broad, external, and structured thinking. Simply hearing, observing, touching, shouting, or singing the word bring wouldn’t naturally lead to imagining it as b r i n g.

In reality, creating such a fundamental script set likely requires planning and coding beyond the language process itself.

This leads to the concept of a fundamental script. It can be understood that the scripts of each language were created by assigning different symbols or forms to a fundamental script set, defining their interconnections, and crafting them through relatively simple effort.

What must be considered here is that the sounds of scripts in Sanskrit and Tamil are related. Moreover, the way scripts are combined to form words shows similarities. This suggests that both were derived from the same fundamental script set.

However, English is different. It seems to have been derived from a different fundamental script set.

Additionally, note that English has only 26 letters, while Malayalam has 52, plus numerous conjuncts. Chinese reportedly has 5,000–7,000 characters. This is often discussed as a limitation of English and a strength of Asian feudal languages. However, I believe the ability to simplify complex matters to the most basic level is a sign of a society’s great intellectual capacity.

Notice that in English, symbols like ā, i, ī, u, ū, au, which stretch, compress, twist, or modify letter forms and sounds, are absent in standard speech and writing. However, I understand that phonetics is used in linguistics when teaching English to non-native speakers.

(This has become a complex topic today. I understand that those fluent in English don’t need phonetics, but it’s worth examining whether it significantly benefits those who lack this fluency.)

What must be noted is that there need not be a connection between a script and the ornamental design of a language. Both feudal and egalitarian languages might derive their scripts from the same fundamental script set.

[Note: A few words about the poetic phrasing used above. The expression “light and darkness” is likely a form of plagiarism from a well-known poem I came across some time ago, though I can’t recall its title. “Plagiarism” refers to literary theft or borrowing. The term kettumaram is the Malayalam equivalent of a raft. The rest of the words emerged naturally from the imagery in my mind. I hope to write later about the emotions words evoke, though I’m unsure if that will happen. End of Note]

The first point has already been elaborated.

The second point is this:

Quote: “A compulsion to deeply analyze subtle matters previously unconsidered arises in the mind.”

The thought that emerged is about how scripts are created.

Creating an alternative set of scripts for the Malayalam language, which is currently in use, is not difficult. One could assign new symbols to sounds like a, ā, i, ī, etc. A completely new set of scripts for the 52 letters and their conjuncts could be devised. Even for a language without its own scripts but sharing similarities with Sanskrit, Tamil, Kannada, or Malayalam, creating a unique script set would require some effort but is not particularly challenging.

However, this would merely be a form of plagiarism. Claiming that Malayalam has its own script set lacks substantial prestige. This is because using something crafted in another grand workshop without giving attribution and presenting it as an original creation feels slightly flawed.

This is where a subtle thought arose in my mind.

How might a new set of scripts (an alphabet) be created?

Consider this simple spoken phrase:

“Nee konduva.”

This could be more precisely “Nee kondu varu” (Come with it).

But as a raw sound, it might be heard as “Neekonduva.”

How would a people with no knowledge of scripts transcribe such a sound into a script?

In the process of creating a script from mere sound, it might be done like this:

Nee gets one symbol: Ò

Ko gets another: ê

Nduva gets a third: œ

Thus, the sound Neekonduva could be written as Òêœ.

However, if distinct symbols were assigned to every unique sound component, thousands of symbols might be needed. While I’m not saying it’s exactly like Chinese scripts, which reportedly number 5,000–7,000, the principle is similar.

In Sanskrit, scripts were created by combining the sound nee with na and an ī sound. From the tens of thousands of sounds in spoken language, certain fundamental sounds were identified and used to create alphabets.

To create a script set for complex human speech sounds, one must identify these fundamental sounds, understand related common sounds, define their specific forms (ā, i, ī, u, ū, au), and assign corresponding sounds.

This is a monumental task. Ordinarily, only a few individuals or groups with exceptional mental strength, vast imagination, persistent effort, and deep commitment could accomplish this. Alternatively, it feels possible that an advanced technological tool was involved.

This kind of creation is not something that a group of mediocre minds could achieve by running a language laboratory.

Many technical aspects of this creation process come to mind, but I cannot delve into them now.

I am unaware of what linguistic scholars know about script creation. As I lack this knowledge, I’m noting what came to my mind.

I cannot venture into what linguistics says about the history of English scripts. But consider this:

The phrase “Ivide kondu varoo” (Bring here) might be heard as “Ividekonduvaroo.”

In English, this becomes “Bring here,” though it’s typically said as “Bring it here,” “Bring him here,” or “Bring them here.”

Understand that without scripts, these are mere sounds. For example, Bring it here might sound like “Bringgithya” or similar.

Creating an alphabet by hearing and understanding this sound and countless others is a complex task.

However, it seems unlikely that an alphabet like a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, o could be created by merely hearing sounds.

Instead, it requires broad, external, and structured thinking. Simply hearing, observing, touching, shouting, or singing the word bring wouldn’t naturally lead to imagining it as b r i n g.

In reality, creating such a fundamental script set likely requires planning and coding beyond the language process itself.

This leads to the concept of a fundamental script. It can be understood that the scripts of each language were created by assigning different symbols or forms to a fundamental script set, defining their interconnections, and crafting them through relatively simple effort.

What must be considered here is that the sounds of scripts in Sanskrit and Tamil are related. Moreover, the way scripts are combined to form words shows similarities. This suggests that both were derived from the same fundamental script set.

However, English is different. It seems to have been derived from a different fundamental script set.

Additionally, note that English has only 26 letters, while Malayalam has 52, plus numerous conjuncts. Chinese reportedly has 5,000–7,000 characters. This is often discussed as a limitation of English and a strength of Asian feudal languages. However, I believe the ability to simplify complex matters to the most basic level is a sign of a society’s great intellectual capacity.

Notice that in English, symbols like ā, i, ī, u, ū, au, which stretch, compress, twist, or modify letter forms and sounds, are absent in standard speech and writing. However, I understand that phonetics is used in linguistics when teaching English to non-native speakers.

(This has become a complex topic today. I understand that those fluent in English don’t need phonetics, but it’s worth examining whether it significantly benefits those who lack this fluency.)

What must be noted is that there need not be a connection between a script and the ornamental design of a language. Both feudal and egalitarian languages might derive their scripts from the same fundamental script set.

7. On the integration into a grand Vedic Indian culture

Readers may have noticed that this writing has not yet begun to narrate history. Before delving into history, the effort here is to clearly define the various social contexts and communities of this subcontinent from its historical period onward. This is necessary to clarify whose history, which society, and which region’s history is being written. Without this clarity, merely listing historical events and the actions of those who lived through them would be like studying the ocean by only observing its surface, which feels inadequate.

The discussion of the various backgrounds of the Marumakkathayam Thiyyas of North Malabar has wandered deep into the wilderness. However, the point where this writing now stands, and the direction of the writer’s intent, has reached a place entirely unforeseen. The prevailing claims about the shared heritage of the newly formed nation called India are now sparking a desire to confront them. Yet, I, the writer, am not someone who relishes confrontations. Still, I cannot refrain from expressing what has arisen in my mind.

I lack the profound knowledge to elaborate on these matters deeply. Moreover, I have no capacity to dive into the depths of such topics, as only those proficient in languages like Sanskrit, Pali, Magadhi, Ardhamagadhi, Prakrit, Hindi, Urdu, Hindustani, Arabic, and Persian could truly understand the reality of what I am about to say. I am not versed in any of these languages.

What I am about to express is a thought that has taken root in my mind. Such thoughts must be voiced because the writings and claims of those who profess scholarly authority often reflect their personal interests, patriotism, communal biases, political leanings, or job security. If these influences are stripped away and the subcontinent’s matters are written with clarity, the picture that emerges might be very different.

It is often said:

“For thousands of years, Hindus have lived in this subcontinent. At their helm are Brahmins, with lower castes beneath them. Their ancient language, Sanskrit, is one of great sophistication. Using the four Vedas, mantras, tantras, Upanishads, Brahmanas, Smritis, and Shrutis in daily life, they led a highly refined existence. These are the ancestors of today’s people in this subcontinent.”

This is the narrative propagated by many with patriotic fervor, used to bolster their sense of pride and identity.

However, I cannot recall ever feeling that this narrative holds true.

Wherever British rule was established, they would investigate whether any ancient traditions lay buried in obscurity. When British India was established in parts of South Asia, they sensed that the region might have had significant ancient traditions. Yet, the vast majority of the subcontinent’s population consisted of various levels of subjugated people. Nowhere was it explicitly documented that they were slaves, and this remains the case in modern India.

It seems that British rule was responsible for recovering, preserving, studying, and introducing to the world many Sanskrit palm-leaf manuscripts that were nearly forgotten in Brahmin households and other places. In other words, the British administration revitalized and nurtured a fading Sanskrit tradition that had arrived in the subcontinent from somewhere else.

In the northern parts of South Asia, ordinary people likely spoke various rudimentary languages. These may have been influenced by ancient languages like Pali, Magadhi, Ardhamagadhi, or Prakrit. However, maharajas, petty kings, large landowners, and others might have spoken Hindustani or similar languages. Brahmins may have had a limited connection with Sanskrit, with some involved in maintaining temples as a hereditary practice.

Foreign-origin Muslim rulers and their families likely adopted much of the opulent demeanor of local elites. Many of them married into prominent non-Muslim local families.

To say that kings ruled does not mean they operated schools, hospitals, legal systems, courts, or welfare programs. Rather, their primary agenda was to keep the various societal strata suppressed and utilize them for the benefit of the elite.

It seems unlikely that there is any significant connection between the Sanskrit-speaking culture and people that emerged thousands of years ago in Central Asia and the people the British encountered in this subcontinent.

Firstly, most people had no knowledge of Sanskrit, and they were denied access to Brahmin temples.

Some Brahmins may have had considerable expertise in Sanskrit traditions, but this was likely limited to a small group, often those associated with temples. Their primary agenda was likely to maintain the societal hierarchy of subjugation.

Brahmins did not allow others into their religion. Sharing their spiritual status with the lower classes was considered highly dangerous, and they were well aware of this. Such folly was only undertaken by certain Christian movements and Islam.

Sanskrit, with its Devanagari script, vast vocabulary, Vedic literature, mantras, tantras, and astrological texts, is well-documented. Similar ancient traditions exist in various parts of the world, such as ancient Egypt, though the fate of those people is unknown.

There is no basis to claim a connection between the Vedic-era people and those the British encountered in this subcontinent. Such claims would be an insult to the Vedic culture’s people.

It is unclear which fundamental script served as the basis for creating Sanskrit or Devanagari scripts. However, those who created the fundamental script must have been intellectual giants. Whether they were the ones who sustained Vedic culture is uncertain, as Vedic culture itself likely has an even more ancient origin. It could be said that the Vedic people derived their scripts from an earlier fundamental script.

It is said that the four Vedas were not created simultaneously, though the basis for this claim is unclear. Creating the Vedas, mantras, and tantras required extraordinary capabilities, possibly even advanced technology.

Moreover, mantras, tantras, and astrology exist in the ancient traditions of many parts of the world. How these were interconnected in antiquity is unknown, but there are notable similarities. For instance, there are many parallels between European witchcraft and the sorcery practices of this subcontinent. However, those traditionally believed to practice sorcery in this subcontinent were often marginalized lower-class groups, so they may not resemble European witches in appearance or personality.

Christian missionaries from Britain, continental Europe, and America worked to uplift many of the subcontinent’s lower classes, both through conversion and otherwise.

Brahmins would not share their Sanskrit knowledge, language, or scripts with the lower classes. If these were taken from them, the lower classes could appropriate them, build temples, study the Vedas, use mantras, read Sanskrit literature, compose Sanskrit poetry, and study astrology. Some might even rise to become spiritual gurus.

The Vedas, Upanishads, mantras, Smritis, and astrology are not mere trivialities. However, it is unlikely that they were created by Brahmins or the ancestors of any specific group in modern India. Given that individuals today are connected to millions of ancestors from 300–400 years ago, and potentially billions from 4,000 years ago or more, such claims are untenable.

It seems unlikely that Brahmins had the capacity to create the Vedas or mantras, nor is it likely they knew how these were made. However, they somehow came into possession of these and preserved them with care, quality, and exclusivity for centuries. Their loyalty and commitment to these traditions are noteworthy. Whether those who later acquired these traditions from them maintained the same loyalty and commitment is uncertain.

The British administration likely found that 99% of the subcontinent’s people were illiterate lower classes, speaking various distinct languages among themselves. When missionaries from Britain and Europe planned to uplift these people, they likely realized the need for common languages. At the same time, they may have decided not to promote the language of the nearby British-Indian administration, for reasons mentioned earlier.

This likely led to thousands or tens of thousands of Sanskrit words being infused into the numerous rudimentary languages of the northern subcontinent, along with Sanskrit scripts. As a result, these languages began to show similarities. For example, if modern Malayalam were written in Hindi scripts, a degree of affinity between the two languages might emerge within a few decades. While modern Malayalam has tens of thousands of words, the rudimentary languages of that time likely had only a few hundred.

As Sanskrit entered these languages, knowledge of the Vedas, Upanishads, mantras, Smritis, and astrology gradually seeped into the minds of those who spoke, wrote, and read these languages.

Thus, everyone began to integrate into a grand Vedic Indian culture.

Please Note: The above topic has been approached very simply. A deeper exploration would require addressing many more details, including the case of Tamil, which cannot be covered here due to limitations.

The discussion of the various backgrounds of the Marumakkathayam Thiyyas of North Malabar has wandered deep into the wilderness. However, the point where this writing now stands, and the direction of the writer’s intent, has reached a place entirely unforeseen. The prevailing claims about the shared heritage of the newly formed nation called India are now sparking a desire to confront them. Yet, I, the writer, am not someone who relishes confrontations. Still, I cannot refrain from expressing what has arisen in my mind.

I lack the profound knowledge to elaborate on these matters deeply. Moreover, I have no capacity to dive into the depths of such topics, as only those proficient in languages like Sanskrit, Pali, Magadhi, Ardhamagadhi, Prakrit, Hindi, Urdu, Hindustani, Arabic, and Persian could truly understand the reality of what I am about to say. I am not versed in any of these languages.

What I am about to express is a thought that has taken root in my mind. Such thoughts must be voiced because the writings and claims of those who profess scholarly authority often reflect their personal interests, patriotism, communal biases, political leanings, or job security. If these influences are stripped away and the subcontinent’s matters are written with clarity, the picture that emerges might be very different.

It is often said:

“For thousands of years, Hindus have lived in this subcontinent. At their helm are Brahmins, with lower castes beneath them. Their ancient language, Sanskrit, is one of great sophistication. Using the four Vedas, mantras, tantras, Upanishads, Brahmanas, Smritis, and Shrutis in daily life, they led a highly refined existence. These are the ancestors of today’s people in this subcontinent.”

This is the narrative propagated by many with patriotic fervor, used to bolster their sense of pride and identity.

However, I cannot recall ever feeling that this narrative holds true.

Wherever British rule was established, they would investigate whether any ancient traditions lay buried in obscurity. When British India was established in parts of South Asia, they sensed that the region might have had significant ancient traditions. Yet, the vast majority of the subcontinent’s population consisted of various levels of subjugated people. Nowhere was it explicitly documented that they were slaves, and this remains the case in modern India.

It seems that British rule was responsible for recovering, preserving, studying, and introducing to the world many Sanskrit palm-leaf manuscripts that were nearly forgotten in Brahmin households and other places. In other words, the British administration revitalized and nurtured a fading Sanskrit tradition that had arrived in the subcontinent from somewhere else.

In the northern parts of South Asia, ordinary people likely spoke various rudimentary languages. These may have been influenced by ancient languages like Pali, Magadhi, Ardhamagadhi, or Prakrit. However, maharajas, petty kings, large landowners, and others might have spoken Hindustani or similar languages. Brahmins may have had a limited connection with Sanskrit, with some involved in maintaining temples as a hereditary practice.

Foreign-origin Muslim rulers and their families likely adopted much of the opulent demeanor of local elites. Many of them married into prominent non-Muslim local families.

To say that kings ruled does not mean they operated schools, hospitals, legal systems, courts, or welfare programs. Rather, their primary agenda was to keep the various societal strata suppressed and utilize them for the benefit of the elite.

It seems unlikely that there is any significant connection between the Sanskrit-speaking culture and people that emerged thousands of years ago in Central Asia and the people the British encountered in this subcontinent.

Firstly, most people had no knowledge of Sanskrit, and they were denied access to Brahmin temples.

Some Brahmins may have had considerable expertise in Sanskrit traditions, but this was likely limited to a small group, often those associated with temples. Their primary agenda was likely to maintain the societal hierarchy of subjugation.

Brahmins did not allow others into their religion. Sharing their spiritual status with the lower classes was considered highly dangerous, and they were well aware of this. Such folly was only undertaken by certain Christian movements and Islam.

Sanskrit, with its Devanagari script, vast vocabulary, Vedic literature, mantras, tantras, and astrological texts, is well-documented. Similar ancient traditions exist in various parts of the world, such as ancient Egypt, though the fate of those people is unknown.