THE NATIVE RACES OF SOUTH AFRICA

THE NATIVE RACES OF SOUTH AFRICA

header #

THE NATIVE RACES OF SOUTH AFRICA

by

GEORGE W. STOW, F.G.S., F.R.G.S.

DOWNLOAD PDF digital book version from here

Along with a Commentary by

VED from VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

Aaradhana, DEVERKOVIL 673508 India

www.victoriainstitutions.com

admn@victoriainstitutions.com

Telegram

by

GEORGE W. STOW, F.G.S., F.R.G.S.

DOWNLOAD PDF digital book version from here

Along with a Commentary by

VED from VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

Aaradhana, DEVERKOVIL 673508 India

www.victoriainstitutions.com

admn@victoriainstitutions.com

Telegram

Last edited by VED on Tue Aug 05, 2025 6:16 pm, edited 5 times in total.

Commentary

co #

COMMENTARY

1. Intro

2. Comparative stance

3. Lowering of the native-English mental stamina

4. What has been missed

5. A most terrific observation

6. How the Bushmen was treated by the native tribes of Africa and by the Boers

7. Serpent worship

8. Irish Link

9. The invisible spirit of Dutch colonial endeavours

10. Islamic demeanour

11. Satanism in feudal languages

12. India overrunning England

13. Slavery in South Asia

14. Native English versus the Boers

15. Bushmen and the Boers

16. Shamanistic spiritual system

17. Bushmen Butchered

18. Bushmen - Refined character

19. Bushmen versus the native African encroachers

20. Effect of language codes

21. BOERS and Hottentots

22. English intervention

23. The entry of various other populations into South Africa

24. African social situation

25. Colonial effect

26. London Missionary Society

27. Miscellaneous

28. Social Engineering

1. Intro

2. Comparative stance

3. Lowering of the native-English mental stamina

4. What has been missed

5. A most terrific observation

6. How the Bushmen was treated by the native tribes of Africa and by the Boers

7. Serpent worship

8. Irish Link

9. The invisible spirit of Dutch colonial endeavours

10. Islamic demeanour

11. Satanism in feudal languages

12. India overrunning England

13. Slavery in South Asia

14. Native English versus the Boers

15. Bushmen and the Boers

16. Shamanistic spiritual system

17. Bushmen Butchered

18. Bushmen - Refined character

19. Bushmen versus the native African encroachers

20. Effect of language codes

21. BOERS and Hottentots

22. English intervention

23. The entry of various other populations into South Africa

24. African social situation

25. Colonial effect

26. London Missionary Society

27. Miscellaneous

28. Social Engineering

Last edited by VED on Wed Dec 06, 2023 4:32 pm, edited 4 times in total.

1

c1 #

Intro

Intro

I had made some observations on what was in the offing with regard to South Africa, in my ancient book March of the Evil Empires; English versus the feudal languages! The initial drafting of this book had been done in the ending months of 1989. However, the book was rewritten and made into its final form only in 2002.

My information on South Africa was quite of the abysmal level in those days. However, I wrote from my own basic perspectives and information on feudal languages. My posture was simply that if the native South African languages do have the codes of pejorative versus ennobling in them, then the nation would move into a diseased state when the nation gets handed over to the native blacks.

Even though what I had claimed was quite powerful, and more or less plausible, the fact remained that my information on Boers, various South African native tribes, their languages &c. was quite minimal. Even though I was aware that it was the native-English who initially had the upper-hand, it seemed a kind of absurdity that the Boers were handed over the political power.

Even now my information on Afrikaans language is an absolute zero. Since most of my writings are connected to what may be mentioned as language codes, feudal languages, pristine-English, codes of reality &c., it is a grave failing in me that I do not know anything about Afrikaans. Especially when I am embarking on a commentary such as this.

At the moment of this writing, I do not know what the popular language among the Whites in South Africa was, whether it was English or Afrikaans. Why I am harping upon language so much is that it has been my observation that language systems are the most powerful encoding that designs a social system. What pristine-English can design would be entirely different from what Afrikaans, Afrikaans-English mixture, native-African languages &c. can design.

When speaking these things about languages in English, if the reader is a native-English individual, he would not get a head or tail of what is being mentioned. However, the fact remains that the native-Englishman does not know what the emotional and thinking process content is, in feudal languages. The very fact that there is such a thing which can be defined as feudal language is there in existence is not seen mentioned in English much.

I cannot deal with the subject of feudal language here. For it is a very huge theme. However, the interested reader can peruse some of my books in this regard:

1. March of the Evil Empires; English versus the feudal languages!

2. Shrouded Satanism in feudal languages!

3. Software codes of mantra, tantra, witchcraft, black magic, evil eye, evil tongue &c.

4. An Impressionistic History of the South Asian Subcontinent

The original writing of item no.4 👆 is in a vernacular of South Asia, for the local people there to read. So, there can be no duplicity about what I am writing in English.

5. What is entering? (into England)

I have done very deep studies on a few books, written during the English colonial rule period in South Asia. They include Malabar Manual by William Logan, Travancore State Manual by V Nagam Aiya, Native Life in Travancore by The REV. SAMUEL MATEER, Castes and tribes of Southern India Vol 1 by Edgar Thurston and Omens and Superstitions of Southern India by Edgar Thurston. On the first four of them I have written commentaries.

I have also done a study of Adolf Hilter’s Mein Kampf and written a commentary plus annotation on this book and brought it out in the name: MEIN KAMPF by Adolf Hitler. - A demystification!

I have mentioned this much to mention that I am not new to these kinds of books and writings. However, this is the first book I have touched upon about Africa or, rather to be precise, about South Africa. There might not be much need to mention that I have had certain impressions about the native peoples of Africa and South Africa in a very vague manner. I was aware of various items like Zanzibar, Slave Trade, West African Squadron of the British Royal Navy, Bushmen, cannibals &c. and such other things. However, there was not much of an information on how the native peoples lived.

I did not have the least bit of idea as to what would come out from this book when I started reading it. Now about this book itself, I need to mention this much. I selected this book for my study due to no specific reason. There were a few others. However, somehow this was the book file (PDF) that appeared at that time to be easy to convert into an editable version in MS Word.

The selection of the book was propitious in one sense. It was that this book literally took me straight into the depths of the Native races’ life experiences. However, the defect with this selection was that it did not deal at all with the Boers versus native-English confrontations in South Africa. It was a location which I was keenly interested in. In fact, I wanted to view how the verbal codes of Dutch language and those of pristine English confronted each other.

When I speak about such a linguistic confrontation, the reader might not understand what I am speaking about. I can easily explain that.

If there is a confrontation between a group of Frenchmen and a group of Englishmen, the simple fact is that it is a confrontation between two groups of human beings. Moreover, they are both White-skinned persons. However, there is a wider defining content in each group. One group speaks and thinks in French. The other in English. This is the vital location where the two groups, though both are human beings, differ. The same is the case when a group of Irishmen or Scots or Welsh persons confront with a group of native-English.

A number of native South African / African tribes or races have been mentioned in this book. From a comprehensive perspective, this book is pro-Bushmen. In fact, South Africa is seen belonging to the Bushmen by ancestral claims. All other claims, both White as well as black stands demolished, as per the information given in this book.

As to the veracity of the contents in this book, I did not find any reason to doubt it.

What is described in this book is terrific and if visualised mentally, the various scenes of barbarity that continuously gets enacted and repeated throughout the book, might given a mental shock to the reader and also appear in his or her dreams as some kind of nightmare scenarios. However, it is doubtful if any reader would try to imagine the incidences in his or her mind.

Talking about barbarity, the fact remains that most of the current-day world is still barbarian. In fact, if one were to remove the luxuries that technology had given to mankind in the last 100 years or so, only the few nations connected to native-English speakers and a few other nations would be seen to be above the social standards of barbarianism.

For instance, if English and the technological devices of the modern ages are removed from South Asia, the population would have not much of a difference from many of the semi-barbarian populations in the world. If English is not there in South Asia, then what would remain would be languages which are very carnivorous. That is, languages which would be used by the stronger class or individual to prey upon or impale the weaker group or individual by mere verbal codes.

My information on South Africa was quite of the abysmal level in those days. However, I wrote from my own basic perspectives and information on feudal languages. My posture was simply that if the native South African languages do have the codes of pejorative versus ennobling in them, then the nation would move into a diseased state when the nation gets handed over to the native blacks.

Even though what I had claimed was quite powerful, and more or less plausible, the fact remained that my information on Boers, various South African native tribes, their languages &c. was quite minimal. Even though I was aware that it was the native-English who initially had the upper-hand, it seemed a kind of absurdity that the Boers were handed over the political power.

Even now my information on Afrikaans language is an absolute zero. Since most of my writings are connected to what may be mentioned as language codes, feudal languages, pristine-English, codes of reality &c., it is a grave failing in me that I do not know anything about Afrikaans. Especially when I am embarking on a commentary such as this.

At the moment of this writing, I do not know what the popular language among the Whites in South Africa was, whether it was English or Afrikaans. Why I am harping upon language so much is that it has been my observation that language systems are the most powerful encoding that designs a social system. What pristine-English can design would be entirely different from what Afrikaans, Afrikaans-English mixture, native-African languages &c. can design.

When speaking these things about languages in English, if the reader is a native-English individual, he would not get a head or tail of what is being mentioned. However, the fact remains that the native-Englishman does not know what the emotional and thinking process content is, in feudal languages. The very fact that there is such a thing which can be defined as feudal language is there in existence is not seen mentioned in English much.

I cannot deal with the subject of feudal language here. For it is a very huge theme. However, the interested reader can peruse some of my books in this regard:

1. March of the Evil Empires; English versus the feudal languages!

2. Shrouded Satanism in feudal languages!

3. Software codes of mantra, tantra, witchcraft, black magic, evil eye, evil tongue &c.

4. An Impressionistic History of the South Asian Subcontinent

The original writing of item no.4 👆 is in a vernacular of South Asia, for the local people there to read. So, there can be no duplicity about what I am writing in English.

5. What is entering? (into England)

I have done very deep studies on a few books, written during the English colonial rule period in South Asia. They include Malabar Manual by William Logan, Travancore State Manual by V Nagam Aiya, Native Life in Travancore by The REV. SAMUEL MATEER, Castes and tribes of Southern India Vol 1 by Edgar Thurston and Omens and Superstitions of Southern India by Edgar Thurston. On the first four of them I have written commentaries.

I have also done a study of Adolf Hilter’s Mein Kampf and written a commentary plus annotation on this book and brought it out in the name: MEIN KAMPF by Adolf Hitler. - A demystification!

I have mentioned this much to mention that I am not new to these kinds of books and writings. However, this is the first book I have touched upon about Africa or, rather to be precise, about South Africa. There might not be much need to mention that I have had certain impressions about the native peoples of Africa and South Africa in a very vague manner. I was aware of various items like Zanzibar, Slave Trade, West African Squadron of the British Royal Navy, Bushmen, cannibals &c. and such other things. However, there was not much of an information on how the native peoples lived.

I did not have the least bit of idea as to what would come out from this book when I started reading it. Now about this book itself, I need to mention this much. I selected this book for my study due to no specific reason. There were a few others. However, somehow this was the book file (PDF) that appeared at that time to be easy to convert into an editable version in MS Word.

The selection of the book was propitious in one sense. It was that this book literally took me straight into the depths of the Native races’ life experiences. However, the defect with this selection was that it did not deal at all with the Boers versus native-English confrontations in South Africa. It was a location which I was keenly interested in. In fact, I wanted to view how the verbal codes of Dutch language and those of pristine English confronted each other.

When I speak about such a linguistic confrontation, the reader might not understand what I am speaking about. I can easily explain that.

If there is a confrontation between a group of Frenchmen and a group of Englishmen, the simple fact is that it is a confrontation between two groups of human beings. Moreover, they are both White-skinned persons. However, there is a wider defining content in each group. One group speaks and thinks in French. The other in English. This is the vital location where the two groups, though both are human beings, differ. The same is the case when a group of Irishmen or Scots or Welsh persons confront with a group of native-English.

A number of native South African / African tribes or races have been mentioned in this book. From a comprehensive perspective, this book is pro-Bushmen. In fact, South Africa is seen belonging to the Bushmen by ancestral claims. All other claims, both White as well as black stands demolished, as per the information given in this book.

As to the veracity of the contents in this book, I did not find any reason to doubt it.

What is described in this book is terrific and if visualised mentally, the various scenes of barbarity that continuously gets enacted and repeated throughout the book, might given a mental shock to the reader and also appear in his or her dreams as some kind of nightmare scenarios. However, it is doubtful if any reader would try to imagine the incidences in his or her mind.

Talking about barbarity, the fact remains that most of the current-day world is still barbarian. In fact, if one were to remove the luxuries that technology had given to mankind in the last 100 years or so, only the few nations connected to native-English speakers and a few other nations would be seen to be above the social standards of barbarianism.

For instance, if English and the technological devices of the modern ages are removed from South Asia, the population would have not much of a difference from many of the semi-barbarian populations in the world. If English is not there in South Asia, then what would remain would be languages which are very carnivorous. That is, languages which would be used by the stronger class or individual to prey upon or impale the weaker group or individual by mere verbal codes.

Last edited by VED on Wed Dec 06, 2023 4:33 pm, edited 2 times in total.

2

c2 #

Comparative stance

Comparative stance

After reading this book, my mind has become loaded with a lot of historical information with regard to mankind and living beings in general and to South Africa in particular. I am not sure as to how I going to use them in this commentary. I need to take a comparative stance. That is to make comparisons with the various incidences and information I have read, with those of South Asia, and with native-English global experiences.

I need to very categorically mention that the native-English, though secluded from very many negative emotional traps and sinister social encodings, are a very foolish and gullible lot in the sense that they are being fooled by the cunning fake affability of the others. They do not have much information on what the world is just beyond the borders of the pristine-English world. They have been led and misled by others on various items to terrific historic traps.

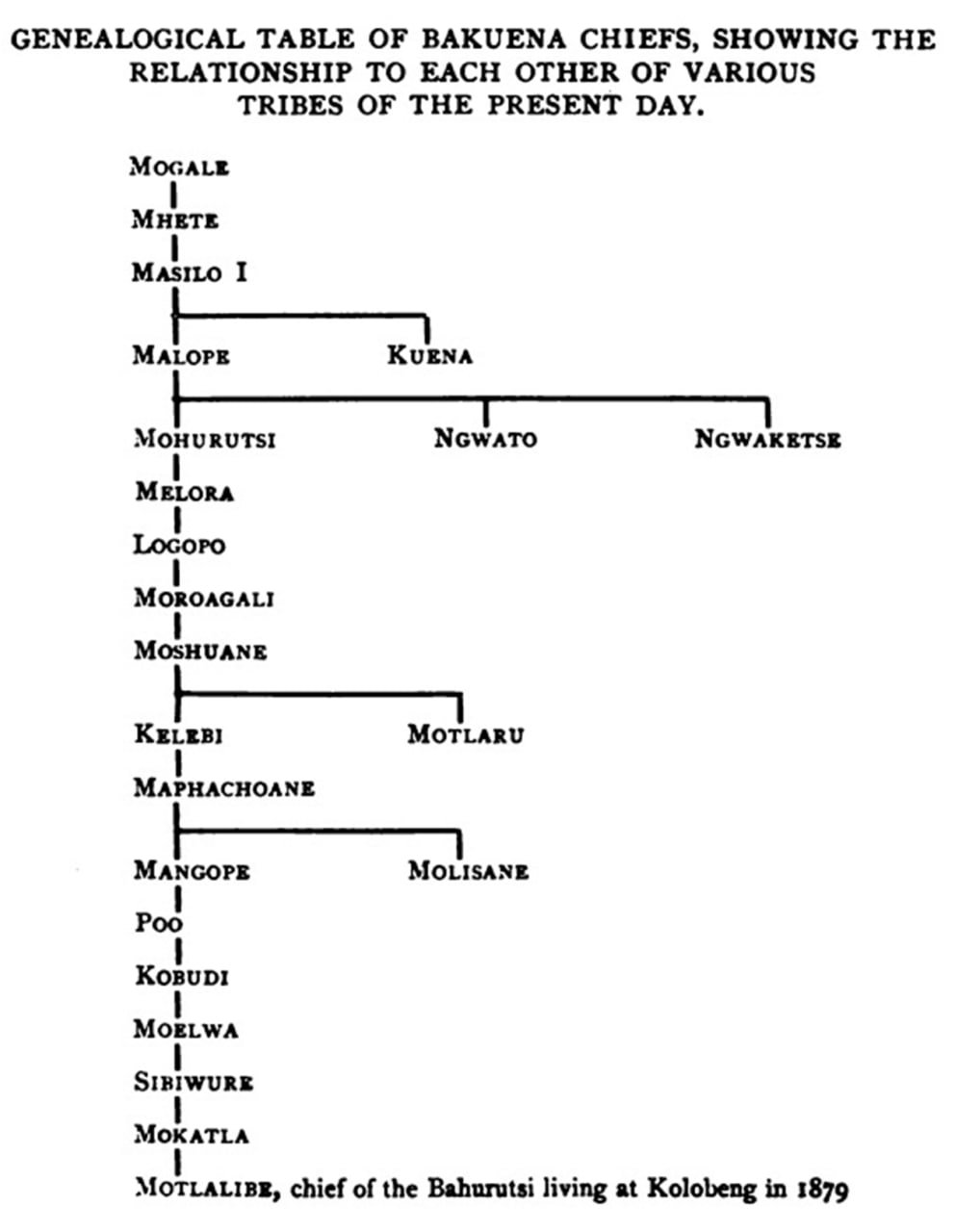

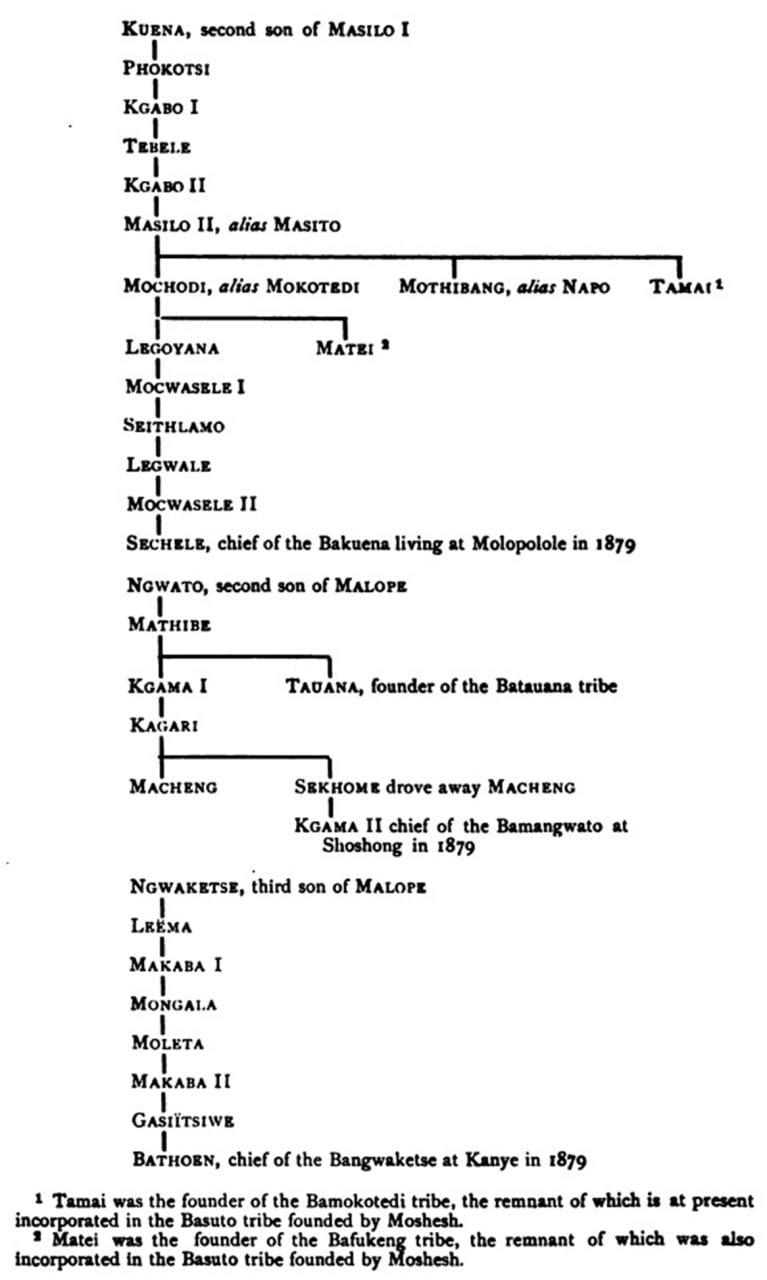

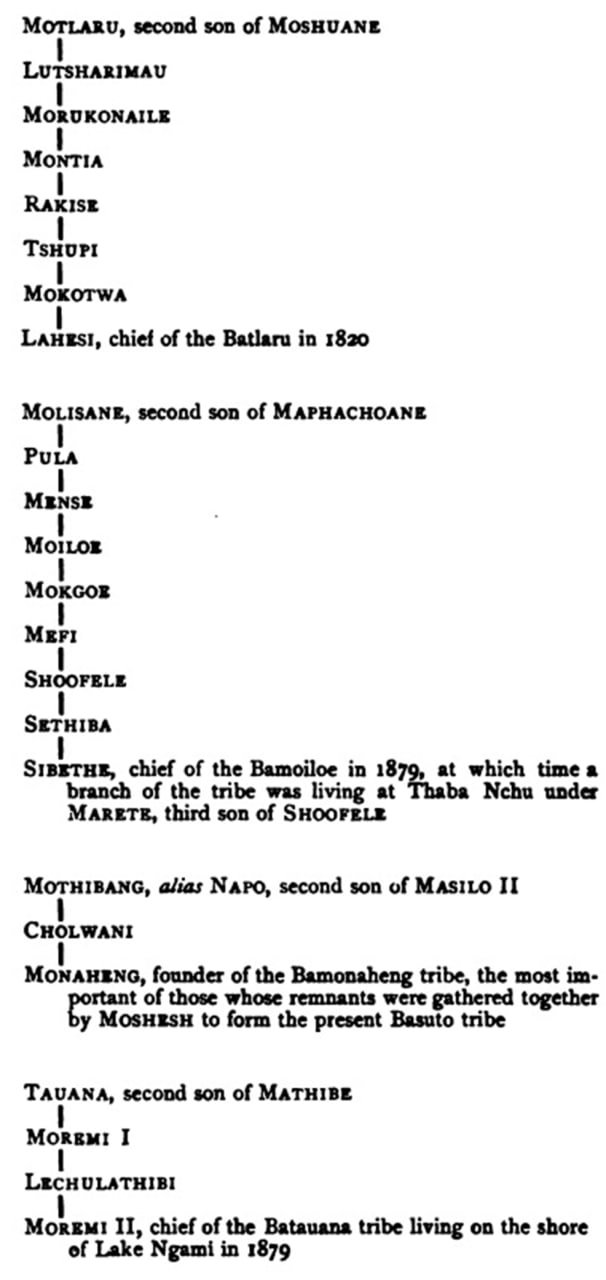

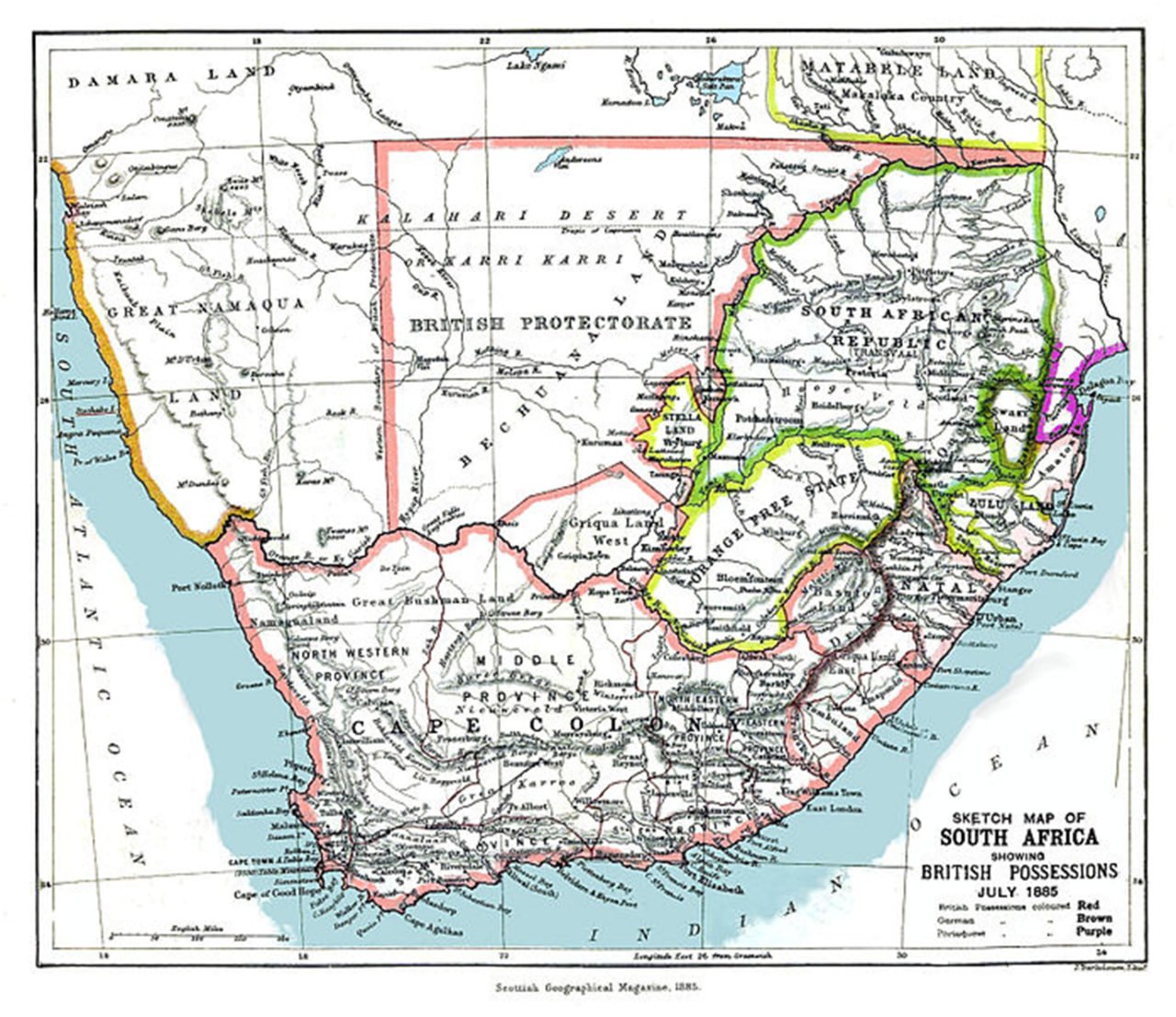

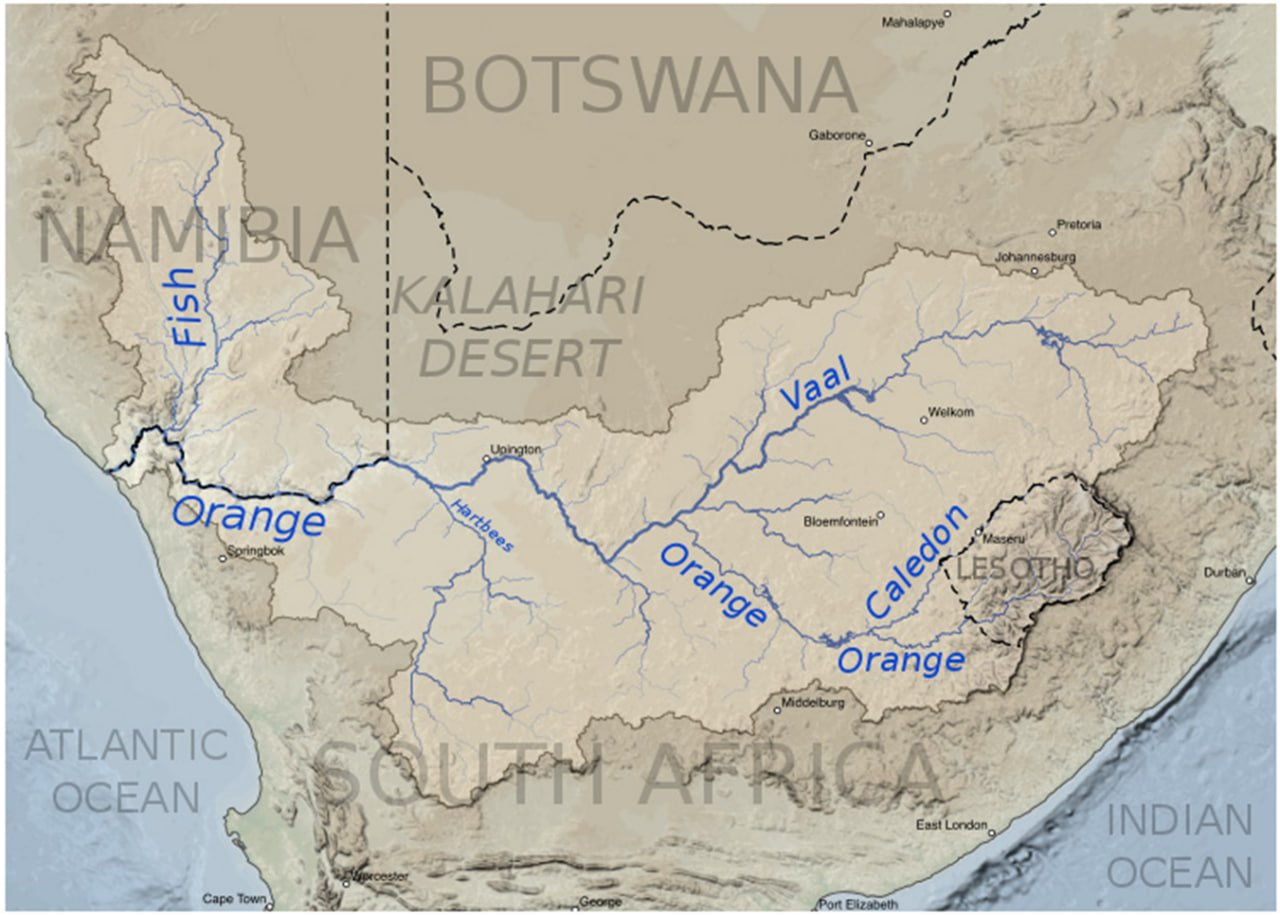

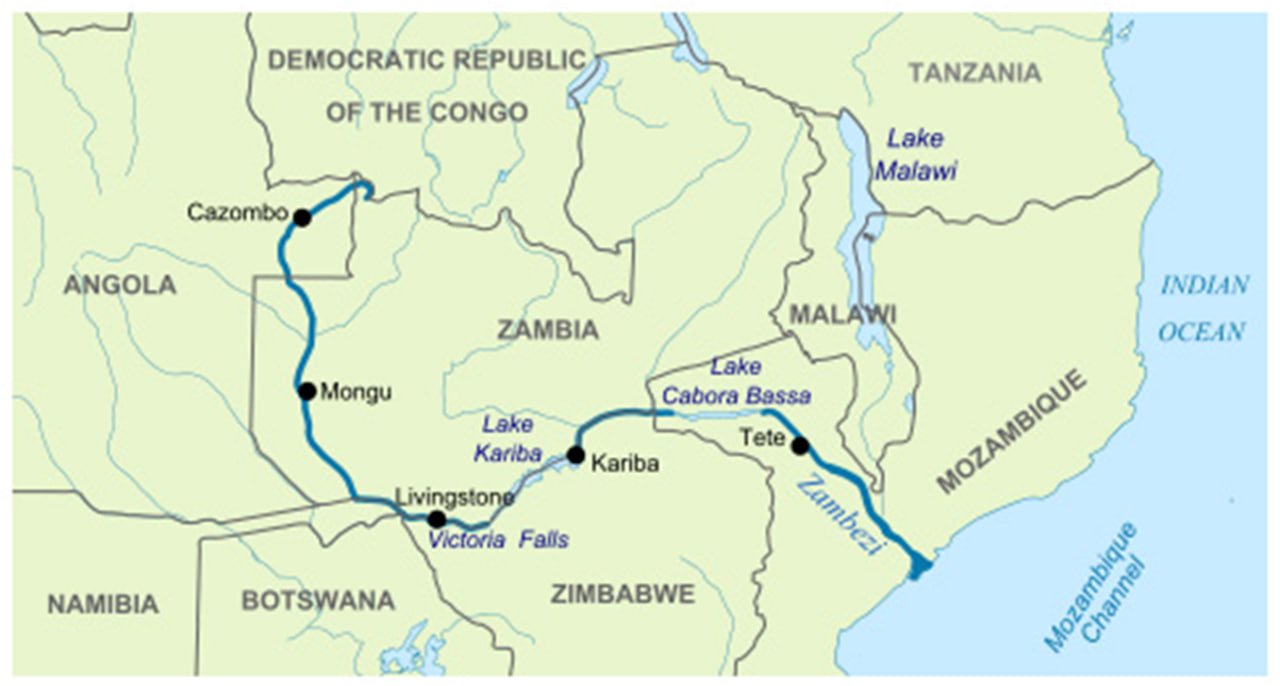

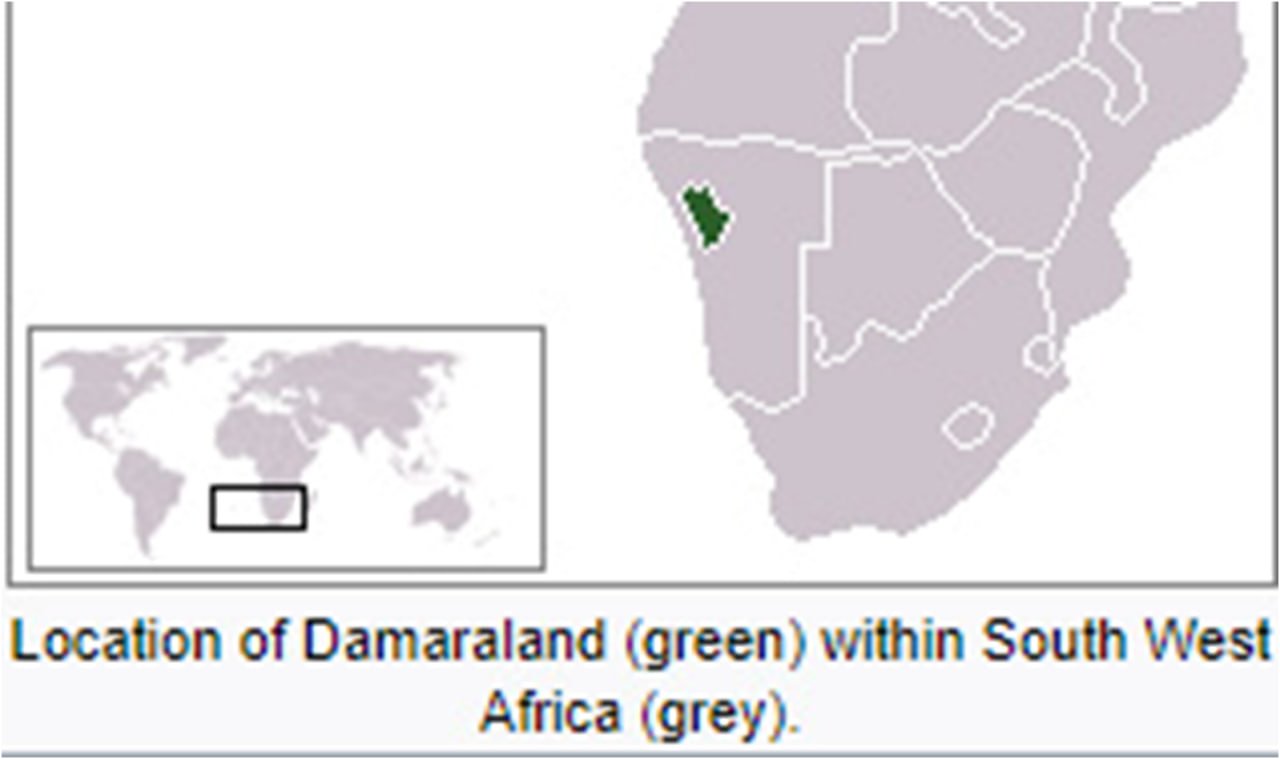

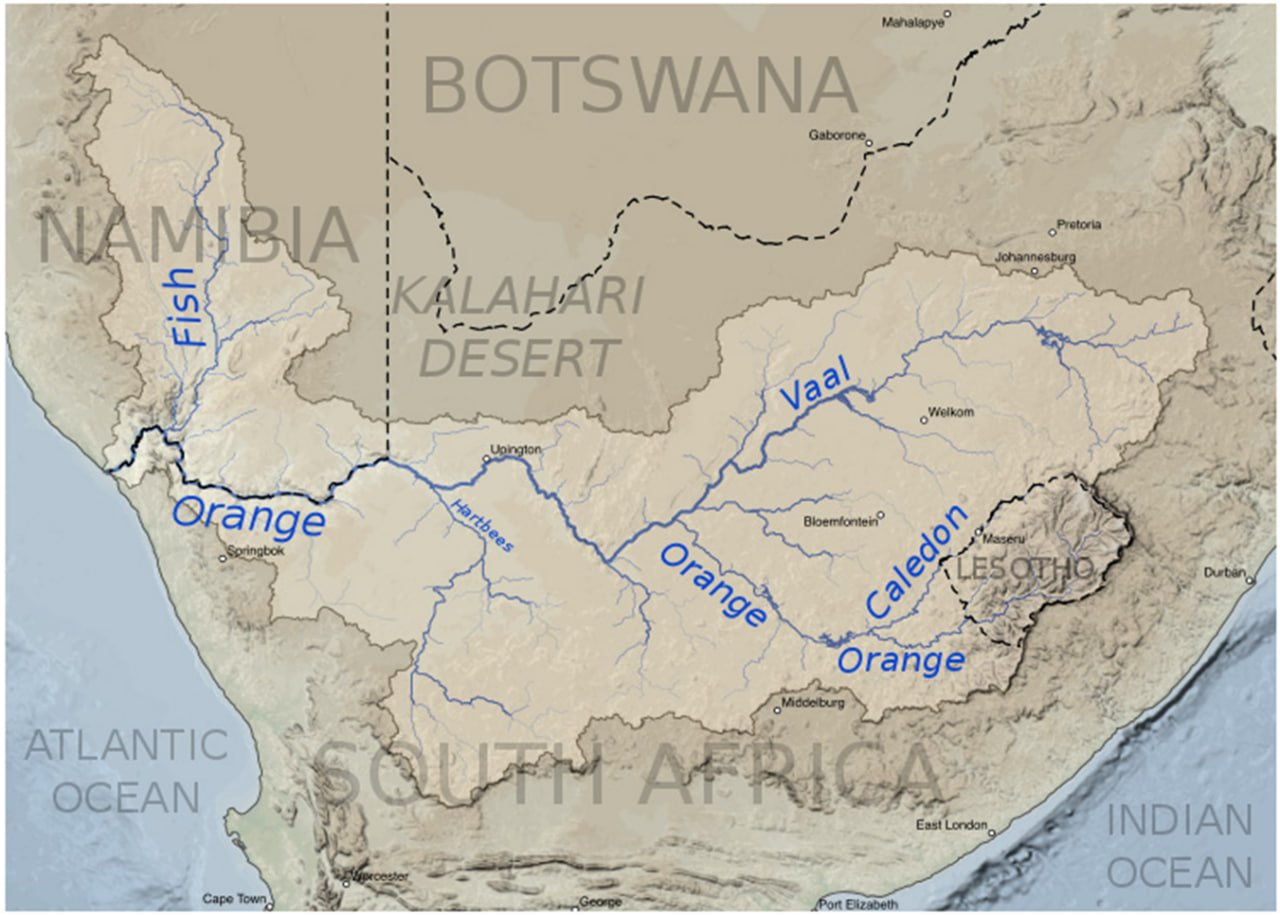

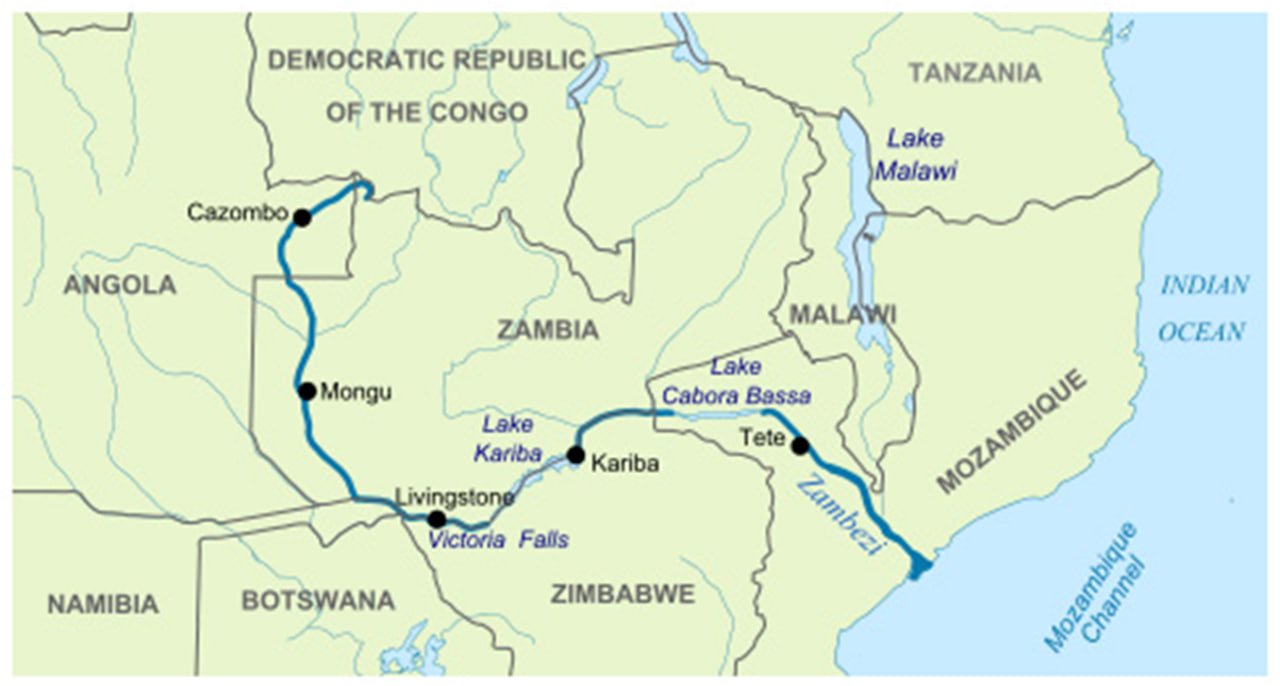

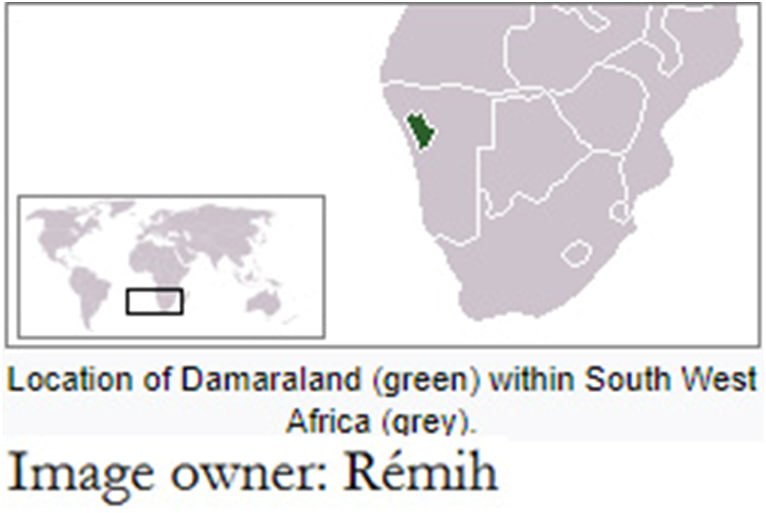

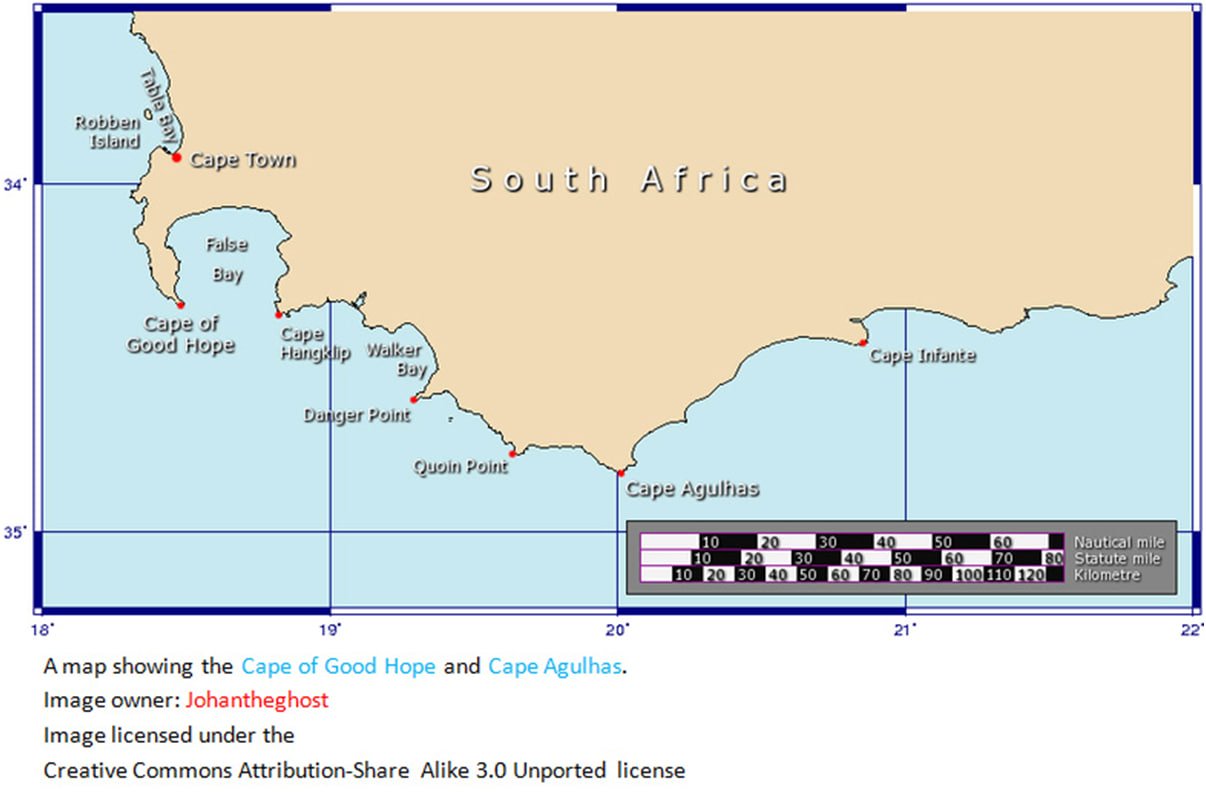

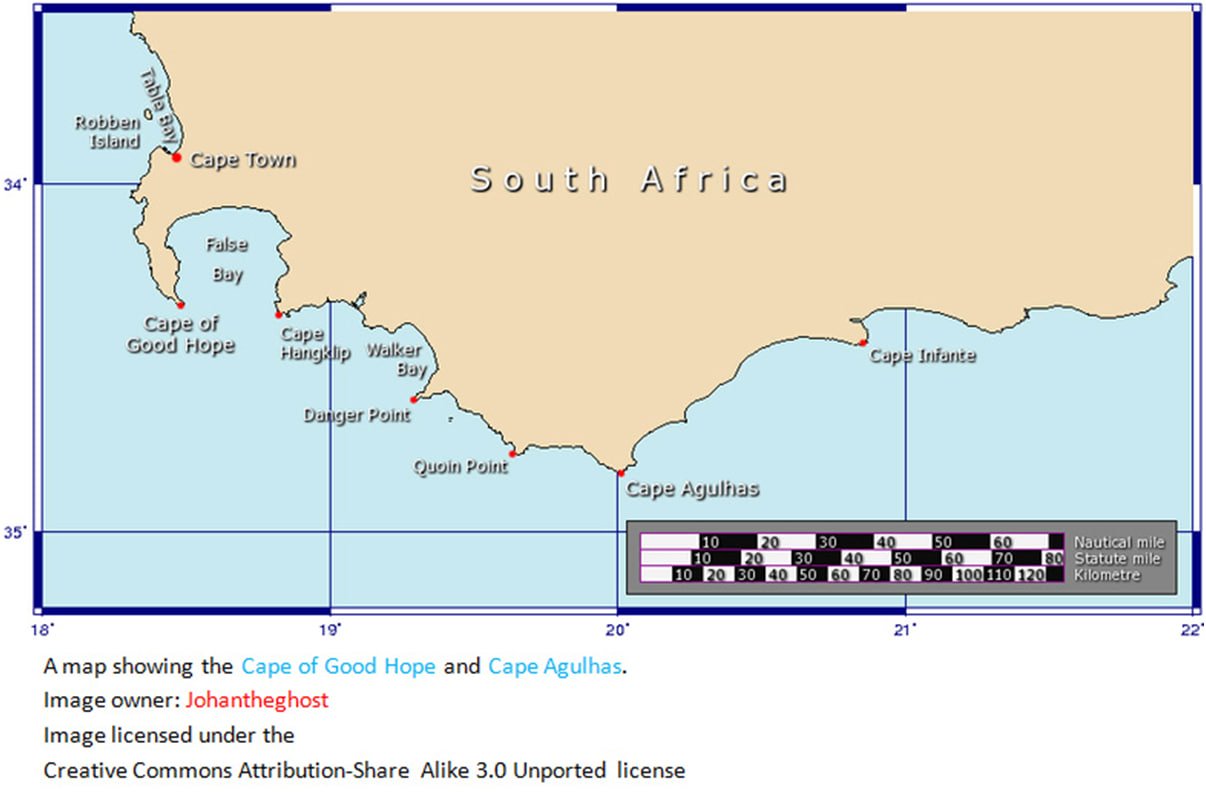

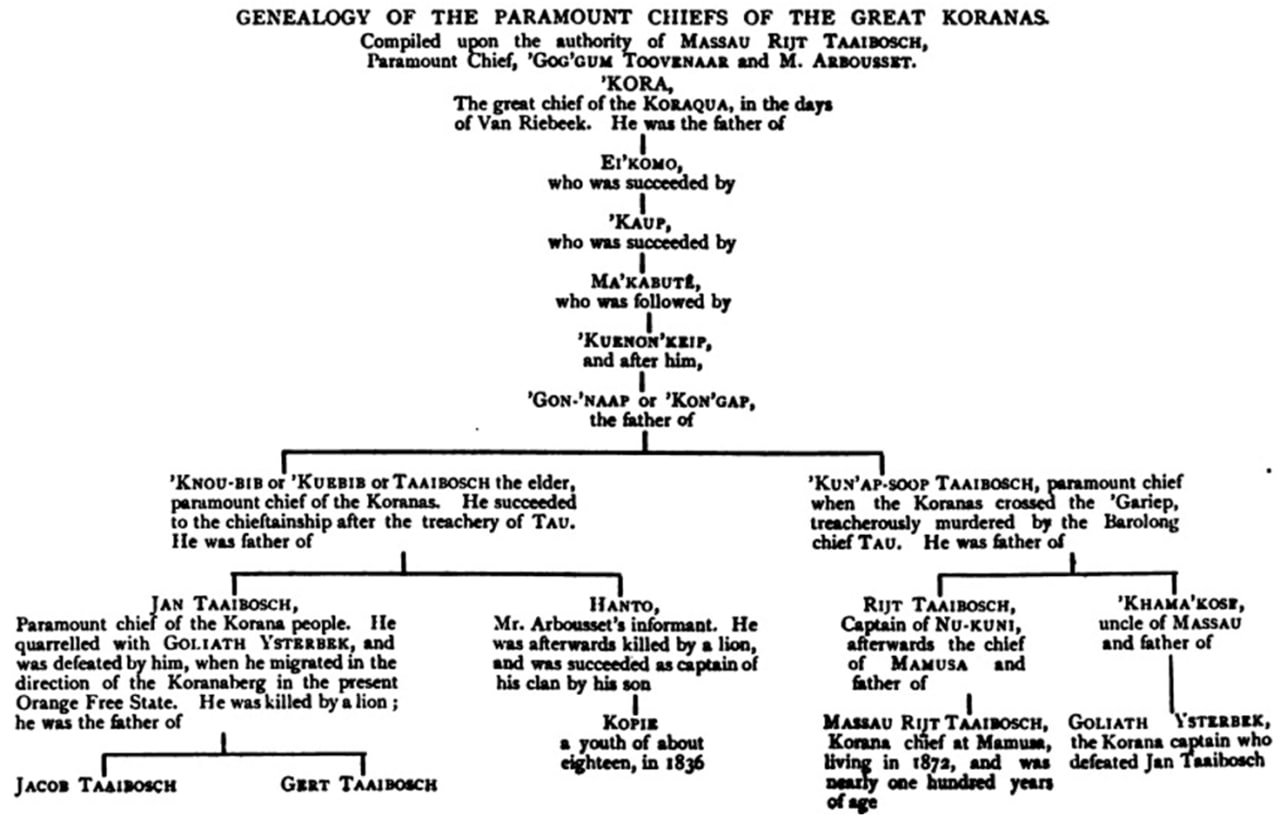

South Africa, the place, is entirely new to me. I have come across a number of population / tribe / races names in this book. See these: The Hottentot tribes, Korana, Bachoana and Basutu tribes, Batlapin, Kaffirs, the Amaxosa, the Abatembu and Amampondo tribes, the Amazulu, Matabli, and Natal tribes, Cochoqua, Chainouqua, Namaqua, Africaander, Berg-Damaras, Ovaherero, Damara, Leghoya, Griqua, Mantatees, Bergenaars, Bakuena &c.

All of them are new to me, and most of them do not connect my mind to any specific imagination of any population. I do not have much clear chronological order in my mind with regard to them.

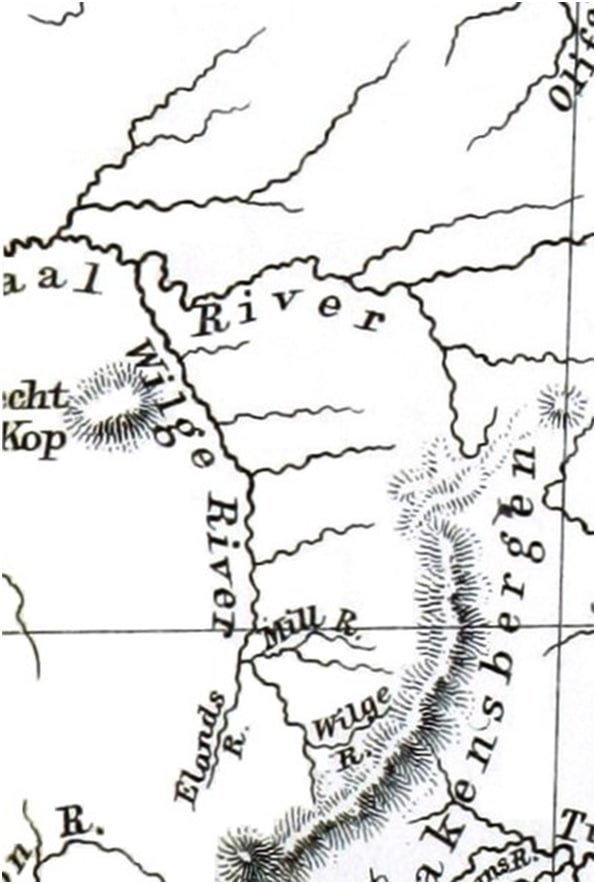

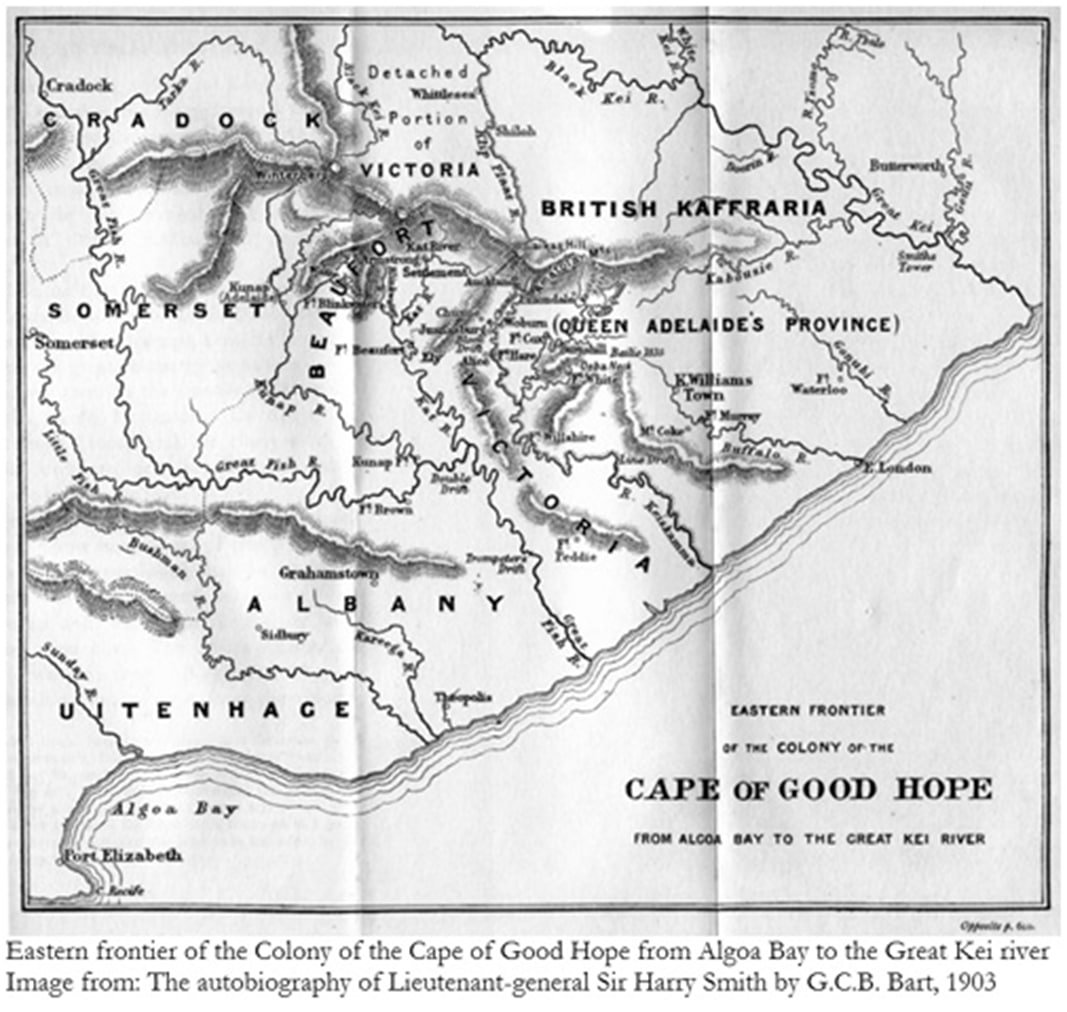

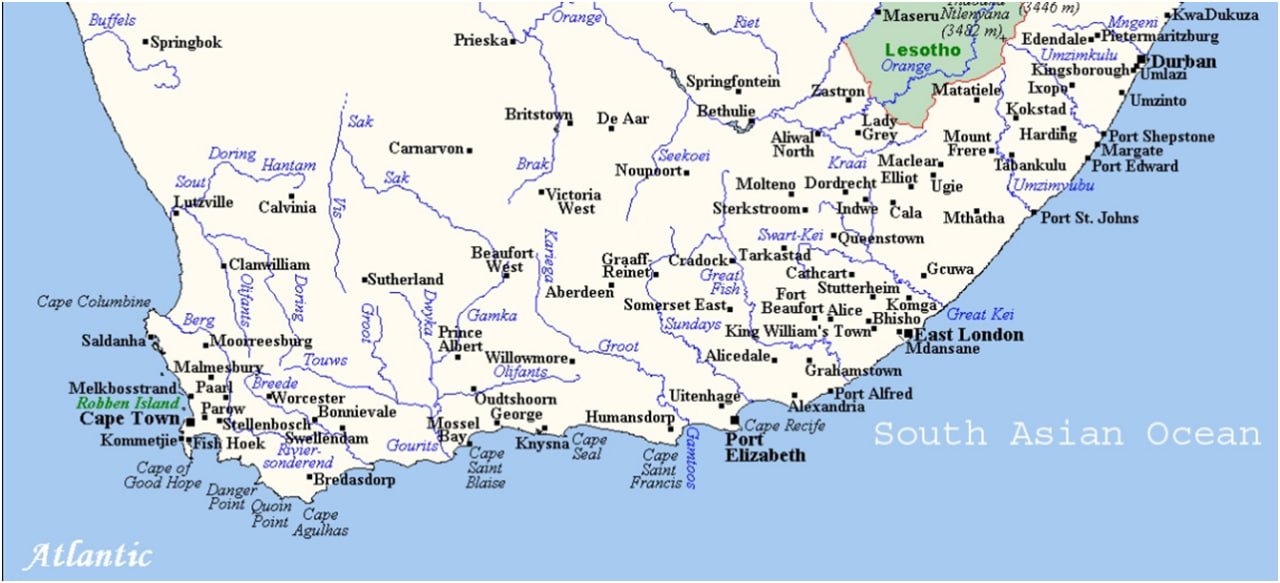

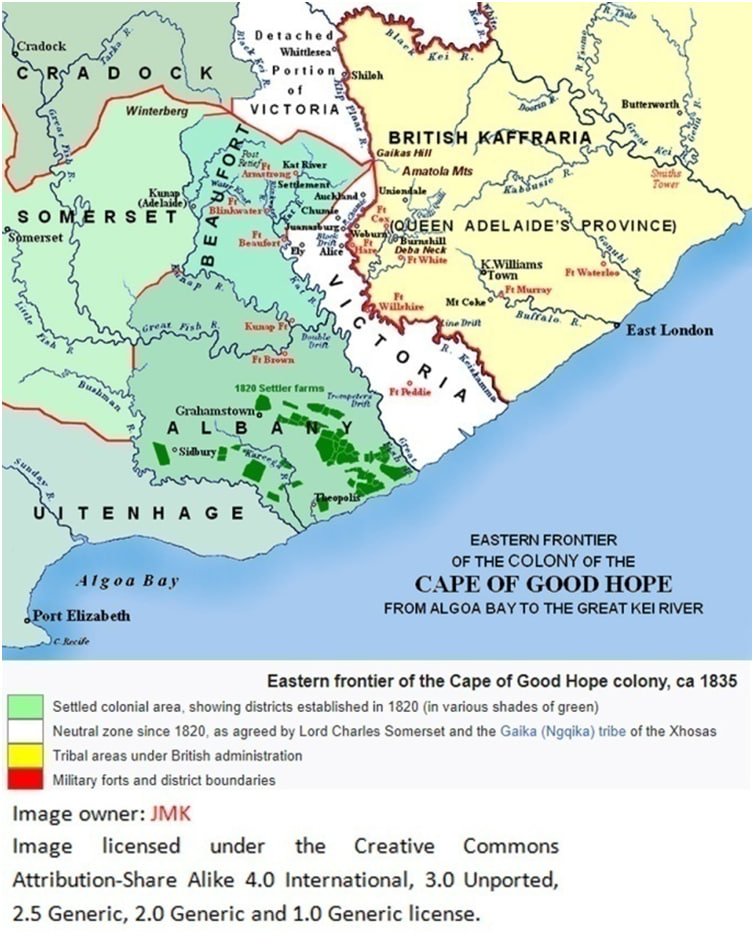

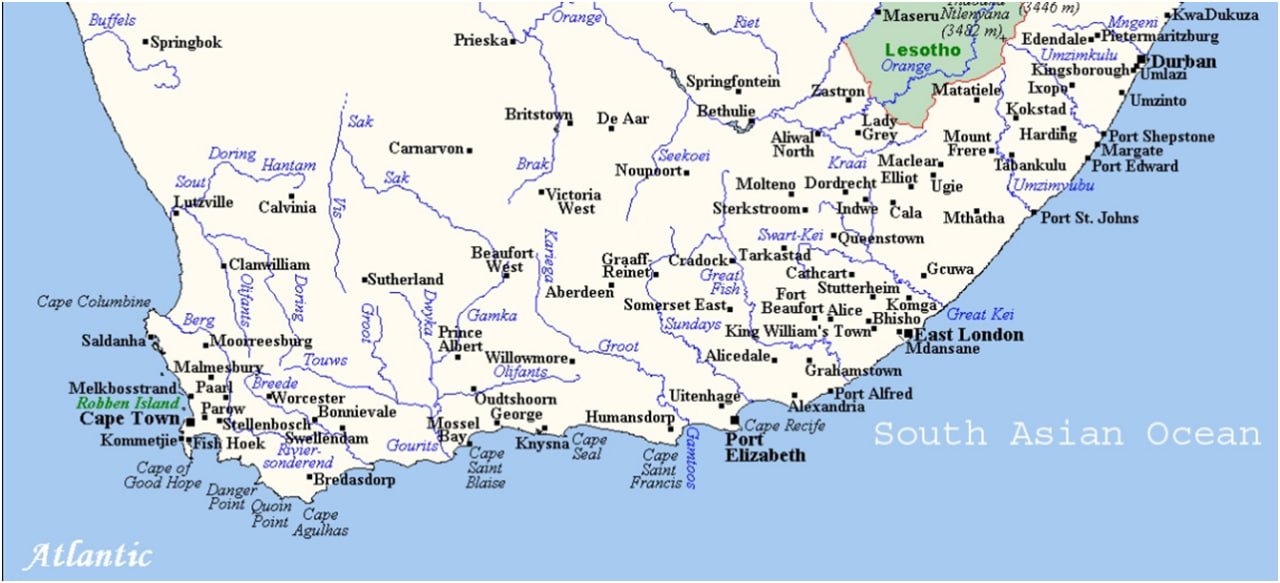

In a similar manner, a lot of new places names have also come into my notice. Almost all are new to me. Without referring to the text in book, I would find it difficult to connect any of the populations to any of the places.

After having confessed that much, I need to think of what the imagination of the whole book creates in my mind. It is a powerful book, no doubt. A lot of sociological and historical events have been recorded or collected in this book. From this perspective, it is a good book.

There is another perspective also that needs to be mentioned. It is that neither this book nor its author has been able to penetrate into the mindset, emotional triggers, cravings, inhibitions, restrictions, strictures, immunities etc. that are encoded in the languages or communication codes of the native tribes or races. This is actually a very vital point fit for elaboration.

It is like this: I am reasonably good in English, have some reading experience in English Classics, have read a number of Enid Blyton books, have lived at times in an English-only social ambience inside South Asia and I can understand the various communication freedoms and mental stature that English can give. I can understand the huge benefits a native-English population would have derived by merely living inside a pristine-English ambience. Moreover, I do have a reasonable amount of understanding of the mood of a native-English individual, commoner or from the nobility. Beyond that I do have some information on how the native-English are different from their own Celtic language countrymen. I do even have some information on the difference that the English have from the Continental Europeans.

I cannot elaborate on these claims of mine here. However, the interested reader can check certain of my other books.

However, I am not a native-Englishman. I am by heredity and ethnicity from current-day South Asia, even though by antiquity I can be connected to some other geographical location. For, many of the South Asian populations are really from various geographical locations in the world, who by some tragic twist of fate had got entrapped in the South Asian social shackles.

When I read books written by the officials of the erstwhile English rule in South Asia, I find them quite profound. Many of the writers have taken a lot of pain to study their subject matter in great detail. Yet, all of the writings and assertions remain very superficial, from my own perspective. This is just because I understand the language codes of the local populations, in their various complexities or lack of it.

This is one defect that all ancient-time studies done by the native-English have. They have no information on the existence of a different human imagination system, quite different from English. The emotions, imaginations, human relationships designed by mere word-codes, the powerful hierarchies that get build up when certain words are used, the loyalties and commitments that get powerfully laid down, the verbal codes that can be used to place terrific hold on certain others, the emotions of worship and hate different form of words with the same meaning can create &c. are totally unknown to the native-English writers. They can only see the effect of the codes or the working of the social machinery. But they have no information on the various verbal codes that creates the actions or the emotions.

Even though I do not want to pursue the feudal language theme here, I can give a minute illustrative example to show what it is all about.

The Indian army as well as the Pakistani army are actually the continuation of the British-Indian army. So, both of them do retain a lot of conventions, procedures, uniforms, parade systems etc. which they had inherited from the erstwhile English army. The senior army officers who are designated as Commissioned Officers (this term itself is connected to the English Monarch) do try to copy and imitate the English army officer class in demeanour, grooming, table manners, sitting postures etc. During the officer training period they are generally mentioned as the Gentlemen Cadets. Some of the senior Indian army officers do don hats and other paraphernalia which might make the common man in India think that they are on the same level as or even superior to an English army officer. In fact, it might seem quite easy to imagine that the senior Indian army officers are more or less of the same mental standards as an English army officer. A few of them might even speak good quality English.

However, there are acute differences between a senior Indian army officer and an English army officer. The major difference is that the Indian officers are at home in Hindi. They address the subordinate ordinary soldiers in Hindi. They address them as the lower slot You in Hindi, that is, Thoo. The ordinary soldier would address them back with an Aap or Saab. This is, the highest level of You. In the Indian army, the Thoo-Aap ladder-step like hierarchy starts from the top Aap level and reaches down to the lowest Thoo level.

Other words like he, his, him, she, her, hers &c. also change into the corresponding form of the selected You. This slotted version of communication would encompass not only the officers and soldiers, but even their family members, relatives, companions &c.

In the English army, this terrific compressing of human self-esteem does not take place in the military hierarchy. So, even when the Indian senior army officers and the English army officers might seem similar, there is actually a total difference in what they are part of and how their mental encoding works.

To illustrate the extreme power of the verbal codes of South Asia, I will give one more illustration, again from the South-Asian armies.

Recently one of India’s Air force pilots was captured by Pakistan. He had been shot down during a bombing mission inside Pakistan. The people who caught him would have bashed him up to death. However, he was saved by the Pakistani military officers. Moreover, he was literally given a royal treatment by the Pakistani military officers. There can be a number of reasons as to why he was saved. Beyond the generally discussed themes, there can even be the possibility that someone in his family had connection with the pan-national arms dealer network, which has connection with the military brass on both sides. They can very easily put in word to the other side to see that the captured person’s skin is saved.

That all is however irrelevant here. What is of relevance here is the verbal codes that was used in all conversations between the Pakistani Military side and the captured person. The conversations were in English. Why?

It is a very pertinent question. For both sides of the fight are at home in Hindi. Yet they preferred to speak in English.

Whatever might be the answer given, the real fact is that English is used to avoid the feudal language encoding issues that would crop up. The Pakistani military would be compelled to use Thoo (lowest You) and the captive person would be under compulsion to use ‘Aap’ (highest You). When this is done, a lot of other verbal codes in Hindi would divide spontaneously into higher and lower attributes. The captured person would sink into the level of a diminutive personality.

In a way, the Pakistani Military officers protected a counterpart of theirs, from a very necessary personality degrading by simply using English. This point has not been appreciated by the Indian side. Even if it was understood, it was not publicly acknowledged. For, such an admission would have brought into the open various hidden issues, including the fact that Hindi is a very carnivorous language.

If the war had continued, these kinds of mutual support by the officer classes would not have continued. Things would have dropped down to the traditional barbarian communication codes. The captured officers on both sides would be addressed and questioned by the lower-placed ordinary soldiers at the Thoo (lowest you) level.

Even a very friendly interaction by the ordinary soldiers with the captive officer from the other side would have been a terribly traumatic experience for the captive officer. For, they, in a pose of extreme friendliness, would have addressed the captive officer by his mere name, Thoo &c. and used the USS (lowest he/him) to refer to him.

The explosive level of personality degradation that would come about from this friendly pose cannot be understood by a native-English person. In fact, when there was the shooting of an engineer from South Asia in the US by a person named Adam Purinton, I did have a conversation with the South Asian side about the verbal code issue. Even though that side was quite abusive and cantankerous, it did ultimately emerge that the dead engineer’s side did use the explosive verbal codes on Adam Purinton. These are things that are quite easily understood in South Asia. And these mental explosions can be very easily demonstrated. That is, the homicidal mania that gets ignited can be demonstrated for any kind of research into this effect. However, the Adam Purinton’s legal defence side had no inkling at all of all these things.

I need to very categorically mention that the native-English, though secluded from very many negative emotional traps and sinister social encodings, are a very foolish and gullible lot in the sense that they are being fooled by the cunning fake affability of the others. They do not have much information on what the world is just beyond the borders of the pristine-English world. They have been led and misled by others on various items to terrific historic traps.

South Africa, the place, is entirely new to me. I have come across a number of population / tribe / races names in this book. See these: The Hottentot tribes, Korana, Bachoana and Basutu tribes, Batlapin, Kaffirs, the Amaxosa, the Abatembu and Amampondo tribes, the Amazulu, Matabli, and Natal tribes, Cochoqua, Chainouqua, Namaqua, Africaander, Berg-Damaras, Ovaherero, Damara, Leghoya, Griqua, Mantatees, Bergenaars, Bakuena &c.

All of them are new to me, and most of them do not connect my mind to any specific imagination of any population. I do not have much clear chronological order in my mind with regard to them.

In a similar manner, a lot of new places names have also come into my notice. Almost all are new to me. Without referring to the text in book, I would find it difficult to connect any of the populations to any of the places.

After having confessed that much, I need to think of what the imagination of the whole book creates in my mind. It is a powerful book, no doubt. A lot of sociological and historical events have been recorded or collected in this book. From this perspective, it is a good book.

There is another perspective also that needs to be mentioned. It is that neither this book nor its author has been able to penetrate into the mindset, emotional triggers, cravings, inhibitions, restrictions, strictures, immunities etc. that are encoded in the languages or communication codes of the native tribes or races. This is actually a very vital point fit for elaboration.

It is like this: I am reasonably good in English, have some reading experience in English Classics, have read a number of Enid Blyton books, have lived at times in an English-only social ambience inside South Asia and I can understand the various communication freedoms and mental stature that English can give. I can understand the huge benefits a native-English population would have derived by merely living inside a pristine-English ambience. Moreover, I do have a reasonable amount of understanding of the mood of a native-English individual, commoner or from the nobility. Beyond that I do have some information on how the native-English are different from their own Celtic language countrymen. I do even have some information on the difference that the English have from the Continental Europeans.

I cannot elaborate on these claims of mine here. However, the interested reader can check certain of my other books.

However, I am not a native-Englishman. I am by heredity and ethnicity from current-day South Asia, even though by antiquity I can be connected to some other geographical location. For, many of the South Asian populations are really from various geographical locations in the world, who by some tragic twist of fate had got entrapped in the South Asian social shackles.

When I read books written by the officials of the erstwhile English rule in South Asia, I find them quite profound. Many of the writers have taken a lot of pain to study their subject matter in great detail. Yet, all of the writings and assertions remain very superficial, from my own perspective. This is just because I understand the language codes of the local populations, in their various complexities or lack of it.

This is one defect that all ancient-time studies done by the native-English have. They have no information on the existence of a different human imagination system, quite different from English. The emotions, imaginations, human relationships designed by mere word-codes, the powerful hierarchies that get build up when certain words are used, the loyalties and commitments that get powerfully laid down, the verbal codes that can be used to place terrific hold on certain others, the emotions of worship and hate different form of words with the same meaning can create &c. are totally unknown to the native-English writers. They can only see the effect of the codes or the working of the social machinery. But they have no information on the various verbal codes that creates the actions or the emotions.

Even though I do not want to pursue the feudal language theme here, I can give a minute illustrative example to show what it is all about.

The Indian army as well as the Pakistani army are actually the continuation of the British-Indian army. So, both of them do retain a lot of conventions, procedures, uniforms, parade systems etc. which they had inherited from the erstwhile English army. The senior army officers who are designated as Commissioned Officers (this term itself is connected to the English Monarch) do try to copy and imitate the English army officer class in demeanour, grooming, table manners, sitting postures etc. During the officer training period they are generally mentioned as the Gentlemen Cadets. Some of the senior Indian army officers do don hats and other paraphernalia which might make the common man in India think that they are on the same level as or even superior to an English army officer. In fact, it might seem quite easy to imagine that the senior Indian army officers are more or less of the same mental standards as an English army officer. A few of them might even speak good quality English.

However, there are acute differences between a senior Indian army officer and an English army officer. The major difference is that the Indian officers are at home in Hindi. They address the subordinate ordinary soldiers in Hindi. They address them as the lower slot You in Hindi, that is, Thoo. The ordinary soldier would address them back with an Aap or Saab. This is, the highest level of You. In the Indian army, the Thoo-Aap ladder-step like hierarchy starts from the top Aap level and reaches down to the lowest Thoo level.

Other words like he, his, him, she, her, hers &c. also change into the corresponding form of the selected You. This slotted version of communication would encompass not only the officers and soldiers, but even their family members, relatives, companions &c.

In the English army, this terrific compressing of human self-esteem does not take place in the military hierarchy. So, even when the Indian senior army officers and the English army officers might seem similar, there is actually a total difference in what they are part of and how their mental encoding works.

To illustrate the extreme power of the verbal codes of South Asia, I will give one more illustration, again from the South-Asian armies.

Recently one of India’s Air force pilots was captured by Pakistan. He had been shot down during a bombing mission inside Pakistan. The people who caught him would have bashed him up to death. However, he was saved by the Pakistani military officers. Moreover, he was literally given a royal treatment by the Pakistani military officers. There can be a number of reasons as to why he was saved. Beyond the generally discussed themes, there can even be the possibility that someone in his family had connection with the pan-national arms dealer network, which has connection with the military brass on both sides. They can very easily put in word to the other side to see that the captured person’s skin is saved.

That all is however irrelevant here. What is of relevance here is the verbal codes that was used in all conversations between the Pakistani Military side and the captured person. The conversations were in English. Why?

It is a very pertinent question. For both sides of the fight are at home in Hindi. Yet they preferred to speak in English.

Whatever might be the answer given, the real fact is that English is used to avoid the feudal language encoding issues that would crop up. The Pakistani military would be compelled to use Thoo (lowest You) and the captive person would be under compulsion to use ‘Aap’ (highest You). When this is done, a lot of other verbal codes in Hindi would divide spontaneously into higher and lower attributes. The captured person would sink into the level of a diminutive personality.

In a way, the Pakistani Military officers protected a counterpart of theirs, from a very necessary personality degrading by simply using English. This point has not been appreciated by the Indian side. Even if it was understood, it was not publicly acknowledged. For, such an admission would have brought into the open various hidden issues, including the fact that Hindi is a very carnivorous language.

If the war had continued, these kinds of mutual support by the officer classes would not have continued. Things would have dropped down to the traditional barbarian communication codes. The captured officers on both sides would be addressed and questioned by the lower-placed ordinary soldiers at the Thoo (lowest you) level.

Even a very friendly interaction by the ordinary soldiers with the captive officer from the other side would have been a terribly traumatic experience for the captive officer. For, they, in a pose of extreme friendliness, would have addressed the captive officer by his mere name, Thoo &c. and used the USS (lowest he/him) to refer to him.

The explosive level of personality degradation that would come about from this friendly pose cannot be understood by a native-English person. In fact, when there was the shooting of an engineer from South Asia in the US by a person named Adam Purinton, I did have a conversation with the South Asian side about the verbal code issue. Even though that side was quite abusive and cantankerous, it did ultimately emerge that the dead engineer’s side did use the explosive verbal codes on Adam Purinton. These are things that are quite easily understood in South Asia. And these mental explosions can be very easily demonstrated. That is, the homicidal mania that gets ignited can be demonstrated for any kind of research into this effect. However, the Adam Purinton’s legal defence side had no inkling at all of all these things.

Last edited by VED on Wed Dec 06, 2023 4:33 pm, edited 1 time in total.

3

c3 #

Lowering of the native-English mental stamina

Lowering of the native-English mental stamina

I mentioned so much to mention that native-English colonial officials and writers never did get to understand the exact content of barbarianism deeply encoded inside the barbarian and semi-barbarian areas which they got to administer and improve.

The modern English citizen in England is not the original native-English citizens of yore. The modern specimen is a corrupted and low grade individual, when compared to the original native-English individuals. This lowliness comes from having achieved a level of equality with the feudal language speaking persons who have barged into England. Many of these persons, who have swarmed in, are mostly the children of corrupt-to-the-core officials of other nations. Others can be the lowly-placed persons’ children. Feudal languages actually give a very satanic power to the lowly placed persons, if they are allowed to grow up and address the social seniors as equals. This danger also, England does not understand.

Equality with the feudal language individuals is an equality with an entity that can oscillate another being between stinking dirt and fragrant gold. Those persons can literally clasp another person and get him attached to the stinking dirt layer of human existence or to the golden layers. These are things that cannot be made understood in English. The easiest way to demonstrate this is to simply show the extreme urge of these individuals to get out of their own nations and to sink their teeth into the vital interiors of native-English nations.

Even a simple question in English as, Where are you going? can be asked using various and varying verbal codes in feudal languages. These shifting or changing of verbal codes can literally swing a person across different social levels, or display various kinds of attachments to other persons. Each of these shifts can powerfully place the person in various kinds of social or positional shackles. Or they can place him in positions of power over others. Each of these positions can very directly affect his own equation with many other individuals including his own subordinates, superiors, wife, children etc. His own position can affect his children, wife, parents and even his superiors and subordinates, in their own spheres of activity and socialising.

All these terrific information get hidden in English. And this is the great tragedy that is entering into native-English nations, when multiculture is being given the go-ahead. No one over there seems to understand that they have no information on the exact amplitude and ambit of the term ‘multiculture’. Or why exactly all these multiculture individuals are running out of their own cultural lands, and would go suicidal or homicidal if forced to relocate back to their homeland.

The modern English citizen in England is not the original native-English citizens of yore. The modern specimen is a corrupted and low grade individual, when compared to the original native-English individuals. This lowliness comes from having achieved a level of equality with the feudal language speaking persons who have barged into England. Many of these persons, who have swarmed in, are mostly the children of corrupt-to-the-core officials of other nations. Others can be the lowly-placed persons’ children. Feudal languages actually give a very satanic power to the lowly placed persons, if they are allowed to grow up and address the social seniors as equals. This danger also, England does not understand.

Equality with the feudal language individuals is an equality with an entity that can oscillate another being between stinking dirt and fragrant gold. Those persons can literally clasp another person and get him attached to the stinking dirt layer of human existence or to the golden layers. These are things that cannot be made understood in English. The easiest way to demonstrate this is to simply show the extreme urge of these individuals to get out of their own nations and to sink their teeth into the vital interiors of native-English nations.

Even a simple question in English as, Where are you going? can be asked using various and varying verbal codes in feudal languages. These shifting or changing of verbal codes can literally swing a person across different social levels, or display various kinds of attachments to other persons. Each of these shifts can powerfully place the person in various kinds of social or positional shackles. Or they can place him in positions of power over others. Each of these positions can very directly affect his own equation with many other individuals including his own subordinates, superiors, wife, children etc. His own position can affect his children, wife, parents and even his superiors and subordinates, in their own spheres of activity and socialising.

All these terrific information get hidden in English. And this is the great tragedy that is entering into native-English nations, when multiculture is being given the go-ahead. No one over there seems to understand that they have no information on the exact amplitude and ambit of the term ‘multiculture’. Or why exactly all these multiculture individuals are running out of their own cultural lands, and would go suicidal or homicidal if forced to relocate back to their homeland.

Last edited by VED on Wed Dec 06, 2023 4:35 pm, edited 1 time in total.

4

c4 #

What has been missed

What has been missed

This book, THE NATIVE RACES OF SOUTH AFRICA written by GEORGE W. STOW, F.G.S., F.R.G.S. does suffer from this defect. That is, the writer of this book has written this book containing a huge content of details. However, everything does sort of skim over the surface. The hidden codes and their machine-work have been totally missed. Or rather, there is not even a thought that such hidden things, non-tangible to a native-English mind, would be there in existence.

A population group is studied. Their strange or bizarre actions or social conventions are detailed. However, there is no information on why the persons behave in such a strange manner. This is an insight that I did have when I was reading the books written by the officials of the erstwhile English East India Company or by the British officials of British-India. They detail the social system, conventions, inhibitions, strictures, repulsions &c. Beyond that they have no more information of the social machinery. However, when I read them, in many cases, I can very easily visualise the verbal codes that acted upon the persons to create the social effect.

That much is the defect. However, as mentioned earlier, it is not a rare defect in native-English writers.

Speaking about what the book contains, it may be admitted that it does contain a lot of information, for a person who knows what to look for. This again is a very profound statement. It is like a native-Englishman coming to South Asia and finding everyone quite friendly, welcoming and affectionate. However, if the person knows something about the sinister sides of feudal languages, then he or she can know what to look for. A very friendly and affable outward demeanour is a powerful way to trap or allure a wary or unwary antagonist or someone they want to subdue. In feudal languages, there are actually two extremely opposite poses possible.

In this book, one or two such incidences have been mentioned wherein these kinds of mentalities are exhibited.

It may be mentioned here that the native-English colonial behaviour was exemplary and totally opposite to that of the Continental Europeans. However that cannot be expected anymore, because the native-English are now in close contact with the feudal language speakers and many of them are being taught by feudal language teachers. I hope to write about this later in this book. However, interested persons can read my book: The tragic consequences of teaching Hindi in Australia!

A population group is studied. Their strange or bizarre actions or social conventions are detailed. However, there is no information on why the persons behave in such a strange manner. This is an insight that I did have when I was reading the books written by the officials of the erstwhile English East India Company or by the British officials of British-India. They detail the social system, conventions, inhibitions, strictures, repulsions &c. Beyond that they have no more information of the social machinery. However, when I read them, in many cases, I can very easily visualise the verbal codes that acted upon the persons to create the social effect.

That much is the defect. However, as mentioned earlier, it is not a rare defect in native-English writers.

Speaking about what the book contains, it may be admitted that it does contain a lot of information, for a person who knows what to look for. This again is a very profound statement. It is like a native-Englishman coming to South Asia and finding everyone quite friendly, welcoming and affectionate. However, if the person knows something about the sinister sides of feudal languages, then he or she can know what to look for. A very friendly and affable outward demeanour is a powerful way to trap or allure a wary or unwary antagonist or someone they want to subdue. In feudal languages, there are actually two extremely opposite poses possible.

In this book, one or two such incidences have been mentioned wherein these kinds of mentalities are exhibited.

It may be mentioned here that the native-English colonial behaviour was exemplary and totally opposite to that of the Continental Europeans. However that cannot be expected anymore, because the native-English are now in close contact with the feudal language speakers and many of them are being taught by feudal language teachers. I hope to write about this later in this book. However, interested persons can read my book: The tragic consequences of teaching Hindi in Australia!

Last edited by VED on Wed Dec 06, 2023 4:35 pm, edited 2 times in total.

5

c5 #

A most terrific observation

A most terrific observation

There are a number of observations that I have made from the contents of this book. I need to go through them in a systematic manner, as much as possible.

The most terrific observation is that human beings are actually another kind of animals. And also that human beings might not actually be one single kind of animals, but a variety of animals, who anatomically might seem quite close to each other. The wider point for elaboration might be that most of the peoples of the world currently seem to be alike only due to the influence of English.

If there was no English, then it is quite possible that many human races would find it quite difficult to arrive at a similarity in thoughts and conventions, that might give a feel that they are all actually of the same type of living beings. This is a very tall claim and the reader might not be quite amused by this. However, I do not intend to pursue this line of thoughts here. If after reading the full commentary, the reader gets to acknowledge the veracity of this claim, well and good. Otherwise also, it does not matter. May be I should mention that animals also have many thoughts and emotions quite similar to that of mankind.

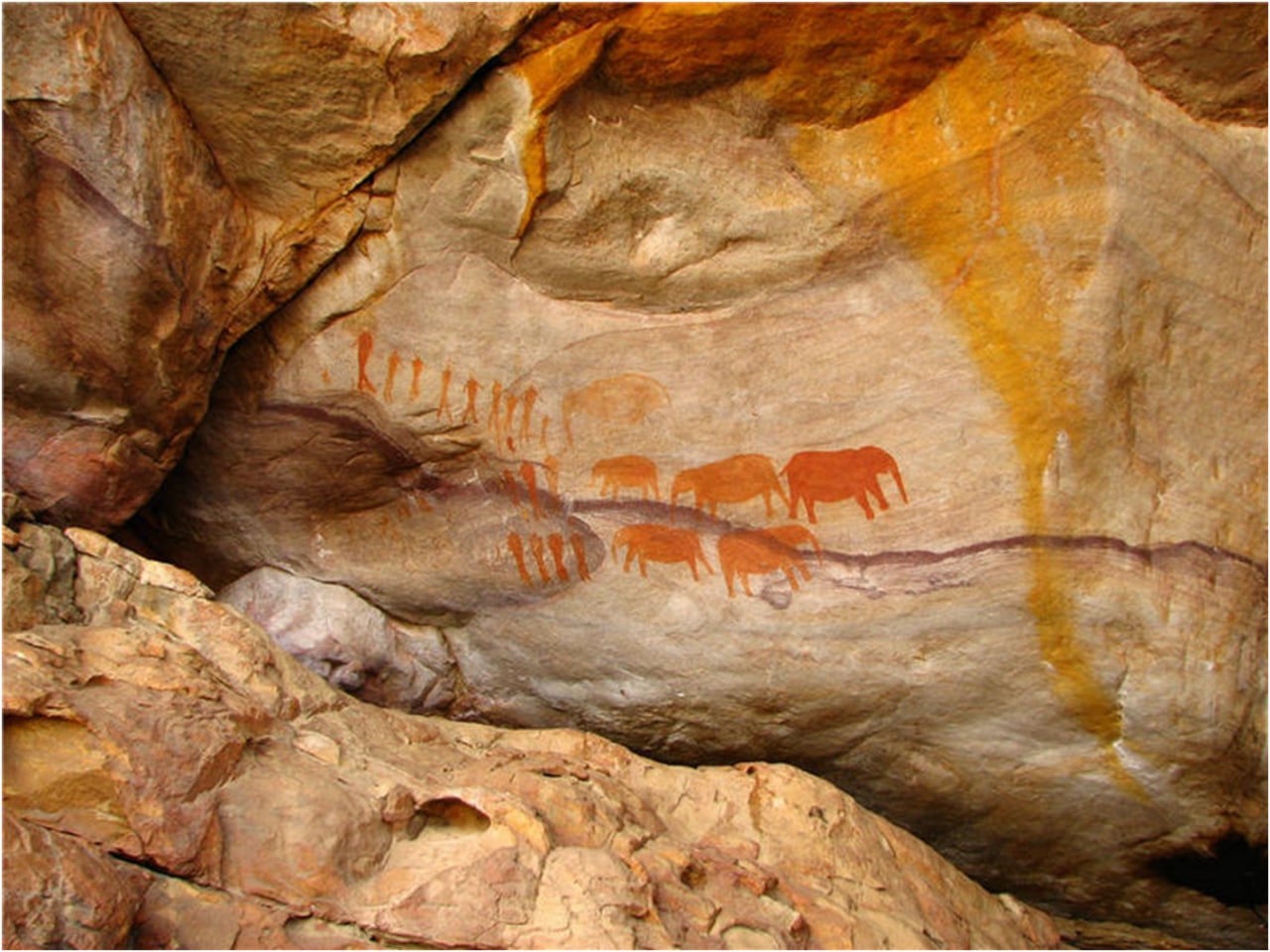

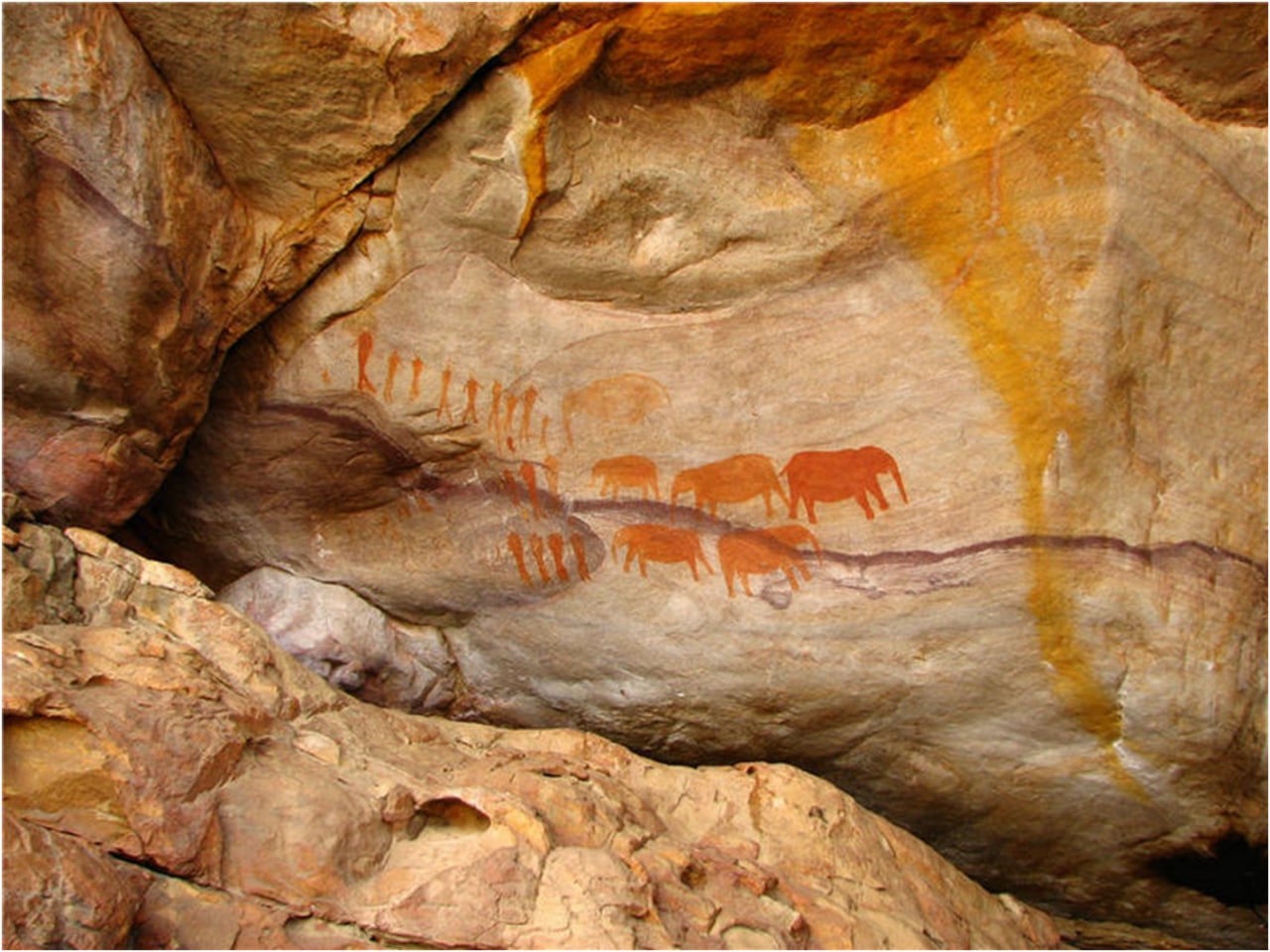

I need to commence from the Bushmen. Actually when I read about them, I did find that they had an attribute which I had mentioned in my earlier writing in my book ‘Shrouded Satanism in feudal languages’. It about what would come about when human beings speak animal languages. Since most the animals do not seem to have a verbal communication as understood as with audible sounds, it is simply that they communicate with each other using other physical and mental features they have or might have.

If human beings can develop the physical capabilities of dogs, carnivorous animals, snakes, fishes etc. what would be the change seen in them? Would they have superior attributes? Well, it is possible that in such an eventuality, the individual might seem to possess animal features. And when this is combined with human capacities of speech, writing, computer & Smartphone use, vehicle driving, speaking standing on a podium, videography etc., the individual would indeed be quite a superior individual or a superman.

However, the exact issue is that the individual will have animal features. If these features are of a living being that is considered to be dangerous, then that individual can very well be seen as a dangerous being.

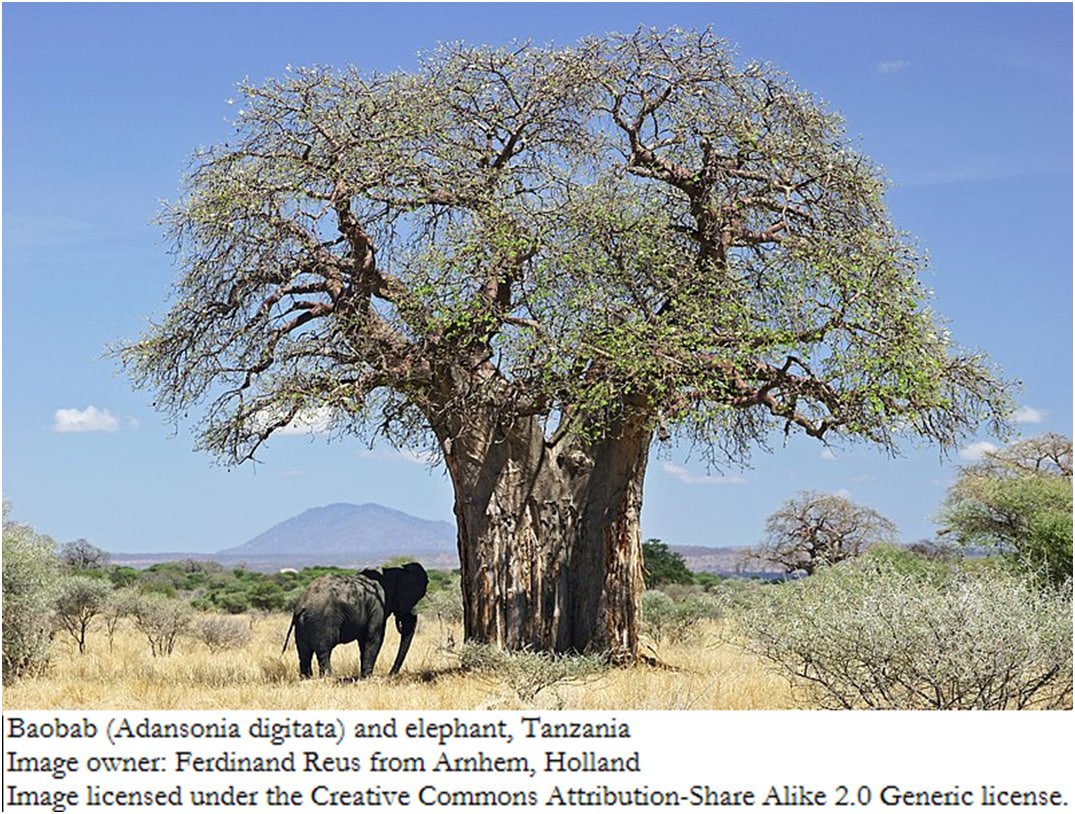

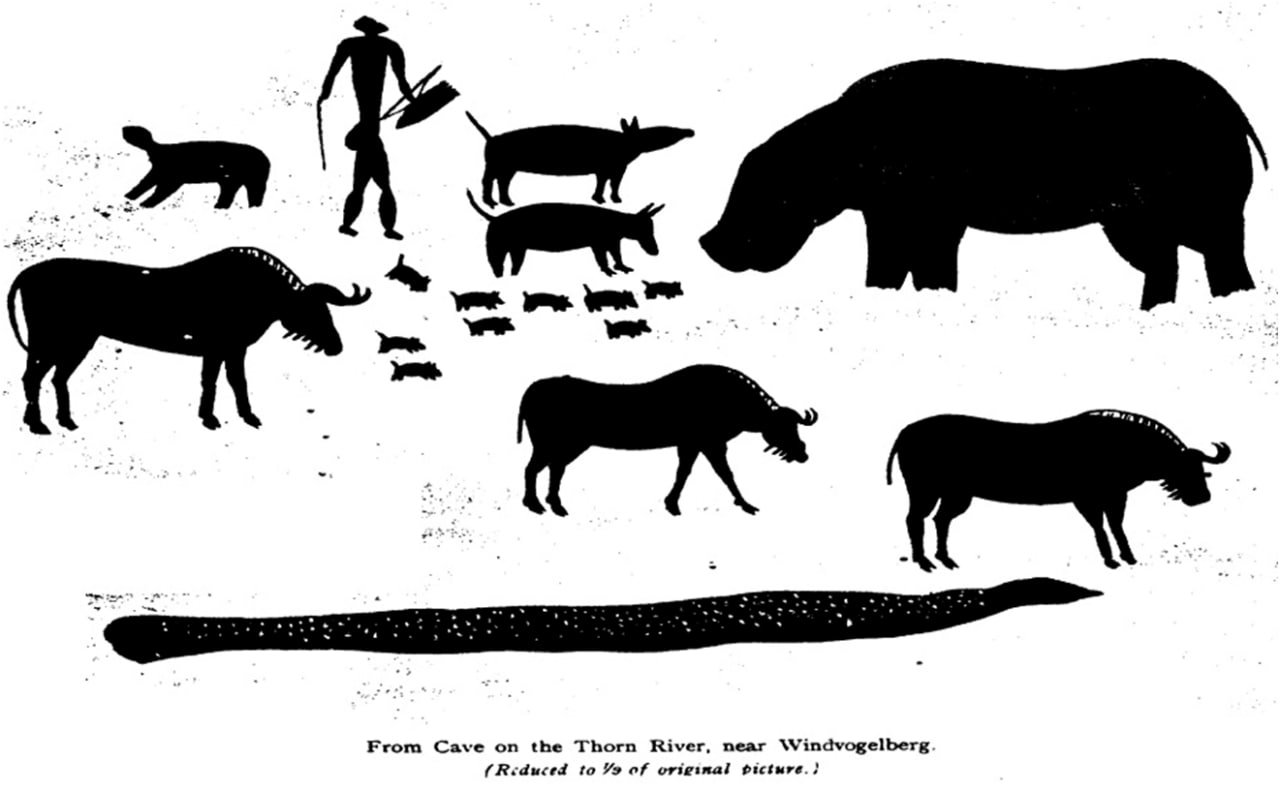

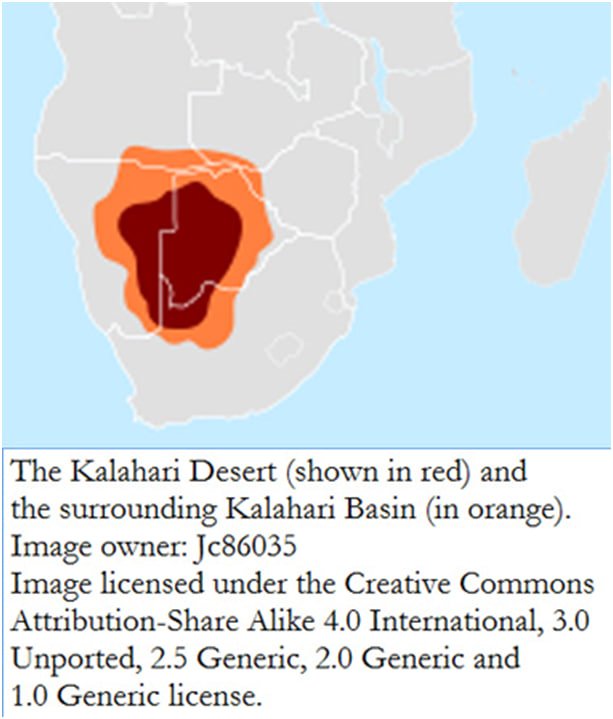

This might be the exact situation in which the Bushmen might have arrived or lived in. They literally had capabilities which were way beyond that of an ordinary human being. However, they lived in the wild in close proximity with the wild animals. In the various locations of areas which later became South Africa, and beyond, they occupied the place in a manner in which their presence was not detected or acknowledged by the human being populations that entered the location or occupied it.

QUOTE 1:

QUOTE 2:

QUOTE 3:

QUOTE 4:

QUOTE 5:

The above statement has a limited bit of merit. However, it cannot go beyond that. For, if the living being who has been living in the natural ambience as much as a wild animal can acquire a great expertise and information on Nature and such things, well then, animals would be great Naturalists.

Actually what could create an individual with super information across the living being fences is a combination of certain very specific attributes. I cannot divulge more about this here.

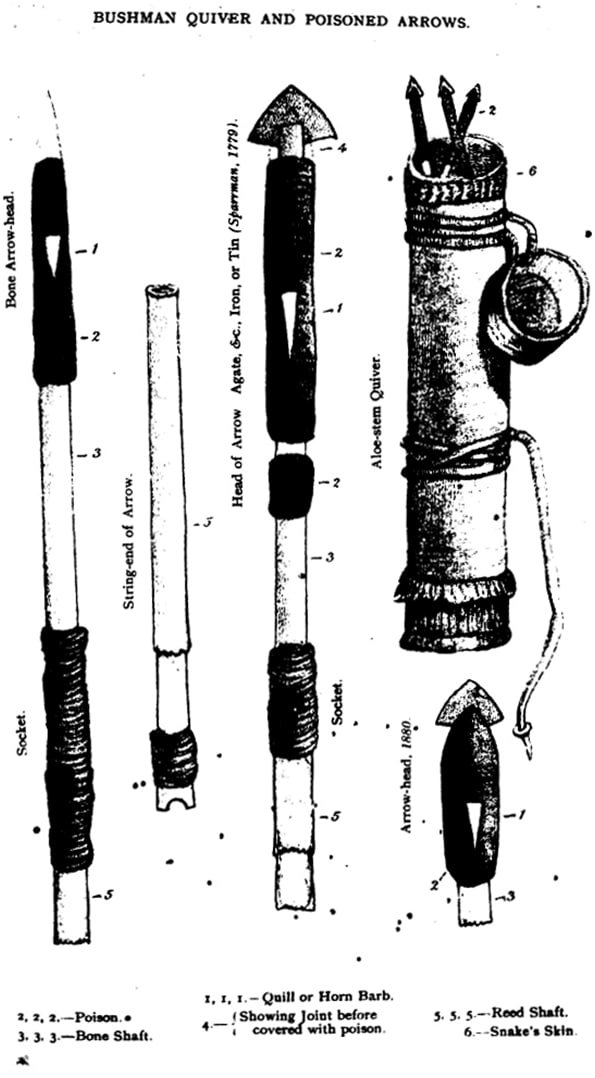

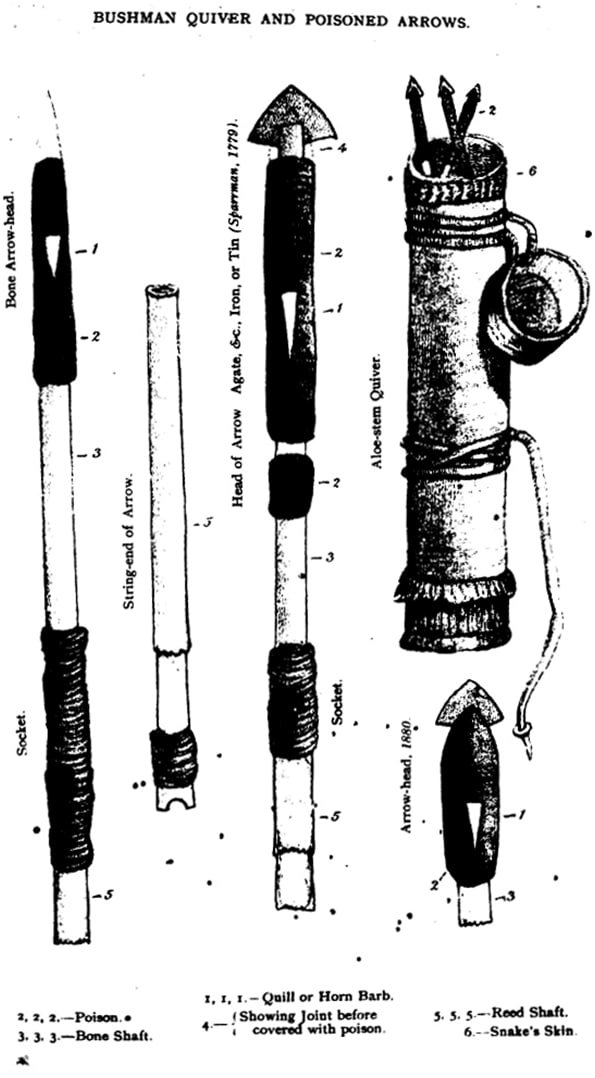

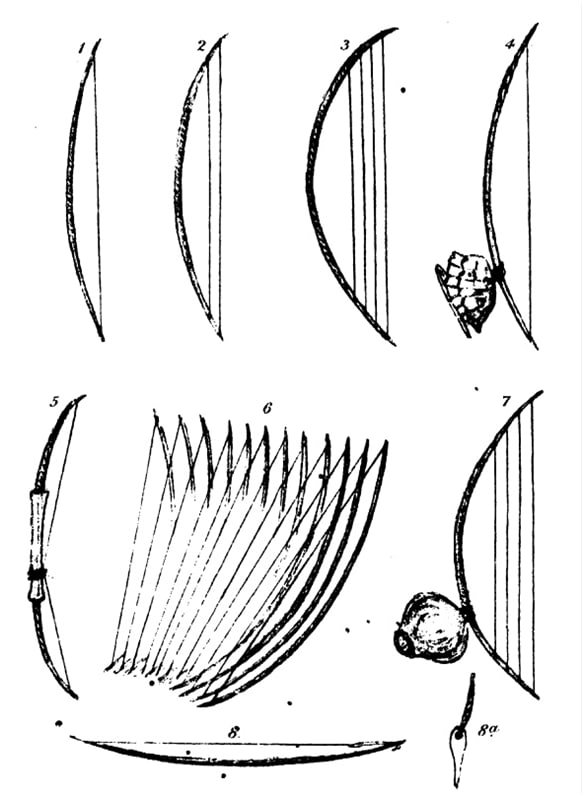

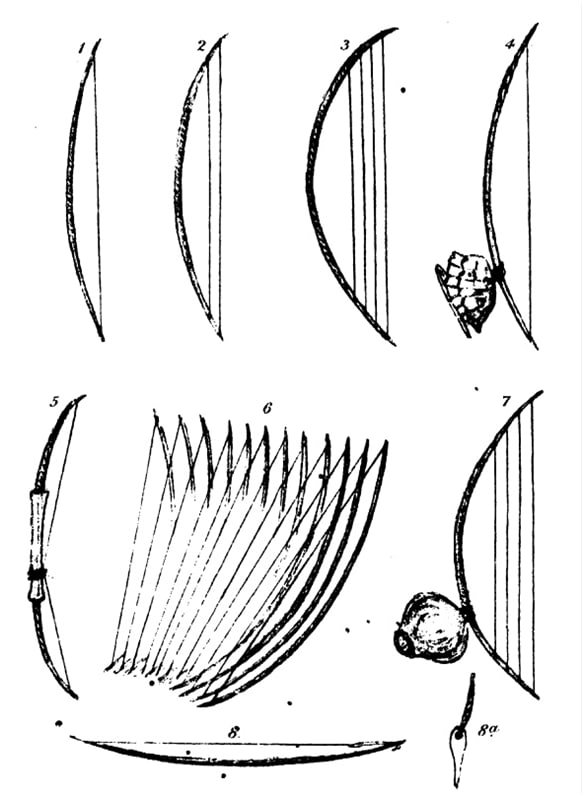

It is seen mentioned all along the writing that the Bushmen were not seen as human beings, but some kind of semi-humans. One of their special features that led to their total destruction was their unique capability to create poisoned arrows. Even though this was a very wonderful item of defence and offence for them, it more or less got them identified with the poisonous beings that live in the borrows.

Even if the arrow they send did not make much of a physical damage in a person, the poison would work and the person would die. This was so terrific an experience that they became a terror. However, the fact that they were initially not at all with any kind of hostile aims can be understood by the way they treated the others who came to occupy their traditional lands. Even the term ‘their traditional lands’ becomes an issue. For, it was like saying that the land traditionally belonged to the poisonous beings in the locality.

The above might be a very clear illustration of the fact that animals are also individuals. It is only a matter of being able to communicate with them. Bushmen could comprehend a bit of the bird communication towards them. Even though they might have had the capability to decode or understand the communication between or among the birds.

QUOTE 1:

QUOTE 2:

The above words are quite evocative of the fact that they were very close to the animals, in that they could sort of read or sense their intentions, track them, sort of communicative with some of them, and could even live in some kind of symbiotic relationship with a few of them. In fact, they were human beings who had the capability to exist as a sort of link between the animal world and that of the human world. After all, animals are apart from human beings only because of the communication problem. In fact, even in South Asia, many human populations had been treated or defined or considered as half animal or semi-human.

These were the lower caste populations such as the Pulaya, Pariah and such others. However, with the advent of the English rule in the subcontinent, all of them were liberated from their semi-human state. However, it was an act for which the higher castes of the location still cannot forgive the English. In fact, there is one rascal member of these higher caste populations who has made a mark on the national psyche by demanding that Britain should pay adequate compensation for what it had done in the Subcontinent.

If the English rule had taken the effort to bring in communication ability in some of the shackled animals of the subcontinent, such as the elephant etc. they too would have entered into close proximity with the human races.

One cannot say if these kinds of talk are insane talk. For, it is possible that some thousands of years back the ancestors of the Bushmen might have had better living standards. How they came to be entrapped in a forest region, and all such things would have very complicated history. The state of the animals also might have been different in a social system where in technical skills were different. In fact, in days to come when software technology improves to such a level that it is possible to communicate with many kinds of animals, those animal stature will change. Many may even enter into the capability of using sophisticated gadgetry.

The most terrific observation is that human beings are actually another kind of animals. And also that human beings might not actually be one single kind of animals, but a variety of animals, who anatomically might seem quite close to each other. The wider point for elaboration might be that most of the peoples of the world currently seem to be alike only due to the influence of English.

If there was no English, then it is quite possible that many human races would find it quite difficult to arrive at a similarity in thoughts and conventions, that might give a feel that they are all actually of the same type of living beings. This is a very tall claim and the reader might not be quite amused by this. However, I do not intend to pursue this line of thoughts here. If after reading the full commentary, the reader gets to acknowledge the veracity of this claim, well and good. Otherwise also, it does not matter. May be I should mention that animals also have many thoughts and emotions quite similar to that of mankind.

I need to commence from the Bushmen. Actually when I read about them, I did find that they had an attribute which I had mentioned in my earlier writing in my book ‘Shrouded Satanism in feudal languages’. It about what would come about when human beings speak animal languages. Since most the animals do not seem to have a verbal communication as understood as with audible sounds, it is simply that they communicate with each other using other physical and mental features they have or might have.

If human beings can develop the physical capabilities of dogs, carnivorous animals, snakes, fishes etc. what would be the change seen in them? Would they have superior attributes? Well, it is possible that in such an eventuality, the individual might seem to possess animal features. And when this is combined with human capacities of speech, writing, computer & Smartphone use, vehicle driving, speaking standing on a podium, videography etc., the individual would indeed be quite a superior individual or a superman.

However, the exact issue is that the individual will have animal features. If these features are of a living being that is considered to be dangerous, then that individual can very well be seen as a dangerous being.

This might be the exact situation in which the Bushmen might have arrived or lived in. They literally had capabilities which were way beyond that of an ordinary human being. However, they lived in the wild in close proximity with the wild animals. In the various locations of areas which later became South Africa, and beyond, they occupied the place in a manner in which their presence was not detected or acknowledged by the human being populations that entered the location or occupied it.

QUOTE 1:

The Hottentots and Bushmen had two remarkable faculties in common : that of quickness of sight and power of endurance in withstanding the cravings of hunger. It was remarked that they could distinguish objects scarcely visible to other men. This faculty was well illustrated in their expertness in watching the flight of bees through the air, and by this means discovering their nest, although at a considerable distance ; the certainty also with which they followed the spoor or trail of animals through a difficult tract of country was another illustration of the same fact, they being frequently able to follow the pursuit at a full run, tiring out horse and rider who accompanied them.

QUOTE 2:

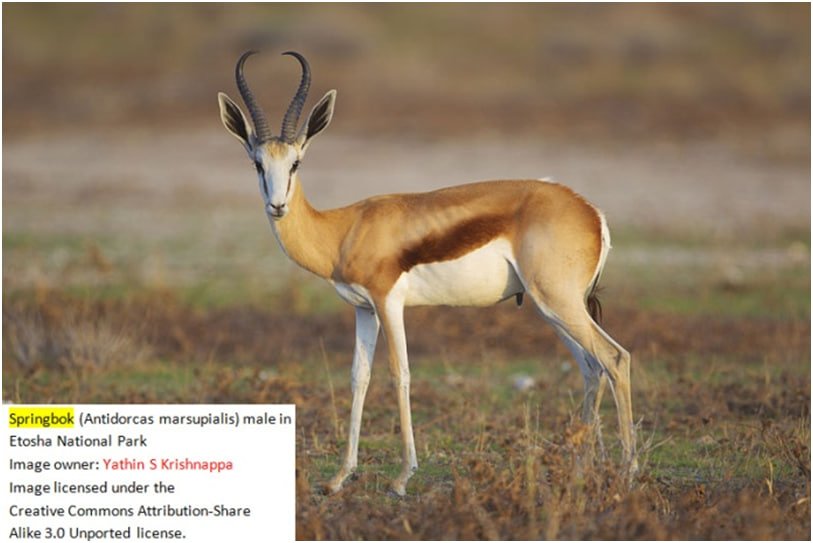

Other tribal traditions, again, state that when their forefathers migrated to the south, they found the land without inhabitants, and that only the wild game and the Bushmen were living in it, evidently classing the Bushmen and the game in the same category as wild animals.

QUOTE 3:

In such a country, and endowed with the activity which it is known they possessed, it is not at all likely that the Bushmen would be the starving miserable people which some have delighted to depict them, before the stronger races invaded their hunting-grounds. Their powers of vision were extraordinary. They were able not only to descry, but to describe, objects at a distance, which were almost invisible to Europeans except with the aid of a telescope.

QUOTE 4:

The country was then stated to be uninhabited, that is, merely in the occupation of wild game and tribes of the Bushman race, whose sole means of subsistence was the chase. Hence their presence was always ignored, although there is overwhelming evidence that the country was then, and for a long period afterwards, thickly populated by them.

QUOTE 5:

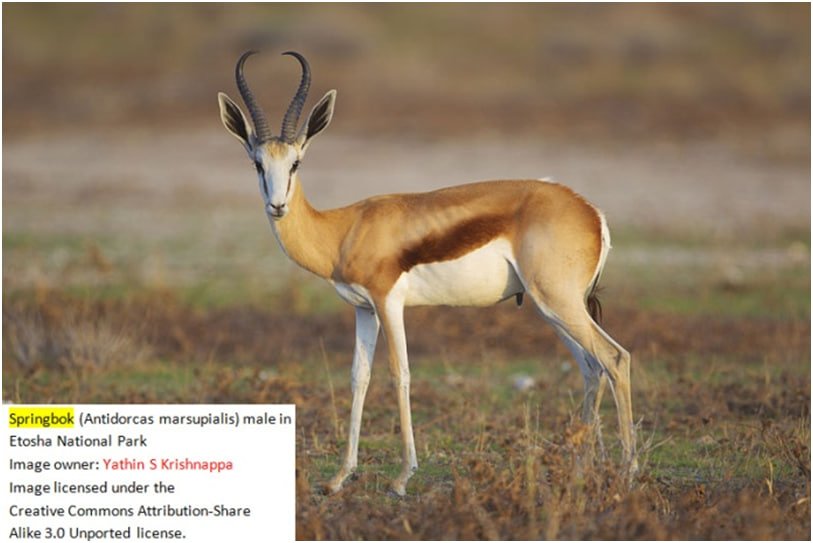

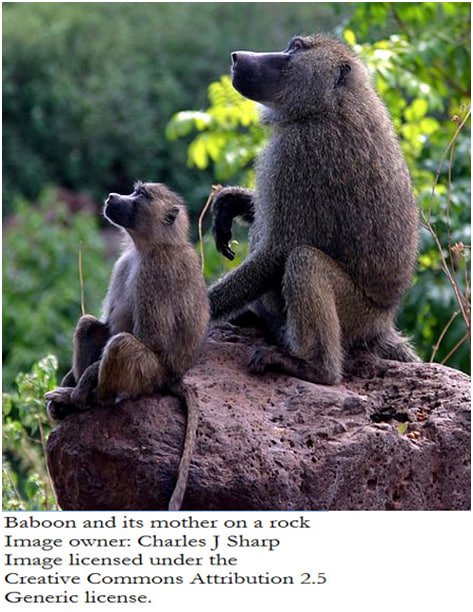

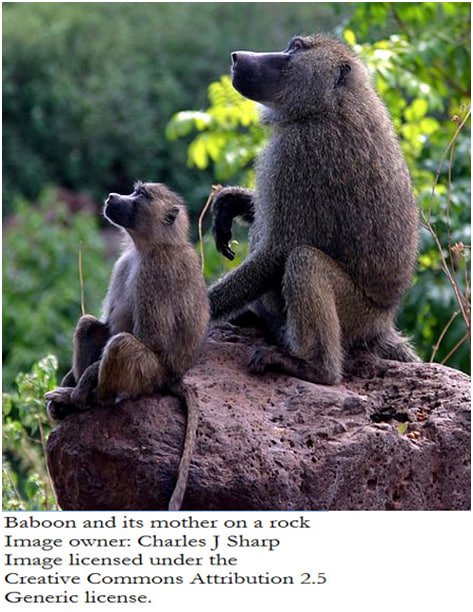

They run like a horse, and in broken rocky ground no horse has a chance of overtaking them. They bound along, and when once among the rocks are like the klipspringers or baboons ; they spring from rock to rock without fear of falling.

He believes that to become an expert naturalist one ought to turn Bushman and conquer the language, when one would learn more about the natural history of many things than from books and years of study and experiment.

The above statement has a limited bit of merit. However, it cannot go beyond that. For, if the living being who has been living in the natural ambience as much as a wild animal can acquire a great expertise and information on Nature and such things, well then, animals would be great Naturalists.

Actually what could create an individual with super information across the living being fences is a combination of certain very specific attributes. I cannot divulge more about this here.

It is seen mentioned all along the writing that the Bushmen were not seen as human beings, but some kind of semi-humans. One of their special features that led to their total destruction was their unique capability to create poisoned arrows. Even though this was a very wonderful item of defence and offence for them, it more or less got them identified with the poisonous beings that live in the borrows.

Even if the arrow they send did not make much of a physical damage in a person, the poison would work and the person would die. This was so terrific an experience that they became a terror. However, the fact that they were initially not at all with any kind of hostile aims can be understood by the way they treated the others who came to occupy their traditional lands. Even the term ‘their traditional lands’ becomes an issue. For, it was like saying that the land traditionally belonged to the poisonous beings in the locality.

They had also a most useful ally and assistant in carrying out this work in the honey-bird — the " Bee-cuckoo " — (Cuculus indicator), of Sparrman, and called " honing wijzer," the honey- guide, by the Hottentots and Dutch. As soon as a Bushman heard its well-known and alluring cry of " cherr, cherr, cherr," he was immediately on the alert, as he knew by experience that the bird was desirous of attracting attention. Finding that it had been successful in doing this, it flew a short distance in front, repeating the cry.

As the Bushman followed, it again went a little farther, slowly and by degrees towards the quarter where the swarm of bees had taken up their abode, all the while repeating its cry of " cherr, cherr." The Bushman answered it now and then with a low gentle whistle, to let the bird know that its call was attended to. Approaching the bees' nest, it flew shorter distances, and repeated its note with greater earnestness. On arriving at the cleft of the rock, the hollow tree, or cavity in the ground, it hovered over the spot for a few seconds, and then perched in silence on some neighbouring tree or bush, awaiting results. A small piece of comb containing young bees was generally left on the ground as a reward to the bird for its information. Bushmen searching for honey say that the bee-hunter must not be too generous at first, but merely give enough to stimulate the bird's appetite, when the shrewd little thing will show a second hive if there be another in the neighbourhood.

The above might be a very clear illustration of the fact that animals are also individuals. It is only a matter of being able to communicate with them. Bushmen could comprehend a bit of the bird communication towards them. Even though they might have had the capability to decode or understand the communication between or among the birds.

QUOTE 1:

When we come to study the nature of some of their dances, their funeral rites, and some of their leading myths, we find that they possessed a traditionary belief that at some remote period the connexion between man and the lower animals was much closer and far more intimate than at present,...

QUOTE 2:

" That they are," continues the doctor, " to some extent like baboons is true, just as these are in some points frightfully human.”

The above words are quite evocative of the fact that they were very close to the animals, in that they could sort of read or sense their intentions, track them, sort of communicative with some of them, and could even live in some kind of symbiotic relationship with a few of them. In fact, they were human beings who had the capability to exist as a sort of link between the animal world and that of the human world. After all, animals are apart from human beings only because of the communication problem. In fact, even in South Asia, many human populations had been treated or defined or considered as half animal or semi-human.

These were the lower caste populations such as the Pulaya, Pariah and such others. However, with the advent of the English rule in the subcontinent, all of them were liberated from their semi-human state. However, it was an act for which the higher castes of the location still cannot forgive the English. In fact, there is one rascal member of these higher caste populations who has made a mark on the national psyche by demanding that Britain should pay adequate compensation for what it had done in the Subcontinent.

If the English rule had taken the effort to bring in communication ability in some of the shackled animals of the subcontinent, such as the elephant etc. they too would have entered into close proximity with the human races.

when, as they believed, men and animals consorted on more equal terms than they themselves, and used a kindred speech understood by all!

One cannot say if these kinds of talk are insane talk. For, it is possible that some thousands of years back the ancestors of the Bushmen might have had better living standards. How they came to be entrapped in a forest region, and all such things would have very complicated history. The state of the animals also might have been different in a social system where in technical skills were different. In fact, in days to come when software technology improves to such a level that it is possible to communicate with many kinds of animals, those animal stature will change. Many may even enter into the capability of using sophisticated gadgetry.

Last edited by VED on Wed Dec 06, 2023 4:35 pm, edited 2 times in total.

6

c6 #

How the Bushmen was treated by the native tribes of Africa and by the Boers

How the Bushmen was treated by the native tribes of Africa and by the Boers

QUOTE: These unhappy fugitives at last became so terrified at the sight of any human being that there were portions of the country where they concealed themselves so effectually that a traveller might pass through its length and breadth without seeing a single soul, or even, if he were not aware of the fact, suspecting that it was inhabited.

END OF QUOTE

In this book, the Bushmen are mentioned as the entity which has been wronged by the others. Here the others are not the Boers alone, but almost all the native populations of Africa who came to occupy the traditional lands of the Bushmen. Every one of them has been quite wicked in the way their dealt with the Bushmen. In fact, they were treated in the same manner as gathering of poisonous snakes in a locality near to human habitation.

QUOTE 1: The Bushmen of Southern Africa have been described by their enemies, not only as being " the lowest of the low," but as the most treacherous, vindictive, and untameable savages on the face of the earth : a race void of all generous impulses, and little removed from the wild beasts with which they associated, one only fitted to be exterminated like noxious vermin, as a blot upon nature, upon whom kindness and forbearance were equally misplaced and thrown away.

QUOTE 2: On the one hand the Basutus slew them without mercy, whenever any of the marauders fell into their hands. The Baphuti chief Morosi, who was himself a half caste by his mother's side, destroyed the men of entire clans in order that he and his people might possess the women and girls, and only a few years before his death he made a grand final raid upon their remaining strongholds, when some hundreds of them perished, all the surviving females were captured, and the remnant of the unhappy fugitives was forcibly amalgamated into his tribe.

QUOTE 3: The massacre of many hundreds of these miserable creatures, and the carrying away of their children into servitude, seemed to be considered by him and his companions as perfectly lawful, just, and necessary, and as meritorious service done to the public, of which they had no more cause to be ashamed than a brave soldier of having distinguished himself against the enemies of his country

QUOTE 4: A war of extermination was commenced against them by the Koranas. Many of the Bushmen, he said, were shot

QUOTE 5: when closely pursued they would take refuge in dens and caves, in which their enemies have sometimes smothered scores to death, blocking up the entrance with brushwood, and setting it on fire.

QUOTE 6: The government apparently, without any further examination, acceded to the strong representations, and recklessly issued orders which proved the death-warrant of several hundred unhappy wretches, many of whom must have been perfectly innocent of the crime so sweepingly ascribed to them.

QUOTE 7: In this report it is stated that the Griquas have been accused, and with much probability of truth, of having whilst in a savage state treated the Bushmen with barbarity, and expelled them from the greater part of their country.

QUOTE 8: " These coverts enable the Bushmen to lurk here, in spite of all the efforts of the Griquas to root them out. They are a great annoyance to the latter, as well as to the other pastoral tribes in their vicinity, and they are consequently pursued by them, equally as by the Boers, with the utmost animosity."

QUOTE 9: that the Bastaards perpetrated the most horrid cruelties upon his nation, that when they had overpowered a Bushman kraal they would make a large fire and throw in all the children and lambs and kids they could not take away with them, and if they could by any chance lay hands on a grown-up Bushman they would cut his throat ;

QUOTE 10: " A party of Bushmen who had taken refuge in a cave refused to surrender ; they were destroyed," says Mr. Backhouse, " by setting on fire fuel collected at the cave's mouth ! "

QUOTE 11: One was not prepared to meet with such a display of genuine feeling as this among people who have been looked upon and treated as such untamably vicious animals as this doomed race are said to be.

QUOTE 12: In the same locality two or three villages of Bachoana Bushmen were found, "a people greatly despised by all the surrounding tribes."

QUOTE 13: When the Batlapin attack a Bushman kraal to revenge robberies of cattle, they kill without distinction men, women, and children ; women, they say, to prevent them breeding more thieves, and children to prevent them from becoming like their parents !

END OF QUOTEs

The Boers were also quite terrible towards the Bushmen. In fact, they treated them like snakes and killed them remorselessly.

Here it might be correct to delve upon the emerging White race versus other races issue. Historically as well as actually the native-English were different from most other white populations. In fact, they were different from almost all other human populations. The reason for this can be traced into the verbal codes inside pristine-English.

However, there is this information that might be needed to be mentioned here. The Boers and the native populations of Africa saw the Bushmen as some kind of poisonous beings. There are hints in this book that the native-English side did have a more benign attitude to them. Since I have not yet read about the later years, I cannot say anything more here with any level of certitude.

END OF QUOTE

In this book, the Bushmen are mentioned as the entity which has been wronged by the others. Here the others are not the Boers alone, but almost all the native populations of Africa who came to occupy the traditional lands of the Bushmen. Every one of them has been quite wicked in the way their dealt with the Bushmen. In fact, they were treated in the same manner as gathering of poisonous snakes in a locality near to human habitation.

QUOTE 1: The Bushmen of Southern Africa have been described by their enemies, not only as being " the lowest of the low," but as the most treacherous, vindictive, and untameable savages on the face of the earth : a race void of all generous impulses, and little removed from the wild beasts with which they associated, one only fitted to be exterminated like noxious vermin, as a blot upon nature, upon whom kindness and forbearance were equally misplaced and thrown away.

QUOTE 2: On the one hand the Basutus slew them without mercy, whenever any of the marauders fell into their hands. The Baphuti chief Morosi, who was himself a half caste by his mother's side, destroyed the men of entire clans in order that he and his people might possess the women and girls, and only a few years before his death he made a grand final raid upon their remaining strongholds, when some hundreds of them perished, all the surviving females were captured, and the remnant of the unhappy fugitives was forcibly amalgamated into his tribe.

QUOTE 3: The massacre of many hundreds of these miserable creatures, and the carrying away of their children into servitude, seemed to be considered by him and his companions as perfectly lawful, just, and necessary, and as meritorious service done to the public, of which they had no more cause to be ashamed than a brave soldier of having distinguished himself against the enemies of his country

QUOTE 4: A war of extermination was commenced against them by the Koranas. Many of the Bushmen, he said, were shot

QUOTE 5: when closely pursued they would take refuge in dens and caves, in which their enemies have sometimes smothered scores to death, blocking up the entrance with brushwood, and setting it on fire.

QUOTE 6: The government apparently, without any further examination, acceded to the strong representations, and recklessly issued orders which proved the death-warrant of several hundred unhappy wretches, many of whom must have been perfectly innocent of the crime so sweepingly ascribed to them.

QUOTE 7: In this report it is stated that the Griquas have been accused, and with much probability of truth, of having whilst in a savage state treated the Bushmen with barbarity, and expelled them from the greater part of their country.

QUOTE 8: " These coverts enable the Bushmen to lurk here, in spite of all the efforts of the Griquas to root them out. They are a great annoyance to the latter, as well as to the other pastoral tribes in their vicinity, and they are consequently pursued by them, equally as by the Boers, with the utmost animosity."

QUOTE 9: that the Bastaards perpetrated the most horrid cruelties upon his nation, that when they had overpowered a Bushman kraal they would make a large fire and throw in all the children and lambs and kids they could not take away with them, and if they could by any chance lay hands on a grown-up Bushman they would cut his throat ;

QUOTE 10: " A party of Bushmen who had taken refuge in a cave refused to surrender ; they were destroyed," says Mr. Backhouse, " by setting on fire fuel collected at the cave's mouth ! "

QUOTE 11: One was not prepared to meet with such a display of genuine feeling as this among people who have been looked upon and treated as such untamably vicious animals as this doomed race are said to be.

QUOTE 12: In the same locality two or three villages of Bachoana Bushmen were found, "a people greatly despised by all the surrounding tribes."

QUOTE 13: When the Batlapin attack a Bushman kraal to revenge robberies of cattle, they kill without distinction men, women, and children ; women, they say, to prevent them breeding more thieves, and children to prevent them from becoming like their parents !

END OF QUOTEs

The Boers were also quite terrible towards the Bushmen. In fact, they treated them like snakes and killed them remorselessly.

Here it might be correct to delve upon the emerging White race versus other races issue. Historically as well as actually the native-English were different from most other white populations. In fact, they were different from almost all other human populations. The reason for this can be traced into the verbal codes inside pristine-English.

However, there is this information that might be needed to be mentioned here. The Boers and the native populations of Africa saw the Bushmen as some kind of poisonous beings. There are hints in this book that the native-English side did have a more benign attitude to them. Since I have not yet read about the later years, I cannot say anything more here with any level of certitude.

Last edited by VED on Wed Dec 06, 2023 4:35 pm, edited 3 times in total.

7

c7 #

Serpent worship

Serpent worship

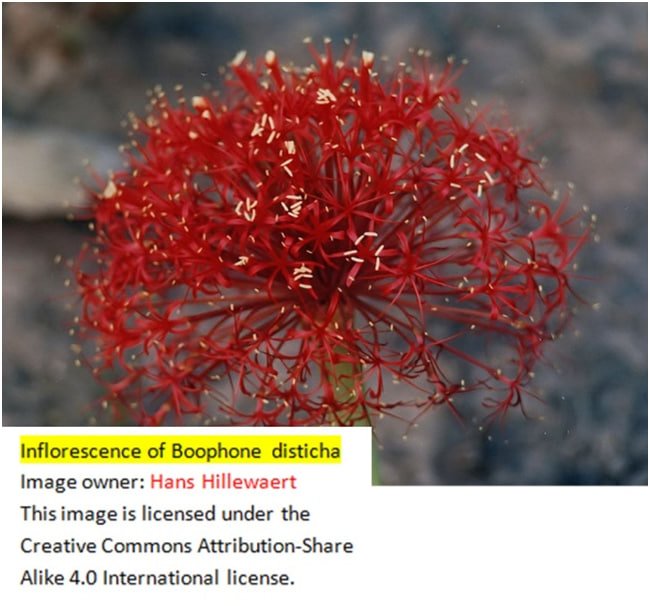

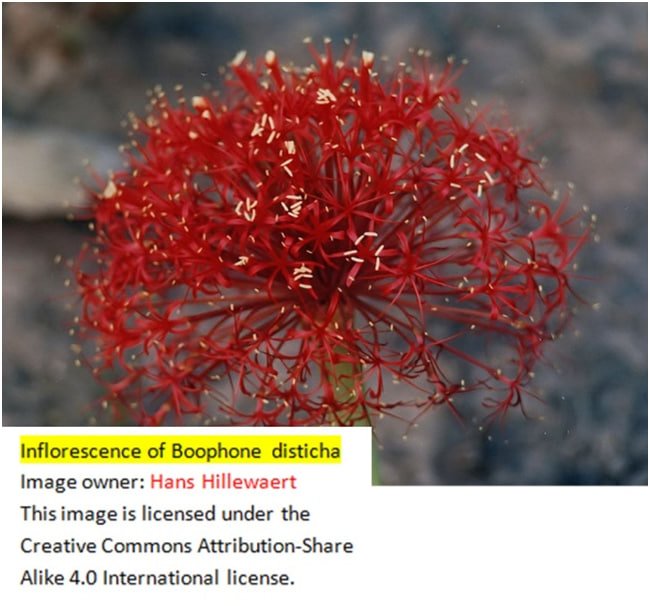

However, British-India did have a similar issue. However, this was with regard to real poisonous snakes. There were many locations inside the subcontinent wherein serpents were worshipped as divinities, propitiation of which could give benevolent results. I do not want to give any feeling that I find these kinds of attitude foolish. For, one can mention anything with certainty only if one is actually aware of such things as the Codes of reality, and the software codes of life. Interested readers are requested to read my book: Software codes of mantra, tantra, witchcraft, black magic, evil eye, evil tongue &c.

In Travancore kingdom in the southern most end of the South Asian subcontinent, serpents were worshipped. Usually it is the cobra which is worshipped, even though the term Naga might or might not be the divine serpent. In many medium level higher caste households, a plot of land is kept apart for their worship. In some houses, cobra families used to live.

REV. SAMUEL MATEER mentions them as quite dangerous, even though he says thus also: