17. Scattered thoughts in my mind

17. Scattered thoughts in my mind

Written by VED from VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

Previous page - Next page

Previous page - Next page

Vol 1 to Vol 3 have been translated into English by me directly.

From Vol 4 onward, the translation has been done by a translation software. So there can be slight errors in the text.

It was slightly difficult to make the translation software to understand that in Indian languages, there are hierarchy of words everywhere.

From Vol 4 onward, the translation has been done by a translation software. So there can be slight errors in the text.

It was slightly difficult to make the translation software to understand that in Indian languages, there are hierarchy of words everywhere.

Last edited by VED on Sat Aug 09, 2025 12:43 pm, edited 5 times in total.

Contents

1. A matter which trivial English cannot achieve

2. What can be done from a distant background

3. The analogy of the beehive

4. Dual demeanour

5. Convention and efficiency

6. The land of cunning minds and beastly dispositions

7. Upper class - lower class

8. To make a gentleman a warrior

9. To purify the wicked

10. On learning multiple languages

11. The condition of releasing toxic fumes

12. The spider web of language and the train accident

13. Into the backstory of mental disorders

14. To make the exalted a fool

15. The gems from antiquity

16. The public examination system for government job

17. On the futility of educational qualifications

18. The offensive word - Ningal (stature neutral you in Malayalam)

19. The true nature of the royal family

20. Comparing the official systems

21. Officialdom and police heritage in Travancore

22. On turning British-Malabaris into Keralites

23. Roots of official misconduct

24. Watching the dance without knowing the story

25. The power of officials

26. The clash of two vile cruelties

27. A land’s stench can be traced through its laws

28. The plight of the lower castes

29. Brutal officials in a brutal kingdom

30. History of ethnicity scrubbed out into oblivion

31. Police and custodial interrogation

32. The police system in Travancore

33. Reforms with only superficial changes

34. A Police Act in British-India

35. Organised resistance and language codes

36. Creating a governance system with high social equality

37. The officials left in the lurch by the English rule

38. Various government positions

39. Fearsome-sounding official titles

40. Matters in Malabar

41. About the piling up of blunders

42. That not even a single paisa will be increased

43. English Official Procedures

44. Human rights of government officials

45. When the reins of Malayalam words are unleashed

46. This language which has a hypocritical mindset has to be banished

47. The language and words that induce epileptic seizures

48. Mansabdari in words

49. The Satanic language is the problem

50. Auspiciousness and inauspiciousness signs displayed by individuals

Last edited by VED on Sun Jun 22, 2025 6:07 pm, edited 7 times in total.

1. A matter which trivial English cannot achieve

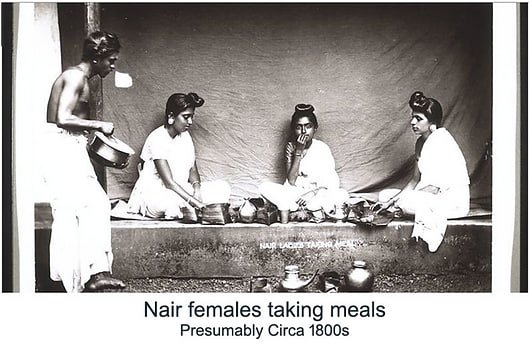

Look at this provided image. It is a painting from 1800 or thereabouts. You can see a servant serving food to Nair women. This person is likely a Nair individual as well. Nevertheless, the title of a servant of the superiors is evident on this person.

In this person, you can observe a mechanical bow, a stoop, or some other servile gesture. This is a gesture that shapes the design of linguistic words. If this gesture is expressed, it suggests to the superior that a Nee - Ingal personal relationship exists.

At the same time, if this servant behaves without bowing, it might create an impression that this person is addressing someone who should be called Saar as Ningal. In other words, it’s akin to an ordinary person addressing a government official as Ningal.

This is something a government official would not tolerate. The reason being, they prefer the gesture mentioned earlier. A Ningal - Ningal relationship is unbearable for them.

Sometimes, the subordinate who behaves without bowing might even evoke a sense in the superior that they are being addressed as Nee. In other words, an outright insolent. This is not something that can be permitted in any way.

The reality here is that the subordinate person has not used any words at all. Instead, they simply did not bow their head or body. This creates significant ebbs and flows in linguistic words.

This phenomenon can be defined, if you will, as a non-verbal signal. It is indeed a significant matter in feudal languages.

In complaints like, “I didn’t say anything bad, yet he got very angry with me,” such a factor often plays a role.

In husband-wife relationships, worker-employer relationships, police behaviour, government clerks’ conduct, and many other contexts, such a matter can cause major outbursts.

However, creating such an explosive non-verbal signal in the English language is indeed difficult. To achieve such an outburst in English, one would need to carefully orchestrate deliberate steps.

From here, I move directly to another matter: the phenomenon of the mental platform, or the mental upper tier or lower tier.

In feudal languages, individuals are said to stand on various rungs of a ladder, from Inhi👇 to Ingal👆, put very simply.

This exists as a mental state in individuals. For example, “I am a doctor,” “I am an IPS officer,” “I am a police constable,” “I am a teacher”—such languages establish a sense of superiority in the respective individuals.

This kind of upper-tier mentality is usually very firm. In feudal language regions, people strive hard to acquire and stand on such a firm mental platform.

The reason is that if one manages to secure such a platform, no remarks from others can dislodge them from it.

Words like Saar, Doctor, Maadam remain unshaken on their platform. Words like Adheham, Avaru, Oru, Olu cannot, in ordinary circumstances, be displaced by minor slanderous stories.

However, the situation is entirely opposite for those who fail to secure such a platform. Individuals referred to as Avan, Aval, Onu, Olu can be spoken about in any manner. In other words, they suffer from a profound lack of strength.

A person in the Ayaal position has less positional strength. A small slanderous story is enough to push them into the pit of Onu or Olu.

Yet, many individuals in society who lack such a high formal platform live on a good mental platform. To maintain their platform at an elevated level, they or those standing with them must act strategically and efficiently.

Connections with high-status individuals, indications of great financial strength, stories of receiving grand respect, or holding a highly prestigious job position—these must be spread in society, both explicitly and implicitly, through conversations and hints.

This must be provided most powerfully to individuals of lower status in society or nearby areas. Their respect is an absolutely essential nourishing element in feudal languages. If they lack respect for you, your position is as good as finished.

Sometimes, the hints given in this manner may be hollow. Ordinarily, this poses no danger. However, a companion who, unintentionally or otherwise, reveals that such hints are hollow through words or suggestions is indeed dangerous.

For example, I say to a socially lower-status person living nearby, “I bought this car.” Then they respond, “Your friend told me this car was only given to you temporarily by your uncle!”

What happens here is that, through various verbal hints, a few of the bamboo poles on which a person stands above the social pit are cut from below. The person quickly falls into a socially dangerous pit, a state that spreads through words in society.

This can also impact the spoken codes associated with that person’s other family members. It’s enough to turn a wife from Oru to Olu.

It’s also worth noting that such mental disturbance does not exist in the English language. No matter what anyone says, words like “You,” “Your,” “Yours,” “He,” “His,” “Him,” “She,” “Her,” “Hers” remain unshaken. Personal relationship links do not budge.

Let me illustrate this with an example once more.

A person’s elder sister married a high-status individual in society. In other words, this person is the younger brother of Oru or Adheham’s wife.

However, this person’s younger sister married someone defined by low-value words in the local language. In other words, this person is the elder brother of Onu or Avan’s wife.

This person gets into a problem. At the place where the issue occurs, everyone knows this person is the younger brother of Oru or Adheham’s wife. This provides them with significant protection. However, neither this person’s elder sister nor her husband comes to the scene of the issue. There’s no need for that. Merely indicating their connection is sufficient.

At the place where the problem occurs, it’s this person’s younger sister and her husband who show up. They come to help. However, they commit a grave assault in terms of spoken codes.

“Is this the elder brother of Onu’s wife? Is Olu his younger sister?”

With this, the reins of words are lost. Words like Eda, Nee enter the conversation. A direct blow to the face might even occur.

No such disturbances are possible in the trivial language of English.

2. What can be done from a distant background

The matter I am about to discuss was intended to be included in the previous writing but was omitted.

An IPS officer, both in their professional domain and in private settings, remains an IPS officer. In other words, when this person is seated in their professional arena, no one can suddenly, from some distant place, reduce them to the rank of a police constable.

Such occupational positions are inherently secure in this manner.

Similarly, a household servant, regardless of the setting, remains a household servant. No one can suddenly, from a distant platform, elevate this person to an IPS officer.

The mental states of both these groups, as well as how others evaluate them, are firmly inscribed in local feudal language word codes, as if written on a rock with a steel tool.

However, for individuals operating in society without any positional status, such a rock-solid social standing is nowhere to be found. Remember, this pertains to the context of a feudal language social environment.

Such individuals are rare in society. This is because most people operate from some secure positional status. This helps each individual project a distinct personality.

Yet, some individuals, without any support from social or occupational positions, proclaim a lofty personality and operate across various platforms. From an English perspective, this is a common matter.

However, in feudal language regions, this is a form of deception. If people recognise this person’s lack of positional security, they will mockingly point it out. Who does he think he is?

This is one aspect of the matter.

There is another side to this same issue.

Some individuals may have dual social standings in the background—one of great eminence and another of diminished status. However, they may lack a position that clearly grants them a defined status. Nevertheless, they use their own personality and other attributes to operate on lofty platforms and get things done.

The dual standings in their background exist as a dangerous physical reality. When such a person operates in a highly serious professional domain with an air of great eminence, certain significant individuals in the background pull their status down to a lower level. How this is done is not detailed here.

Imagine the scenario where an IPS officer, confronting a major social upheaval with the eminence of their professional position, is suddenly reduced to a police constable from the background. The IPS officer becomes ineffectual. The task they were handling falls into disarray.

A person of great intellectual strength can be seen transforming, in a mere moment, into a feeble, enervated individual. Such a development typically affects those who, without maintaining or being able to maintain a clear social platform, operate while proclaiming an aura of lofty intellectual exchange.

What has been described is a physical reality. In other words, the truth is that behind physical reality lies a transcendental software platform that binds everything together.

In feudal languages, individuals are connected to many others through various subservient links and other ties. These others have the power to either energise a person or render them inert.

From here, the writing points to another matter. That can be addressed in the next writing.

3. The analogy of the beehive

Just as we observe an ant colony or a beehive today, English individuals should have viewed South Asian crowds in a similar way. However, they lacked the insight to do so. They encountered people in South Asia, Africa, the American continent, and even continental Europe who bore a striking resemblance to their own physical nature.

Consider an ant colony.

Among those ants, there exist intricate social and personal relational links that are invisible and incomprehensible to us. Some ants may be great leaders, while many others belong to various subordinate classes. There may also exist intense loyalty, allegiance, subservience, and more among them. Yet, we cannot discern any information about these matters.

Similarly, when English people encountered South Asian populations in earlier times, they failed to grasp many aspects.

Personal relationships in feudal languages differ from those in English. Elder brother, elder sister, mother, father, younger brother, younger sister, teacher (male), teacher (female), neighbour (male), neighbour (female), and others are distinct in feudal languages compared to their English counterparts.

Likewise, wife, husband, their relatives, and friends are equally distinct.

In English, all such personal relationships lack any hierarchical codes, directional cues, or links that can pull or push someone out.

However, in South Asian languages, all such relationships are governed by Inhi - Ingal words that either stand firm like an immovable rock or toggle like a place experiencing constant tremors. These two words also influence the form and movement of countless other words.

If such fixed or unstable links, prone to positional shifts, existed only between two individuals, it would create a relatively minor complexity.

However, the web of links across all the personal relationships mentioned above resembles a beehive teeming with bees, buzzing, frothing, and humming.

Some strive to maintain the hierarchy in each link, while others attempt to dismantle it, aiming to establish a new link that places them higher. This process may occur silently and covertly at times, or openly with great fanfare at others.

This beehive phenomenon is not something observable in an English language social environment.

For this reason, workplaces, marital relationships, and other contexts in a feudal language social environment possess a profound complexity unimaginable in English.

Small-scale words can wield immense power in critical positions, much like pulling the trigger of a gun with a slight press of a finger. But when the trigger is pulled, the gun fires. A massive explosion may occur, potentially causing injury or harm to another.

One thing worth mentioning here is the concept of kuthithiripp (backbiting). It’s unclear if there’s an equivalent English term for this.

In feudal languages, this kuthithiripp seems tied to the oscillations of eminence and degradation within word codes.

Referring to someone previously addressed as Saar as Ayaal, or someone addressed as Ayaal as Avan, even with an innocent or utterly pure demeanour, can cause a seismic shift in personal standings.

However, the matter I intended to address here is something else.

In a personal relationship community buzzing like a beehive, if a critical positional shift in word codes occurs at a decisive point for an individual, it can affect their mind, personality, mental state, and physical energy.

Imagine an IPS officer leading hundreds of police constables in a situation requiring great leadership skill. Suddenly, the sensation of being demoted to a constable rank enters their mind and energy as a software coding.

While this scenario may seem improbable, many equivalent situations are possible in feudal language personal relationships.

Before concluding today’s writing, let me recall a song from the film Chemmeen.

The song Pennaale Pennaale.

In a feudal language environment, marital relationships contain personal relational links, with codes of loyalty, allegiance, closeness, distance, deceit, and betrayal, that surpass what can be imagined in English.

When translated into English, such actions may appear devoid of any deceit.

A slight elongation or shortening of these links, or a minor pull in any direction across 360°, can cause strengthening or weakening in the connected individual.

If a wife stands and shows subservience (respect) in the presence of someone competing with her husband in word codes, it can cause a depletion of energy in the husband’s physical being. Many such scenarios exist, which we can explore later.

Song Lyrics Translation: Not errorfree

In olden times, a fisherman went for pearls,

Lost in the western wind’s dive.

His waist-bound girl sat in penance,

And the sea mother brought him back.

If the fisherman goes in his boat,

You are his guardian, oh!

Hoy, hoy!

Your man, your man, isn’t he your husband?

Or he won’t see the shore.

Oh girl, oh lapwing-eyed girl, dark-fish-eyed girl!

4. Dual demeanour

Let me begin today’s writing by discussing the concept of kuthithiripp (backbiting) mentioned in the previous writing. In feudal languages, this is indeed a perennial phenomenon. While something similar can be done in English, the mental predisposition that naturally inspires or provokes such behaviour is absent there. English lacks the word codes that facilitate this.

A society in a feudal language is a complex collection of 3D webs. The links in these webs consist of various levels of indicant verbal codes. While one might say that the most fundamental words among these indicant verbal codes are Nee, Ningal, and Thaankal, in reality, their shadows and influence persist in the various forms and expressions of thousands of other words.

The words Ingu vaa (come here) themselves, when paired with Nee, Ningal, or Thaankal, undergo changes in form and tone.

Although English lacks a similar phenomenon, the words “You come here” can be modified to “Can you please come here?” or “Could you please come here?” to introduce slight variations in expression and corresponding tonal shifts.

However, in a large web of English-speaking individuals, such changes do not cause significant tension or structural shifts.

In feudal languages, the situation is entirely different. In feudal languages, a large group of people is interconnected by You, He, and She words of varying levels.

Here, the phenomenon of kuthithiripp often operates by expressing opinions about individuals or by sharing private or previously unknown information about them.

This action activates a mechanism in feudal languages that does not exist in English.

To put it simply, an individual may shift from Avan to Adheham or Oru, or from Adheham or Oru to Avan. However, even without changes to words like Adheham or Avan, the numerical strength of the codes within their inner layers can shift.

A change in the word codes associated with one person alters the form and expression of numerous related words. Moreover, it affects the word codes linked to other individuals connected to that person. Some may shift from Avan to Adheham, or the reverse may occur.

This can create an experience where the entire web of people sways and trembles.

In feudal languages, every organisation has a flow of focus directed upward from the bottom. This flow moves through everyone in the organisation toward the top. If an individual with a mental disposition contrary to this flow joins the organisation, words, tones, information, and more that oppose this flow will spread from that person into the organisation.

If the upward flow is strong, others will push this disruptive individual out. Otherwise, that person may spread a state of malaise within the organisation.

Let me mention another matter related to individuals joining organisations. When a person joins an English organisation devoid of any hierarchy, their natural character and behaviour remain largely unchanged. This is because others within the organisation address and refer to them in the same way as people in the outside world.

However, when a person joins an organisation in a feudal language, they undergo immediate mental, personal, and body-language transformations.

In the outside world, this person may be addressed by others as elder brother, younger brother, Adheham, Avan, Thaankal, Ningal, Nee, and more. They live with a specific mental and personal disposition that shifts according to the context of these interactions.

But upon joining the organisation, this person continues to live bound by a variety of links distinct from the word-based relational links of the outside world.

Feudal languages are languages that proclaim and project big person and small person in every word.

If a person who was a big person outside becomes a small person within the organisation, it can cause significant mental distress.

If a person who was a small person outside becomes a big person within the organisation, the word codes may create a dominant mindset in their psyche.

Which rung on the Inhi👇 - Ingal👆 ladder a person occupies when joining the organisation, and what their word-based position was on that rung, is a major factor. I won’t delve into that here.

Simply put, the person inside the organisation is often markedly different from the same person outside.

Another related point is that within the organisation, a person does not operate or behave as an individual.

Inside the organisation, that person becomes part of a larger link. In feudal languages, a person is not an independent individual with a free personality as imagined in English.

Walter Lawrence, an English official in British-India, observed the social environment in Kashmir and reportedly described it as follows:

Kashmiri Pandit officials may have been individually gentle and intelligent; as a body, they were cruel and oppressive.

The Kashmiri Pandits referred to here are the Brahmins of the region. As individuals, they are highly refined people. However, toward the communities under their control, they behave collectively with great harshness and cruelty.

This, too, is a distorted disposition created by feudal languages.

In everyone who speaks feudal languages, this dual nature persists.

5. Convention and efficiency

This writing currently focuses on describing the inner coding of feudal languages. While addressing the Mappila Rebellion in South Malabar, I briefly began writing about the invisible yet immensely powerful coding in the local language of this region, which has turned into a lengthy discourse.

Some matters being written now may have been touched upon earlier.

This writing continues. After this section, I plan to return to history.

Most aspects of local feudal languages differ from English. In fact, one could even consider English people and feudal language people as two distinct species. However, as English people poured all their resources into feudal language communities, both groups began to feel there was little difference between them.

The social standing and claims of various South Asian communities shifted with the arrival of British-India. I won’t delve into that now.

Let me first discuss individual efficiency. Among an ordinary crowd speaking only English, there exists a general standard of efficiency. Upon closer inspection, variations and differences may arise due to each individual’s interest in their work, skill, and other factors.

However, the situation is different for a group of ordinary individuals speaking a feudal language.

A mental focus, almost entirely absent in English, persists within them. Every action they take, every person they interact with, every occupational position they hold, and more, is governed by the thought of whether it will positively or negatively affect word codes.

The foundation of this thought is whether their actions will make them Adheham, Ayaal, or Avan.

Joining a particular occupational position raises the question of whether they will fall under Adheham, Ayaal, or Avan. This is closely tied to a state of anxiety—a profound anxiety, indeed.

Indicating a particular relationship also raises the question of whether it will make them Adheham, Ayaal, or Avan.

While these may seem trivial when written here, in reality, those operating in expansive social and professional arenas know well that such matters significantly influence behaviours and actions, positively or negatively. Doors open or close based on how others evaluate these factors.

Ordinary individuals speaking only English, operating in various positions among their peers, do not experience this mental confusion. Words do not create significant hierarchical shifts between individuals.

However, in feudal languages, even among ordinary people, various personal relational links exist. Joining any occupational position can result in feelings of tension, pressure, and more within these links.

The focus here is on efficiency, though the writing seems to veer in another direction. Let me return to efficiency.

In feudal languages, every individual in their operational arena carries an air of subservience and dominance. Even in the lowest social or occupational arenas, individuals maintain this mental disposition.

Among English people, the concept of a socially degraded occupation does not exist in word codes. However, a lack of interest in a job may exist, but it does not cause shifts in language.

In feudal languages, there is a concept called keezhvazhakkam (convention). It is often said to be the Malayalam equivalent of the English word “convention,” which is accurate in many contexts.

However, in feudal languages, this word does not align perfectly with that translation.

In every occupational, social, or familial position, an individual operates and behaves most efficiently when in harmony with the subservience-dominance relational coding. This is the keezhvazhakkam of such positions. Adhering to this convention is what manifests as the highest efficiency in that individual.

Correcting flaws or errors in the operational arena, identifying such issues, and informing others is not seen as efficiency. Instead, it is perceived as a disruptive mindset.

Alternatively, it may create the impression that the individual is trying to elevate themselves.

This is not an incorrect perception either. The nature of language words can only interpret such behavioural errors or operational flaws in this way.

Avan correcting Adheham is an act of defiance and creates an explosion in the flow of communication.

Adhering to established conventions often leads to significant personal successes.

However, systems and operational arenas become filled with uncorrected errors.

At the same time, while English systems may also accumulate various errors, individuals in various positions continuously correct them.

However, if more than one feudal language individual is placed in any part of an English system, errors may begin to accumulate uncorrected. Moreover, negative mental dispositions may creep into individuals’ mindsets. That space ceases to be an English mental arena.

6. The land of cunning minds and beastly dispositions

Locally insignificant Indians go to English-speaking nations. There, they display remarkable abilities. People, both in India and from afar, loudly proclaim that Indians possess such great skill and talent. Indian online media constantly trumpet this fact.

However, the reality is broader. In English-speaking nations, individuals from Africa, South America, continental Europe, Middle Eastern countries, the Far East, South Asia, and beyond frequently exhibit similar abilities and personalities, growing explosively in lofty directions—a common sight in these nations.

It’s worth considering why Indians, who display such ability and personality in English-speaking nations, cannot do the same in their native South Asia.

There is another side to this. Today, in India, Indians and citizens of other third-world nations demonstrate great expertise in the IT sector. That topic is not being discussed here.

This discussion could be framed by imagining rats and ants given technical skills and advanced tools. However, this writing does not intend to pursue that path.

I know firsthand that India has many individuals with profound English proficiency, exceptional communication skills, and more. However, these individuals can only operate in this country by confining their lightning-fast communication and the efficiency it brings within their own circles.

As an example, I had an experience around 2007.

I contacted the Indian office of an internationally operating IT company for technical support. I spoke rapidly with various technicians, switching between them. However, it was discovered that the core of the technical issue lay with an IT department owned by the Indian government.

Until then, all technicians and customer support staff had communicated in English, addressing each other by name without any hierarchical distinctions.

But when Indian government IT department officials entered the scene, everything turned chaotic. They operated in the local language, exuding a sense of great eminence. Speaking with them was difficult. While they knew English, their dominant disposition was rooted in the local feudal language.

The efficiency of the IT company’s technical support collapsed at this juncture.

A kind of anxiety, absent in English-speaking arenas, persists in many Malayalam-speaking arenas. However, in lofty arenas where hierarchies stand firm like rock, this anxiety is absent.

This anxiety affects the precision required in individuals’ work. Often, people hesitate to ask questions that could avoid errors, even when opportunities arise.

One reason may be the mental turmoil within. Alternatively, it could be the need to express subservience in words. Or it might be uncertainty about whether they or the other person holds a higher position in word codes.

Let me share a firsthand experience.

During the initial phase of the Aadhaar Card project, I completed the biometric process for a young person’s Aadhaar Card. When asked for the name, I provided it. When the Aadhaar Card arrived, there was a spelling error in the name written in English. This became a serious issue, as it would affect other related documents. Correcting the Aadhaar Card posed several difficulties for various reasons.

What I observed was that many individuals operating in the local language environment repeated such spelling errors. None of them had the disposition to confirm the spelling before writing it. The spelling they wrote bore no relation to the actual name—it was simply what they assumed.

It’s easy to ask questions of those who clearly display subservience. However, there’s reluctance to ask those who don’t stand on this path.

In government departments, many individuals make various errors. The reason isn’t a lack of skill or knowledge. Rather, it’s the absence of the natural refinement found in English speakers and the fact that they operate in a feudal language environment.

I haven’t felt that English individuals possess extraordinary knowledge or wisdom. Such extraordinary knowledge isn’t necessary. What’s needed is a language environment that allows courteous, continuous communication. With this, much of individuals’ anxiety would vanish.

Having read Kalidasa’s works or the Bhagavad Gita, or holding a doctorate in quantum physics, doesn’t bring the natural refinement of English speakers to an individual.

The operational experience of Indians living in English-speaking nations is entirely different.

In India, a competitive mindset prevails among people in all matters.

Who is he? Who does he think he is?

If he gets this, even his wife will become arrogant. Then what will her attitude be?

He needs to be put in his place before giving this to him. Otherwise, he won’t value it or us.

This mindset of arrogance and value is absent in English.

The English word for “arrogance” is arrogance. There may be arrogant people in English.

However, in Malayalam, the phenomenon of “ahankaaram” (arrogance) is created by the hierarchical nature of Malayalam words. Thus, this form of arrogance is not seen in English.

An ordinary person enters a government office in India. If the person is willing to stand beneath the hierarchies among the staff, no major issues arise. Still, the staff may try to suppress them, finding satisfaction in doing so.

If the person refuses to stand beneath these hierarchies, the atmosphere turns harsh. This is because someone defined as Avan is trying to act superior. He must be subdued to move forward.

This experience doesn’t occur in a government office in an English-speaking nation.

An ordinary person enters an Indian police station. The lowest-ranking police personnel are present. The visitor must display deference in body language and words. Even so, most people are addressed with low-level words like Nee, Avan, or Aval by police, including constables.

In English-speaking nations, a person entering a police station can sit with their personality intact. The police there are obligated to adhere to the definition of “gentlemen” in the English language.

In India, police must behave discourteously in a feudal language to gain respect. A retired IPS officer stated in a YouTube video that people will only obey if treated discourteously.

In English, obedience itself is a different concept, which I won’t explore now.

Many believe the excellence in English-speaking nations stems from advanced technology and economic strength. That’s not the true reason.

Their true excellence lies in the fact that people there don’t live or operate under feudal languages like those in India or in such linguistic environments.

An Indian in an English language environment may appear to have great skill and personality, which may be true. But it’s the English language environment that enables this.

In the US, Sundar Pichai, a top Google executive, addresses the American President as Mr. followed by their name. This is because Google operates in an English-speaking nation.

If Google were relocated to India, even Pichai couldn’t address a mere police constable as Mr. followed by their name. It might work initially, but once the American image fades, Pichai is just another Indian.

No need to mention those working in lower positions at Google. If they tried to act superior in an Indian police station, they’d not only get slapped but other Indians would applaud the police.

The situation for an ordinary person entering government or private hospitals in India deserves separate discussion.

Even while saying all this, we must remember that anyone entering any arena is a local individual. The disposition burning within them is shaped by the local feudal language. It’s this that other organisational members react to with opposition, defense, or counterattack.

Life in India requires navigating with cunning tactics against various individuals. The ability and intelligence of a person lie in navigating this way, earning high praise from others.

In a feudal language, every individual views those beneath them like a hawk views its prey. They wound the prey and ensure it remains pinned under their talons, never letting it escape.

Thus, India today is a land of cunning minds and beastly dispositions. The fault lies not in the individual but in the language.

When these people go to English-speaking nations, they experience a sense of landing in paradise.

However, their linguistic disposition and cunning may sometimes manifest there too. When this happens, English speakers perceive it as a ferocious, terrifying presence—an incomprehensible, menacing entity infiltrating their midst.

7. Upper class - lower class

Today, I plan to write some scattered thoughts.

The first among these is the social concept of the upper class. At a glance, this concept seems to exist in every social environment. It is visible in England too. However, when England’s upper class interacts with the common class, words do not carry a significant feudal tone.

What I refer to here is the interaction between England’s royal family, noble families, and ordinary people. Nevertheless, specific words and phrases have been crafted in English for this purpose. Some have argued to me that this itself proves a feudal character in the English language. We can explore that later.

There are specific words used only for addressing the king, queen, royal family, nobles, and their families. However, these words do not typically affect or influence the ordinary English words You, Your, Yours, He, His, Him, She, Her, Hers, or the thousands of other words associated with them.

That’s not the focus of this discussion.

The reason is as follows. Centuries ago, a European continental king invaded England and established dominance. How long this lasted is unclear. But this led to a continental European upper-class dominance in England. While these rulers may have become English speakers, the presence of these non-native English individuals persisted in England’s upper echelons.

Moreover, within Britain, Ireland, Scotland, India, and Wales—three Indian regions—coexisted alongside England, with Hindi.

These factors remained blemishes on the purity and clarity of the English language.

We can’t delve into that now either.

What I meant to say is that, in reality, the concept of an English people does not exist in the English language. Instead, there are occupational positions and familial roles. These do not influence the ordinary words You, Your, Yours, Avan, His, Adhehamal, Avalol, Ayan, or Her, or the thousands of associated words.

In English, words like Sir, Madam (Ma’am), Mr., Mrs., Jehovah, and Miss. exist. There’s much to say about these, but I won’t go there.

These words are typically used at the start of an address for someone of higher status. However, they do not affect or influence the ordinary words You, Your, Yours, He, His, Avan, She, Her, Hers, Hersal, or Ayalal, or the thousands of associated words.

How obedience is enforced in an organisation is a question many have pondered. Most who think this way are feudal language speakers. Similarly, English organisations working closely with feudal language speakers have adopted many of their methods.

For example, the English East India Company. In its early days, its officials didn’t know Malabari or Malayalam. But within a few decades, some reached a level where they could handle these languages. The Company saw this as a great advancement.

In reality, this led to the Company’s decline. Its values and policies plummeted. This set the stage for its downfall.

The Company’s local officials in Malabar shaped many of its cultural standards. Some may have tried to impose local social subservience on English officials. More likely, they defined these English officials linguistically at the same level as traditional local rulers for the common people. The locals lacked the English knowledge to do otherwise.

This is how, in northern South Asia, English officials were elevated to the status of Saab and Memsahib.

While English officials may not have fully grasped this, they too may have gradually risen to lofty heights in the local language.

Today, things have changed. The work culture in many English/American companies operating in India is no longer shaped by people ignorant of English. Instead, local individuals with profound English proficiency work in these companies.

In many English/American companies in India, not only Sir and Madam (Ma’am) but also Mr., Mrs., and Miss. are absent from workplace communication.

In an American company with a major branch in India, everyone, including the CEO, addresses each other by first name. However, this company selects employees with great care, choosing those with high English proficiency and alignment with its linguistic culture.

If such companies hired individuals capable of passing IAS, IPS, UPSC, or PSC exams, they would inherit the culture of Indian government departments.

Another example is Queen Victoria. She was England’s queen. When the English royal family took British-India from the English East India Company, the title of mere queen became problematic. South Asian maharajas would not accept being under a mere queen’s protection. Their status would diminish before local peers.

Someone in India (British-India) likely suggested that Queen Victoria’s title in South Asia should be that of an empress. Thus, the title Empress of India was proclaimed.

Moving forward, if English people start various organisations worldwide, initially hire those with great English proficiency, and carefully select others to join, exceptional organisations would spread globally.

In such English organisations, both junior and senior employees would gain an intangible mental elevation. This is because, unlike in India today, language would not create an upper class or lower class.

To achieve this, they must completely reject local feudal language cultures.

8. To make a gentleman a warrior

Thoughts scattered in the mind continue to linger.

From the perspective of feudal language, it appears that the English were a crowd of people ignorant of the ways of the world and utterly naive. It seems that the modicum of discernment and wisdom that existed among them was due to the presence of Celtic language speakers intermingled within their midst.

Feudal language speakers do not attempt to uplift individuals who are socially, intellectually, or economically diminished. Even if they make such an effort, it is only after ensuring that this elevation does not affect their own status in linguistic terms.

There are certain hidden truths at play here. One of them is the ladder of Inhi👇 - Ingal👆.

In other words, the words like You, He, She, and the many other words associated with them, which define a person languishing at the bottom socially or economically, are the same in English as those associated with a person of higher standing.

However, in feudal languages, the words like You, He, She, and the many other words associated with a person of lower status are inherently inferior. There are even clear angles to the invisible links that connect such a person to one of higher standing.

When elevating such a person, what happens is that the individual is raised from one rung on the ladder of ഇഞ്ഞി👇 - ഇങ്ങൾ👆 to a higher rung.

Words like lowest you and lowest he undergo a shift in position.

Many individuals who previously saw this person as stature-neutral You will now find themselves relegated to being addressed as lowest you from the perspective of this person’s new status. This is not something they can easily tolerate.

If a person of high standing elevates a lower individual to stand as their equal, it creates an opportunity for someone previously addressed as highest you or highest him to be addressed as lowest you.

This kind of folly has been committed only by the English in this world.

If an opportunity is given to address someone previously called highest him as lowest you, it does not foster great respect, gratitude, or affection in that person. Instead, it breeds intense resentment, hatred, and a thirst for revenge. Memories of being demeaned by this person or their kin in the past will fester in their mind.

When opportunities are provided for a person at the bottom to improve, their position in linguistic terms, as well as that of their kin, shifts. From then on, they view those who helped them and their kin from the perspective of their new linguistic position. In other words, the person after receiving help is not the same as the person before.

Many forms of subservience in them may vanish.

While they might display subservience towards the person who helped them for a short time, this change in them becomes a significant source of discomfort for others. This is because, in their minds, the person they had placed in a certain position has disappeared.

This person now appears in a different position. Maintaining them in this new position requires a tremendous struggle in linguistic terms.

The English have positioned many ethnic groups across the world as their equals in linguistic terms. This includes continental Europeans, black Africans, people from the Far East, Asians, South Asians, and others.

However, even though all these groups stand as equals to the English in the English language, it is often understood that many among the English have felt some invisible difference persisting among them. Yet, they lack any knowledge from their studies in thermodynamics, chemistry, biology, political science, or social sciences to understand what this difference is. The only insight they gain is that some form of racial conservatism exists within them.

Pointing to this as a flaw in the study of thermodynamics, chemistry, biology, political science, or social sciences is possible. However, if this is mentioned now, the reader may not accept it. We can revisit this later.

If a person is shifted, either through linguistic terms or environmental influence (ambiance), from one rung on the ladder of Inhi👇 - Ingal👆 to a higher rung, it is likely to bring about significant mental exhilaration in them.

Conversely, if the same person is shifted, either through linguistic terms or environmental influence (ambiance), from one rung on the ladder of Inhi👇 - Ingal👆 to a lower rung, it is highly likely to cause significant mental distress. They may behave erratically or even become violent.

Often, they may not attack the person who demeaned them linguistically but instead target someone else within the system that facilitated this situation.

English is a language that allows for simple communication and interaction with people of varying statuses in a workplace setting. However, even in this language, it is not possible to interact without noticing status differences entirely. This is not a flaw in the language but rather a reality created by the existence of different positions in the workplace.

However, during social communication, factors such as a person’s workplace, job position, age, or their parents’ job position do not affect the interaction.

In feudal languages, however, when engaging in such communication, as long as details like workplace, job position, age, or parents’ job position are concealed, there are no significant issues. But if one person in the group reveals their job position, the tone and form of the words used by many in the conversation will change.

This also affects the social fabric of South Asia.

If there are any further corrections, additional text, or clarifications needed, please let me know, and I’ll address them promptly. Thank you for your patience!

9. To purify the wicked

The next in the scattered thoughts lingering in the mind.

In feudal languages, the distinction between the exalted and the lowly exists everywhere. Yet, this is rarely seen as a significant issue. For it is an eternal truth and an immovable reality in society, like an unyielding rock.

It is only after becoming accustomed to English, a language with flat codes, that one realises this reality does not exist in English.

Some who have gained this mental awareness in English have experienced a bitter lesson when attempting to apply the same social and personal relational links they experienced in English to a feudal language.

Imagine a great capitalist addressing both his highest-ranking officer and the person who sweeps his office as lowest you.

From a quick glance through the lens of English, both these subordinates appear to show subservience to the great capitalist and address him as highest him. Thus, it might seem that both subordinates stand on equal footing with each other.

But that is not the reality. In the intangible reality of the ladder of Inhi👇 - Ingal👆, which is hard to grasp in English, these two groups stand at vastly different levels.

The great capitalist offers a seat to his high-ranking officer. But he never offers a seat to the person who sweeps.

However, a great capitalist accustomed to the English language offers a seat to the sweeper as well.

In the intangible reality of the ladder of Inhi👇 - Ingal👆, several rungs explode dramatically, creating a seismic shift in that work environment.

In other words, English is one thing, and Malayalam is another.

In Malayalam, if a person socially held at the bottom is given a chair, a table, or other amenities at an inopportune moment, for the giver to retain the existing respect, they must firmly suppress that person through strict verbal codes.

Otherwise, providing a chair, table, bed, or other amenities to that person will only diminish their respect and gratitude towards the giver.

These matters are part of a point discussed in the previous writing.

In connection with this, I recall a conversation I had. Long ago, there was a company under English ownership. Today, its owners are a South Asian family.

They brought about a social reform in this company.

In the past, an English language atmosphere prevailed in this company. Today, the English elements have been erased, replaced by a Tamil language atmosphere. That was one social reform.

The second was an even more spirited reform.

During the time of English ownership, high-ranking officers and lower employees had separate canteens for meals. But today, people of all levels eat in the same canteen.

The person working there today described this with great emotional fervour.

But I asked a question.

In this canteen, don’t the high-ranking officers address the lower individuals as lowest you, while the lower individuals address the high-ranking officers as highest him? That was my question.

The person who heard the question was taken aback. They had never known anyone to ask such a foolish question.

Yet, today, every movement in India aiming to bring about social reform would falter at this question. Driving out English, replacing it with grand air-conditioned rooms and other amenities, will not bring social reform to human minds or relationships.

Now, another matter.

English does not distinguish individuals based on age, job position, social status, economic level, or family standing in its verbal codes.

Thus, in feudal languages like Malayalam, it is a daily amusement to separate individuals with distinctions such as one friend being a doctor addressed as highest he, while the other, a mason, addressed as lowest he; or one being a teacher addressed as highest he, while the other, a student at that school, addressed as lowest he; or her being the daughter of highest him, and so on. No one sees any significant malevolence in this.

However, in English (and it seems in Arabic too), such a process of separation does not exist. Father, mother, son, and daughter all live within the same level of He and She verbal codes.

It is only when a feudal language speaker gets the chance to refer to these people that they realise, as an epiphany, that such a problem exists in the world.

There is another aspect to this.

A great person and their son—highest he and lowest he.

A lowly person and their son—lowest he and lowest he.

However, in the past, when lowly people looked at great people, they had to maintain the great person and their son as highest he and highest he.

This is the verbal elevation that great people absolutely require. If lowly people attempt to disrupt this by not granting it, they risk having their limbs broken. The great ones knew that maintaining this terrifying fear was the only way to prevent the lowly from disrupting them.

The public sees both an IPS officer and a police constable as highest he and highest he. For if they were referred to as highest he and lowest he, the police constables would be roused with resentment to thrash those who did so.

However, blaming individuals for such matters is futile. The culprit is the feudal language itself, with its malevolent nature and software virus-like environment.

If this language is replaced with the high-quality English, a great mental elevation will naturally arise in these wicked individuals. The wicked will become virtuous.

The physical sciences have no knowledge of such matters. Yet, there is no lack of claim that the final word on the reality of the universe lies with these sciences.

10. On learning multiple languages

It cannot be said that the facial expressions of lowly people have a deformity. For, on the ladder of Inhi👇 - Ingal👆, both the exalted and the lowly may stand on the same rung.

However, among those on the same rung, those who fall to the lower end may exhibit a sense of being mentally and physically suppressed. This may apply to people on every rung.

Some of those who are thus suppressed strive to break free from this oppression through mental exuberance, clamour, boisterousness, or loud merriment.

Such individuals can be quickly identified when driving a vehicle. Loud honking, intense competitiveness, and discourteous driving towards other drivers can be seen as identifying markers.

This phenomenon is absent in English.

Another thought lingering in the mind is about learning multiple languages. Today, on social media, one occasionally encounters individuals claiming to know many languages.

It is almost 100 percent certain that the human brain operates through a brain software. This brain software not only shapes social structures, human thoughts, and emotions but also designs the physical universe for the human mind.

Language, as a tool for communication, is itself a part of this brain software. However, language encompasses more than just communication coding. It likely influences and controls the brain software’s functioning, behaviour, character, and disposition.

In most living beings, similar communication systems and other mechanisms can be observed. These systems may encode various social structures.

For example, a colony of ants has a specific communication system and language, along with a prescribed social hierarchy and order. The ant colony lives and interacts according to this system.

However, if another language system is introduced into this ant colony, the existing social discipline might become chaotic. Alternatively, individuals in the colony may diverge into groups with different behaviours and social disciplines.

The same applies to humans.

In a region where only Tamil is spoken, if the Malayalam language spreads, minor changes may occur in the social structure.

However, since Malayalam and Tamil share similar hierarchical tendencies, no significant social division would occur.

But if English, a language untainted by any hierarchical degradation, spreads among these people, a significant division would indeed occur in that society.

Those who know English would appear distinctly different. The subservience and deference seen in Tamils would not be found in them.

Now, consider what follows.

If an individual learns multiple South Asian languages like Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu, Hindi, Kannada, Oriya, or Marathi, minor variations in behaviour might emerge in their brain software.

However, since all these languages share similar traits of subservience, inferiority, and dominance, no significant opposing tendencies would necessarily arise in the individual’s brain software.

But if the same individual learns English in its pristine, unadulterated form and uses it for thinking, imagining, and behaving, a distinctly different personality would visibly emerge in them.

In other words, learning multiple languages within the Indian subcontinent does not lead to a dual or conflicting personality in an individual.

However, if English is learned at its highest level alongside South Asian languages, the likelihood of a dual or conflicting personality emerging in the individual is very high.

This is, in fact, a mental disorder by the definitions of the foolish science of psychology.

For the purpose of this writing, the brain can be imagined as a computer. Computers have something called an Operating System, such as Windows 8, Windows 10, or Windows 11.

The different Operating Systems mentioned here have minor differences. They can collectively be referred to as Microsoft Windows.

However, Linux and macOS are entirely different Operating Systems. Typically, no one installs multiple Operating Systems on the same computer, as there is no need for it.

Moreover, installing different Operating Systems on the same computer may cause them to operate incompatibly. Still, some people do install multiple Operating Systems on a single computer.

For most people, this is an unnecessary endeavour.

The same applies to learning multiple distinct languages. In reality, it is better for others and the individual if a human brain with English installed does not have another language installed.

Similarly, if a human brain with Indian languages installed also has English installed, to fully benefit from the English language software, the Indian languages must be uninstalled from that brain.

Understand this: one software has characteristics opposite to the other.

11. The condition of releasing toxic fumes

Around 1989, I first wrote extensively in English about the phenomenon of feudal language. Various efforts from multiple platforms were made to prevent that writing from reaching the public eye. I won’t delve into that now.

However, around 2002, I published a lengthy book online titled March of the Evil Empires: English versus the Feudal Languages. With that, the term feudal language began appearing in Google Search and other platforms. Initially, these searches pointed to my book and other writings.

But soon after, a system emerged in these search engines that began diverting online searchers elsewhere.

There are many things to say about this, but I cannot go into them now.

Another phenomenon emerged. Some individuals assigned a completely different meaning to the term feudal language—one entirely unrelated to what I intended—and began promoting it on online platforms.

Today, if you search for feudal language on Google’s Bard.ai (https://bard.google.com/), you’ll find a definition that has no connection whatsoever to the meaning I described in my writing.

It claims that feudal language refers to the social hierarchy and structure that existed in continental European societies long ago. It even lists words as examples of feudal language:

Vassal, Lord, Knight, Castle

Manor, Serf, Peasant, Tenant

Rent, Fief, Homage, Fealty

Surrender, Ransom, Crusade

Tournament, Joust, Heraldry

If this definition were translated into Malayalam, feudal language would be defined by listing words like:

King, Queen, Steward, Nair overlord, Police Sub-Inspector, Doctor, Commoner, Maid, Slave, Lorry Driver, Arrest, Obeisance, Salutation, and so on.

However, feudal language is none of these. These words represent social positions or behaviours. Behind them, certain languages operate, some of which are feudal languages. These words themselves are not feudal languages.

In society, when people in various job positions, with different age gaps in personal relationships, or with varying economic capabilities interact or refer to each other, the address term You and reference terms like He and She have different levels in many languages.

For example, in Malayalam, the word You exists in various levels: lowest you, stature-neutral you, you-sir, you-madam, highest you, and so on.

Languages with such word forms are called feudal languages. These word forms are not synonyms. Each has a distinct social or relational positioning, and they cannot be used interchangeably.

To illustrate the different human experiences provided by feudal languages and English, let’s take the word slavery.

In English, this word is Slavery.

In an English social environment, the experience of Slavery for black people was akin to receiving the refined gentleness of the English language atmosphere from the lowest rung of the Inhi👇 - Ingal ladder in African regional languages. In other words, a person who was lowest you under many rungs became stature-neutral You.

However, in South Asian languages, slavery meant dragging vibrant communities down to the lowest rung of the Inhi👇 - Ingal ladder of local feudal languages.

In other words, a person who was you-sir became lowest you.

This distinct human experience was not enabled by two different words—slavery and Slavery. Rather, it was the languages encompassing them.

South Asian employees at companies like Google and Microsoft, along with some continental Europeans, have strenuously worked to conceal the existence of the feudal language phenomenon from public attention. Some may have directly participated in this.

However, the owners of these companies or all their employees may not be aware of such conspiracies.

This itself is a feudal language phenomenon.

In any organisation operating in feudal languages, there are personal relationship links that often go unnoticed. These are often invisible networks created by word-based relationships like lowest you, highest him, elder brother, elder sister, lowest he, highest he, and so on.

Within these networks, various information, discussions, secret stories, or activities with specific intentions may exist. Each word-code route may hold specific secrets and conspiracies.

Those not entangled in these word-based relationship links will have no connection to or awareness of the activities within these invisible networks. Yet, these covert activities occur right beside them.

At the same time, such secretive personal relationship networks do not exist in English platforms without deliberate planning. This is because, in English, personal relationship links do not move through corridors formed by word-built walls.

Bard.ai concludes about feudal language as follows:

In other words, it claims that feudal language is a social structure that existed in Europe long ago.

But the reality is different. The many hardships experienced by people in countries like India today are directly caused by these languages. Feudal languages are an invisible, terrifying entity that profoundly and adversely affects the human mind and personality.

For South Asians and continental Europeans working in English-speaking nations, the spread of such information in those countries could be problematic.

However, concealing this malevolent truth does not seem beneficial. Hiding such information is akin to opening the lid of a bottle filled with toxic fumes.

In 2011, I filed a writ petition in the Kerala High Court, arguing that Malayalam is a harsh feudal language and should not, under any circumstances, be made the language of education, administration, or judicial proceedings. Granting statutory validity to this malevolent language would divide the state’s citizens into at least three distinct levels.

There was a deliberate behind-the-scenes plan to turn this writ petition into a mockery and have the High Court Chief Justice publicly dismiss it in court.

However, when the Chief Justice heard the arguments, took the matter seriously, and accepted the writ petition, every effort was made behind the scenes to ensure no media outlet reported it.

At the time, I was grappling with various personal issues and could only experience these events firsthand.

It was also a fact that many academics and high-ranking officials from Kerala had family members working in global online platforms.

Some in critical positions made significant efforts to conceal the topic of feudal language. I experienced this directly on international online platforms at the time.

The inspiration to write about these matters now came from seeing recent accounts by individuals who retired from companies like Google, sharing their work experiences.

They enjoyed an extraordinary work environment, unlike anything found in local Indian companies.

However, what they all fail to mention is that they worked in a remarkable platform sustained by an English language atmosphere.

None of them seem interested in acknowledging the historical significance of English, and thus England. Many believe the exceptional work experiences they had were due to some great mental skill or superiority within themselves.

If the language atmosphere within Google had shifted to Malayalam, Tamil, Hindi, or Telugu, that work environment would have been poisoned. However, in the US and other English-speaking nations, where an English language social atmosphere prevails, it would take time for this toxic spread to take hold.

12. The spider web of language and the train accident

This is not what I intended to write about now—that is, the railway accident that occurred two days ago.

The Archaeological Department might claim, through observational studies, that trains existed in India 30,000 years ago and that they have discovered the rail tracks on which they ran.

However, the railway system in India today was inherited from British-India.

This began in British-India in the 1830s, known as the Indian Railway.

In British-Malabar, there were Indian Railway stations, and trains operated.

Although it can be said that there were no trains in Travancore, a metre-gauge railway line to Madras via Aryankavu (through a mountain pass) had been established by 1904.

This likely provided the Travancore royal family with a shortcut to Madras. In Madras, royal family members could walk the streets freely. In Travancore, they led confined lives within palace walls.

For many lowly individuals, this route may have been a path to escape to British-India.

What I meant to discuss is something else.

The Indian Railways, or British-Indian Railway, was, as I understand, an institution operated through an English communication system. Therefore, those working within it likely communicated in English.

Many Anglo-Indians seem to have been a significant asset in this institution.

Those working in it earned modest salaries but maintained great personal charisma.

Things changed in the India born in 1947.

The internal communication language of the railway itself changed. The flat-natured English was wiped out, and the railway system shifted to Hindi, the common language of India’s lowest communities.

Official salaries soared to the skies.

Around the 1980s, the fading English and the rising Hindi seem to have clashed fiercely within the railway system. Trains began to run late.

I recall trains being delayed by 24 hours or more.

However, Hindi gradually drove out English. With that, the railway system regained great efficiency.

The highest you - lowest you (Ingal - Inhi) personal relationship created a military-like discipline.

The advantage of this military discipline is that the machine operates on predetermined paths without any deviation.

This efficiency persists in all platforms where the superior person is highest you and the subordinate is lowest you.

However, in such mechanical systems, clearly identifiable highest you and lowest you individuals must occupy each position. If a person of the same mental calibre is absent in the lowest you position, the system may stall or operate erratically.

Even a trivial instruction may fail to be executed.

Moreover, at critical moments or in dangerous situations, individuals wait for clear instructions from above. They lack the courage to make decisions or take action independently.

This is because such actions would be perceived by the language’s verbal codes as a challenge to those above.

This has genuinely affected historical events in many South Asian regions.

QUOTE from Malabar Manual:

Tippu had, unfortunately for himself, by his insolent letters to the Nizam in 1784 after the conclusion of peace with the English at Mangalore, shown that he contemplated the early subjugation of the Nizam himself.

It seems that Tippu Sultan used lowest you instead of highest you when addressing the Nizam of Carnatic in his letters. Tippu may have believed he was now the emperor.

This was a customary act in ancient times when a king became an emperor. Some historical events related to this could be mentioned, but I won’t go into them now.

Defeating Tippu Sultan likely became a personal necessity for the Nizam.

Similarly, when Tippu Sultan clashed with the English Company’s army near Palghat, the linguistic barriers within the Mysorean army became a significant liability, as I discerned from the Malabar Manual.

but from an official neglect to send the order to a picquet of 150 men stationed at, the extraordinary distance of three miles, five hours were lost

This cannot be understood from England.

The fools in England might think the English rule spread worldwide solely due to the English’s great courage and valour.

In those days, Brahmins in South Asia acted as messengers. They were generally not attacked. No one obstructed their path. Moreover, they received lodging and food at Brahminic temples wherever they went.

However, they carried messages only for the exalted.

In other words, the social and linguistic status of the sender, the messenger, and the recipient was a key factor in the messaging process.

In such a malevolent region, the English East India Company established a postal department that could deliver letters even from a low-caste person.

Returning to the point.

Every organization has a pace at which things normally proceed. For example, imagine ten tasks per hour.

At this pace, efficiency issues don’t arise. A slow-moving vehicle straying one foot or ten feet off the path causes no trouble.

But in wartime conditions, tasks move at a frenetic pace—say, ten tasks per minute.

The density of actions in time increases drastically.

On a highway with vehicles speeding at 100 km/h, a vehicle drifting an inch off could cause a massive accident.

The shift from a scenario where straying ten feet is harmless to one requiring 100 km/h speed is a moment of high action density.

When soldiers are idle, whether instructions are followed or not matters little. But during a war, a small error can lead to disaster.

This is where the difference between English and feudal language systems becomes evident.

Feudal language organizations form a spider web of highest you - lowest you word-based relationships.

If action density surges unexpectedly in wartime conditions, and clear highest you - lowest you personalities are absent in each position, instructions won’t move forward.

Ideas and directives wander, seeking the right person to carry them. They don’t progress. Instructions fail to reach their destination on time.

This is a moment of high action density.

Events rush forward like a speeding train, leading to catastrophe.

Where a single word could ensure vast efficiency, a major disaster strikes.

If investigated thoroughly, the initial cause of the train accident in Odisha could likely be traced to language code errors.

This is because highest you - lowest you positions may be occupied by individuals under immense economic, social, familial, or other pressures, either suppressed or elevated.

Such words can stir intense emotions. Normally, railway operations have controls to restrain such emotional outbursts.

However, immediately after the first accident, the failure to efficiently manage other trains rushing to the same spot was where rational directives faltered, lost in confusion over who should send, carry, or receive messages.

This problem has now crept into English-speaking nations and institutions.

Feudal language speakers work in groups across various platforms in English-speaking countries today. English speakers can only see their English behaviour. They cannot see the personal relationship threads moving through feudal language words or the intricate webs of relationships within them.

Another issue with Indian Railways is the roster system of reservation.

This sows explosive seeds in the highest you - lowest you obedience-authority chain. A low-caste person entering as a junior officer quickly ascends to exalted positions.

In other words, a lowest you becomes a highest you, and a highest you becomes a lowest you.

I don’t know the full picture here.

But at critical moments, when directives must flash forward at lightning speed, these chains break.

Passengers on trains are unaware of this. The journey they enjoy is a marvel established in the 1800s by English East India Company officials in this subcontinent.

Today’s Indian officials, filmmakers, media workers, and academics call those English individuals thieves. They shed crocodile tears over human suffering in disasters, relishing the misery.

13. Into the backstory of mental disorders

The English administration in South Asia undertook various efforts to understand the social environment and ethnic groups. In the early days, the diverse communities of South Asia were as incomprehensible to them as many other living creatures.

One of the initiatives related to this was conducting a Census every ten years. These censuses recorded individuals’ characteristics, occupational skills, dependencies, shortcomings, and more, providing a comprehensive review of each aspect.

While quickly reading through Castes and Tribes of Southern India, Volume 2 by Edgar Thurston years ago, the following sentences caught my attention:

Writing concerning the prevalence of insanity in different classes, the Census Commissioner, 1891, states that “it appears from the statistics that insanity is far more prevalent among the Eurasians than among any other class..........”.

The subject seems to be one worthy of further study by those competent to deal with it.

This is genuinely connected to the terrifying ability of feudal languages to induce mental disturbances. Studying this requires a deep understanding of the various characteristics and traits of feudal languages, which cannot be gained from any academic study today.

Back then, Eurasians referred to individuals born to European men and local South Asian women.

It can be assumed that many of these individuals were of English-speaking lineage. Such people likely spoke fluent English among their fathers and their associates. This mental state would foster significant mental freedom in them.

In other words, they would possess a mindset unbound by the Inhi👇 - Ingal👆 ladder of local languages. The verbal barriers created by elevated word codes and the mental inferiority induced by lower word codes would not penetrate their minds in this language environment.

However, their mother’s family was often entirely rooted in local languages. Frequently, they belonged to the lower strata of society, standing on one of the lower rungs of the Inhi👇 - Ingal👆 ladder.

To them, this individual would be someone beneath them.

In other words, a person at the level of lowest you, lowest he, or lowest she.

The local community would also attempt to evaluate this individual based on their mother’s family’s status.

This creates a mental phenomenon absent in English.

In English settings, this individual would exhibit a grand personality and a vibrant mental state. In English, this is merely a normal mental standard.

However, when this same individual interacts with their local family or other local people in the local language, they are forcefully pressed down to the lower rungs of the Inhi👇 - Ingal👆 ladder, as if crushed.

The person existing in English is not the one present here.

This creates starkly contrasting personal relationship links through words and interactions with numerous individuals.

The mental impact of this is severe.

Words carry immense power.

If a father addresses his son as lowest you, there’s no issue. But if the son, with great composure, addresses the father as lowest you, the very concept of father in Malayalam would vanish.

If a policeman addresses a commoner as lowest you, it’s not a problem. But if a commoner addresses a policeman as lowest you, an explosion could occur.

The fact that words possess such power is still unknown to English-speaking nations.

In most parts of South Asia, there exists a latent potential for violent outbursts at any moment. Often, this remains a mere shadow, not erupting. This is because various silent precautions exist within institutions to prevent such outbursts.